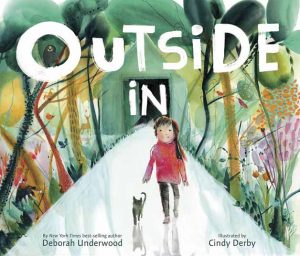

Timing truly is everything, and the children’s book Outside In, by Deborah Underwood ’83, is arguably prescient. Released in April during a pandemic she never anticipated when she wrote the book, it is a vivid meditation on how nature affects us even when we’re stuck indoors. In these strange times of sheltering in place, this book, illustrated by Cindy Derby, gives readers pause to ponder our connectedness to creation.

Timing truly is everything, and the children’s book Outside In, by Deborah Underwood ’83, is arguably prescient. Released in April during a pandemic she never anticipated when she wrote the book, it is a vivid meditation on how nature affects us even when we’re stuck indoors. In these strange times of sheltering in place, this book, illustrated by Cindy Derby, gives readers pause to ponder our connectedness to creation.

Underwood talked to Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham about the world outside, social distancing, maintaining wonder and more.

PCM: Can you tell me a little bit about your relationship to nature, as a child and now as an adult?

Underwood: Well, that’s a really interesting question. We were not a very nature-oriented family. We didn’t go camping and the kind of things that a lot of people do. I remember loving to play in my backyard. I remember going back behind these bushes and digging for treasure. And of course, every time you hit a rock, you’re like, “I’m either in China or it’s a treasure chest.” But it’s funny; it’s been more of a later-life interest for me. I don’t go camping, although I might try that sometime, but I do love being outside. And there’s the botanical garden very close to where I live, and I spend so much time there. That’s really informed my writing and my process. One of the hard things about the pandemic for me was they closed it for a few months. That was a gut punch. It was just horrible. And I realized how much I had depended on being able to walk in that beautiful place and collect my thoughts for writing. So much of picture book writing is thinking, because they’re short manuscripts. It’s 98% thought and 2% getting it on paper.

One of the things that I’ve done over the pandemic is I put a garden into my apartment building backyard. I had no interest in gardening but just the knowledge that this might be the only safe place to go for a while. My landlord had been paying people to come in and chop everything down and spray the yard with Roundup. When I found out they were doing that, I thought, “You know what? If I can at least get some mulch down, maybe they’ll stop putting that toxic stuff all over it.” But then I started putting in plants, and I connected with people on Nextdoor, and neighbors donated pavers and plants, and I went to Home Depot a million times.

The garden has really made me more aware of the nature around me. I’ve always loved animals. I have a bird feeder and I have … Edward and Elinor Pigeon, Elliot and Shadow Pigeon, Buddy the Raccoon who comes and drinks from the hummingbird feeder. All of a sudden, I feel like I have this little wild kingdom.

PCM: Your nonfiction includes so many books about animals and the planet and the universe. What are you trying to communicate to children?

Underwood: Well, interestingly, the nonfiction, that was almost all work-for-hire stuff. I was doing that when I was getting started writing for kids. I made a career change in 2000 when I got laid off from this corporate job that I was not particularly interested in. And I thought, “Well, if I’m going to do something different, this is a good time to make a change.” So, I decided that I wanted to write children’s books. I started doing a lot of research and dipping my toe into that field. But one of the ways that I made money when I was first starting out was doing these work-for-hire books, which traditionally do not pay well at all but are a really good way to learn about the field. And the editor actually assigns the topic. So an educational publisher will say, “We want to do a series about camouflage. We want a book about this, this, this, this. Can you write it?” And you go, “Sure, I can.” But you don’t know anything about the topic. One of my first moments of true panic as a writer was when I’d agreed to write a book about the Northern Lights. And I said, “Oh, yeah, that sounds so cool.” And then I started doing the research and I was like, “I don’t know anything about physics!” And I realized I had agreed to do this book about something that I don’t have the scientific chops to understand completely. But you find good experts who help you and review things, and then it’s like, “OK. I managed to do that.”

PCM: With your fiction, by virtue of writing for children, you’re also writing for adults who read to them, right? What are you trying to communicate to the adults?

