Coolest name for a college band: The Inland Emperors. The group formed last fall, and Wes Haas ’15 and Lee Owens-Oas ’15 came up with the moniker during their Physics with Music class. As Haas explains, they were talking about how they now live in the Inland Empire and wondering whether anyone’s ever thought whether “there’s an emperor of the place” and—voilà—the band, which includes three more Sagehens, had its name. What do they play? “Loud rock music,” says Haas. Gigs so far have mostly been on campus, but with a name like that, we’re sure their reign will someday reach all the way to Riverside.

Coolest name for a college band: The Inland Emperors. The group formed last fall, and Wes Haas ’15 and Lee Owens-Oas ’15 came up with the moniker during their Physics with Music class. As Haas explains, they were talking about how they now live in the Inland Empire and wondering whether anyone’s ever thought whether “there’s an emperor of the place” and—voilà—the band, which includes three more Sagehens, had its name. What do they play? “Loud rock music,” says Haas. Gigs so far have mostly been on campus, but with a name like that, we’re sure their reign will someday reach all the way to Riverside.

Blog Articles

Rock ‘n’ Roll Rulers

Letters to the Editor

The Great Debate

Mark Wood’s column, “When Bad Things Happen,” marks the first time I’ve been truly angered by something I read in Pomona College Magazine. While one doesn’t expect hard-hitting journalism from a publication whose main purpose is to stroke alumni and encourage donations, this was beyond the pale.

Comparing Pomona’s controversy over the firing of undocumented workers, many of whom were trying to unionize (a facet of the story Wood mysteriously omitted) to the disturbing events at Penn State, Wood waxed poetic about “when bad things happen to good institutions.” With all the subtlety of Rush Limbaugh on meth, he implied that it was somehow unfair and prejudicial not to “imagine good, caring thoughtful people agonizing over intractable problems,” suggesting that a failure to do so was the moral equivalent of blaming people with cancer or AIDS for their illness.

It’s hard to imagine a more offensive and intellectually dishonest argument. What happened at Penn State was the result of people—maybe good, maybe not so good—making truly horrible decisions, in the context of a campus culture that placed certain programs on a pedestal. It appears that seriously horrible decisions have also been made at Pomona. Whether they were in fact made by “good, caring, thoughtful people agonizing over intractable problems” remains at best a matter under dispute. In any case, good intentions are hollow without good judgment.

The decision to delay a more thorough examination of the firing controversy until the next issue was understandable, given the deadlines and lead times of a quarterly publication. To publish Woods’ apologia in the interim suggests strongly that the whitewash is well under way.

—Bruce Mirken ’78

San Francisco, Calif.

I’d like to compliment you on your article “When Bad Things Happen.” It gives proper perspective on an unfortunate situation. It reflects the thought and care I would wish of all journalists. Keep it up!—Bob Hatch ’51

Laguna Woods, Calif.

I am writing in response to President Oxtoby’s winter letter to alumni lamenting the termination of 17 college employees after the worker documentation investigation.

Few take pleasure in terminating employees. However, your sympathy may be misplaced, and your willingness to use scarce college resources to support the discharged employees seems inappropriate and misguided. While the intent of the discharged employees in working illegally may have been benign—a better life for them and their families— the results of their action were harmful:

—They broke the laws of our country by entering illegally;

—They secured employment under false pretenses and in violation of the law;

—They compromised the integrity of Pomona’s hiring practices and, thereby, stained the reputation of the College;

—They placed themselves ahead of the millions who are attempting to immigrate legally into the country;

—They deprived U.S. citizens and legal residents of employment opportunities.

Perhaps, unemployment is not an important issue for the college staff and faculty, but unemployment in California has been running over 10 percent, and at a much higher rate among African Americans. By hiring illegal immigrants,

Pomona does nothing to relieve the suffering of the unemployed. Do you not think that the College has greater obligations to our own citizens than to those who have broken our laws and violated our trust?

I strongly urge that you renounce the misguided decision to provide health insurance to the discharged employees through June 30 and, instead, use the funds for an outreach program to potential replacement employees who are citizens or legal residents, especially African Americans.

—George Zwerdling ’61

Carpinteria, Calif.

I sent this to President Oxtoby in response to his alumni/ae letter about the pain of firing undocumented college workers: Responding to the dilemma of your valued long-term employees, who happen not to be citizens, doesn’t seem so difficult an issue to me at all, if the institution has any ability to take a moral stand.

Declare Pomona College a sanctuary. Defy the damn racist law. Think of the university grounds in Mexico during 1968, declared sanctuary until the army violated it. Think of the European countries that allow non-citizens not only to reside and work, but to vote! I could go on and on and we’d inevitably end up with Jim Crow, the internment of Japanese-Americans and the anti-Jewish laws in Germany, so I won’t. Still, firing the employees without a struggle is shameful.

—John Shannon ’65

Topanga, Calif.

The Life of Liffey

Like Jake Smith ’69 (“Class Notes” Spring 2012) I was moved by the article in the Fall 2010 PCM to seek out the complete series of Jack Liffey novels by my classmate John Shannon. John and I were dorm neighbors in Walker Hall freshman year, but had little contact after that and none since graduating in 1965. Finding all of the books was made possible by Amazon’s network of sellers of used books. Some of the earlier titles are actually library discards.

I enjoyed all of the novels, some inevitably more than others, but wouldn’t hesitate to recommend the whole series, preferably read in order. The stories are well-told, the characters exceptionally well-drawn and the Los Angeles milieu fascinating. It is the latter that has drawn comparisons with Raymond Chandler, but because of the sense of history and the uncompromising social criticism I am more reminded of James Ellroy. But John’s voice is very much his own and he is driven more by indignation, where Ellroy is driven by paranoia. For a sometimes dark but always convincing vision of the hometown I left nearly 40 years ago, thank you PCM, thank you Amazon and especially thank you, John.

—Steve Sherman ’65

Munich, Germany

A Sagehen Star

I just received your spring ’12 “racing issue.” Unfortunately, it appears to be missing an alumnus story that should have been included. I’m referring to the professional track career of Will Leer ’07. Let me say up front that I’m biased. I’m the managing editor of Track & Field News, a monthly magazine that covers the elite end of Leer’s sport at the world, U.S. national and high school levels.

Will is a professional middle distance runner and aspiring Olympian, specializing in the 1500 meters, although he is now starting to explore the 5000 meters. At the ’08 Olympic Trials, he placed fourth (three make the team). At the USATF National Championships in the years since he has never placed lower than fifth. The ’09 and ’11 nationals served as trials for the World Championships, and last year Will missed a qualifying spot by 0.01 second. In 2010 at the USATF Indoor Championships, Will placed second and went on to represent the U.S. at the World Indoor Championships in Doha, Quatar.

Will spent this winter training and racing in New Zealand and Australia with training partner Nick Willis, the Beijing 1500 meters silver medalist, and other members of their training group. He spends his summers racing on the pro circuit in Europe.

Hopefully when your summer issue comes out Will Leer will be a London-bound Olympian, although this year’s 1500-meter Olympic Trials final should be as tough a nut to crack as the event has ever seen in the U.S. The story of a Sagehen competing at the highest level in his sport is compelling either way, if you ask me.

—Sieg Lindstrom ’84

San Francisco, Calif.

In Memory of David Waring

We our hoping to establish an endowed scholarship fund to memorialize our late son, David A.T. Waring ’03, who passed away at the age of 29 from the ravages of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), “an acquired neurological disease with complex global dysfunctions.” David—who played a riveting lead guitar in his college band, “Dave and the Sweatpants”—had planned to study applied mathematics and music in a graduate program before he was stricken with ME/CFS just four days after his 23rd birthday.

The scholarship would be awarded to an incoming freshman whose dream of applying science/ mathematics to an understanding of music reflects Dave’s passion. We welcome contributions from the Pomona College and the wider communities to honor our late son. Donations, which are tax-deductible, may be made to the following:

The David A. T. Waring ’03 Memorial Scholarship Fund, c/o Don Pattison, Director of Donor Relations, Pomona College, 550 North College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711.

—Alan and Pat Waring

Parents of David

Irvine, Calif.

