You want to serve your country. You aspire to run for office—and not just any office. You want to be president of the United States. If you succeed, you will control the most advanced technology ever conceived, much of it secret. You will be able to authorize missile strikes, negotiate treaties, and spy on people around the world. And with a vast payroll, you will now run the largest employer in the country—the federal government.

For a moment, say that you win. You might hope to use this power to achieve great things such as ending poverty, providing affordable health care, or eliminating violent crime. You will have the ability to influence legislation and shape decisions about how to use the enormous federal budget. Lives, jobs, and trillions of dollars hang in the balance—and you have the ability to tip it. As you wave to your inauguration crowd through a blizzard of confetti, nothing seems out of reach.

Be careful: History might judge your presidency harshly. You don’t want to be lumped in with Andrew Johnson, a president who opposed and undermined the core values of the country. Surveys of historians from 2002 and 2010 each ranked Johnson as one of the worst presidents in American history. He was impeached by the House of Representatives (but not removed from office by the Senate) for firing his secretary of war Edwin Stanton, an ally of many in Congress at the time. Far worse, he fiercely opposed the Fourteenth Amendment—the monumental civil rights achievement of Congress after the Civil War. The amendment guaranteed equal protection of the law and extended citizenship to African Americans and all people born or naturalized in the United States. That amendment was necessary in part because Johnson essentially refused to execute the Thirteenth Amendment, which banned slavery—a violation of his sworn duty to carry out the law of the land.

On the other hand, Abraham Lincoln, who directly preceded Johnson, is seen as one of our greatest presidents. Among his many achievements, he kept the country together by winning the Civil War and shepherded the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. Why was Lincoln able to be so great? He had a diligent fascination with the Constitution, the core principles that upheld the nation and the presidency, and the history of the Framers (the collective term we use for the storied people who crafted the Constitution, such as James Madison and Alexander Hamilton). As the political theorist George Kateb writes, “Lincoln revered the principle of human equality and believed that he therefore should revere the US Constitution, the system of government created under it … making real the abstract principle of human equality.” For Lincoln, that meant standing up for the fundamental values of the oath and the Constitution while working within the constraints that limited his office. To end the evil of slavery nationwide, he didn’t rule by dictate; instead, he used the Constitution’s legal procedure to pass an amendment accomplishing his goal. Lincoln was a great president because he understood how the office of the presidency—used as the Framers had created it—could preserve, protect, and defend constitutional values.

As we shall see, the oath requires that the president uphold the Constitution—even parts with which he or she disagrees. If you fail to do so, you’ll end up with Johnson on the list of worst presidents. If you succeed, you can be remembered with Lincoln among the greats.

All presidents, from George Washington to Donald Trump, began their terms with dreams of accomplishing great things. But whether your presidency is monumental or disastrous will hinge largely on a simple thing: that you, a future president, understand how the responsibilities of the Constitution apply to your job.

***

What do you need to know to be president? Most of all, you need to know the U.S. Constitution. As president, your first task is to recite the oath of office. You’ll stand in front of your inauguration crowd, guided by the chief justice of the Supreme Court, and recite the following words: “I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of the President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

This oath is your public contract with the American people, and reciting it is your first constitutional responsibility. Before you recite it, you must know what it means and where it comes from. The oath is found in Article II of the Constitution, which established the presidency and defined its powers and limits. Ratified in 1788 and amended three years later in 1791 with a Bill of Rights, the Constitution contains a series of principles that limit the power of all federal officials, including the president, and defines the powers that those officials do have. The Constitution will serve as your blueprint for how to do the president’s job, helping you to anticipate the pitfalls that all presidents should avoid.

The oath itself is a reminder that your powers are conditionally granted and come with limits. The Constitution, in literally dictating your first instant in office, signals clearly that you are not free to act however you wish. Article II goes on to provide directions for what you must do and avoid. The oath is thus not merely a ritual—it is a recognition that you temporarily occupy an immensely powerful office, and that you must internalize the demands and responsibilities that come with it. Notice that you are promising to “preserve, protect and defend” the Constitution—not just to avoid violating it. In pledging to “faithfully execute” the office of the president, you promise to put aside your private interests to occupy a public and limited role on behalf of the American people. If you are not willing to work within these limits and take initiative to promote the document, the Oval Office isn’t for you.

