1) Open the Gates … Again

By Joel Newman ’89

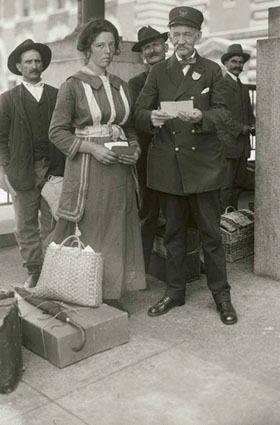

Arizona’s Joe Arpaio, the self-described “toughest sheriff in America” whose deputies have targeted undocumented immigrants, has emphasized that his parents immigrated legally to the United States from Italy in the early 1900s, according to author and journalist Jeffrey Kaye in his book Moving Millions: How Coyote Capitalism Fuels Global Migration. He differentiates his parents from 21st-century immigrants who enter “illegally.” Arpaio may not realize that if the system under which his parents came to America still existed today, most of the immigrants he targets would not be “illegal.”

Bettmann/Corbis AP Images

That more open approach served America well. In fact, we should replace our current immigration system with one similar to the old system, which generally allowed a free flow of newcomers. A 21st-century version would allow us to end today’s debate over work authorization, border enforcement, deportation and labor exploitation due to immigration status.

The immigration laws that Arpaio’s parents encountered were very different from those that exist today. Restrictions on European, Mexican, Canadian and other Western Hemisphere immigrants were few. To immigrate, they did not have to prove that they had a relative who was a U.S. citizen or legal resident, nor did they need to show that they had particular skills or prove that they were fleeing persecution. There were no annual numerical limits on immigration. Documentation was not required to work. According to Mae Ngai of Columbia University in her book Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America, deportations were infrequent, and “it seemed unconscionable to expel immigrants after they had settled in the country and had begun to assimilate.”

There were provisions to exclude immigrants who arrived in the U.S. and were determined to be mentally challenged, criminals, polygamists or members of other groups, but Ngai notes that only 1 percent of the 25 million European immigrants from 1880 to World War I were excluded. This immigration system, which essentially had existed since colonial times (prior to the late 19th century, immigration had been controlled by states and colonies), ended in the 1920s with the enactment of annual numerical limits on European immigration and other immigration control features that continue to this day. This led to a dramatic reduction in European immigration levels.

A significant injustice with the older system was its ban on Chinese immigration (later to include other Asian immigrants). Notwithstanding this wrong and the concern many contemporary Americans had about the poverty, political orientation and ethnicity of many newcomers, few Americans today would claim that the much more lenient immigration system (at least toward Europeans) didn’t work. While many European immigrants suffered from horrible working conditions and nativist hostility, they were able to start new lives for themselves and their offspring. And the country immensely benefited economically and culturally. Implementing a revised version of this older system, allowing immigration from all countries and only excluding entrants for health or security reasons, would reap similar benefits today.

It’s also a matter of basic fairness. Most of today’s Americans are the beneficiaries of the relatively unfettered immigration policies for Europeans and Canadians before the 1920s. It is unjust for the majority of the public, who owe their American citizenship to the milder policies of the past, to deny today’s would-be immigrants the same opportunities. Had Arpaio’s parents faced today’s immigration laws, he likely wouldn’t be a U.S. citizen, let alone the “toughest sheriff in America.”

Joel Newman ’89 is an English as a Second Language teacher in Beaverton, Ore., working on a book advocating for open borders. He was a history major at Pomona.

2) Expand the Dream

By Will Perez ’97

Most of the efforts for immigration reform in recent years have focused on the DREAM Act, which would provide a path to legalization to approximately 800,000 young adults who meet the age, residency, college enrollment or military enlistment criteria. Many proponents of immigration reform still believe it is the most politically viable legislation. While I agree the DREAM Act is a much-needed step in the right direction—much of my academic work has focused on the issue of higher education access for undocumented immigrants—I would also make the case for a slightly wider starting point for reform, one that would improve the lives of millions of children and young adults, many of whom are already U.S. citizens.

Often forgotten in the debates about immigration reform are the 4.5 million children and adolescents who are U.S.-born citizens growing up with undocumented parents. Overall, an estimated 14.6 million people are living in some sort of mixed-status home where at least one member of the family is an undocumented immigrant. One in 10 children living in the United States is growing up in such a household. Within these mixed-status households are a range of citizenship and legal residence patterns involving siblings: some born in the U.S. with birthright citizenship, some in the process of attempting to obtain legal status and some fully undocumented.

Piotr Redlinski/Corbis / AP Images

The lack of immigration reform and absence of clear immigration policies results in negative consequences for the well-being of both U.S.-born and foreign-born youth growing up in households headed by undocumented immigrants. Children and youth in households with undocumented members live in fear of being separated from parents or other family members. More than 100,000 citizen children have experienced their parents’ deportation in the last decade. A recent survey of undocumented Latino parents found that 58 percent had a plan for the care of their children in case they were detained or deported and 40 percent had discussed that plan with their children.

