![The [Basketball] World According to Voigt](https://magazine.pomona.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/OtherFeature1-Voigt-140x140.jpg)

Click click click. Videotape is the focus of Will Voigt’s first job after his 1998 Pomona graduation—collecting it and editing it for the San Antonio Spurs. He is a peon in the kingdom of professional basketball coaching, his only power the dicing and splicing of game tape. Start, stop, rewind, pause, fast-forward—the VCR controls are squares, triangles and hash marks, some of the same symbols coaches use to communicate basketball plays.

Click click click. Videotape is the focus of Will Voigt’s first job after his 1998 Pomona graduation—collecting it and editing it for the San Antonio Spurs. He is a peon in the kingdom of professional basketball coaching, his only power the dicing and splicing of game tape. Start, stop, rewind, pause, fast-forward—the VCR controls are squares, triangles and hash marks, some of the same symbols coaches use to communicate basketball plays.

That basic code of basketball is something Voigt knows well from competing for his tiny Vermont high school three hours north of the gym where James Naismith invented the sport with peach baskets as goals. In the NBA org chart, the assistant video coordinator is barely listed, but in Voigt’s case, it gives him a seat on the bench where Pomona-grown head coach Gregg Popovich and assistant Mike Budenholzer ’92 held court.

The Spurs gig didn’t turn into a trailer for his own version of Hoosiers. He didn’t move up and around the NBA. Instead, Voigt’s own education and mastery of basketball coaching would be a peculiar string he kept unspooling, to Norway, back to Vermont, California, China, Angola, and even the 2016 Rio Olympics with the Nigerian national team. He’s bounced from continent to continent, most recently landing in Germany at the height of the pandemic to coach the Telekom Baskets Bonn in the Basketball Bundesliga.

If you lose track of where in the world Will Voigt is coaching, you can usually find him on YouTube, sharing the artful ways basketball is played far from the NBA. Now he’s starring in videos instead of taping others, and friends and strangers are watching, backing up, clipping, studying. Trying to get an edge from Will Voigt.

“Will is a little wacky, and his story has played out that way,” said Budenholzer, now head coach of the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks. “In San Antonio, he was there anytime for anyone who needed anything, because everyone mattered, from the bottom of the ladder as a video guy to the top. Everyone contributes whatever is needed to the team’s growth. Young coaches can be fascinated with the NBA, but there are only so many teams and jobs, so you have to be willing to go anywhere. Will is the greatest example of taking that advice to new places that are almost unheard of in the NBA.”

Tipoff

Everyone matters in unincorporated Cabot, Vermont.

When Voigt was 5, voters in the city of Burlington, 60 miles west, elected a new mayor named Bernie Sanders. The most famous export is the cows’ milk that’s used to make Cabot cheese, which comes from a local co-op. In 2019, the population was 189. “Indomitable people,” Calvin Coolidge said of Vermonters, “who almost beggared themselves to serve others.”

Voigt practiced shooting to a goal in his family’s barn, where birds would build nests between the net and backboard when Voigt went into soccer and baseball seasons. Every athlete who could play, did. Voigt, a point guard, led his team through state playoffs against Vermont’s smallest schools and graduated valedictorian in a class of 18. He also played piano because his mother, Ellen, who had served as Vermont’s state poet, and his dad, Francis, who had started the New England Culinary Institute, insisted he do something besides sports. When it came to his college, they insisted on strong liberal arts. “They would not budge,” Voigt recalls.

Due east, over the White Mountains and into Maine, is the town that Bill Swartz had left to become head soccer coach at Pomona-Pitzer. When Voigt reached out, Swartz recalled thinking, “I can definitely take a chance on this guy. I’ve always thought that players from those New England states had qualities that were difficult to put on paper. Will had a good sense of who he was and how he fit in.”

With Voigt as a backup forward on the soccer team, the Sagehens won the 1996 Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference. With less fanfare but more foreshadowing, Voigt performed in a mock Congress with Claremont McKenna students, playing independent-minded Vermont Senator Jim Jeffords. “Will was a swing vote, in the middle of everything, talking to both sides and paying attention to everything,” noted Professor of Politics David Menefee-Libey. “It makes sense that he’d become a coach.” Voigt didn’t see it then. When he graduated in 1998 in political science, he expected to go to law school and become a sports agent. Basketball was calling.