Underwood: Honestly, I don’t really think about the adults. I’m not very interested in grown-ups. It’s a strange field because it’s the only one I can think of where the consumer is not purchasing the product. What you have to do is entice the parent enough to buy it for the kid. But most of the time, I’m not thinking about audience at all. I keep saying that I’m essentially a 6-year-old in a grown-up’s body. So if something is interesting or funny to me, I feel it will be to kids. Usually, if you set out saying, “Well, what do I want to try to teach kids?” that’s a fatal error in writing for them. People come up to me and say things like, “Oh, I have this idea for a kid’s book. I want to teach kids it’s important to brush their teeth.” And you’re like, “Oh yeah, I’m sure kids are going to be really excited about that.” But when I teach writing workshops, I say, “If you write from your heart, your values are going to come out in your work without you doing anything to squeeze them in there.”

PCM: How do you maintain that childlike wonder? You said you’re a 6-year-old at heart.

Underwood: Just—I am 6. I just am. I don’t know. I think somebody once said that people who write for kids either have kids and really love kids or they are kids, and I fall into the latter category. If you ask any children’s writer, they will probably be able to say without even thinking, “Yeah, I’m 12.” My 16-year-old friends write YA. My 12-year-old friends write middle grade. And my 6-year-old friends write picture books.

PCM: What were your favorite children’s books?

Underwood:: Like many Pomona students, I’m sure, I was a pretty early reader, so I don’t really remember the picture books as much. What I remember is reading Beverly Cleary books and A Wrinkle in Time and Harriet the Spy.

I do remember my dad reading Dr. Seuss books to me. Those are great read-alouds, and I remember him reading Hop on Pop and all that. I bet if we called him up right now, he would still be able to recite the ABC book: If you said, “Painting pink pajamas. Policeman in a pail,” he would be able to finish the line. So that’s kind of a lesson in paying attention to making the adult happy enough to read the book 500 times, because you know that’s going to happen if the kid likes the book.

PCM: By virtue of being in a pandemic, what role does the outside play in this time of social distancing?

Underwood: It’s made me appreciate it so much more. When the botanical garden opened again, I wanted to go in and fall down and kiss the ground. But I do think it’s interesting that this book, Outside In, about our deep connection with nature, came out in the middle of this craziness.

I’ve always found outside to be a refuge in terms of going on walks and clearing my head and going to the park and all that. And then especially for the first few months, it became fraught because we didn’t know much about transmission. Not knowing if a jogger breathing on you would make you sick—it just added this layer of stress and anxiety onto being outside, which I’d never experienced before.

PCM: I know you don’t have an agenda per se. But one thing that came to mind when I was reading your book is the Joni Mitchell song “Big Yellow Taxi.” “They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.” How do you think this connects with environmental issues? Are you trying to communicate anything related to that in your book?

Underwood: I think if you write from your heart, your values do come out. I feel like Outside In is my environmental book. I have a book called Ogilvy. It’s about a bunny who’s wearing a garment that’s either a sweater or a dress, and the community isn’t sure which, and they’re trying to put the bunny into a box. So that’s my gender acceptance book. I just had one come out called Every Little Letter, which is about these letters and they all live surrounded by walls. So, the H is in the city of Hs, and they’re afraid of the different letters outside. There’s no metaphor there at all, obviously. The letters take down the walls at the end and they start making words and cooperating. Obviously, my values inform what I write.

PCM: Do you write every day?

Underwood: No.

PCM: I feel better as a writer.

Underwood: No. You know what? I don’t know about you, but the last several months have been so hard for every creative person that I know. I have a really strong Facebook community, and it’s very nice to be able to post, “I can’t work. I can’t even read,” and have people go, “Me neither. Me neither. Me neither.”

PCM: It happens to me that I can’t read. I haven’t read in months.

Underwood: No, no. That’s the thing. And it’s so frustrating, right? Because as soon as I heard about the shutdown, I went to the library, I checked out about 25 books. I was like, “Finally, finally, I get to read all these books.” Honestly, I think I’ve read maybe one middle-grade novel since March. I even pulled out a book that I loved when I was a kid and told myself, “Fifteen minutes. Just try to read 15 minutes a day.” And I did it for two days, and then my attention kind of fractured…

PCM: I feel really bad as a writer, but I’ve just been bingeing on Netflix.

Underwood: I think we have to, right? I tell myself—this might not be entirely true—we’re learning about story structure, right?