Above and beyond the disadvantages faced by undocumented parents due to lower levels of education, they also are excluded from obtaining resources to help their children’s development. The threat of deportation results in lower levels of enrollment of citizen-children in programs they are eligible for, including childcare subsidies, public preschool and food stamps. It also leads to lowered interactions with public institutions such as schools. Without recourse to unions or labor law protections, these parents endure work conditions that are not only poor but chronically so. The resulting economic hardship and psychological distress bring harmful effects on children’s development. Among second-generation Latino children, those with undocumented parents fare worse on emergent reading and math skills assessments at school entry than those whose parents have legal resident status. Moreover, such disparities are evident at as early as 24 months.

Because parents’ socioeconomic status has enormous effects on children’s education, the negative influence of undocumented status may well persist into later generations. Children of undocumented immigrants have lower educational attainment compared to those whose parents are legal residents. But once undocumented immigrants find ways to legalize their status, their children’s educational levels increase substantially.

Higher education poses another set of hurdles for undocumented youth. The rare few who are able to attend college have limited access to financial support to pay for their education. Most must pay their own way, so they have to take on extra jobs and work long hours, leaving little time for studying or forcing them to take time off from school to save money. Many aim to be public servants because their lived experiences have created a desire to give back to their communities. They aspire to be doctors, lawyers and teachers, all professions for which bilingual and culturally representative candidates are greatly needed.

The DREAM Act, as proposed, would certainly benefit many undocumented young people, allowing them to attain legal status. But the undocumented status of their parents and other family members would still continue to have a negative effect on their emotional and academic well-being. Nearly 14 million individuals who live in mixed-status families would continue to suffer the devastating negative effects of undocumented status. Among them, millions of U.S.-born and foreign-born children and adolescents would still face the hardships that harm their development. Unless criteria is expanded to include all undocumented youth, their parents and the undocumented parents of U.S.-born children, the DREAM Act will fall far short of its promise to allow hardworking individuals the possibility to become fully integrated into American society so that they can fully contribute to our economic and civic vitality.

Will Perez ’97, associate professor of education at Claremont Graduate University, is author of Americans by Heart: Undocumented Latino Students and the Promise of Higher Education.

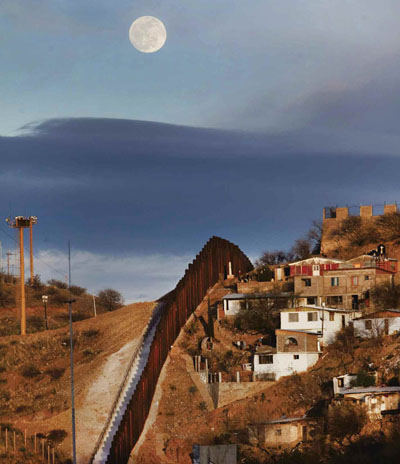

3) Secure the Border First

By Joerg Knipprath ’73

Contrary to multiculturalist and globalist dogmas fashionable among the opinion elite, Americans as a whole embrace the notion that the United States is a distinct cultural and political entity. The public understands that preserving that distinctness requires controlling immigration to promote assimilation of immigrants culturally and economically. Securing the borders becomes one means to that end, as well as being a matter of national security. It is not surprising that opinion polls show significant public support for control over illegal immigration, even for the demonized Arizona law whose supposedly controversial provision over determining some individuals’ legal residency matches long-time federal law and the laws of California and many other states.

AP Photo / Gregory Bull

As a matter of political efficacy (as well as common sense), securing the border becomes the foundational task. The principal constitutional authority lies in the federal government. Once public confidence in the government’s willingness to control the border has been restored, normalization of the status of those here for a long time or who are here illegally due to no fault of theirs would become politically more acceptable. However, the Obama administration, like its predecessors, has shown little appetite for a concerted push to control illegal migration. By default, some of the states most affected by this laxity have found it necessary to act.

They have the Constitution on their side. That compact specifically obliges the United States to protect the states against invasion. While that language preeminently applies to military invasion, it is not so limited. Incursions by pirates were a recognized threat to Americans of the late-18th century. Today’s conditions of insecurity in person and property that make the southern border area so dangerous and have taken the lives of innocent citizens are analogous to pirate depredations in earlier years. The federal government’s breach of the constitutional compact justifies the reactions of states like Arizona, from increased apprehension of illegal entrants to sending the National Guard to patrol the state’s southern border. As James Madison rightly observed in Federalist No. 41, “It is in vain tooppose constitutional barriers to the impulse of self-preservation.”

As a (legal) immigrant and son of (legal) immigrants, I very much sympathize with the desires of those who come to the United States seeking a better life. Though I was still a child then, I vividly remember the process of obtaining the right to enter and the joy that came with knowing that our family would have that opportunity. However, that experience also turns me unsympathetic to those who crash the party and make others, who obey the immigration laws, look like saps.