Missing Meg Worley

During the 2011–12 academic year, Pomona College lost superstar English Professor Meg Worley to Colgate in New York. From the perspective of alumni, it happened quietly. After a protracted tenure-consideration process ended in a surprising “no,” Professor Worley decided to head east. For us English alumni, it is a sad way to say goodbye to a faculty member who provided so much stability and guidance during a period of significant changes in the English Department. From 2004 to 2011, Professor Worley saw a number of fellow English professors retire, move, or pass away (including many of the department’s institutional names: Martha Andresen, Paul Saint-Amour, David Foster Wallace, Steve Young, Rena Fraden and Cristanne Miller). During this time, her dynamic classes, patient mentoring and professionalism reinvigorated the department and it was no surprise to us when, in 2010, she won the Wig Award—the highest honor bestowed on Pomona faculty.

We would like to thank Professor Worley wholeheartedly for organizing the first senior-seminar colloquium and night readings of Beowulf; for spicing up course readings with non-traditional literary texts such as graphic novels, Arthurian myth and the Bible; for offering her grammatical expertise, without judgment, whenever the need arose; for writing countless letters of recommendation for graduate school; for always keeping her office open for impromptu visits; and for expecting a lot from students but giving back so much more. In short, she represented the best of what Pomona advertises about its instructors: individualized attention, warmth and high-level intellectualism without pretension. She was a professor who brought creativity and energy to every endeavor she undertook. As one former student wrote, “No one could mistake a Meg-graded paper as you knew any assignment would be returned, every word read, and marked with one of her colorful array of pens and extraordinarily neat handwriting.” She learned our names, kept in touch after we graduated and invited us to lunch when we returned to campus for a visit. Professor Worley was a reason to stay connected with Pomona and we are so sorry that future Sagehens will miss the opportunity to learn why.

All our best to you in New York, Meg! We should have kept you, but here’s to new beginnings:

“Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote…”

—Carlo Diy ’06

—Emily Durham ’07

—Meredith Galemore ’06

—Coty Meibeyer ’05

—Carolyn Purnell ’06

—J.B. Wogan ’06

Editor’s Note: The letter was signed by seven additional alumni.

Alumni and friends are invited to email letters to pcm@pomona.edu or to send them by mail to

Pomona College Magazine

550 North College Ave.

Claremont, CA 91711.

Letters are selected for publication based on relevance and interest to our readers and may be edited for length, style and clarity.

How to Become a Musical Mentor Multiplier

Set on enlisting Pomona student musicians to give free lessons to kids, Gabriel Friedman ’12 landed a $10,000 grant from the Donald A. Strauss Public Service Foundation to help pay for cellos, violins and other instruments. But his path to becoming a music mentor began long before that:

Set on enlisting Pomona student musicians to give free lessons to kids, Gabriel Friedman ’12 landed a $10,000 grant from the Donald A. Strauss Public Service Foundation to help pay for cellos, violins and other instruments. But his path to becoming a music mentor began long before that:

1) Get placed in a kiddie music class by your mom at age 3. Dig it. Begin piano in the second grade. Take lessons through high school.

2) Keep at the keyboard after coming to Pomona to study neuroscience. Start giving lessons after getting introduced to a mom looking for someone to teach her daughters. Around the same time, sign on as a mentor working with low-income kids for the nonprofit Uncommon Good.

3) Land a summer neuroscience fellowship in Vermont. Hear a speaker talk about the role of music training in children’s brain development. Hatch a plan to have Pomona students give music lessons to kids whose families can’t afford them.

4) Apply for a grant to buy instruments. Set off for a semester of study abroad in Europe. Get the good news about the grant in a barely-audible call over a hostel phone in Rome. Return to Pomona and start enlisting mentors.

5) See a slew of Sagehens sign up. Hold a fair for kids to check out different instruments. Watch the boys flock to the drums and electric guitars. Help the giddy kids try them out.

6) Carry on weekly lessons. Hold a big recital at the end of the year. See the young musicians perform with aplomb.

7) Hand off the program to next year’s coordinator. Prepare to apply to med school. Plan to keep at the piano.

– Mark Kendall

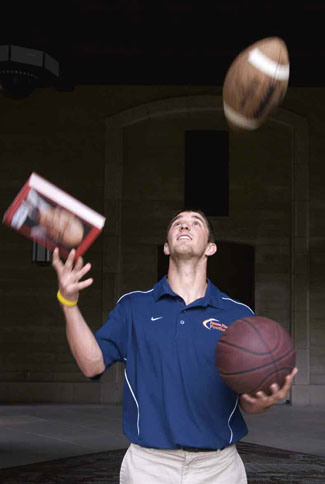

Overtime

. It wasn’t until six months after he graduated that R.J. Maki ’11 faced the most hectic day of his action packed Sagehen athletic career.

He began that fall-semester Saturday in his role as a wide receivers coach for the Pomona-Pitzer football team while the Sagehens battled Claremont-Mudd-Scripps in the season’s big rivalry game. Then, when the final horn blew around 4 p.m., he went straight to his car and drove the 60 miles across the Los Angeles Basin to play for the basketball team against Division I Pepperdine University.

Maki managed to make it to Malibu on time. His uniform didn’t.

“One of my teammates was supposed to bring my jersey for me, since I couldn’t go on the team bus,” Maki says. “Then I got to Pepperdine, and unfortunately he had forgotten it. So I had to call Jake [Caron PI ’11], and he drove it up to Malibu and finally got it to me just before halftime.” Maki ended up playing six minutes in the second half, as the Sagehens gave the Waves a run for their money before falling 59-50. “I can’t say too many people have ever had a day like that,” says Maki.

“One of my teammates was supposed to bring my jersey for me, since I couldn’t go on the team bus,” Maki says. “Then I got to Pepperdine, and unfortunately he had forgotten it. So I had to call Jake [Caron PI ’11], and he drove it up to Malibu and finally got it to me just before halftime.” Maki ended up playing six minutes in the second half, as the Sagehens gave the Waves a run for their money before falling 59-50. “I can’t say too many people have ever had a day like that,” says Maki.

Maki had graduated from Pomona in May 2011 with a degree in sociology, but there were two things that were still unfinished in Claremont: an M.B.A. from the Drucker School at Claremont Graduate University and one more season of basketball eligibility, since he missed one season due to an injury. He took a graduate assistant position with the football team, and once basketball practice started in October, his staff locker also became filled with practice gear.

The jersey run wasn’t the only time that Jake Caron has delivered something to Maki over the years. They grew up together in Claremont, attending Pomona-Pitzer games and serving as ball boys at home basketball games. The two friends left the Claremont bubble to attend Cheshire Academy in Connecticut during high school, but both returned home for college, with Caron at Pitzer and Maki at Pomona.

“When I left, it wasn’t my plan to come back necessarily,” says Maki. “But when I gained exposure to the East Coast schools … I saw how similar Pomona was. And it had the added benefit of being right in my hometown.”

The two were four-year teammates in Pomona-Pitzer football, with Caron breaking the school’s record for passing yards as a quarterback (8,408 career yards) and Maki setting the program’s receiving records (276 catches for 3,078 yards).

After coaching in the fall, Caron signed on with the Utah Blaze in arena football, while Maki multitasked in Claremont. The final basketball season turned out to be well worth it for Maki, as the Sagehens bounced back from a down year in 2010-11 and finished a close second in the SCIAC, losing the conference championship game to CMS in a nail-biter before a crowd of 2,470. That was despite having a young team that relied heavily on freshmen and sophomores.

“I wanted to do well and prove to everybody, myself included, that I could be part of a successful team,” says Maki, who played in all 26 games for his final season and scored a career-high 101 points. Freshman guard Kyle McAndrews ’15 has praise for Maki: “R.J. was able to help me, through his example and through his advice, adjust to the collegiate level.”

In helping to coach football, Maki had a chance to work with sophomore receiver Ryan Randle ’14, who made big strides as a passing target, finishing with 40 catches for 470 yards and seven touchdowns.

Maki also leaves behind his own football records that will be very difficult to beat. Though he acknowledges that he—like everyone on the football team—would have liked to have won more games during his career, it’s a sacrifice that he’s more than willing to accept for the big picture.

“There’s no way I’d trade my experience at Pomona for a few more wins,” says Maki, who has moved to San Diego to work for a private banking/wealth management firm after completing his M.B.A. a year early under a special program. “I loved my time here. The thing about Pomona is that people value athletics, but academics always comes first, and I think everyone who plays here has everything in the right perspective. No matter what happens, we’re always proud to wear the jersey and represent our school.”

Even if the jersey arrives late.

Bryan Coreas ’11: “From Those To Whom Much is Given”

Bryan Coreas ’11 has been involved with the Pomona College Academy for Youth Success (PAYS) since he was admitted to the summer program as a high school student in 2004. He worked as a student coordinator while he was attending Pomona, and this year was hired as the post-baccalaureate fellow in charge of educational outreach. When his 16-month appointment ends, he plans to attend graduate school and become a math teacher.

An Introduction

An Introduction

“I started PAYS when it was still called the Summer Scholars Enrichment Program. Back then, there wasn’t an option to live on campus during your first summer, so I commuted from La Puente. It was amazing being at Pomona and getting to meet people from other schools, learning about other students’ experiences. I knew then I had to go to college. That’s where the program had the biggest impact for me.”

Getting In

“During the school year, I would meet regularly with Laura Enriquez ’08. She was the only college advisor back then, and I remember her driving to all our houses, reminding us to keep our grades up and take our SATs. Laura, along with Wendy Chu, guided me in applying to a few colleges, including Pomona. When the acceptance letter finally came, I was at a conference for student government, so my mom called me to let me know. She was emotional about it. I was very calm: ‘All right, I got in.’ After I hung up, it sunk in, and a feeling of relief and joy set in.”

Full Circle

“I did research with Professor Roberto Garza-López and took a class from Professor Gilda Ochoa during the summer program, and both of them continued to have a big impact on me when I came to Pomona as a college student.They helped me feel I was part of a supportive community and made me think about what kind of impact I wanted to have as a teacher. One of the things I know I want to do is recreate what happened for me here—professors listening, inviting you out to grab a bite, really creating a bond with the students.”

Becoming a Teacher

“I got involved with the Draper Center during my first year. They needed Latino males to be role models for Pomona Partners’ weekly mentoring program at Fremont Academy and asked if I would help out. It was fun, and very different from what I’d been doing as a college student. It was also the first time I had hands-on experience in the classroom and it made me excited about the possibility of becoming a teacher.The next fall I started doing college advising with PAYS students and helped guide three high school students through the applications process.”

Shaping the Clay

“It’s been great to be back at the Draper Center and with PAYS. There have been so many changes in the program since I first came here, with the addition of more college advisors and community meetings in the residence halls that help students from all three classes get to know one another. As the post-bac fellow, I’m getting the chance to really dive in, to help shape the clay. After the summer, one of my projects will be working on developing a new Draper Center program for sixth- to 12th-grade students.”

“…Much is Expected”

“Pomona is a special place. It has given me a lot. Maria Tucker [director of the center] likes to say, ‘From those to whom much is given, much is expected.’ I believe in that ideology. I was given this opportunity and want to use it to the best of my ability.”

First Decade PAYS Off

When 30 high school students cross the stage in Big Bridges in July, the ceremony will not only recognize their success in completing the Pomona College Academy for Youth Success (PAYS). The event also will cap the first decade of the popular program geared toward promising teens who come from low-income families and are often the first in their families to attend college. Founded in 2003, the college access program has made it possible for participants from local high schools to attend some of the most prestigious colleges and universities in the country, including Harvard, Yale, Stanford and each of the five undergraduate Claremont Colleges. And it’s free. The high school students get room, board and classes at no charge.

Each summer, Pomona College welcomes 90 high school students to campus for the four-week academic program. The students—rising 10th-, 11th- and 12thgraders—live in one of the residence halls and attend writing seminars and math classes taught by Pomona professors. In the third year, PAYS students conduct research with professors on topics ranging from Shakespeare to robots. College students, most of them from Pomona, work as teaching and resident assistants and writing and math tutors. Each T.A. also designs and teaches an elective. “The hallmark of our program is that students start as 9th-graders and spend three consecutive summers with us,” says Maria Tucker, director of the Draper Center for Community Partnerships, which oversees PAYS. “Not many college access programs do that.”

Workshops about leadership and college admissions are offered to all students, while students about to enter their senior year meet one-on-one with members of the Pomona admissions staff to work on essays and hone their interview skills. Meals in the dining hall, pick-up Frisbee games, field trips and opportunities to participate in theatre and other extracurricular activities round out the introduction to college life. “We try to mirror the campus environment, where there are tugs on your time and you have to learn to say ‘no’ if you have work to do,” says Tucker. “We get feedback from parents, who tell us that the person they dropped off at the beginning of the summer is different from the person they picked up. They see an increased level of independence.”

The PAYS program doesn’t end after four weeks. The staff offers year-long college advising, an SAT prep program and bilingual financial aid workshops, and works with local schools to identify qualified students for the summer session. They also meet with the families of current PAYS students to talk about the steps needed to apply to college. As a result of these efforts, 100 percent of the students who graduate from PAYS go on to college, according to Tucker. In the past seven years, 24 PAYS graduates have enrolled at Pomona, the highest number of any college or university. Six of those students, who will be part of the class of ’16, will return to campus this summer for the PAYS graduation. At the end of the ceremony, they will hear their names and college destinations announced, along with those of their fellow alums. It’s an emotional moment for the students and their families, almost as much as it is for Tucker and her staff.

“You put your energy and love into it, and these kids are going to amazing colleges that many of them and their families never thought could be possible,” says Tucker. “People’s lives are forever changed.”

Sports Roundup

The difference between victory and defeat is often a slender one, but for the Sagehens of Pomona and Pitzer, the winter of 2011–12 was a time of particularly nail-biting conclusions—none more so than in women’s swimming, where Alex Lincoln ’14 pulled off not one razor-thin victory, but two in as many days.

At the SCIAC swimming and diving championship, Lincoln won what seemed to be a once-in-a-lifetime race when she captured the 200-yard freestyle by a fingertip, edging Margo Macready of Redlands by four-hundredths of a second (1:54.27 to 1:54.31). However, the following day, she pulled off another photo finish by winning the 100-yard freestyle by five-hundredths of a second (52.21 to 52.26) over Chandra Lukes of Redlands, winning her second SCIAC individual title by a combined nine-hundredths of a second.

Not to be outdone, Pomona-Pitzer’s softball team turned heads with a 10-4 record in March as it emerged as a contender for the SCIAC crown, but what was even more impressive than the record was the way the Sagehens won many of those games. Six of the 10 wins came in their final at-bat, including five walk-off wins at home and an eight-inning win at Whittier. Kathryn Rabak ’13 was responsible for two of those walk-off wins, with a three-run homer in a 7- 6 win over Staten Island, and a line-drive RBI single in a 5-4 win over Cal Lutheran.

In men’s basketball, in front of overflow crowds, inter-consortium rivals Claremont-Mudd-Scripps and Pomona-Pitzer each earned wins on the other’s home court with less than a second remaining. CMS won the first meeting at Voelkel Gymnasium with a coast-to-coast lay-up with 0.6 seconds left, moments after Jack Klukas ’15 had tied the game with a three-pointer. In the rematch at Ducey Gymnasium, CMS took a two-point lead on a three-pointer with 10 seconds to go, but Kyle McAndrews ’15 was fouled shooting a three-pointer with 0.4 seconds left and made all three pressure-packed foul shots for a 51-50 win. For the latest on Pomona-Pitzer sports, follow us on the web at www.sagehens.com.

Alumni Bulletin Board

Come Celebrate Pomona’s 125th

Pomona College’s 125th anniversary will be celebrated in 2012-13. The main event, scheduled for Founders Day, Sunday, Oct. 14, will be a grand, campus-wide, open house centered on Marston Quadrangle.

