In April 1952, an unusual ad appeared in the classified section of the music and entertainment magazine Billboard. “Female impersonator magazine in preparation; articles and pictures needed from amateurs and professionals,” the ad read. It included an address in Long Beach, California, where readers could send their submissions.

A month later, a small set of subscribers received a 26-page, mimeographed magazine in the mail, called Transvestia: Journal of the American Society for Equality in Dress. The magazine was unlike anything else in circulation at the time. Transvestia self-consciously positioned itself as a publication by and for people who cross-dressed. “Perusal of this publication is primarily intended for complete as well as partial transvestites,” the first issue declared. Transvestia, the editors wrote, was designed so its readers could “obtain at least a modicum of mental security and adjustment” about their identities. Even Alfred Kinsey, the famed sexologist, wrote in to offer his support for the publication.

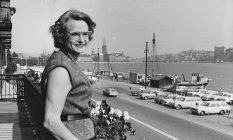

The small group of California women who co-founded Transvestia included a Pomona College graduate, Virginia Prince ’35, who helped launch the magazine alongside Joanne Thornton and the trans activist Louise Lawrence. Though Prince worked as a chemist at the time, she would eventually take over Transvestia and lead it through its decades-long run. Prince would go on to become one of the most prominent early activists in the trans community, publishing multiple books on her life and frequently appearing on television and radio shows in the 1960s and ’70s. But that foray into activism began, in many ways, with the 1952 magazine.

When the first issue of Transvestia appeared, the U.S. had little by way of a queer movement. An organization called the Mattachine Society had sprung up in 1950, but it was focused mainly on the needs of gay men. Aside from a few informal social groups, no organization existed for people who had a more varied experience of gender—meaning people who cross-dressed, people who lived as a gender other than the one they’d been assigned at birth, and so on. The term “transsexual,” a precursor to the modern label of “transgender,” was not coined in English until 1949.

Prince sparked a more nuanced conversation about gender identity in an era when that dialogue was almost entirely taboo, yet her legacy today remains complicated. Throughout her life, she rebuffed large swaths of trans people, dismissing those who opted for gender-affirmation surgeries as well as those who slept with members of the same sex. Anyone whose relationships would be seen as gay, she wanted to keep at a distance.

A complete collection of Transvestia magazine issues is held by the University of Victoria’s Transgender Archives.

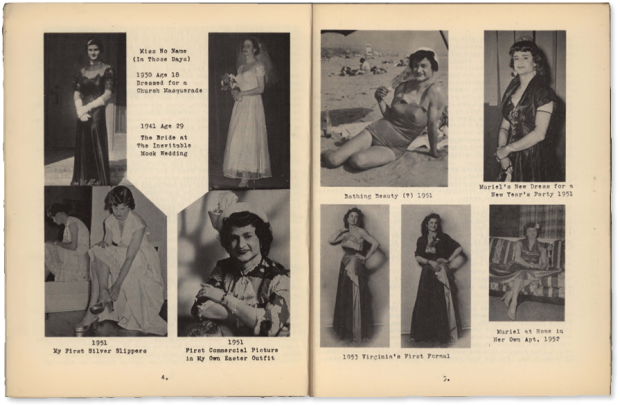

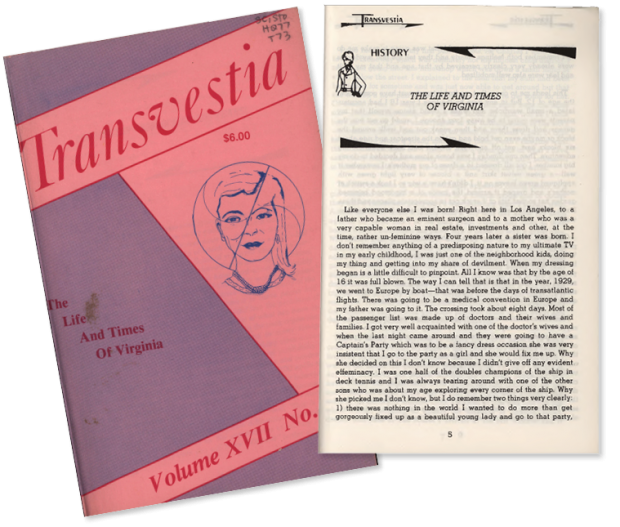

Prince was born in 1912 to a prominent Los Angeles family. Her father, Charles LeRoy Lowman, came from a long line of doctors. From birth, the world perceived Prince as a boy. But Prince quickly took a more nuanced view of her gender. Though she later pinpointed the beginning of her cross-dressing to when she was 12, Prince said she couldn’t remember all of the reasons she started wearing women’s clothes. “All I know was that by the age of 16 it was full blown,” she wrote in 1979 in the 100th issue of Transvestia, which can be found in the collection of the University of Victoria’s Transgender Archive. (A collection of Prince’s personal papers is archived at Cal State Northridge.) The teenager dressed mostly in stolen moments, saying that “by the time I was 18 I had accumulated a small wardrobe” of women’s clothes, “and when I could assure myself that my parents were going to be away long enough I would go into the garage and dress there and then sneak out.”

