Cameron Blevins ’08 photographed by Flor Blake

On an 80-degree September day in 2016, Cameron Blevins ’08 was wearing a sweater as he waited in one of his favorite places in the world.

The windowless Ahmanson Reading Room of the Munger Research Center at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, is a carpeted kingdom of quiet. It is kept chilly to safeguard the more than 450,000 rare books and 8 million manuscript items the library holds.

Blevins, now a professor of U.S. history and digital humanities at the University of Colorado Denver, handed an archivist a little slip of paper containing his request for documents. He was deep into research for what would become Paper Trails: The US Post and the Making of the American West, exploring how the postal service, working with private entrepreneurs, played a central role in extending the federal government’s reach to the Pacific.

A Wall Street Journal reviewer will go on to call the book “a wonderful example of digital history built on information technology and archival research.” First, though, came the search.

A Wall Street Journal reviewer will go on to call the book “a wonderful example of digital history built on information technology and archival research.” First, though, came the search.

Five, 10, 15 minutes went by before a trolley rolled toward Blevins bearing archival boxes filled with letters from the 1850s through the 1890s.

“You feel like a kid in a candy store,” he says. “The archives are where you find little windows into the past. You look through the catalog to try to find things you can metaphorically unwrap. It’s magical.”

Blevins originally came west from New London, Connecticut, to attend Pomona. In his first semester, his life changed when he wowed Professor of History Sam Yamashita with his paper about major league baseball players’ barnstorming tour of 1930s Japan. “He found it fascinating,” Blevins recalls. “I remember him saying, ‘If you wanted to, you could do this as a career.’ I hadn’t thought until then that this was something I could do for a living. It got my wheels turning.”

Thanks to a Pomona research grant, his sophomore summer he mastered GIS (geographic information system) software and used it to map the landholdings of Venture Smith, an enslaved man who bought his freedom in colonial Connecticut. “This was absolutely transformative for me in my career,” says Blevins, who earned his Ph.D. in history from Stanford. “Pomona supported my research and gave me the independence to spend a summer digging in archives and learning this technology. I’m not sure I would’ve had the same career trajectory if I hadn’t had this experience. It opened my eyes to the potential of technology to study the past and propelled me down this road toward the digital humanities.”

The realm of computational analysis and data visualization offered Blevins a new way to bring history to life. It didn’t replace—and still depended on—the time-intensive work of archival research at places like the Huntington, sifting through box after box of dead-end materials penned in indecipherable script to find the few that will matter. He describes that process as a “combination of excitement, hoping and lots of waiting.”

“All historians have an experience where you’re in the archives and come across some document, and a thrill runs through you. Maybe it’s something personalized, individualized—a human being I’ve been thinking about. I’m able to see him in front of me.”

Blevins would experience such a thrill during his research. But first came the wider context.

“History,” says Blevins, “is not some magic bullet to let you predict the future or avoid mistakes, but it is absolutely crucial for understanding the state of the world and society.”

Historians of the Western frontier once told tales of glorious conquest. In his multivolume book The Winning of the West, Theodore Roosevelt, who became president of the American Historical Association a few years after serving as president of the United States, proclaimed it was “our manifest destiny to swallow up the land of all adjoining nations who were too weak to withstand us.”

The pattern of conquest is “pretty dark,” Blevins says. “The history of the United States is based on two inescapable facts—African slavery and the forced dispossession and attempted extermination of Native people. That’s inescapable and a vitally important part of our history,” he adds. “You can’t understand how we got where we are today without coming face to face with those facts. All of us are sitting on plundered land. That is something our nation needs to face.”

Paper Trails tells how an institution as seemingly benign as the post office helped enable the military and settlers to bring destruction to Native Americans. “The American state’s violent campaigns were conducted with envelopes as well as rifles,” writes Blevins.