In keeping with the anniversary’s theme of community, we are reaching out not only to the immediate Pomona family—faculty, staff, trustees, students, alumni, parents—but beyond, to The Claremont Colleges, the cities of Pomona and Claremont, and particularly to school children and their families, many of whom are working with Pomona students through the Draper Center for Community Partnerships and its outreach programs.

Founders Day will offer a festive mix of events, including music and dance performances, special exhibitions, a behind-the-scenes campus tour and activities for children. We’ll also have refreshments and birthday cake for all our guests. Anniversary observances will extend throughout the year with special events and programs now in the planning stages. The virtual center of this effort will launch in the fall on the College’s web, including an innovative timeline that will both update our history and invite ongoing participation from all members of the community, thus creating a vibrant record of life at Pomona in our 125th year.

Please save Oct. 14 on your calendars now, and look for more information in coming months at www.pomona.edu/125.

Travel Study:

Sicily: Heart of the Mediterranean With History Professor Ken Wolf

May 14—26, 2013

Sicily’s position at the very heart of the Mediterranean has ensured that it would always serve as one of the world’s greatest crossroads. For centuries the island has been subject to a succession of foreign powers: Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, Tunisians, Byzantines, Normans, Aragonese and British. Join Professor Wolf and Peter Watson for this walking tour through history. Price not set at press time.

Galapagos Island Cruise With Professor of Biology and Associate Dean Jonathan Wright

August 3—12, 2013

Join Jonathan Wright on his third trip to the Galapagos Islands aboard the 48-passenger Lindblad Expeditions Islander. The animals here have no fear of humans, so you can get close to the birds, sea lions and iguanas—as well as snorkel with penguins and sea turtles. Prices start at $6,260, not including airfare. Email alumni@pomona.edu or call 909-621-8110 to request a brochure.

Beyond the Wall

1) Open the Gates … Again

By Joel Newman ’89

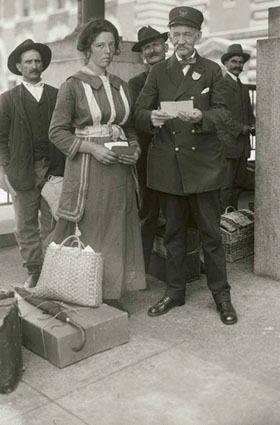

Arizona’s Joe Arpaio, the self-described “toughest sheriff in America” whose deputies have targeted undocumented immigrants, has emphasized that his parents immigrated legally to the United States from Italy in the early 1900s, according to author and journalist Jeffrey Kaye in his book Moving Millions: How Coyote Capitalism Fuels Global Migration. He differentiates his parents from 21st-century immigrants who enter “illegally.” Arpaio may not realize that if the system under which his parents came to America still existed today, most of the immigrants he targets would not be “illegal.”

Bettmann/Corbis AP Images

That more open approach served America well. In fact, we should replace our current immigration system with one similar to the old system, which generally allowed a free flow of newcomers. A 21st-century version would allow us to end today’s debate over work authorization, border enforcement, deportation and labor exploitation due to immigration status.

The immigration laws that Arpaio’s parents encountered were very different from those that exist today. Restrictions on European, Mexican, Canadian and other Western Hemisphere immigrants were few. To immigrate, they did not have to prove that they had a relative who was a U.S. citizen or legal resident, nor did they need to show that they had particular skills or prove that they were fleeing persecution. There were no annual numerical limits on immigration. Documentation was not required to work. According to Mae Ngai of Columbia University in her book Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, deportations were infrequent, and “it seemed unconscionable to expel immigrants after they had settled in the country and had begun to assimilate.”

There were provisions to exclude immigrants who arrived in the U.S. and were determined to be mentally challenged, criminals, polygamists or members of other groups, but Ngai notes that only 1 percent of the 25 million European immigrants from 1880 to World War I were excluded. This immigration system, which essentially had existed since colonial times (prior to the late 19th century, immigration had been controlled by states and colonies), ended in the 1920s with the enactment of annual numerical limits on European immigration and other immigration control features that continue to this day. This led to a dramatic reduction in European immigration levels.

A significant injustice with the older system was its ban on Chinese immigration (later to include other Asian immigrants). Notwithstanding this wrong and the concern many contemporary Americans had about the poverty, political orientation and ethnicity of many newcomers, few Americans today would claim that the much more lenient immigration system (at least toward Europeans) didn’t work. While many European immigrants suffered from horrible working conditions and nativist hostility, they were able to start new lives for themselves and their offspring. And the country immensely benefited economically and culturally. Implementing a revised version of this older system, allowing immigration from all countries and only excluding entrants for health or security reasons, would reap similar benefits today.

It’s also a matter of basic fairness. Most of today’s Americans are the beneficiaries of the relatively unfettered immigration policies for Europeans and Canadians before the 1920s. It is unjust for the majority of the public, who owe their American citizenship to the milder policies of the past, to deny today’s would-be immigrants the same opportunities. Had Arpaio’s parents faced today’s immigration laws, he likely wouldn’t be a U.S. citizen, let alone the “toughest sheriff in America.”

Joel Newman ’89 is an English as a Second Language teacher in Beaverton, Ore., working on a book advocating for open borders. He was a history major at Pomona.

2) Expand the Dream

By Will Perez ’97

Most of the efforts for immigration reform in recent years have focused on the DREAM Act, which would provide a path to legalization to approximately 800,000 young adults who meet the age, residency, college enrollment or military enlistment criteria. Many proponents of immigration reform still believe it is the most politically viable legislation. While I agree the DREAM Act is a much-needed step in the right direction—much of my academic work has focused on the issue of higher education access for undocumented immigrants—I would also make the case for a slightly wider starting point for reform, one that would improve the lives of millions of children and young adults, many of whom are already U.S. citizens.

Often forgotten in the debates about immigration reform are the 4.5 million children and adolescents who are U.S.-born citizens growing up with undocumented parents. Overall, an estimated 14.6 million people are living in some sort of mixed-status home where at least one member of the family is an undocumented immigrant. One in 10 children living in the United States is growing up in such a household. Within these mixed-status households are a range of citizenship and legal residence patterns involving siblings: some born in the U.S. with birthright citizenship, some in the process of attempting to obtain legal status and some fully undocumented.

Piotr Redlinski/Corbis / AP Images

The lack of immigration reform and absence of clear immigration policies results in negative consequences for the well-being of both U.S.-born and foreign-born youth growing up in households headed by undocumented immigrants. Children and youth in households with undocumented members live in fear of being separated from parents or other family members. More than 100,000 citizen children have experienced their parents’ deportation in the last decade. A recent survey of undocumented Latino parents found that 58 percent had a plan for the care of their children in case they were detained or deported and 40 percent had discussed that plan with their children.

Above and beyond the disadvantages faced by undocumented parents due to lower levels of education, they also are excluded from obtaining resources to help their children’s development. The threat of deportation results in lower levels of enrollment of citizen-children in programs they are eligible for, including childcare subsidies, public preschool and food stamps. It also leads to lowered interactions with public institutions such as schools. Without recourse to unions or labor law protections, these parents endure work conditions that are not only poor but chronically so. The resulting economic hardship and psychological distress bring harmful effects on children’s development. Among second-generation Latino children, those with undocumented parents fare worse on emergent reading and math skills assessments at school entry than those whose parents have legal resident status. Moreover, such disparities are evident at as early as 24 months.

Because parents’ socioeconomic status has enormous effects on children’s education, the negative influence of undocumented status may well persist into later generations. Children of undocumented immigrants have lower educational attainment compared to those whose parents are legal residents. But once undocumented immigrants find ways to legalize their status, their children’s educational levels increase substantially.

Higher education poses another set of hurdles for undocumented youth. The rare few who are able to attend college have limited access to financial support to pay for their education. Most must pay their own way, so they have to take on extra jobs and work long hours, leaving little time for studying or forcing them to take time off from school to save money. Many aim to be public servants because their lived experiences have created a desire to give back to their communities. They aspire to be doctors, lawyers and teachers, all professions for which bilingual and culturally representative candidates are greatly needed.