There is no perfect defense, and we must avoid Maginot Line thinking. But as homeowners recognize, walls, fences (both physical and virtual) and patrols can do much to advance security. Lest anyone bring up a canard about the Berlin Wall, every rational being knows the difference between a wall or fence intended to keep people in and one intended to keep interlopers out. Think Great Wall of China versus Berlin Wall; think a fence around a residence versus one around a prison. After the border has been secured, other matters can be addressed in due course.

While the current economic doldrums seem to be discouraging many illegal entrants, one hopes that economic malaise will not be the new norm. Looking to the return of more vigorous economic times, a controlled, limited guest worker program, combined with the emerging regime of employer sanctions, would help lower the incentives to enter the U.S. illegally. At the same time, the unconstitutional practice of cities designating themselves as “sanctuary cities” must be brought to an end—these cities blatantly undermine federal immigration policy.

Military service would be another way to show a civic commitment that merits a path to citizenship. Whatever the approach, there must be no cutting in line for illegal entrants over law-abiding applicants for immigration. A final step would be to end the current policy under which any child born in the U.S.—even to parents here illegally—automatically receives citizenship, opening a path for the family to stay as well. Whether this would require a constitutional amendment or might be done through a reconsideration of the current interpretation of the citizenship provision of the 14th Amendment is a complex topic going beyond the political decision to do so. As often is the case, the devil is in the details. But Americans are not eager to see a long-term subculture of metics as in ancient Athens or to embark on a “deport-’em-all” quest. Nor is there today the cultural inclination to adopt robust laws like Mexico’s regarding illegal entrants. A sustained, comprehensive and multilayered effort is needed. The support among the people is there. What is in doubt is the political will of our leaders.

Joerg Knipprath ’73 is a professor at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles, where he teaches constitutional law, legal history and business law courses.

4) Avoid the Guest Worker Trap

By Conor Friedersdorf ’02

Urgent as it is to reform America’s immigration system, so that those here illegally can live better lives and newcomers can more easily become lawful residents, one sort of immigration reform is best avoided: the large-scale guest worker program. That may seem counterintuitive. During the Bush administration, the Republican Party was divided between restrictionists, who sought tougher enforcement of immigration laws; and moderates, who wanted to permit foreigners six-year stints as temporary workers before requiring that they return to their country of origin. Many liberals and libertarians decided that the latter approach improved on the status quo, even if they’d go farther given their druthers.

But the “guest worker” compromise isn’t just a means of permitting more people to improve their lives by working in America. It is the fraught codification of their status as economic inputs, as opposed to humans on their way to being civic equals. Inequality under the law is a foolish thing to create. It is contrary to America’s founding ideals. And its unintended consequences are likely to be abuse, resentment and strife, as has been the case in some European countries where guest workers were brought in to alleviate labor shortages in the years after World War II.

AP Photo/ The Charlotte Observer, Patrick Schneider

The Europeans discovered that so-called guest workers often stay. Being people, they form local attachments, marry, conceive children and accumulate stuff. In America, they’d presumably do so in neighborhoods substantially made up of other guest workers. Unable to vote, they wouldn’t get their say in how these enclaves were governed. Their legal status would be predicated upon their employment, making them more vulnerable to abuse by employers, for whom they’d be a depreciating asset with a six-year life, rather than human capital in which to invest. These inegalitarian features ought to be enough to sour liberals on the policy.

Conservatives should be wary too. For guest workers who reproduce, the result is a child who cannot be socialized by his or her noncitizen parents in civic participation. And if there is wisdom in sticking to long-held custom and tradition, it is surely worth noting that guest worker programs are a radical departure from what has been a fantastically successful model of immigration in the U.S.: When we’ve welcomed immigrants as citizens, the result has been a rapidly assimilating population that spawns generations of loyal, productive Americans.

We’ve experimented very little with guest workers. What happens if we fill low-wage jobs with temporary residents whose only loyalty to America springs from the paycheck they collect? Might it produce second class noncitizens who become understandably disaffected with a nation that never granted their equality?

Fortunately, millions of people would like to seek citizenship and become Americans. Why would we purposefully entrench a system that instead favored noncitizen guest workers, marginalizing a whole segment of the population while ensuring that, at best, they cannot become fully invested in our country’s future?

One answer is that they’d be cheaper labor than permanent residents or citizens. That’s why the business wing of the Republican Party embraced a guest worker program. For people whose intent is to increase the number of immigrants who can come here legally, the guest worker temptation should be avoided, for its short-term benefits do not justify its major cost: changing how we see immigrants from equals whose future is wrapped up with ours to temporary labor for doing jobs that are beneath us.

Conor Friedersdorf ’02 is a staff writer at The Atlantic and founding editor of The Best of Journalism.