It was George Washington’s second inaugural address—which at 135 words remains the shortest in history—that gave voice to the ideas underlying the oath and the office. Today, we tend to think of inaugurations as grand affairs, with modern presidents using them to draw widespread attention to their agendas. But Washington’s 1793 inauguration was much more subdued—fitting, since his address emphasized the limits of the presidential office. He held the inaugural ceremony in the relatively modest Senate Chamber of Congress Hall, located just steps from Independence Hall, where he had presided over the Constitutional Convention six years earlier. This choice of venue signified his respect for the legislative branch as a coequal to his own executive branch. In his speech, Washington challenged Americans to stop him should he fail to live up to his duties:

Previous to the execution of any official act of the President, the Constitution requires an oath of office. This oath I am now about to take, and in your presence: That if it shall be found during my administration of the Government I have in any instance violated willingly or knowingly the injunctions thereof, I may (besides incurring constitutional punishment) be subject to the upbraidings of all who are now witnesses of the present solemn ceremony.

In emphasizing the solemnity of the oath, Washington here was speaking to future presidents and the future Americans charged with holding them accountable. Washington is asking you, a future president, to respect the obligations and the limits of your new office. And to those of us who won’t be president, Washington is reminding us that we, too, must ensure that a president carries out the duties of the office.

Washington’s words here provide the impetus for our focus on what the Constitution demands of a president. This guide will detail what you need to know—how to take the oath seriously, and how to understand both the obligations and the limits that it places on you. It is not enough merely to avoid constitutional punishment, although that punishment—in the form of impeachment, censure, or losing an election—is still something you should worry about. You should go beyond this bare minimum requirement of the office, and defend the values that the Constitution enshrines. Unlike President Johnson, and like President Lincoln, you must recognize what the Constitution requires: read it, study it, and through your speech and actions, promote it.

It’s crucial that you see the Constitution’s rules as legitimate constraints, not obstacles to get around. But the Constitution is more than just these rules: it stands for a wider morality of limited government and respect for people’s rights. You must find a way for your actions and words to honor and expound those values, while abiding by the limits that your office places upon you. You might be tempted to see the Supreme Court as the sole authority to tell you when you’ve strayed from constitutional values. Sometimes, it does play this role: courts have often limited the president by declaring his actions unconstitutional. But as you will see, the court’s role in American history has often been limited. The Supreme Court has sometimes protected civil liberties that presidents have put under threat, but at other times it has failed to do so. As president, you have an obligation to go beyond what courts require of you, taking it upon yourself to defend the principles and rules of the Constitution. In order to do that, you must first understand what those principles and rules are.

***

As a professor of constitutional law, my job is to introduce students to the core tenets of the Constitution. My students are often amazed by the scope and foresight of this document. It does more than create our entire system of government. It also provides tools that can limit those who try to abuse that system to violate the rights of the people.

The Constitution creates and defines the duties of the three branches of government: legislative, judicial, and executive—the last of which contains the office of the presidency. The Constitution strictly limits the president’s powers in Article II, but it also limits the president in other creative ways: by granting certain powers to the other two branches, letting states retain certain privileges, and enshrining the rights of the people. Each of the three branches interprets the Constitution and encourages the others to act in ways that are consistent with its requirements.

This includes you, no matter where you live or what you do. The Constitution is not magically self-enforcing, and there is no “Constitution police.” Not even the Supreme Court will always succeed in defending the Constitution’s values and enforcing the proper limits it places on you. Fortunately, you will not be alone in defending the Constitution. In the end, it is essential for all citizens to recognize that there is no guarantee that presidents or courts respect the Constitution. By demanding that elected representatives—whether senators or town council members—read, understand, and comply with the Constitution, the people can make sure that the requirements of the Constitution do not become, as Madison worried, mere “parchment barriers.” Ultimately, the president is checked not by the Constitution itself, but by the American people demanding that it be respected.

To uphold this duty, though, you need to understand the principles of the Constitution for yourself. Together, we’ll be taking a deep dive into our country’s founding document.