The DREAM Act, as proposed, would certainly benefit many undocumented young people, allowing them to attain legal status. But the undocumented status of their parents and other family members would still continue to have a negative effect on their emotional and academic well-being. Nearly 14 million individuals who live in mixed-status families would continue to suffer the devastating negative effects of undocumented status. Among them, millions of U.S.-born and foreign-born children and adolescents would still face the hardships that harm their development. Unless criteria is expanded to include all undocumented youth, their parents and the undocumented parents of U.S.-born children, the DREAM Act will fall far short of its promise to allow hardworking individuals the possibility to become fully integrated into American society so that they can fully contribute to our economic and civic vitality.

Will Perez ’97, associate professor of education at Claremont Graduate University, is author of Americans by Heart: Undocumented Latino Students and the Promise of Higher Education.

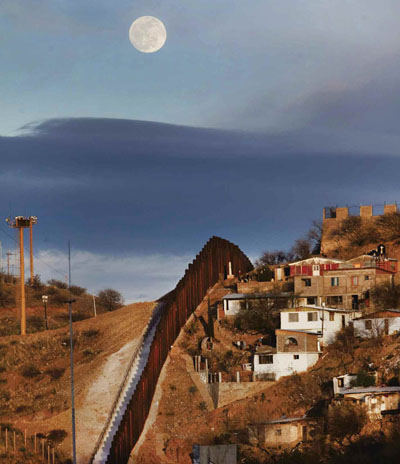

3) Secure the Border First

By Joerg Knipprath ’73

Contrary to multiculturalist and globalist dogmas fashionable among the opinion elite, Americans as a whole embrace the notion that the United States is a distinct cultural and political entity. The public understands that preserving that distinctness requires controlling immigration to promote assimilation of immigrants culturally and economically. Securing the borders becomes one means to that end, as well as being a matter of national security. It is not surprising that opinion polls show significant public support for control over illegal immigration, even for the demonized Arizona law whose supposedly controversial provision over determining some individuals’ legal residency matches long-time federal law and the laws of California and many other states.

AP Photo / Gregory Bull

As a matter of political efficacy (as well as common sense), securing the border becomes the foundational task. The principal constitutional authority lies in the federal government. Once public confidence in the government’s willingness to control the border has been restored, normalization of the status of those here for a long time or who are here illegally due to no fault of theirs would become politically more acceptable. However, the Obama administration, like its predecessors, has shown little appetite for a concerted push to control illegal migration. By default, some of the states most affected by this laxity have found it necessary to act.

They have the Constitution on their side. That compact specifically obliges the United States to protect the states against invasion. While that language preeminently applies to military invasion, it is not so limited. Incursions by pirates were a recognized threat to Americans of the late-18th century. Today’s conditions of insecurity in person and property that make the southern border area so dangerous and have taken the lives of innocent citizens are analogous to pirate depredations in earlier years. The federal government’s breach of the constitutional compact justifies the reactions of states like Arizona, from increased apprehension of illegal entrants to sending the National Guard to patrol the state’s southern border. As James Madison rightly observed in Federalist No. 41, “It is in vain tooppose constitutional barriers to the impulse of self-preservation.”

As a (legal) immigrant and son of (legal) immigrants, I very much sympathize with the desires of those who come to the United States seeking a better life. Though I was still a child then, I vividly remember the process of obtaining the right to enter and the joy that came with knowing that our family would have that opportunity. However, that experience also turns me unsympathetic to those who crash the party and make others, who obey the immigration laws, look like saps.

There is no perfect defense, and we must avoid Maginot Line thinking. But as homeowners recognize, walls, fences (both physical and virtual) and patrols can do much to advance security. Lest anyone bring up a canard about the Berlin Wall, every rational being knows the difference between a wall or fence intended to keep people in and one intended to keep interlopers out. Think Great Wall of China versus Berlin Wall; think a fence around a residence versus one around a prison. After the border has been secured, other matters can be addressed in due course.

While the current economic doldrums seem to be discouraging many illegal entrants, one hopes that economic malaise will not be the new norm. Looking to the return of more vigorous economic times, a controlled, limited guest worker program, combined with the emerging regime of employer sanctions, would help lower the incentives to enter the U.S. illegally. At the same time, the unconstitutional practice of cities designating themselves as “sanctuary cities” must be brought to an end—these cities blatantly undermine federal immigration policy.

Military service would be another way to show a civic commitment that merits a path to citizenship. Whatever the approach, there must be no cutting in line for illegal entrants over law-abiding applicants for immigration. A final step would be to end the current policy under which any child born in the U.S.—even to parents here illegally—automatically receives citizenship, opening a path for the family to stay as well. Whether this would require a constitutional amendment or might be done through a reconsideration of the current interpretation of the citizenship provision of the 14th Amendment is a complex topic going beyond the political decision to do so. As often is the case, the devil is in the details. But Americans are not eager to see a long-term subculture of metics as in ancient Athens or to embark on a “deport-’em-all” quest. Nor is there today the cultural inclination to adopt robust laws like Mexico’s regarding illegal entrants. A sustained, comprehensive and multilayered effort is needed. The support among the people is there. What is in doubt is the political will of our leaders.

Joerg Knipprath ’73 is a professor at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, where he teaches constitutional law, legal history and business law courses.

4) Avoid the Guest Worker Trap

By Conor Friedersdorf ’02

Urgent as it is to reform America’s immigration system, so that those here illegally can live better lives and newcomers can more easily become lawful residents, one sort of immigration reform is best avoided: the large-scale guest worker program. That may seem counterintuitive. During the Bush administration, the Republican Party was divided between restrictionists, who sought tougher enforcement of immigration laws; and moderates, who wanted to permit foreigners six-year stints as temporary workers before requiring that they return to their country of origin. Many liberals and libertarians decided that the latter approach improved on the status quo, even if they’d go farther given their druthers.

But the “guest worker” compromise isn’t just a means of permitting more people to improve their lives by working in America. It is the fraught codification of their status as economic inputs, as opposed to humans on their way to being civic equals. Inequality under the law is a foolish thing to create. It is contrary to America’s founding ideals. And its unintended consequences are likely to be abuse, resentment and strife, as has been the case in some European countries where guest workers were brought in to alleviate labor shortages in the years after World War II.

AP Photo/ The Charlotte Observer, Patrick Schneider

The Europeans discovered that so-called guest workers often stay. Being people, they form local attachments, marry, conceive children and accumulate stuff. In America, they’d presumably do so in neighborhoods substantially made up of other guest workers. Unable to vote, they wouldn’t get their say in how these enclaves were governed. Their legal status would be predicated upon their employment, making them more vulnerable to abuse by employers, for whom they’d be a depreciating asset with a six-year life, rather than human capital in which to invest. These inegalitarian features ought to be enough to sour liberals on the policy.

Conservatives should be wary too. For guest workers who reproduce, the result is a child who cannot be socialized by his or her noncitizen parents in civic participation. And if there is wisdom in sticking to long-held custom and tradition, it is surely worth noting that guest worker programs are a radical departure from what has been a fantastically successful model of immigration in the U.S.: When we’ve welcomed immigrants as citizens, the result has been a rapidly assimilating population that spawns generations of loyal, productive Americans.

We’ve experimented very little with guest workers. What happens if we fill low-wage jobs with temporary residents whose only loyalty to America springs from the paycheck they collect? Might it produce second class noncitizens who become understandably disaffected with a nation that never granted their equality?

Fortunately, millions of people would like to seek citizenship and become Americans. Why would we purposefully entrench a system that instead favored noncitizen guest workers, marginalizing a whole segment of the population while ensuring that, at best, they cannot become fully invested in our country’s future?

One answer is that they’d be cheaper labor than permanent residents or citizens. That’s why the business wing of the Republican Party embraced a guest worker program. For people whose intent is to increase the number of immigrants who can come here legally, the guest worker temptation should be avoided, for its short-term benefits do not justify its major cost: changing how we see immigrants from equals whose future is wrapped up with ours to temporary labor for doing jobs that are beneath us.

Conor Friedersdorf ’02 is a staff writer at The Atlantic and founding editor of The Best of Journalism.

Orozco at the Border

Crossing the border can be a cruel social leveler. For José Clemente Orozco, as for many Mexican immigrants, entering the United States proved a harsh and humiliating experience. But unlike most of his compatriots, the renowned muralist endured immigrant indignities at opposite ends of the map, on both the southern and northern edges of the U.S.

Orozco’s first and most famous frontier passage came in 1917, more than a decade before creating his heroic Prometheus at Pomona College. U.S. customs agents at Laredo, Texas, confiscated and destroyed most of the paintings he was carrying, claiming that they were somehow obscene. It was a bitter first impression of the country he had looked to for new artistic horizons. Instead, he found at first a vexing sort of censorship that would worry him for many years to come.

Orozco’s first and most famous frontier passage came in 1917, more than a decade before creating his heroic Prometheus at Pomona College. U.S. customs agents at Laredo, Texas, confiscated and destroyed most of the paintings he was carrying, claiming that they were somehow obscene. It was a bitter first impression of the country he had looked to for new artistic horizons. Instead, he found at first a vexing sort of censorship that would worry him for many years to come.

The second border incident is less notorious in art circles, though Orozco himself mentions it in his autobiography. This time, the brush with authorities didn’t involve his art. But it left a personal wound that might feel familiar to many fellow immigrants, regardless of profession, fame or social class.oro

During that same trip, Orozco made a tourist stop at Niagara Falls. At one point, he crossed into Canada to get a better view of the binational natural wonder. World War I was raging and authorities feared an assassination attempt on England’s Prince of Wales, who happened to be visiting at the same time. Adding to a climate of international tension, Orozco recalls, newspapers blared “in enormous red headlines” an account by a “yellow journalist” about Pancho Villa’s revolutionaries assaulting a train in Sonora and allegedly violating all the women on board.

“I had been there a couple of hours when a policeman detected something suspicious in my countenance and asked for my passport,” Orozco writes of his aborted Canadian sojourn. “On seeing that I was a Mexican he literally gave a jump and expelled me on the spot, himself conducting me back to the American side. ‘Mexican’ and ‘bandit’ were synonymous.”

In either incident, those border agents could not have imagined that they were deporting—or destroying the work of—an artist who was to become, in the words of Art Professor Victor Sorell, “the Michelangelo of the 20th Century.” Although somewhat overshadowed by the other two members of the esteemed troika of Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros, Orozco has gained increasing attention and respectability in the United States, especially in the past decade. He was the subject of a 2007 PBS documentary, Orozco: Man of Fire, and of a 2002 traveling exhibition, José Clemente Orozco in the United States, 1927-1934, organized by the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, site of the last of three murals the artist created during that seven-year stay in this country.

In written essays and interviews, experts paint a portrait of an artist whose life and labor were deeply and permanently influenced by his binational lifestyle. Of Mexico’s big three muralists— Los Tres Grandes—Orozco was the one who spent the most time in the United States, a total of 10 years during four separate stays—in 1917-19, 1927-34, 1940 and 1945-46. His visits coincided with the most convulsive global events of the 20th century, including both world wars. Orozco was living in New York the day the stock market crashed in 1929, becoming an artistic eyewitness who documented its aftermath in grim urban tableaus during the first years of the Great Depression. One of those paintings, 1931’s Los Muertos, depicts skyscrapers collapsing in a jagged jumble, an image that would be used 70 years later by a Mexican magazine to illustrate the tragedy of 9/11.

Seen through the prism of his immigrant experience, Orozco’s story will feel familiar even to those far from the rarefied art circles he inhabited. The Niagara Falls fiasco raises issues of xenophobia and racial profiling that still resonate to this day, almost 100 years later. Beyond that, all immigrants can relate to elements of the artist’s cross-border existence—the struggle to navigate the culture gap, to carve out a space where they’re not always welcome, to build a new life from scratch, to move forward despite crippling setbacks. In Orozco’s case, that included periods of poverty and isolation, epic failures as an artist and early public scorn for his work. Not to mention the loss of one hand in a fireworks accident as a young man, a disability that would have sidelined most aspiring muralists, since it is such a physically challenging art form.

“He certainly represents that [immigrant] spirit of gumption and upward battle,” says Laurie Coyle, who wrote, directed and produced the vivid Orozco documentary along with collaborator Rick Tejada-Flores.

The incident in Laredo came as a culture shock for Orozco. Though no records of the destroyed paintings exist, experts believe they were part of a series of watercolors called House of Tears, depicting brothel scenes. They were studies in the human psyche, not sexuality. They may have been grim and hopeless, but not titillating. “The pictures were far from immoral,” writes Orozco in his autobiography. “There was nothing shameless about them. There weren’t even any nudes.”

His reaction: Just keep moving. “At first, I was too dumbfounded to utter a word, but then when I did protest furiously, it was of no avail,” he writes, “and I sadly continued on my way to San Francisco.”

Though barely mentioned again, the border incident created a sort of philosophical angst for the artist, with long-term effects, according to Renato González Mello, professor of contemporary art at the National University of Mexico (UNAM) and the foremost expert on Orozco. The encounter represents a historic clash that flares when Latin Catholic culture meets Anglo-Saxon Protestantism, he explains. Aesthetically speaking, that clash hinges on traditional distinctions between high and low art, a dichotomy that was of particular concern to Orozco and other Mexican artists of the revolutionary era who brashly worked to breach it.

“The incident makes him see that the distinction between high and low is subject to legal definitions,” González says in a bilingual phone interview from Mexico City. “What in Mexico would be a problem of good taste or bad taste, or simply a problem of class, in the United States becomes a matter of law enforcement… This is like a completely different planet for Orozco, and he sees it as incredibly strange and irrational.”

Getting used to new rules would take time. For the two years he spent in the United States on that first visit, Orozco did not produce any art works of note. Instead, he painted movie posters and Kewpie dolls for subsistence. “I still believed that there was some law against art in the United States,” the artist is quoted saying in the documentary, “and I wasn’t taking any more chances.”

Orozco returned to Mexico in 1919, on the cusp of the country’s public mural movement. But Orozco’s first major commission in 1924 was soon plunged into chaos when angry conservative students defaced his murals at the capital’s National Preparatory School, because they considered them seditious and sacrilegious. Orozco recalls that he and Siqueiros were both “thrown out into the streets like mad dogs.”

Orozco (front row, fifth from right) with an unidentified group in Frary Hall, where he would paint his Prometheus. Photo courtesy of Honnold-Mudd Library.

The muralists managed to finish the work two years later, to great acclaim. But soon, government support for the mural movement dried up, and with it the hope for new commissions. With that discouraging backdrop, noting that “there was little to hold me in Mexico,” Orozco decided to set out once again for El Norte, arriving in New York in the winter of 1927.

“It was December and very cold,” he writes. “I knew nobody and proposed to begin all over.”

For six months, Orozco lived in virtual anonymity, until hemet American journalist Alma Reed, who was to become his agent and chief cheerleader. She had been referred to the artist by another writer, Anita Brenner, daughter of Jewish emigrants to Mexico who was familiar with his work and expressed concern for his “sad and lonely and neglected” condition. But she warned Reed that Orozco could be difficult, a man “tortured by hypersensitive nerves” who was “easily hurt.”

In her own book about Orozco, Reed recounts going to meet the artist for the first time at his basement apartment in Manhattan. Instead of a temperamental grouch, Reed found “a gentle host” with a “cordial smile” and a “vague touch of the debonair.” She was incensed by the way her fellow Americans were ignoring him, a snub she called “a breach of international courtesy.”

“Not one of our very wealthy and socially prominent art patrons or subsidized cultural institutions had made the slightest gesture of welcome to this renowned master of the long-lost technique of true fresco …,” writes Reed. Impelled by a “nebulous desire to make amends,” she vowed to “let him know that one ‘Norteamericana’ felt honored to welcome him, though somewhat belatedly, to Babylon-on-Hudson and had come to wish him all the success and happiness he so richly deserved.”

In the next few years, Reed did much to make that success happen. She would be instrumental, in fact, in helping the painter land his three mural jobs, at Pomona and Dartmouth colleges and in New York at the New School for Social Research. And she helped introduce Orozco to a diverse and stimulating set of new contacts through the Delphic Circle, an intellectual and literary salon founded by Greek poet Angelos Sikelianos around a vision of universal brotherhood. The group, which had staged the ancient Greek tragedy Prometheus Bound in Delphi the same year Orozco arrived in New York, would be extremely influential in his work.

