A FAMILIAR CLICHÉ for highly successful athletes is that they may need bigger mantelpieces to hold their many trophies. Vicky Gyorffy ’15 may need an extra fireplace.

As a member of the women’s swimming and diving and women’s waterpolo teams, Gyorffy was a part of nine SCIAC Championships. Her 800-yard freestyle relay team took first at the SCIAC Championships three years in a row. As an individual, she swept the 100- and 200-yard freestyle events in her senior year. Meanwhile, her women’s water polo team won at least a share of the SCIAC title in all four of her seasons.

And that’s not all. Gyorffy also advanced to the NCAA Division III Women’s Swimming and Diving Championships in 2014 and 2015, earning honorable-mention All-America honors, and she was an honorable mention All-America selection in water polo, while helping the Sagehens to the NCAA Championships in 2012 and 2013.

It is easy to see how Gyorffy got hooked on water sports. Her older sisters were swimmers and water polo players in high school, with Janelle graduating from Pomona in 2009 after playing both sports and Rachele graduating from Princeton in 2013 after focusing solely on water polo. Both competed in the NCAA Women’s Water Polo Championships in 2012 and 2013.

With a strong background in aquatic sports, and from a high-achieving family academically, Gyorffy had a lot of options, but ended up following in Janelle’s footsteps at Pomona, although sports wasn’t a major part of her decision.

“I wasn’t even sure I wanted to compete in sports in college, which is sort of ironic since I ended up competing in two of them,” she says. “I was just looking for a small school that was great academically, and I didn’t want to be too close to home. I think Janelle probably convinced me that the 5C environment was unique and that choosing Division III sports was a nice way to go. It’s really competitive, but not the super-intense environment than larger schools can be.”

In addition to all the athletic championships, Gyorffy has prospered academically, graduating in May as an economics major with a computer science minor. In 2014, she had a unique chance for a summer internship at Twitter headquarters working with the Girls Who Code immersion program, a six-week course in which she taught computer programming to high school girls.

“The Girls Who Code internship came about through the [Career Development Office’s] Claremont Connect program,” says Gyorffy. “Pomona was amazing, the way they helped fund that internship and make it a reality. The internship only offered a small stipend and the Bay Area is expensive, so I don’t think I could have done it without Pomona’s assistance.”

Gyorffy will start a full-time job next year as a tech consultant with a software company, which will allow her to apply both her economics degree and her passion for technology. “The job is sort of a hybrid between the business side and the software side. You need a tech background, but you can act as sort of a bridge between the software developers and the clients.”

Some people find balancing one sport and academics to be difficult. Gyorffy competed in two sports, which overlapped in the spring, and still achieved great things in the classroom. But she insists it wasn’t as challenging as it seems.

“Balancing academics and athletics wasn’t too difficult,” she says. “I like being busy and doing different things, and the coaches are great here at allowing you to focus on your academics first. What was difficult was balancing the overlap between swimming and water polo, especially the last couple of years. Going to nationals in swimming extended the winter a little more.”

The time spent swimming paid dividends her senior year with her 100-200 sweep at the SCIAC Championships. “I think this year I just wanted to get on the podium really badly, since it was my last chance, and I ended up winning. I think winning the 200 may have been my favorite moment of my athletics career, since I wasn’t expecting it.”

She won the 200 by just four-hundredths of a second, as she finished in 1:53.77, almost a second and a half ahead of her finals time from a year before. The next day, she added a more comfortable win (by 2/3 of a second) in the 100 with a time of 52.67, a full second faster than a year prior.

Gyorffy had a storybook ending to her swimming season, but she ended her water polo career with the opposite feeling. After winning the SCIAC title outright their first three seasons, she and her six classmates all had visions of making it four in a row and returning to the NCAA Championships. But after going undefeated in the SCIAC during the regular season, they were upset in the finals of the SCIAC Tournament by Whittier 7–6. The two teams were officially co-champions, but the loss brought Pomona-Pitzer’s season to a premature end.

“Of course, we were all disappointed, but we are not going to think of one game when we look back,” she says. “It’s going to be all about the journey of the whole four years. Maybe it wasn’t the storybook ending we had hoped for, but we’ve been on the other side of those close games many times, so maybe it was only fair that it came back around.

