Onetta Brooks ’74

Lives in: She is in Fairfax, Va., through May serving as an interim pastor. Education: B.A., mathematics, Pomona College; master of public administration, Cal State Dominguez; master of divinity, San Francisco Theological Seminary/Southern California.

Career: Ordained in 2007 in the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) and is serving as the interim pastor of MCC of Northern Virginia. She worked for 34 years as program manager/systems engineer/software engineer/programmer analyst at aerospace and defense companies such as Rockwell, Hughes, Logicon and Northrop Grumman.

Alumni involvement: Served on the Alumni Council from 1986 to 1989; after she was inducted into the Pomona–Pitzer Athletic Hall of Fame (volleyball and basketball) in 1984, she served on the Athletic Hall of Fame Committee for several years; supported and participated in activities of the Office of Black Student Affairs over the years; participated in a few alumni phone-a-thons.

Community involvement: Brooks serves on the MCC Governing Board through 2016 and supports various social justice groups in the Los Angeles and in the D.C. metro/Fairfax County areas.

Adam Conner-Simons ’08

Lives in: Cambridge, Mass.

Education: Conner-Simons majored in psychology. He was part of the campus band the Fuzz, was involved in The Student Life newspaper and the gender-discussion group Male Dissent and served as a student representative for the Admissions Committee.

Career: As a student, Conner-Simons did research for Psychology Professor Patricia Smiley, and worked at the Career Development Office and the Office of Communications. He is communications coordinator at Brandeis International Business School at Brandeis University.

Alumni involvement: Conner-Simons writes regularly for Pomona College Magazine, and has helped organize Boston-area alumni events and served as an alumni ad- missions interviewer.

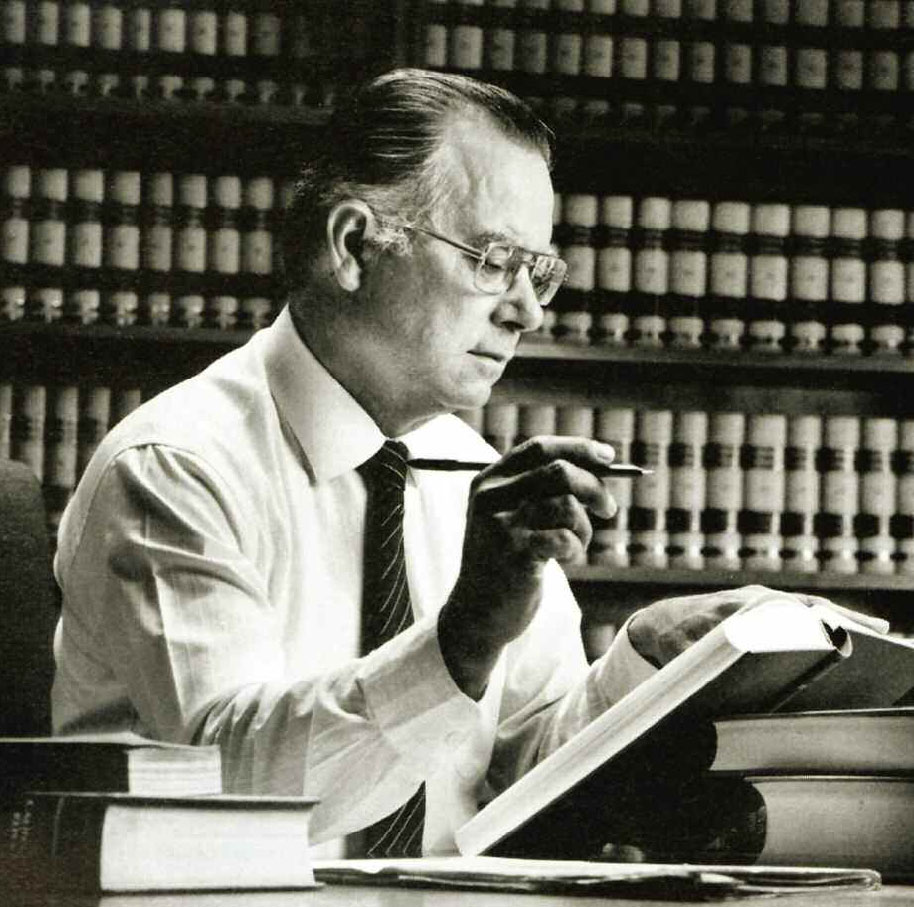

Bill Ireland ’81

Lives in: Venice Beach, Calif. Education: Ireland majored in history, before attending UCLA Law School. He played water polo and swam at Pomona and is in the Athletic Hall of Fame. He met his wife, Ellen Brand Ireland ’82, when he was visiting her roommate, Caren Carlisle Hare ’82, who was a freshman swimmer.

Career: Ireland is a partner, specializing in commercial litigation, at Haight Brown and Bonesteel, a Los Angeles-based law firm. One of the cases he worked on re- sulted in two published books, Greenmail by Norma Zager and Parts Per Million by Joy Horowitz. Ireland competes in open water swimming competitions, which is mostly an excuse for trips to places with warm water.

Alumni involvement: Ireland was on the Alumni Council from 1987 to 1996. After working with events, and volunteering for the 90th and 100th anniversary celebrations, he was president of the Alumni Association for 1993-1994. Later, Ireland served as an alumni volunteer on the Board of Trustees Nominating Committee. Ellen and he have both repeatedly chaired their class reunions. Bill was also an Alumni Admissions volunteer. Community involvement: Bill and Ellen have been involved with their local Presbyterian church. Bill has been a trustee, and an elder, as well as clerk of the Presbytery Judicial Commission for the Presbytery of the Pacific. Bill also has been an officer and board member for the governing board and the foundation for Ghost Ranch, a Presbyterian camp and conference center in Abiquiu, N.M.

Kayla McCulley ’09

Lives in: Amherst, Mass.

Education: A Pomona double major in international relations and French, McCulley is working toward her M.B.A. and master’s in sport management at the University of Massachusetts. At Pomona, McCulley was a four-year member and senior co-captain of the lacrosse team and was active with the European Union Center of California.

Career: After graduation McCulley departed for Europe, first to Brussels as an intern with the U.S. Mission to NATO and then to Switzerland as a Fulbright scholar. Since then, McCulley has pursued her passion for sports with positions at the National Collegiate Athletic Association, Octagon and the Ivy Sports Symposium. She is a frequent contributor to national media outlets such as espnW, Women Talk Sports and The Business of College Sports.

Alumni involvement: McCulley serves as an alumni admissions volunteer in the liberal arts college hotbed that is Western Massachusetts, enticing would-be Williams/Amherst/Mount Holyoke students to head west and become proud Sagehens.

Susanne wanted those things, too. At Pomona, she embraced the life of the mind, engaging in those deep late-night conversations, and finding “just the right mix of serious study and social life.” She was an English major—Phi Beta Kappa and Mortar Board—who had many friends in the sciences. She served as arts and culture editor for The Student Life, and also took modern dance classes from Professor Jeannette Hypes, performing several times in her dance troupe. She soaked up everything she could from the small liberal arts college atmosphere.

Susanne wanted those things, too. At Pomona, she embraced the life of the mind, engaging in those deep late-night conversations, and finding “just the right mix of serious study and social life.” She was an English major—Phi Beta Kappa and Mortar Board—who had many friends in the sciences. She served as arts and culture editor for The Student Life, and also took modern dance classes from Professor Jeannette Hypes, performing several times in her dance troupe. She soaked up everything she could from the small liberal arts college atmosphere. When Karen Gerstenberger ’81 holds a quilt in her hands, she sees more than red and purple and blue and more than crisscross lines of thread. She sees the patterns that grief can make on the lives of patients and families. She imagines a young face, cradling the blanket they may receive on their first day of cancer treatment at a Seattle hospital.

When Karen Gerstenberger ’81 holds a quilt in her hands, she sees more than red and purple and blue and more than crisscross lines of thread. She sees the patterns that grief can make on the lives of patients and families. She imagines a young face, cradling the blanket they may receive on their first day of cancer treatment at a Seattle hospital.