“I think the adoration that Alma Reed demonstrated toward him, the attention he received in New York at the ashram of the Delphic Circle, that kind of deified him in the same way that Rivera had been deified,” says Sorell, university distinguished professor emeritus at Chicago State University. “His confidence must have grown exponentially.”

Orozco spent more than two years in New York before landing his first mural commission at Pomona. Meanwhile, he survived partly by catering—or caving—to the trendy demand for Mexican art that developed in the United States and Europe during the 1920s and 30s. He made paintings of what writer and curator Diane Miliotes describes as “landscapes that verge on the folkloric … with these stock images of a pueblo, or an indigenous woman and her child, and maybe a maguey plant or two.”

In an essay for the companion book to the Dartmouth exhibition, Timothy Rub notes that “Orozco developed a keen if somewhat cynical awareness of what American patrons expected of Mexican painters.” In the same book, González Mello puts it more bluntly: “The first thing Orozco does upon his arrival (in New York) is become a professional Mexican.”

Personally, the artist found the whole thing distasteful. Even in Mexico, he was harshly critical of revolutionary artists who pandered to the folkloric, glorified the indigenous or idealized the concept of nationality, or Mexicanidad, all of which had been the bread and butter of the mural movement.

In the United States, he had to deal with the market on its own terms, at least to some extent.

“He’s dealing with an audience that doesn’t know anything about Mexico, except that it’s exotic and exciting and violent,” says Miliotes, who served as in-house curator for the Hood Museum exhibition. “And there’s this wonderful vogue for it that he’s trying to take advantage of, but it forces him to try to navigate that craze without feeling that he’s totally selling himself out.”

Those concerns would soon fade. In 1930, Orozco put himself firmly on the map as a world-class artist with his own daring identity when he painted Prometheus, the first fresco by a Mexican artist in the United States. The commission for the space above the fireplace in Frary Hall was pushed along by Catalan art historian José Pijoán, who was then teaching at Pomona.

At first, he considered calling on Orozco’s rival, Diego Rivera. But it was Pijoán’s colleague, artist Jorge Juan Crespo de la Serna, who steered the project to Orozco. Crespo de la Serna, then teaching at Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, was a friend of Orozco and would become his assistant on Prometheus. “… The beauty of it is that a few kids and a few penniless professors had the faith and the courage to institute the proceedings and went ahead without committees, boards, or rubber stamps,” Pijoan wrote in the Los Angeles Times shortly after the work was completed.

The landmark work would become “the first major modern fresco in this country and thus epochal in the history of the medium,” according to the late art historian David W. Scott, former chair of the Art Department at Scripps College.

Yet, as bold as the fresco was, Orozco at first avoided painting a penis on Prometheus, the heroic nude that towers over diners at Frary. While more lofty artistic considerations about classic representations of the male physique may also have been at play, the artist was certainly well aware of his local critics and the risk of offending puritanical community standards. “Absolutely, I think he was hesitant (to add the penis) because there was disapproval that he was painting a very large naked male figure on the wall,” says Coyle, the documentarian. “He was reading the press and some of these critical articles were actually appearing while he was working on the mural.”

Yet, as bold as the fresco was, Orozco at first avoided painting a penis on Prometheus, the heroic nude that towers over diners at Frary. While more lofty artistic considerations about classic representations of the male physique may also have been at play, the artist was certainly well aware of his local critics and the risk of offending puritanical community standards. “Absolutely, I think he was hesitant (to add the penis) because there was disapproval that he was painting a very large naked male figure on the wall,” says Coyle, the documentarian. “He was reading the press and some of these critical articles were actually appearing while he was working on the mural.”

Orozco didn’t have to check the newspapers to find condemnation. He embarked on the project, he writes, “to the disgust of the trustees who would grumble as they made their way through the refectory and eye the scaffoldings askance, disposed to fall upon me at the first mis-step.”

A penis was appended later to the fresco when Orozco returned for a visit months later, but it didn’t adhere properly because the wall had dried. Since then, of course, the missing member has been the subject of student jokes and pranks. The genital shortcomings didn’t deter artist Jackson Pollock, an Orozco admirer, from famously declaring Prometheus “the greatest painting in North America.”

Despite the controversy, the Pomona campus community, especially faculty and students, defended the artist’s right to express himself. The following year, in the face of yet another public outcry, administrators of the New School defended his depiction of Lenin and Stalin in his series of five frescoes with sociopolitical themes. The support in both cases must have been reassuring since he had seen how vicious public censorship could be, on both sides of the border. Later, the Dartmouth community also would stand up for his artistic freedom at a time when murals by Rivera in New York and Siqueiros in Los Angeles were being whitewashed or destroyed for political reasons.

Orozco returned to Mexico in triumph in 1934 and proceeded to create astonishing works of art that mark the pinnacle of his career. He completed his masterwork at Guadalajara’s Hospicio Cabañas, crowned by the soaring image of The Man of Fire in the cupola of the colonial structure, dubbed the Sistine Chapel of the Americas. In 1940, hailed as a celebrity, he returned to New York and created the anti-war mural, Dive Bomber and Tank, commissioned by the Museum of Modern Art. Orozco wrote his final chapter in the United States in 1945-46, near the end of his life. This time, the trip was primarily personal. He came to this country for the last time out of love. And he left with a broken heart.

Earlier, the aging artist had fallen head over heels for the young and beautiful lead dancer for the Mexico City Ballet, Gloria Campobello. But when his mistress gave him an ultimatum and his wife Margarita refused to give him a divorce, the stage was set for a midlife crisis that ripped open the man’s hermetic heart.

Orozco left his family and moved to New York to be with Campobello. But she soon abandoned him and returned to Mexico, ignoring his pathetic, pining letters. The artist found himself alone in Manhattan once again, just as he had started. Now all he wanted was to go back home and he begged his wife to take him back: “I know that I have behaved very badly with you and I have paid dearly with my remorse,” he wrote. “I don’t want to live here anymore. I don’t want any of it. Or even to see it again. My only thought is to return to you if you will take me back.”

And she did. He returned to Mexico City, with only three more years to live. His final works evinced a premonition of death. When it finally came, on Sept. 7, 1949, it caught him in the midst of a new project, painting a public housing mural.

Orozco had come to this country as an unknown, and left as an artist of global stature. Far from leveling him, immigration had vaulted him to new heights.

“I really think his experience in the United States inspired him to speak to people across borders,” says Coyle, the documentary filmmaker. “He did not want to be seen as a national artist or a Mexican artist. He really kind of chafed at those boundaries and divisions that people used to define themselves and what they were doing.”

To Shine in the West

On a summer day in 1922, as the strains of opera music and applause from the commencement audience faded away, President James Blaisdell presented a doctor of laws to Fong Foo Sec, the College’s first Chinese immigrant student. It was only the third LL.D awarded since the College’s founding 35 years earlier, and the story of a peasant laborer turned goodwill ambassador receiving an honorary degree attracted coverage from as far afield as the New York Times.

Fong had become the chief English editor of the Commercial Press, China’s first modern publisher. At Commencement, he was praised as an “heir by birth to the wisdom of an ancient and wonderful people; scholar as well of Western learning; holding all these combined riches in the services of a great heart; internationalist, educator, modest Christian gentleman.”

Fong had become the chief English editor of the Commercial Press, China’s first modern publisher. At Commencement, he was praised as an “heir by birth to the wisdom of an ancient and wonderful people; scholar as well of Western learning; holding all these combined riches in the services of a great heart; internationalist, educator, modest Christian gentleman.”

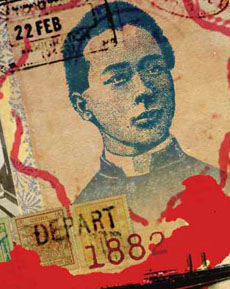

The pomp could not have been more different than Fong’s arrival four decades earlier, when his improbable journey to Pomona began under the cover of twilight. After his steamship docked in San Francisco in 1882, the scrawny 13-year-old boy hid in a baggage cart, while his fellow passengers banded together to fend off attackers along the waterfront, in case the immigrants were discovered before reaching the sanctuary of Chinatown.