First half

Earlier in the century, the sunny beaches of Los Angeles had inspired tire retreader William J. Voit to invent an inflatable rubber ball. He vulcanized it to create the modern basketball. The summer after college, Will Voigt bounced into the Long Beach State Pyramid for the NBA free agent league. He hoped to hang with agents, and one asked Voigt to coach a team led by Duke’s Ricky Price. “The players were trying to shine and show teams what they could do, and Will took it so seriously,” Price said. “He even put in a defense—for a summer league? I thought he was auditioning for a coaching spot for real.” This—plus an internship with the Los Angeles Clippers and Pomona ties—helped him get to the San Antonio Spurs’ sideline.

Earlier in the century, the sunny beaches of Los Angeles had inspired tire retreader William J. Voit to invent an inflatable rubber ball. He vulcanized it to create the modern basketball. The summer after college, Will Voigt bounced into the Long Beach State Pyramid for the NBA free agent league. He hoped to hang with agents, and one asked Voigt to coach a team led by Duke’s Ricky Price. “The players were trying to shine and show teams what they could do, and Will took it so seriously,” Price said. “He even put in a defense—for a summer league? I thought he was auditioning for a coaching spot for real.” This—plus an internship with the Los Angeles Clippers and Pomona ties—helped him get to the San Antonio Spurs’ sideline.

“Good or bad, I have had a confidence in myself that is generally unjustified,” Voigt said. “Like I have never been afraid of the moment. That helped me in San Antonio, being able to keep it real. I could be myself. If I stopped and thought about being a small-time Vermont kid on the NBA court with one of the best coaches in the history of the game, I would be paralyzed.”

Voigt had ventured into college basketball coaching when a voice from his past opened an unexpected door. His high school coach Steve Pratt, in Chicago to train players for college and the NBA draft, was asked if he knew anyone who could coach a pro team in Norway immediately. Its American coach had decided not to show. “I have the guy,” Pratt said.

Halftime

To say that Voigt, then 27, brought passion to the Ulriken Eagles is incomplete. He also loves arguing. In Oslo, the Eagles were down 26 points to the league’s best team when Voigt got ejected right before halftime. Pratt was visiting, and heard Voigt’s last words to his team: “Screw this! You have nothing to lose. Just go beat their ass!” And they did.

Second half

A vote brought Voigt back to Vermont, when he was elected coach of the Vermont Frost Heaves, a startup in the American Basketball Association. Yes, elected by Vermonters given ballots by team owner and Sports Illustrated writer Alexander Wolff. “Wouldn’t it be great to have someone who was deep into hoop and who can see the larger world out there?” Wolff wondered. The Frost Heaves won two straight ABA championships, which had only been done before once, by the Indiana Pacers.

A vote brought Voigt back to Vermont, when he was elected coach of the Vermont Frost Heaves, a startup in the American Basketball Association. Yes, elected by Vermonters given ballots by team owner and Sports Illustrated writer Alexander Wolff. “Wouldn’t it be great to have someone who was deep into hoop and who can see the larger world out there?” Wolff wondered. The Frost Heaves won two straight ABA championships, which had only been done before once, by the Indiana Pacers.

“My first impression of Will? I got a knock on my door at the Ho Hum Motel in Burlington, and God knows who was going to show up,” said John Bryant, a signee who had just flown in from China, now an assistant coach with the Chicago Bulls. “Will didn’t even look like a player much less a coach. He has that baby face. He couldn’t be the right guy, but he was.” Voigt moved on to five years with the Bakersfield Jam in the NBA D-League, where he left a memorable impression on his team’s Nigerian-American players. When the Nigeria Basketball Federation needed a coach, it picked Voigt, who had just wrapped a gig with the Shanxi Dragons of the Chinese Basketball Association. Voigt coached the Nigerians to the African title and one of only a dozen spots in the 2016 Rio Olympics. Despite winning only one game in Rio, Voigt had sealed his reputation, and the next team to sign him was Nigeria’s fierce rival Angola. In Luanda in 2018, Angola was practicing in the Estadio da Cidadela when a large light fixture fell from the ceiling, barely missing Voigt and nearby players. “At that stage, I had been in Africa so long, that didn’t faze me as much as it should have,” Voigt said.

He tweeted the near-miss with video footage. Just like in San Antonio, the cameras were rolling in Luanda, too. But now Voigt was becoming a more seasoned coach in a setting that was less star-driven, more Cabot-like. Even the international basketball court, at 28 by 15 meters, is slightly smaller. “More ball movement, more people movement,” said Budenholzer. “We all try to do similar things as coaches, but the international coaches and teams buy into it more, and when everybody is touching the ball and moving, it is a more inclusive way of playing.”