Prince enrolled at Pomona in 1931, joined a fraternity and dressed in coat and tie for class photos in the Metate yearbook. After graduating with a degree in chemistry, Prince—still going by the name Lowman—moved to San Francisco to pursue a Ph.D. in pharmacology. There, working as a medical researcher, Prince visited libraries across San Francisco in a professional capacity and on the side began combing through medical papers on trans people, eager to understand more about others who cross-dressed. At one point, Prince attended a psychiatric conference at which Barbara Ann Richards, a trans woman who received press coverage in 1941 after petitioning to have her name legally changed, described her relationship to gender. Prince was floored. Though the two had never met, Prince recognized Richards from their time at Pomona—the two had been in the same first-year class, both dressing as men at the time. Seeing Richards “had reached into my head where I kept all of my secrets and then revealed them to the world,” Prince said later. “I blushed deeply and became very nervous.” But Prince couldn’t get enough. “At the end of that session they announced that next week they would present another transvestite,” she wrote later. “Naturally you couldn’t have kept me away.”

In the early 1940s, Prince met Louise Lawrence, a trans organizer who was embarking on a speaking tour at medical schools across the country. Through Lawrence, Prince became connected with other people in the community. In the late 1940s, when Prince moved back to Southern California, she started meeting in a friend’s apartment with a small group of other people who were perceived as men but who lived, at least part-time, as women. That “ratty little place in Long Beach,” as Prince described it later, “became a mecca for all the TVs [transvestites] who knew about it.” Together, the women would create the first incarnation of Transvestia.

The original run of Transvestia fizzled out quickly, however. Only two editions were published in 1952. The third wouldn’t reach subscribers’ homes until May 1960. By that point, Prince was the magazine’s sole publisher and editor, a title that she held on top of her multiple business ventures.

A born entrepreneur, Prince launched a pet care wholesaler she called Cardinal Laboratories, which manufactured and sold beauty products to pet salons. Later, she created a chemical lab called Westwood Laboratories. The money she earned from the ventures helped subsidize her forays into activism. When Transvestia re-launched, Prince had only 25 subscribers, paying $4 each. The original co-founders were no longer involved in the publication. But Prince was determined to make it work.

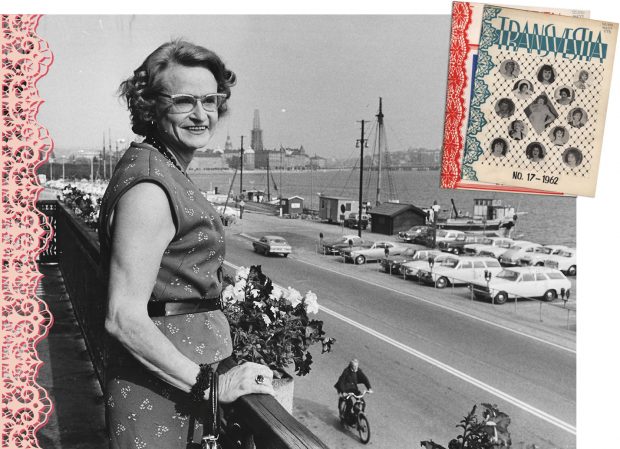

For those people who knew about it, Transvestia quickly became a lifeline. Not only did it feature advice on how to dress, how to talk to partners about gender, and how to find others in the community, but it also teemed with personal stories of people who gravitated toward genders other than the ones they’d been assigned at birth. The publication featured a rotating cast of “cover stars”—a group that either identified as femme cross-dressers or as trans women—who sent in photos of themselves, plus short essays describing their experiences. The cover star from Issue No. 8, an Australian woman named Kate Cummings, wrote of her gratitude to Transvestia. “When it arrived I was overwhelmed by the potential wealth of transvestite material available to me by subscribing,” she said.

Transvestia didn’t reach a wide audience. Prince once claimed it never surpassed 1,000 subscribers, and only a few newsstands seemed to stock it. Ms. Bob Davis, a longtime researcher and the founder of the Louise Lawrence Transgender Archive in Vallejo, California, said that she once saw issues of Transvestia on a stand at a leftist bookstore in Philadelphia. But few other retail stores stocked Transvestia.