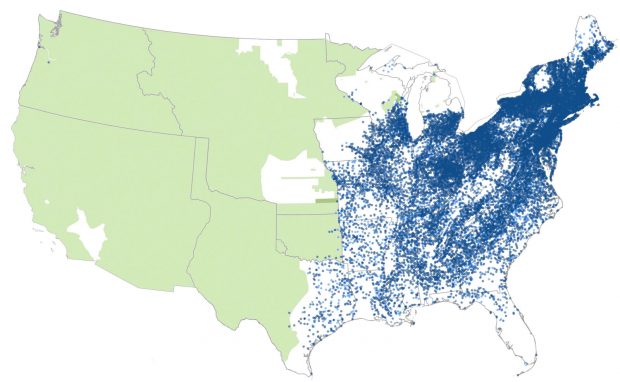

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 opened the floodgates for westward expansion, and the forcible displacement of Native Americans accelerated in the 1830s. The postal system continued the westward march.

USA existing native lands compared to post offices in 1848.![]() US Post Office (exact location)

US Post Office (exact location)![]() US Post Office (approximate location)

US Post Office (approximate location)![]() Native Lands

Native Lands![]() Reservations

Reservations

Between 1848 and 1895, the federal government opened 24,000 post offices in the western United States. By 1889, the U.S. had 59,000 of those offices nationwide and 400,000 miles of mail routes—a system larger than any other nation’s. (Blevins notes that by comparison, there are fewer than 14,000 McDonald’s restaurants in the U.S.)

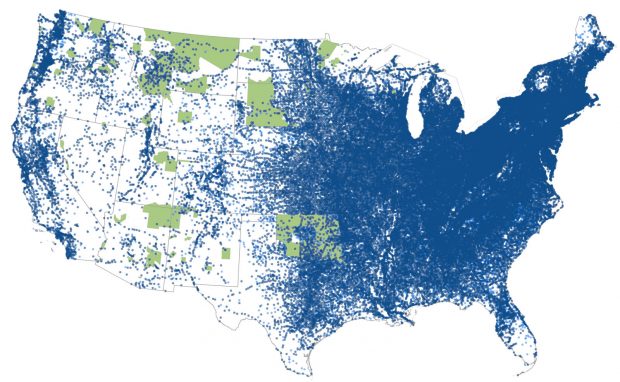

He calls this sprawling, fast-moving system a “gossamer network”—as intricate and ephemeral as a spider’s web—that expanded and shrank with each gust of population movement. Some 48,000 post offices closed, changed names or moved during this unstable period. “What surprised me was the speed with which the network could extend these tendrils into really distant places and then also contract,” says Blevins. “Post offices would sprout up in a mining camp and disappear two years later.”

USA existing native land reservations compared to post offices in 1893.![]() US Post Office (exact location)

US Post Office (exact location)![]() US Post Office (approximate location)

US Post Office (approximate location)![]() Native Lands

Native Lands![]() Reservations

Reservations

The rapid westward growth of post offices was “a subtle, unexpected system” that accelerated settlers’ migration and violent military oppression, Blevins argues. He believes that the post office’s role in hastening westward migration and armed conflict was so ubiquitous that historians failed to see it.

“Again and again, the protection of [mail] transportation corridors provided a pretext for military action,” Blevins writes. One western officer griped, “Except to guard the El Paso Mail I am unable to discover the necessity for a single soldier at this post.”

True to the data visualization work that Blevins began as a student, Paper Trails emerged from the use of digital history and interactive maps and charts. A visit to gossamernetwork.com, the book’s companion website made in collaboration with designer Yan Wu, reveals clusters and sprinklings of hundreds of pink, purple and blue dots that represent remote post offices in places like Skull Valley, Arizona (established 1869, still operating); Spotted Horse, Montana (established 1890, discontinued 1892); and Mud Meadows, Nevada (established 1867, discontinued 1867). With a computer click one can watch them suddenly appear near gold strikes or materialize in lines as straight as railroad tracks.

Run by contractors who filled local needs as they arose, the postal system expanded so rapidly that its Washington overseers could barely track its growth. “The extension of the mail service was unquestionably far in advance of the actual needs of the country. …It is questionable whether the good accomplished in the remote regions of the West compensated for the positive evil which resulted,” Postmaster General Thomas James wrote in 1881, referring to postal service corruption, not wars.

“As humans, we want tidy morality stories with something as a force for good or evil. Of course, it’s never like that,” says Blevins. “What I see as important is less understanding this period in history, but to think about how large networks, systems and structures shape modern life for good or bad.”

He sees striking parallels to today’s tech companies. “We could go into the way something like Facebook amplifies misinformation. But it’s not like people in its headquarters are scheming how to break American democracy,” says Blevins. “It’s that they put things in motion—things they sometimes don’t understand—or they don’t think about the consequences of structures they set up. It’s less about trying to assign individual blame to a company but trying to think about those underlying algorithms that drive misinformation or radicalization.”

There is another side to Blevins’ work beyond analyzing data and systems. They provided powerful insight, but he still had to find the human stories to bring this history of the immense postal system to life. That proved a tougher quest than Blevins expected. “I went into archives expecting 19th-century Americans to be writing about this amazing network and ‘Isn’t it incredible I’m able to communicate with people 3,000 miles away for the cost of a two-cent stamp?’” Instead, he “heard crickets. When things are vast and wrapped into daily life, people don’t talk about them as much as you’d expect.”

But on that day in the Ahmanson Reading Room, after Blevins had pored through box after box of unusable materials, the trolley stopped at his table, delivering one that would yield an entire chapter in Paper Trails.

It contained dozens of letters written from the 1850s to the 1890s by Benjamin Curtis and his sisters Sarah, Delia and Jamie. Orphaned in 1852, they had been sent to live with relatives in Massachusetts, Tennessee, Ohio and Illinois. But thanks to the U.S. Post Office, they stayed in touch, especially when they all moved west to equally remote Wyoming, California, Idaho and Arizona.

It contained dozens of letters written from the 1850s to the 1890s by Benjamin Curtis and his sisters Sarah, Delia and Jamie. Orphaned in 1852, they had been sent to live with relatives in Massachusetts, Tennessee, Ohio and Illinois. But thanks to the U.S. Post Office, they stayed in touch, especially when they all moved west to equally remote Wyoming, California, Idaho and Arizona.

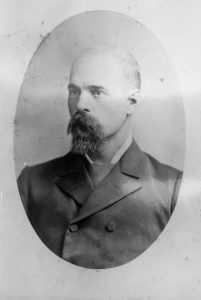

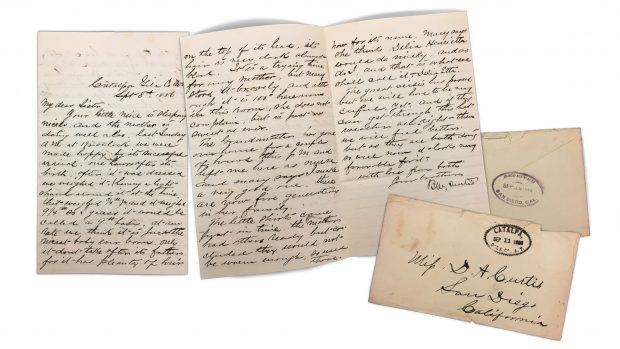

One of Blevins’ favorite letters is from Benjamin to Delia on September 8, 1886. She is in San Diego. He is homesteading in Arizona’s Salt River Valley, east of Phoenix. The nearest town is 30 miles away, but the post office opened a branch two miles from him in Armer and another three miles away in Catalpa. His wife has given birth to a 9-pound baby daughter. “It is a trying time for any mother, and although it is 100 degrees in this room she does not complain,” Benjamin writes and then tells Delia they named the baby after her.

“We think it is just the nicest baby ever born,” he boasts. “Only it don’t take after its father, for it has plenty of hair on top of its head.”

Lo and behold, in the file Blevins found a photograph of Benjamin, who was far balder than the baby. It was a “humanizing moment” for Blevins as he sifted through the letters offering “beautiful, intimate glimpses” into the siblings’ relationships over decades.

Lo and behold, in the file Blevins found a photograph of Benjamin, who was far balder than the baby. It was a “humanizing moment” for Blevins as he sifted through the letters offering “beautiful, intimate glimpses” into the siblings’ relationships over decades.

Although cool-headed computer calculations drive the scholarship behind Paper Trails, the heart of the book beats with human stories. Blevins’ gossamer network of outposts on a map ultimately reveals the vast distances that have always existed in America as well as the ties that bind us together.