“I was received with bricks and kicks,” Fong said, describing his reception in a magazine interview and in his memoirs decades later. “Some rude Americans, seeing Chinese laborers flock in and finding no way to stop them, threw street litter at us to vent their fury.”

Fong’s immigrant tale is both emblematic and exceptional: emblematic in the peasant roots, the struggles and dream of prosperity he shared with Chinese laborers of that era. Exceptional in the fact that Fong, though he came as a laborer, was able to get a college education in the U.S. and seize the opportunities it brought. He arrived at a time when formal immigration restrictions were scant, but also to a land gripped by anti-Chinese hysteria, just before a new law that, in the words of historian Erika Lee, “forever changed America’s relationship to immigration.”

IF FONG, IN HIS TINY VILLAGE in Guangdong province in southern China, had heard of such threats against his countrymen, he remained undeterred in his quest to go to Gold Mountain, a name California had picked up during the Gold Rush era. Fong’s childhood nicknames, Kuang Yaoxi, “to shine in the West” and Kuang Jingxi “to respect the West” are revealing. “He was expected, or perhaps destined, to become associated with the Western world and Western culture,” says Leung Yuen Sang, chairman of the History Department at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who has conducted research on Fong.

Born in 1869, Fong tended his family’s water buffalo and planted rice, taro and sweet potatoes, but did not begin school until he was 8. Often hungry, he went barefoot and wore patched clothes, reserving his shoes for festival days, Fong wrote in his memoirs. But his father saw a way out for Fong. From the start of the 19th century, his clansmen, driven by bandits, floods, war and rebellion, went abroad to seek their fortunes. After seeing villagers travel to America and return with “their pockets full,” his father asked Fong if he’d like to go too.

To pay for his ticket, the family borrowed money from relatives and friends, a common practice for would-be travelers. In January 1882, accompanied by his neighbor, Fong left for Hong Kong where he stayed before sailing for San Francisco on the S.S. China. In the crowded hold, amid stormy weather and high waves, he learned his first words of English and picked up advice. Fong’s steamship was one of scores jammed with thousands of his compatriots who began rushing over while the U.S. Congress debated a moratorium on most immigration from China.

According to his memoirs, Fong arrived sometime after the passage, on May 6, 1882, of what became known as the Exclusion Act, but before it took effect 90 days later. The San Francisco Chronicle published the arrivals and passenger load of steamships from the Orient, noting in March of that year, “It is a matter of some interest to know just how many Chinese are likely to be pressed upon our shores.”

The Chronicle also wrote of crowded, unclean conditions aboard steamers, which were anchored on quarantine grounds and fumigated to prevent the spread of smallpox. In headline after headline, the newspaper created the sense of a city besieged: “More Chinese: Another Thousand Arrive in This Port,” “And Still They Come … Two Thousand Others on the Way,” “Another Chinese Cargo: Eighty Thousand Heathen Awaiting Shipment to This City.”

ANTI-CHINESE SENTIMENT had been building for decades on the West Coast. During economic downturns, the immigrants, with their cheap labor, became scapegoats. Mob violence flared against them, and in San Francisco, in 1877, thousands of rioters attacked Chinese laundries and the wharves of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, the chief transpacific carriers of the laborers.

California had already passed its own anti-Chinese measures, and after years of pressure, particularly from the West Coast, Congress took unprecedented federal action in the form of 1882’s Exclusion Act. The 10-year ban on Chinese laborers would be the first federal moratorium barring immigration based upon race and class. Only merchants, teachers, students and their servants would be permitted to enter thereafter.

At first, confusion reigned. When the Exclusion Act took effect, a Chronicle headline proclaimed that the arrival of the “last cargo” of Chinese in San Francisco was “A Scene that Will Become Historical.” Still, the Chinese continued arriving as enforcement in the beginning remained haphazard. The act represented the U.S. government’s first attempts to process immigrants, and officials at the ports weren’t sure how to handle Chinese laborers under the new regulations, says Erika Lee, director of the Asian American Studies Program at the University of Minnesota. But in time the law succeeded in reducing Chinese immigration, which plummeted from 39,579 in 1882 to only 10 people, five years later. The Chinese population in the West shrank, as immigrants moved east to work and open small businesses. In the months and years to come, restrictions would tighten, with Chinese required to carry certificates of registration verifying legal entry. Later on, the right to re-enter the U.S. would be rescinded, and the act would be renewed.

“Beginning in 1882, the United States stopped being a nation of immigrants that welcomed foreigners without restrictions,” Lee argues in her book, At America’s Gates. “For the first time in its history, the United States began to exert federal control over immigrants at its gates and within its borders, thereby setting standards, by race, class, and gender for who was to be welcomed into this country.”

AFTER ARRIVING IN SAN FRANCISCO, Fong was forced to hide in a basement his first few days in Chinatown, a neighborhood of narrow alleys and cramped tenements, but also of temples and gaily-painted balconies. Laws targeting Chinese—their tight living quarters and their use of poles to carry loads on sidewalks— reflected the simmering resentment. “The city authorities, because they had not been able to prevent their coming, tried to make it difficult for [the Chinese] to settle down here,” Fong wrote.

Like many immigrants, Fong turned to kinsmen for help. He left for Sacramento to live with an uncle, a vegetable dealer, who found him a job as a cook to a wealthy family. He earned $1 a week, along with the occasional gift of a dime, which he treasured “as gold.” He—like many Chinese immigrants—sent money back to cover the debt incurred to cover his passage to America and pay for family expenses.

Like many immigrants, Fong turned to kinsmen for help. He left for Sacramento to live with an uncle, a vegetable dealer, who found him a job as a cook to a wealthy family. He earned $1 a week, along with the occasional gift of a dime, which he treasured “as gold.” He—like many Chinese immigrants—sent money back to cover the debt incurred to cover his passage to America and pay for family expenses.

At his uncle’s urging, Fong studied English at a night school set up by the Congregational Church in Sacramento’s Chinatown, but he started gambling and stopped going to class. Scolded by his uncle, he returned to school and a new teacher, Rev. Chin Toy, became his mentor.

Fong found himself debating whether to convert to Christianity. Among his parents, relatives, and friends, not a single one was Christian, and he hesitated giving up the idols his ancestors had worshipped for generations. “If Christianity turns out to be unreliable, I will lose heavily,” he wrote in his memoirs.

After a fire gutted the heart of Sacramento’s Chinatown and destroyed his few possessions, Fong had to move into a dark basement room, thick with his uncle’s opium smoke. Fong then asked if he could stay in the mission church, and Rev. Chin consented to the unprecedented request. From age 15 to 17, Fong lived in the mission, where he learned Chinese, the Bible, English, elementary science, and read books such as Pilgrim’s Progress and Travels in Africa. Six months later, he was baptized, but it took the Salvation Army to stoke his religious passion.

Drawn by the sound of the bugle one night, coming home from his cook’s job, Fong watched the preachers in the street, fervent despite a jeering crowd. Their zeal led him to question his faith and whether his sins had been forgiven. Struck by a vision of Christ’s breast streaming with blood, he knelt during a church service and repented.

His conversion was unusual—missionaries in those days did not make deep inroads among Chinese immigrants, who “did not seem to see the efficacy of a god who sacrificed his son on a cross,” says Madeline Hsu, director of the Center for Asian American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. “Until there was a better sense of community and utility in attending church, missionaries seemed largely ineffectual.”

The Salvation Army, unable to proselytize among the Chinese until Fong joined up, sent him to their San Francisco headquarters in 1889 for six months of training. As a preacher, Fong became the object of “laughter, bullying, and insults. As a Chinese, I suffered more than any Westerner,” he wrote. Still, for more than a year, Fong evangelized in California, Oregon and Washington.

One night, a brawny man in the street started beating Fong, who could not defend himself, and the teenager escaped after a woman intervened. Another time, while Fong passed a football field, boys swarmed around him, spitting and assaulting him until he found refuge in a nearby house.