Transvestia had other problems—namely, its membership restrictions. In the early days, Transvestia featured a broad spectrum of gender minorities. Cover stars would talk about sleeping with partners of multiple genders, and some of those underwent gender transitions of their own. But as the publication evolved, it became more restrictive.

In 1961, Prince created an organization of her own: First it was called the Hose & Heels Club, then Foundation for Personality Expression, then eventually Tri-Ess, for Society for the Second Self. Yet in all the organization’s incarnations, Prince limited membership to people like her: heterosexual-identified people who cross-dressed. Anyone else, including gay or bisexual people as well as any trans person who had undergone gender-affirmation surgery, was barred from joining. New members had to apply to be accepted, and on the group’s application, Prince asked questions about their sexual and surgical histories. (Tri-Ess still exists today, and its website identifies it specifically as a “group for heterosexual crossdressers.”)

Dallas Denny, a trans writer and activist, remembers writing a letter to Tri-Ess in the 1970s after seeing representatives from the group on TV. “I told them I understood I was not eligible to be a member but that I had been searching for community for my entire life unsuccessfully, and would you please put me in touch with someone who knows about transsexualism so I can get some support?” she says. A few weeks later, she received a handwritten letter from Virginia Prince, which ended up “explaining to me I could never be a female,” Denny says. “It just devastated me.”

Still, according to Davis, the Louise Lawrence archivist, some people who had undergone gender-affirmation surgeries did join Tri-Ess; they simply lied about their histories. In the 1970s especially, Prince’s organization was “pretty much the only game in town,” Davis says. “Certainly the only national organization and the one that was easiest to find information about.” Davis adds that, though other trans organizations existed at the time, they weren’t as large or well known—meaning some trans people had every reason to lie to get into Tri-Ess.

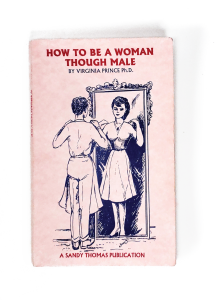

By the 1960s, Prince herself began living full-time as a woman, as she would continue to do until her death in 2009. She published a series of books, first The Transvestite and His Wife (1967) and then How To Be a Woman Though Male (1971), which doubled down on her opposition to gender-affirmation surgery. After Transvestia found some stability, Prince began bundling a selection of news about cross-dressing and gender identity in what she called her TV Clipsheet.

By the 1960s, Prince herself began living full-time as a woman, as she would continue to do until her death in 2009. She published a series of books, first The Transvestite and His Wife (1967) and then How To Be a Woman Though Male (1971), which doubled down on her opposition to gender-affirmation surgery. After Transvestia found some stability, Prince began bundling a selection of news about cross-dressing and gender identity in what she called her TV Clipsheet.

Even so, she kept her distance from trans people who opted for a surgical transition.

In 1959, Prince received a letter in the mail that would change her life. A pen pal sent her a photo of two women having sex with the caption “Me and You.” Prince replied with a detailed description of her own fantasies for the woman. Inspectors for the U.S. Postal Service, which at the time was actively prosecuting people who sent sexual content through the mail, flagged the letter. Weeks later, they showed up to the lab where Prince worked with an ultimatum: They wanted to charge her with obscenity, a federal crime, but they would drop it if she agreed to stop printing Transvestia. Prince refused. “She told him yes, she wrote that letter,” says Denny, who interviewed Prince in the 1990s. “They came back and arrested her in her place of business and led her out in handcuffs.”

Prince was charged with a felony. At trial in Los Angeles Superior Court in February 1961, Prince pled guilty to a smaller charge and was given five years of probation. Though prosecutors pressed to have the judge ban Transvestia altogether, Prince convinced the judge that the magazine wasn’t obscene.

“That gives me ambivalent feelings about her because, while she kept me out of the community for 10 years with her needlessly restrictive membership policies, she also took a big one for the community in not giving in to the postal authorities,” Denny says.

Prince, in that way, was a person of contradiction. Both her magazine and her organization made space for a more nuanced conversation about gender identity and presentation in the U.S. Prince stood up for people like her even when it meant facing the vicissitudes of the U.S. legal system, which was especially cruel to queer people. At the same time, Prince didn’t want to open up her new organization to a full spectrum of trans people.

“Virginia was the person who had a vision of expanding the community coast to coast, and indeed beyond,” Davis says, noting Prince’s influence in early trans groups in Europe.

Trans publications and zines didn’t explode in number until the 1980s and 1990s—until then, community members had to rely on only a miniscule subset of media to find others like them. Transvestia was usually the most prominent among them. That progress is more evident today, as trans people grace the cover of magazines like TIME and are the creators of TV shows like HBO’s Sort Of.