***

The Constitution isn’t the first thing most people think about when they vote for a presidential candidate. My own interest in politics certainly didn’t start with the Constitution.

When I was growing up in Queens, my father worked for a local politician. I sometimes tagged along for political events. And in Queens, the political event of the year was the Queens Day Celebration—a parade that transformed Flushing Meadows Park, a faded gem that had twice held the World’s Fair, into the center of the world—in my young eyes, at least. It was the sort of grand event that all the major figures from Queens would attend—and perhaps among them, a certain future president. It was there, at age nine, that I first saw my boyhood hero at the front of the parade: Edward Koch, the mayor of New York City.

At the time, Koch was larger than life. Some even mused that he might become the first Jewish president. Now I was walking directly behind him, right under Koch’s enormous arms, which he threw open every few seconds as he bellowed to the crowd, “How am I doin’?” The crowd of onlookers screamed their approval.

Just then, Koch whispered to a local politician next to him, “I’d love some ice cream. Vanilla.” The politician turned behind, pointed to a man next to me, and snapped, “Get the mayor some ice cream. Vanilla!” The aide turned and sprinted across the field next to the parade route, and returned about ten minutes later with a vanilla ice cream cone.

That was the day I decided I wanted to be mayor. To the mind of a nine-year-old boy, being mayor meant having the power to seemingly get anything—even ice cream—and get it on demand. w

What can a nine-year-old boy intuit about politics? A lot, actually. For many adults, it’s moments just like these that draw them to politics in the first place. For them, the presidency is shorthand for fame and power. They want to live in the White House. They want access to the staff. The helicopters. Air Force One.

When they wrote the Constitution, the Framers were well aware of the trappings of power. That is why the Constitution’s oath is meant to take a private citizen, whose focus lies with his or her own beliefs and desires—whether ice cream or the nuclear football—and transform that person into a public “officeholder,” whose job is to safeguard the Constitution and the country it governs. Presidents, of course, are required to recite the oath. But reciting it is not enough; they should read the oath carefully, internalizing its fundamental principles and the constraints it creates on the office. When you’ve just been elected by millions of people, you might feel as if you’re authorized to do as you wish—or whatever your supporters want you to do. But the constraints on your office are critically important. In fact, they are a defining feature of our system of government.

***

In this guide, we will examine the difficult balance between respecting the wishes of the people who elected you and respecting the limits the Constitution places on your power. These limits constrain presidents who cater to the worst prejudices of the people who elected them. But such safeguards, which operate by slowing down the pace of government, can also contribute to government gridlock.

President Harry Truman observed this conundrum firsthand. In 1952, as he was preparing to leave office, Truman turned to an aide and predicted what would happen to his successor, former general Dwight Eisenhower, who was accustomed to the military’s famous efficiency. “He’ll sit here and he’ll say, ‘Do this! Do that!’ And nothing will happen,” Truman mused. “Poor Ike.”

Truman’s words indicate a central irony of the American presidency: yes, the office is immensely powerful. Yet it is so often constrained and thwarted—by Congress, the courts, the press, the states, ordinary citizens, and even by its own executive bureaucracy. This limited role in the constitutional system is no doubt frustrating for presidents, but it serves the wider goal of the Framers: respecting individual rights and the rule of law—the notion that we are not governed by individuals’ whims but by standards common to all. The constraints are a feature, not a bug. They ensure that the oath is not a set of mere words, but that there are mechanisms for constraining a president.

The “Poor Ike” story is often told by scholars of the presidency. It was reported in Richard Neustadt’s influential book Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents. Neustadt’s book taught future presidents and their aides how to use the power of persuasion to lead the country. With its focus on power, the book was so popular in the 1960s that President Richard Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, made it required reading for all staffers in the White House. Later, as we’ll see, after Nixon was impeached for his role in the break-in at the Watergate Hotel and the subsequent cover-up of the event, one Nixon staffer told Neustadt that “you have to share the responsibility” for the illegal actions because of the ideas in his book.