“For me personally,” she says, “I think losing one maybe makes me appreciate the three we did win even more now. It’s hard to win a championship, and a lot of athletes give it their all and never get the chance to experience it.”

Much less nine times.

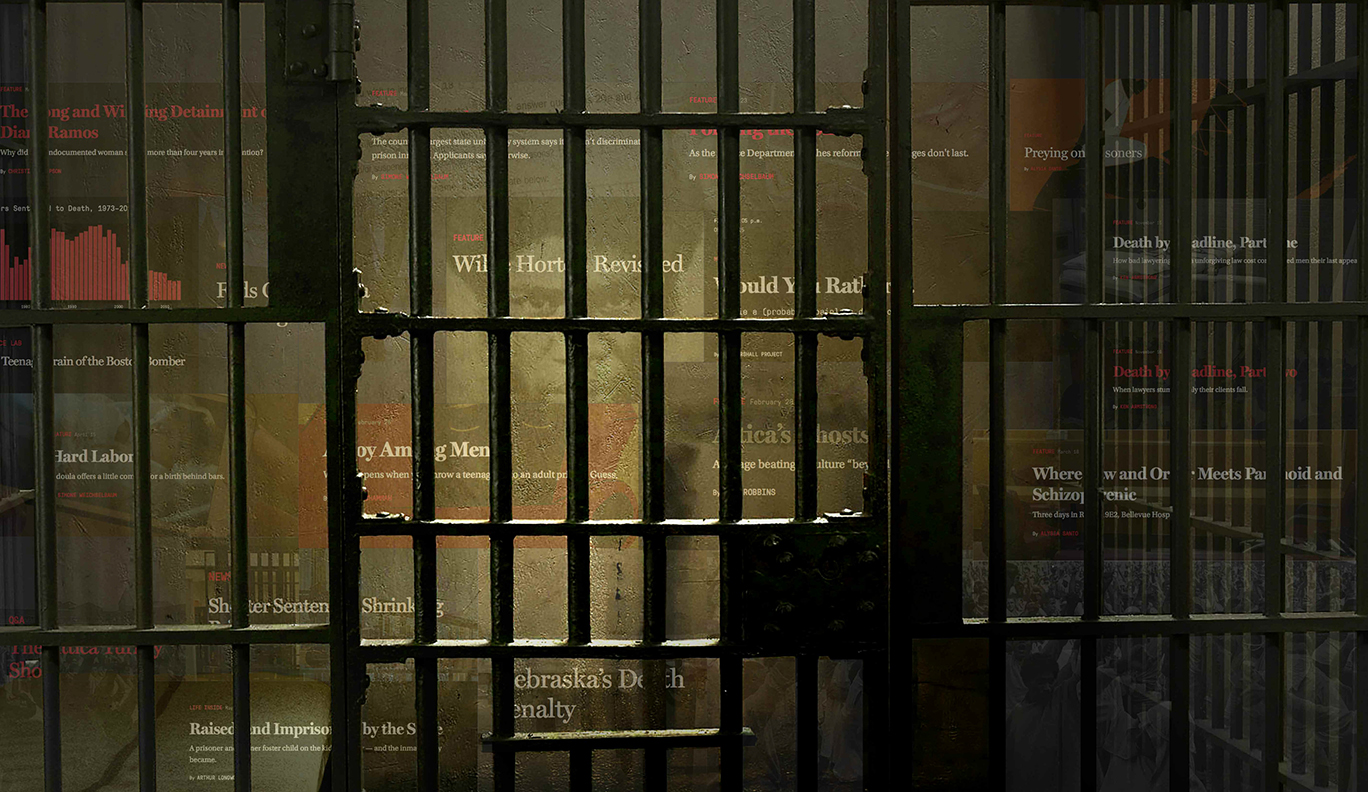

IT’S A CHILLY MARCH morning in Manhattan—the kind of grey, slushy Wednesday that can make even the most optimistic New Yorker wonder if winter will ever end. But for Bill Keller ’70, it might as well be spring.

IT’S A CHILLY MARCH morning in Manhattan—the kind of grey, slushy Wednesday that can make even the most optimistic New Yorker wonder if winter will ever end. But for Bill Keller ’70, it might as well be spring.