African players taught Voigt an intuitive defense that fascinated him. Defending players typically must react in seamless actions when the other team drives to the basket: cover their player, help defend against the ballhandler, rotate to help other defenders, and then recover to their assigned player. The Africans simplified this. When the ballhandler beat the primary defender, the next defender rotated into that gap, leaving a gap that the next defender filled.

Voigt calls this defense the peel switch. “Most of the teams I coach have to be different to find a competitive edge, so when I saw this, I knew it was something different that would help us play to our strengths,” Voigt said. “Teams that do this are really good at communicating, and I liked exploring something new like this rather than doing what we always do.”

Last year, when the pandemic created a gap in his chances to coach, Voigt did a peel switch of his own, turning to teaching this and other basketball strategies online until he got the call from Telekom Baskets Bonn.

Final score

Voigt is now 44, and when he looks back on his vagabond career—the video highlights, if you will—Pomona’s liberal arts training shows in his open-mindedness, critical thinking, engagement in the larger world and appreciation for multiple perspectives. He left campus at the end of one century to embrace a rapidly changing world while hopscotching between rectangular hardwood landing pads. He speaks six languages.

“If you look at all the places I’ve been, it’s hard to imagine any plan that would have taken me on that route,” he said. “I think everyone aspires to be and do what they can at the highest level, and for me that was to be an NBA coach one day. But when you get locked into that, as soon as you go somewhere, you are trying to get somewhere else. You won’t enjoy yourself, and you won’t give everything you have. I’ve embraced jumping on opportunities when they’ve presented themselves and doing it ‘all in’ and seeing what that leads to next.”

The Voigt video is still rolling, so stay tuned for the next episodes, wherever they’ll be filmed.

Learn a few basic guitar chords from a Scout leader as a Cub Scout in Brussels, Belgium. Get your own guitar for your birthday, and take lessons from a high school student. Ask your parents to have the family piano tuned so you can practice chords.

Learn a few basic guitar chords from a Scout leader as a Cub Scout in Brussels, Belgium. Get your own guitar for your birthday, and take lessons from a high school student. Ask your parents to have the family piano tuned so you can practice chords. Start your own band—named Rhapsody for the famous song by Queen—at age 16. Play for the fun of it, but more importantly, to get the attention of girls. Sing in English despite having only an elementary grasp of the language.

Start your own band—named Rhapsody for the famous song by Queen—at age 16. Play for the fun of it, but more importantly, to get the attention of girls. Sing in English despite having only an elementary grasp of the language. Write your first song in high school. In college, form a better band—named (inexplicably) The Ice Creams. Go to lots of rock concerts by bands like The Police and UB40, and play more than 50 gigs, once as the opener for a Tom Robinson concert.

Write your first song in high school. In college, form a better band—named (inexplicably) The Ice Creams. Go to lots of rock concerts by bands like The Police and UB40, and play more than 50 gigs, once as the opener for a Tom Robinson concert. Cut your first and only record at age 20 on a local label and see your music video appear—once—on Belgian TV. As your interest in African politics takes precedence, dissolve the band and drop music almost entirely for the next dozen years or so.

Cut your first and only record at age 20 on a local label and see your music video appear—once—on Belgian TV. As your interest in African politics takes precedence, dissolve the band and drop music almost entirely for the next dozen years or so. Buy an electric piano with your first paycheck from the World Bank in 1988. Use it sparingly until the mid-1990s, when you resume songwriting as a creative outlet while working on your dissertation. Get an 8-track recorder and sound-engineer your own songs, one track at a time.

Buy an electric piano with your first paycheck from the World Bank in 1988. Use it sparingly until the mid-1990s, when you resume songwriting as a creative outlet while working on your dissertation. Get an 8-track recorder and sound-engineer your own songs, one track at a time. Write a few new songs, including one for your wife titled “When You Shave Your Legs.” After getting your Ph.D., lose yourself in work. Store your instruments under the bed, where they will mostly gather dust for more than 20 years.

Write a few new songs, including one for your wife titled “When You Shave Your Legs.” After getting your Ph.D., lose yourself in work. Store your instruments under the bed, where they will mostly gather dust for more than 20 years. Notice a flyer for guitar lessons while on sabbatical in 2018. Decide to expand your musical chops by taking guitar lessons. Then take it a step farther by auditing music classes with Pomona professors Tom Flaherty and Eric Lindholm.

Notice a flyer for guitar lessons while on sabbatical in 2018. Decide to expand your musical chops by taking guitar lessons. Then take it a step farther by auditing music classes with Pomona professors Tom Flaherty and Eric Lindholm. Start writing songs again, using software called Guitar Pro. Then with another program called Logic, build them out a track at a time. Send the “pre-mix” to a studio in Los Angeles to be professionally mastered.

Start writing songs again, using software called Guitar Pro. Then with another program called Logic, build them out a track at a time. Send the “pre-mix” to a studio in Los Angeles to be professionally mastered. Under the moniker “Not a Moment Too Soon,” produce your first album, titled “Back to Plan A.” Post it on SoundCloud. Then sign up with a distributor to post your tracks on a range of platforms, from Apple Music to Spotify.

Under the moniker “Not a Moment Too Soon,” produce your first album, titled “Back to Plan A.” Post it on SoundCloud. Then sign up with a distributor to post your tracks on a range of platforms, from Apple Music to Spotify. Post your second album—titled “Well,”(including the comma)—with cover art by Pomona student Sei M’pfunya. Plan to keep sharing your songs as long as you find it rewarding and the songs give people joy.

Post your second album—titled “Well,”(including the comma)—with cover art by Pomona student Sei M’pfunya. Plan to keep sharing your songs as long as you find it rewarding and the songs give people joy. Both of Englebert’s albums are available free at his website:

Both of Englebert’s albums are available free at his website:

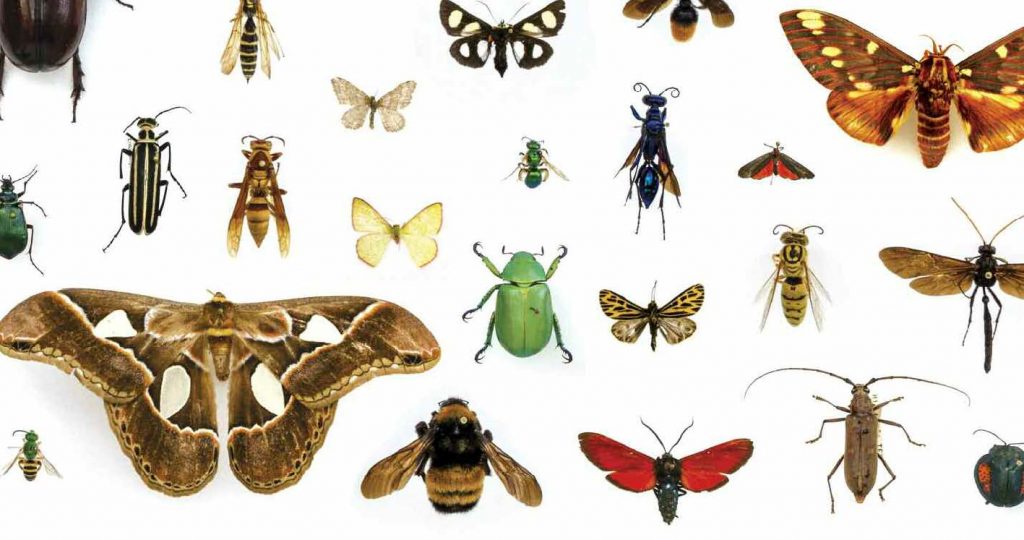

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era.

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era. As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant.

As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant. In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.

In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.

My favorite anecdote about growing up in the rural South is a childhood memory of sitting with my aunt and uncle at their red Formica kitchen table, which was strategically positioned in front of a double window looking out on the dirt road in front of their house. Each time a car or—more likely—a pickup would go by, leaving its plume of dust hanging in the air, both of them would stop whatever they were doing and crane their necks. Then one of them would offer an offhand comment like: “Looks like Ed and Georgia finally traded in that old Ford of theirs. It’s about time.” Or: “There’s that Johnson fellow who’s logging the Benton place. Wonder if he’s any kin to Dave Johnson.”

My favorite anecdote about growing up in the rural South is a childhood memory of sitting with my aunt and uncle at their red Formica kitchen table, which was strategically positioned in front of a double window looking out on the dirt road in front of their house. Each time a car or—more likely—a pickup would go by, leaving its plume of dust hanging in the air, both of them would stop whatever they were doing and crane their necks. Then one of them would offer an offhand comment like: “Looks like Ed and Georgia finally traded in that old Ford of theirs. It’s about time.” Or: “There’s that Johnson fellow who’s logging the Benton place. Wonder if he’s any kin to Dave Johnson.”