Neustadt took this accusation seriously. He had learned to understand the Constitution when he was a student in civics class and assumed that his readers had done the same. But during Watergate, he realized that the decline of civics education meant that Nixon’s staffers had not developed an appreciation for the limits of the Constitution, instead focusing more on presidential power. Our guide makes clear what Neustadt’s book did not: that the Constitution is not a mere obstacle to get around, and trying to do so would be a disservice to the Framers’ ideas. To understand the Constitution, you need to see that the powers it grants are of a particular kind—loaded with tripwires, trapdoors, and springboards that protect the rights of the people and the rule of law. Presidents should celebrate, not bemoan, this complex design.

The best guide we have to the Constitution is the Federalist Papers. Written anonymously during the course of a single year between 1787 and 1788, the Federalist Papers were the project of three Framers—James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay—and were an effort to persuade New York and other states to ratify the Constitution. Like many of their fellow Framers, Madison, Hamilton, and Jay were concerned about the tyranny of Great Britain, against which they had just revolted. As a result, the Federalist Papers focused a great deal on how the governmental structure outlined in the Constitution would protect citizens from a flawed government—including a despotic president. They emphasized what it meant to be a legitimate leader.

James Madison, an author of the Federalist Papers and a primary writer of the Constitution, will serve as our guide throughout this book. Madison is a good guide in large part because he was the Framer who most consistently stressed the limits on the president, writing, “the ultimate authority … resides in the people alone.” He was also the most influential proponent of a Bill of Rights. And as president, Madison went beyond what he believed he was required to do by the courts, using his own veto power to strike down laws he viewed as violations against the Constitution. This guide may not always agree with Madison: for instance, in matters concerning hiring and firing, where he wrongly ascribed too much power to a president. But overall, it is Madison’s vision of a limited presidency that inspires the ideas of this book.

Madison’s vision of the presidency was just one of many debated at the time. Another Framer, Alexander Hamilton, stood for a markedly different vision. These days, Hamilton, a famous delegate to the Constitutional Convention from New York who later became secretary of the treasury, receives a good deal more popular attention than his fellow Framers. (Let’s just say there is no Madison: The Musical.) At times, Hamilton was Madison’s ally—recall that they wrote the Federalist Papers together. But they often clashed, especially on where presidential limits ought to lie.

Hamilton referred to the need for “energy in the executive,” by which he meant the president’s ability to make great things happen quickly. In a Hamiltonian view, the president is not a king—but does retain some kinglike powers. He argued that the president should have broad powers in war and foreign policy, even though the Constitution didn’t say so explicitly. Madison disagreed. These debates still resonate long after the Founding. For example, some legal precedent has suggested that the president is not required to uphold the equal protection of the laws in certain areas, such as immigration. Other thinkers have suggested the Constitution’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” may not prevent the president from using or sanctioning torture. President Nixon even famously claimed the president couldn’t be indicted while in office. However, with Madison as our guide, we will push back against this strain of Hamiltonian constitutional thinking that emphasizes the powers of the president over the constraints on the office.

A president who takes the oath seriously needs to consider these Framers’ competing visions. But the Framers aren’t the only thing that needs to be considered: the president also needs to consider the text of the document, case law, and the meaning of later amendments such as the Fourteenth Amendment and its Equal Protection Clause. The Framers’ ideas should be honored—particularly Madison’s vision of a limited presidency—but only as a guide, not as the final word on what the Constitution means.

Madison designed the Constitution to ensure that those of us who will not be president—“the people”—could protect the office from a president who failed to carry out the oath. He and the Framers gave us a Bill of Rights and institutions such as the judiciary, the Congress, and state governments to protect those rights if a president failed to do so.

In modern-day politics, we often try to understand what “We the People” want through polls and policy preferences. But the Constitution means something different by “We the People.” These words don’t just refer to voters and their preferences of the moment. And they don’t mean that a populist president who claims that his personality reflects the desires of the people has a mandate to ignore the requirements of the law. Rather, “We the People” is an ideal of a “constitutional” people—citizens not only versed in the Constitution, but who demand that public officials, especially the president, comply with it.

Lincoln explained this constitutional ideal when he distinguished between people’s base instincts and their “better angels.” Later, eulogizing the war dead at Gettysburg, Lincoln explained that ours was a government “of the people, by the people, [and] for the people.” That phrase best explains the Constitution’s meaning and how it treats the ideal of a constitutional people. We are a government “of” the people, because ultimately all government officials work for and are accountable to “We the People”—an idea expressed in the Constitution’s first three words. We are a government “by” the people, in that we participate in elections and in lawmaking. Finally, we are a government “for” the people, because we recognize in our founding document that each of our fellow citizens is a rights holder. Without the right to free speech, we could not conceive of the ideas necessary to make democratic decisions. If we were denied religious freedom, we could not truly develop our own beliefs.

The Constitution protects this higher ideal of “the people” most obviously through the Bill of Rights—the first ten amendments to the Constitution. But the structure of the original Constitution itself also protects the rights of the people. Madison gave the best early explanation of the Constitution’s ideal of “the people.” To him, the Constitution protected not just against kingly domination, but also against the “tyranny of the majority.” A president might become a tyrant by catering to the worst prejudices of the populace, but Madison argued that the people could never be stripped of their rights—even if a large majority of people favored such a move. Those rights allow the people to be the Constitution’s best protector. Sometimes, the people can exact punishment on an errant president indirectly, by working through the other branches: for example, by demanding vigilance from Congress. But the people can also take action directly, using rights like the First Amendment’s free speech protection to criticize a president.

As president, you will be constrained by these legal dynamics of the Constitution. But far more integral to your presidency is something else: the Constitution’s political morality. By this, I mean the values of freedom and equality that inform the document beyond its judicially enforceable requirements. We can tell whether presidents embrace the Constitution’s values not just by their executive orders or official appointments, but by how they speak to the American people. No court can tell you what to say. But you still must be guided by the Constitution in this crucial endeavor. As president, you should speak for all of us—and more, you should speak for what our country stands for, and aspires to be. …

Some people may tell you that you have to choose between the words and the principles of the Constitution when interpreting the document, or that you should just listen to the Supreme Court. None of these approaches is complete. Looking to the Constitution’s text, the history of Supreme Court rulings, and the broader values underlying the Constitution gives us the best method to resolve constitutional disputes and discover the document’s meaning. I refer to this approach as value-based reading.

So what are constitutional values? They are best understood as principles of constitutional self-government—principles that realize the ideal of an American populace with all citizens regarded as equal, always retaining their right to rule and influence public life. Although the text of the Constitution is the first place to look for signs of these values, they have also been argued over and worked out through Supreme Court cases throughout American history. We will look to these cases as an important guide to the Constitution, sometimes invoking the conclusions of the court’s justices and, where necessary, pointing to how the case law should evolve to better reflect the Constitution’s deeper values. And throughout, we will come back to the architect of the Constitution itself: James Madison. In the Federalist Papers, his public speeches, and other writings, Madison is essentially speaking to us across the ages.

We should listen.

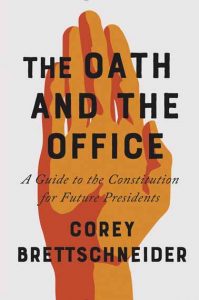

Corey Brettschneider ’95 is professor of political science at Brown University.

Excerpted from The Oath and the Office: A Guide to the Constitution for Future Presidents. Copyright © 2018 by Corey Brettschneider. Excerpted by permission of W. W. Norton & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Browning of the New South

The Browning of the New South The Sweeney Sisters

The Sweeney Sisters The Eye That Never Sleeps

The Eye That Never Sleeps Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling & Production

Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling & Production The Religion of Physics

The Religion of Physics Aphrodite’s Pen

Aphrodite’s Pen Devotional Thoughts on the Lord’s Supper, Offering and Prayer

Devotional Thoughts on the Lord’s Supper, Offering and Prayer Collisions at the Crossroads:

Collisions at the Crossroads: Luxury, Blue Lace

Luxury, Blue Lace More Than Birding:

More Than Birding: Learning to Be a Foreigner:

Learning to Be a Foreigner: Buzz Stories at Thirty Thousand Feet

Buzz Stories at Thirty Thousand Feet The Also-Rans:

The Also-Rans: The Philosophical Baroque:

The Philosophical Baroque: The Nature of Hope:

The Nature of Hope: