A Democracy Reader: Part 1: Polarization and Violence

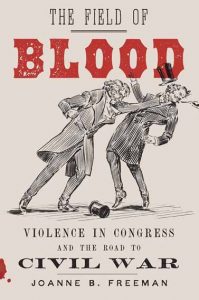

Excerpted from: The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War, by Joanne Freeman ’84 – Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018, 480 pages, $28.

Part 2: The Authoritarian Pandemic

Part 3: The Oath and the Office (Excerpt)

Part 4: The First Amendment in Action

Part 5: How Democracies Die (Excerpt)

Part 6: Policing the Police

Writing this book was an emotional process. Immersing myself in extreme congressional discord and national divisiveness at a time of extreme congressional discord and national divisiveness was no easy thing. At various points, I had to walk away and get some distance. At other points, unfolding events sent me scurrying to my keyboard to hash things out. Of course, there are worlds of difference between the pre–Civil War Congress and the Congress of today. But the similarities have much to tell us about the many ways in which the People’s Branch can help or hurt the nation.

Many years ago, when I began researching this book, it was far less timely and far more puzzling. There seemed to be so much violence in the House and Senate chambers in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s. Shoving. Punching. Pistols. Bowie knives. Congressmen brawling in bunches while colleagues stood on chairs to get a good look. At least once, a gun was fired on the House floor. Why hadn’t this story been told?

That question is answered in the pages that follow, which reveal for the first time the full scope and scale of physical violence in Congress between 1830 and the Civil War. Yet even knowing that answer, I didn’t fully grasp how such congressional fireworks could remain undercover until last year. In a long and intimate Politico interview, former House Speaker John Boehner revealed that some time ago, during a contentious debate over earmarks (items tacked onto bills to benefit a member of Congress’s home state), Alaska Republican Don Young pushed him up against a wall in the House chamber and threatened him with a knife. According to Boehner, he stared Young down, tossed off a few cusswords, and the matter ended. According to Young, they later became friends; Boehner was best man at Young’s wedding. And according to the press reports that addressed the incident, it wasn’t the first time that Young pulled a knife in the halls of Congress. In 1988, he reportedly waved one at a supporter of a bill that would have restricted logging in Alaska. (He also angrily shook an oosik—the penis bone of a walrus—at an Interior Department official who wanted to restrict walrus hunting in 1994, but that’s an entirely different matter.) Two of these confrontations made the papers when they happened, but only recently has the Boehner showdown come to light. Remarkably, even in an age of round-the-clock multimedia press coverage, what happens in Congress sometimes stays in Congress.

From a modern vantage point, it’s tempting to laugh—or gasp—at such outbursts and move on, and sometimes that’s merited. (The oosik incident is definitely worth a chuckle.) As alarming as Young’s knifeplay seems, it says less about a dangerous trend than it does about a somewhat flamboyant congressman.

And yet congressional combat has meant much more than that— especially in the fraught final years before the Civil War. In those times, as this book will show, armed groups of Northern and Southern congressmen engaged in hand-to-hand combat on the House w floor. Angry about rights violated and needs denied, and worried about the degradation of their section of the Union, they defended their interests with threats, fists, and weapons.

When that fighting became endemic and congressmen strapped on knives and guns before heading to the Capitol every morning—when they didn’t trust the institution of Congress or even their colleagues to protect their persons—it meant something. It meant extreme polarization and the breakdown of debate. It meant the scorning of parliamentary rules and political norms to the point of abandonment. It meant that structures of government and the bonds of Union were eroding in real time. In short, it meant the collapse of our national civic structure to the point of crisis. The nation didn’t slip into disunion; it fought its way into it, even in Congress.

The fighting wasn’t new in the late 1850s; it had been happening for decades. Like the Civil War, the roots of congressional combat ran deep. So did its sectional tone and tempo; Southern congressmen had long been bullying their way to power with threats, insults, and violence in the House and Senate chambers, deploying the power of public humiliation to get their way, antislavery advocates suffering worst of all. This isn’t to say that Congress was in a constant state of chaos; it was a working institution that got things done. But the fighting was common enough to seem routine, and it mattered. By affecting what Congress did, it shaped the nation.

It also shaped public opinion of Congress. Americans generally like their representatives far more than they like the institution of Congress. They like them all the more if they are aggressive, defending the rights and interests of the folks back home with gusto; there’s a reason why Don Young’s constituents have reelected him twenty-three times. The same held true in antebellum America; Americans wanted their congressmen to fight for their rights, sometimes with more than words.

This was direct representation of a powerful kind, however damaging it proved to be. The escalation of such fighting in the late 1850s was a clear indication that the American people no longer trusted the institution of Congress to address their rights and needs. The impact of this growing distrust was severe. Unable to turn to the government for resolution, Americans North and South turned on one another. The same held true for congressmen; despite the tempering influence of cross-sectional friendships, they, too, lost faith in their sectional other. In time, the growing fear and distrust tore the nation apart.

Toward the start of my research, I discovered poignant testimony to the power of congressional threats and violence. It took the form of a confidential memorandum with three signatures on the bottom: Benjamin Franklin Wade (R-OH), Zachariah Chandler (R-MI), and Simon Cameron (R-PA). And it told a striking story.

One night in 1858, Wade, Chandler, and Cameron—all antislavery—decided that they’d had enough of Southern insults and bullying. Outraged by the onslaught of abuse, they made a difficult decision. Swearing loyalty to one another, they vowed to challenge future offenders to duels and fight “to the coffin.” There seemed to be no other way to stem the flow of Southern insults than to fight back, Southern-style. This was no easy choice. They fully expected to be ostracized back home; in the North, dueling was condemned as a barbaric Southern custom. But that punishment seemed no worse than the humiliation they faced every day in Congress. So they made their plans known, and— according to their statement—they had an impact. “[W]hen it became known that some northern senators were ready to fight, for sufficient cause,” the tone of Southern insults softened, though the abuse went on. The story is dramatic, but what affected me most when I first read it was the way the three men told it; even years later, they could barely contain themselves. “Gross personal abuse” had an impact on these men, and it was mighty. Not only did it threaten “their very manhood” on a daily basis, but by silencing Northern congressmen, it deprived their constituents of their representative rights, an “unendurable outrage” that made them “frantic with rage and shame.” To Wade, Chandler, and Cameron, sustained Southern bullying wasn’t a mere matter of egos and parliamentary power plays. It struck at the heart of who they were as men and threatened the very essence of representative government.

They had to do something. And they did.

These men were doing their best to champion their cause and their constituents in trying times, and they said so in their statement. They had written it “for those who come after us to study, as an example of what it once cost to be in favor of liberty, and to express such sentiments in the highest places of official life in the United States.” They were pleading with posterity—with us—to understand how threatened they had felt, how frightened they had been, how much it had taken for them to fight back, and thus how valuable was their cause. In a handful of paragraphs, they bore witness to the presence and power of congressional violence.

When I first read their plea, it brought tears to my eyes. It was so immediate and yet so far away. It was also stunningly human, expressing anger and outrage and shame and fear and pride all in one. Not only did it bring the subject of this book to living, breathing life, but it showed how it felt to be part of it. By offering a glimpse of the emotional reality of their struggle, Wade, Chandler, and Cameron opened a window onto the lost world of congressional violence.

The lessons of their time ring true today: when trust in the People’s Branch shatters, part of the national “we” falls away. Nothing better testifies to the importance of Congress in preserving and defining the American nation than witnessing the impact of its systemic breakdown.

Joanne Freeman ’84 is the Class of 1954 Professor of American History and of American Studies at Yale University.

“Author’s Note” from THE FIELD OF BLOOD: VIOLENCE IN CONGRESS AND THE ROAD TO CIVIL WAR by Joanne B. Freeman. Copyright © 2018 by Joanne B. Freeman.

Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux.