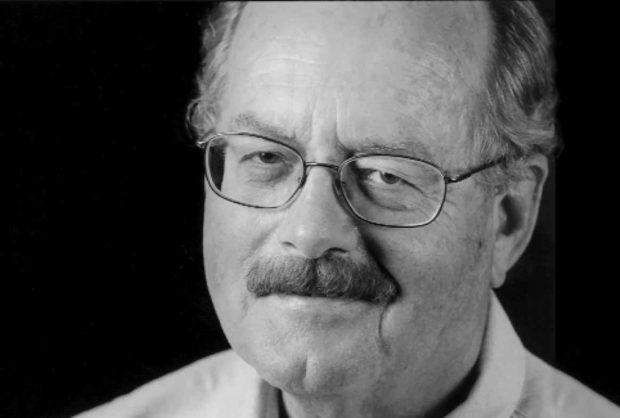

William Wirtz

Emeritus Professor of Zoology and Biology

1937–2020

William Wirtz, emeritus professor of zoology and biology, died at home on Dec. 24, 2020, after a long illness. He was 83.

Wirtz was born in New Jersey on Aug. 16, 1937. He attended Rutgers University, where he studied ecology under one of the nation’s foremost experts, graduating in 1959. At Cornell University, he did his postdoctoral research on the habits of the Polynesian rat in the leeward Hawaiian Islands. He received his Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology in 1968. He joined Pomona College the same year in September, teaching until his retirement in 2003.

As a child, Wirtz enjoyed wandering the woods and taking a boat to the nearby salt marsh to study the wildlife. “I was the kid who brought home mice and snakes. And I never stopped,” he told the Pomona College Magazine in 2003 interview.

At Pomona, Wirtz was responsible for establishing, maintaining and upgrading Pomona’s animal care facility and program. He was also known for his two 10-foot snakes, a reticulated python and a boa, which on at least two occasions over the years had escaped the classroom. (Both snakes were found shortly after their escapes, and eventually were both rehomed to wildlife centers).

Professor of Biology and Neuroscience Rachel Levin remembers Wirtz as an institution within Pomona’s Biology Department. “He was totally at home in the wilderness and he was a skilled and passionate naturalist,” she says. “He had a way of engaging students and turning them on to natural world … He took many generations of Pomona students on unforgettable adventures to Pitt Ranch and the Granite Mountains.”

One of those students, Audrey Mayer ’94, now a professor of ecology and environmental policy at Michigan Technological University, credits Wirtz for launching her career. “I knew I liked biology, but I had no idea what to do after in terms of a career. He’s the one who encouraged me to get a Ph.D., which was not on my radar at all. I have a book coming out in March on the gnatcatcher—that was a book that started with him.”

Julie Hagelin ’92, now a senior research scientist for the Institute of Arctic Biology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, says Wirtz was the first person who made her realize she could do field biology. She learned the step-by-step process of handling small mammals on her first day working as his student assistant—a skill she took with her to graduate school. “It was like he opened a door to a secret world of biology: in the bushes and brush, with these little animals that are only active at night.”

Retired doctor Sharon Booth ’78 shares the same feeling. “Wirtz’s ecology 101 course awakened my eyes to the natural world and the joy of learning about its complexities.” Booth went on to work for Wirtz, spending at least one summer in the chaparral trapping rodents for population surveys.

Joel Brown ’80, now an emeritus professor of biological sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago, was also one of Wirtz’s early protégés. “I’d always loved ecology, had always loved nature, but had no idea that extending one’s love for nature could be a career.”

“Bill was a nonstop documentary and encyclopedia who taught us all these techniques, and can you believe it, we were being paid!” Brown became a student worker for Wirtz and learned how to trap small animals, put radio collars on raccoons and coyotes, band red-tailed hawks and noose lizards. “It was completely transformative. I went home and told my folks I finally knew what I wanted to do. I want to be an ecologist. And so, from that day forward, Bill offered me amazing opportunities.”

“He was an outdoors guy, a classic mud-and-boots ecologist,” says Brown. “Bill Wirtz was one of the foundational mentors in my life; without him, all the other sequences of my life would not have happened.”

Wirtz was a longtime member of the Mt. Baldy Volunteer Fire Department and lived in the mountains with his wife, Helen, for many years. In the 1980s, he studied habits of coyotes who scavenged in the foothills of Claremont and Glendora, even adopting a rescued coyote. He did extensive work on the distribution of rodent populations in the San Dimas Experimental Forest and studied the nesting habits of the endangered California gnatcatcher that lives in endangered coastal sage scrub. These were just some of his many field research interests over the decades.

After retiring from Pomona in 2003, Wirtz and his wife became involved in equine rescue, including rescuing horses during fires, and served on the board of the Inland Valley Humane Society for some time. He also became more involved in one of his favorite hobbies: Civil War reenactments.

Wirtz leaves behind a large legacy of Pomona ecologists and biologists. “There’s a lot of us around who got that start in our careers working for him,” says Mayer.

Wirtz is survived by his wife, Helen, and a son, William.

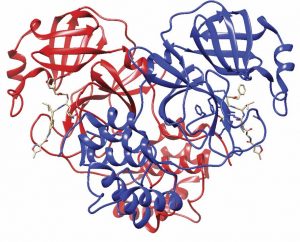

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX.

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX.

GATHERED ON THE pitcher’s mound during class, Pomona College students feed balls into a pitching machine, then quickly glance down at an iPad.

GATHERED ON THE pitcher’s mound during class, Pomona College students feed balls into a pitching machine, then quickly glance down at an iPad. CASH. BABY. BOOM. Stocks with clever ticker symbols such as these continue to outperform the market as a whole, a new study has confirmed.

CASH. BABY. BOOM. Stocks with clever ticker symbols such as these continue to outperform the market as a whole, a new study has confirmed.

The 2019 recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on Pomona faculty, were (from left):

The 2019 recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on Pomona faculty, were (from left):