For all Transvestia’s flaws, “it brought so many people together,” Davis says. “It gave so many people the idea of, they’re not alone.” For Prince, too, it offered a path to embrace who she was. “In trying to help you, my readers, I have learned and grown myself,” she wrote in her farewell issue of Transvestia. After decades of activism, “I am now a whole person, completely self accepting and at ease.”

Connect with The Scooty Fund

Connect with The Scooty Fund

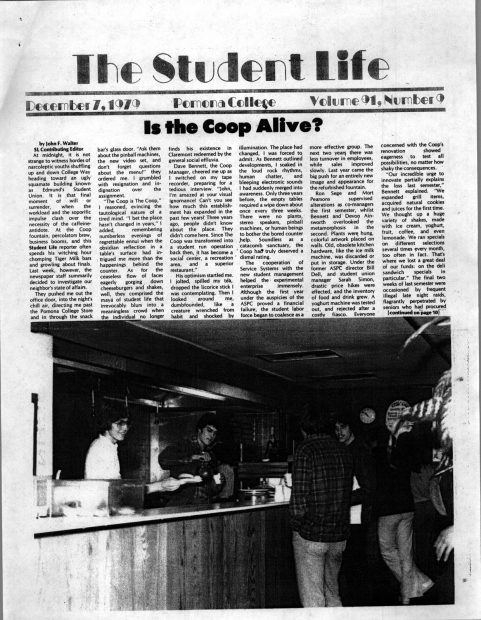

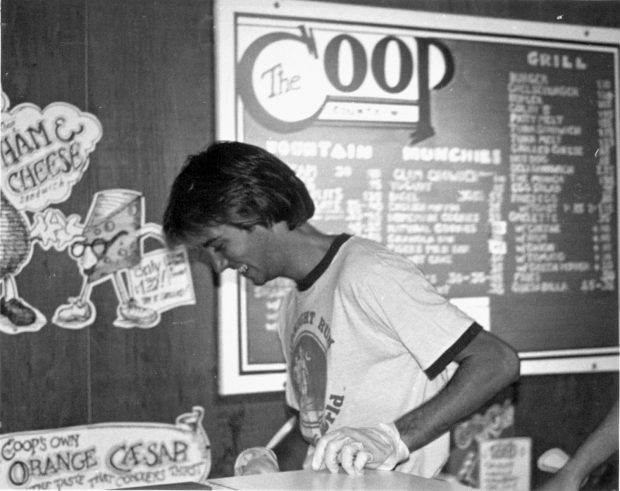

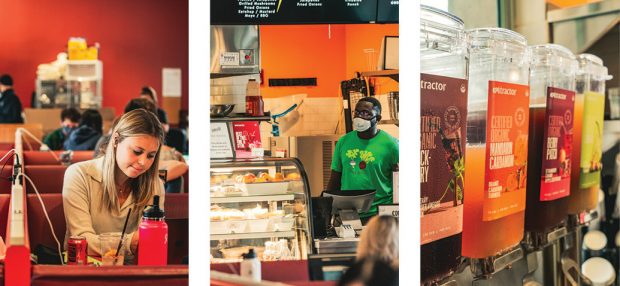

Apparently, those hopes weren’t realized. In 1979, The Student Life published an article with the headline, “Is the Coop Alive?” According to the article, three years prior, “people didn’t know about the place,” “the empty tables required a wipe down about once every three weeks” and it was “soundless as a catacomb sanctuary.”

Apparently, those hopes weren’t realized. In 1979, The Student Life published an article with the headline, “Is the Coop Alive?” According to the article, three years prior, “people didn’t know about the place,” “the empty tables required a wipe down about once every three weeks” and it was “soundless as a catacomb sanctuary.”

1. Grow up in New York City and develop an unexpected appreciation of bugs—and not the computer programming type. “Even as a child, I just loved being outside. I loved turning over rocks,” says Rodriguez, who has a deep affection not only for insects but also for animals and the outdoors.

1. Grow up in New York City and develop an unexpected appreciation of bugs—and not the computer programming type. “Even as a child, I just loved being outside. I loved turning over rocks,” says Rodriguez, who has a deep affection not only for insects but also for animals and the outdoors.

Horse Brain, Human Brain

Horse Brain, Human Brain My Daily Actions, or The Meteorites

My Daily Actions, or The Meteorites Leavetakings

Leavetakings Mountain Climber

Mountain Climber ASPC Manual of Preventive Cardiology

ASPC Manual of Preventive Cardiology  Not About Dinosaurs

Not About Dinosaurs Survive

Survive Posthuman Bliss?

Posthuman Bliss? The City and the Wilderness

The City and the Wilderness The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener:

The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener: