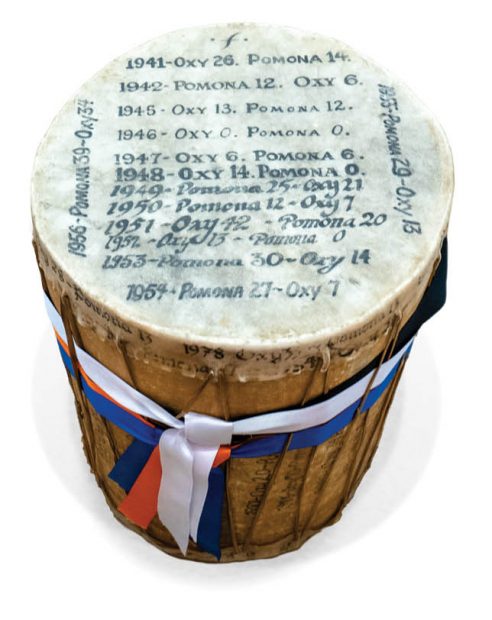

‘Artifact’ Stirs Athletics Memories

As someone who practiced the gridiron arts on Merritt Field for several years—toiling beneath the torrid San Gabriel Valley sun, stately oak tree, and watchful eye of legendary coach Roger “RC” Caron—I greatly enjoyed the “A Drum Falls Silent” piece in the Fall/Winter 2021 edition. My mother and uncle, who were taken to the bonfire rallies during the 1950s by my grandfather, former Dean of Men Shelton Beatty, confirm that they were, indeed, a “huge tradition,” if a bit haphazardly staged—one year, the inferno almost toppled onto the fieldhouse that preceded the Rains Center.

As someone who practiced the gridiron arts on Merritt Field for several years—toiling beneath the torrid San Gabriel Valley sun, stately oak tree, and watchful eye of legendary coach Roger “RC” Caron—I greatly enjoyed the “A Drum Falls Silent” piece in the Fall/Winter 2021 edition. My mother and uncle, who were taken to the bonfire rallies during the 1950s by my grandfather, former Dean of Men Shelton Beatty, confirm that they were, indeed, a “huge tradition,” if a bit haphazardly staged—one year, the inferno almost toppled onto the fieldhouse that preceded the Rains Center.

Speaking of the Rains Center, its walls and display cases are [of course] adorned with a veritable cornucopia of similarly absorbing artifacts. I recall in particular the 1984 Summer Olympics posters strategically placed around the complex, along with the panoramic photograph, across from the laundry room at the west entrance, depicting the scene at the Los Angeles Coliseum during one of those 1920s Pomona-USC football games.

I, for one, would not complain, if this “Artifact” item became a running feature, exploring a different Rains Center piece of memorabilia each issue!

—Doug Meyer ’01

Watertown, Massachusetts

Renaissance People

Reading the Fall/Winter 2021 issue of PCM, I noticed diverse, contrasting interests and pursuits of individual Sagehens.

Among the Fulbright award recipients, I was struck by physics major Adam Dvorak ’21, who planned to conduct research in Denmark studying the effects of extreme weather events. Then comes the 21st century Pomona Renaissance quality: “While in Denmark, Dvorak aims to teach violin.”

Jarrett Walker ’84 is an international expert on the vital issue of public transportation, and a “Renaissance man.” He was a math major at Pomona and has a drama, literature and humanities Ph.D. from Stanford.

I also discovered some real human gems in the obituaries. Chalmers Smith ’51 practiced law in San Jose while playing viola in the San Jose Symphony and in string quartets. Elizabeth “Betty” Kohl Hendrickson ’60, a chemist, cared full-time for her three children until they were in high school, published 20 chemistry research papers with her husband, and learned to play the hammered dulcimer at age 61. Julia “Judith” Moore ’66, Pomona magna cum laude graduate, Peace Corps volunteer, graphic designer, Stanford MBA and a vice president in marketing at Marriott, left the corporate world to focus on painting, exhibiting at galleries and a museum.

We tend to occupy ourselves with big things, big dreams, big bank accounts, great estates, statistics, information systems, huge data banks, numerous vehicles, mass production, globalization. If we can locate what is small and of genuine interest and high quality and not just what is great or popular and famous, we can give the small the attention it is due such that it flourishes, and everyone benefits.

—Alan Lindgren ’86

North Hollywood, California

Farewell to a PCM Storyteller

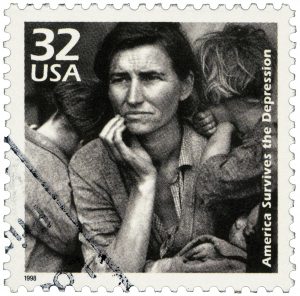

Photo by RICK LOOMIS/Los Angeles Times

Agustin Gurza, whose writing appeared in PCM for more than a dozen years, died unexpectedly in January at 73. A former Los Angeles Times columnist and critic, Gurza wrote in the Times that “I can’t go anywhere without gathering stories, like lint on a coat. Stories about people helping out, moving up, fighting back.” His first piece for PCM, “El Espectador” in 2009, was about Ignacio Lutero Lopez ’31, groundbreaking founder of a Spanish-language newspaper covering Pomona Valley barrio communities. Gurza’s final PCM story, “American Crossroads,” about UCLA Professor Genevieve Carpio ’05, appeared in our last issue. PCM’s editors appreciated Gurza’s writing talents, his deep commitment to telling the stories of his subjects and his friendship from afar. We send condolences to his loved ones, including two siblings who are alumni, Piti Gurza Witherow ’73 and Roberto Gurza ’80.

1943 Alumnus Cherishes Calendars

Today I received my new calendar,

The Pomona College Engagement Calendar.

I graduated in the Class of ’43.

Pomona has sent me seventy or more.

I am guessing there were no calendars

In the war years, ’44 and ’45.

I think the development function

Was resumed in ’46.

As a fund-raising technique

It has really worked with me.

I never forget my alma mater

When I write my dates on the calendar.

I do a month-at-a-time

On one perfect page.

I can see where I am going

And know where I have been.

I have never lived in Southern

California since my college days,

But I love the recollections

Of life around the Quad.

I worked nights and weekends

In Harwood for the girls.

I ate my meals in Frary

Along with all the other boys.

Chemistry was learned with Tyson

And calculus with Jaeger.

Basic botany with Munz

Was an outstanding privilege.

It’s hard to remember all

The names, but I’ll never forget,

“Let only the eager, thoughtful

And reverent enter here.”

It’s the calendars that have

Provided the yearly stimulation

To give back and to feel

And express gratitude.

—Lewis Perry ’43

Oakland, California

Editor’s note: The Pomona College Engagement Calendar is sent out in late summer to members of our Sagehen community. Alumni, families and friends of Pomona who have given to the Annual Fund in the previous year automatically receive the calendar. The first year the calendar was published is unknown.

As we go to press, students are once again attending classes in Crookshank and Carnegie, Pearsons and Pendleton, the many Seaver buildings and all the other places you remember.

As we go to press, students are once again attending classes in Crookshank and Carnegie, Pearsons and Pendleton, the many Seaver buildings and all the other places you remember.

This isn’t over, not by a long shot. America’s cities are still in turmoil, as are hearts and minds across the world, after we watched the horrifying death by suffocation of George Floyd, an African American man whose life was snuffed out under the knee of a police officer over 526 seconds. He pleaded for his life, asked for his mother. Onlookers begged the officers holding Floyd’s neck and body to the ground to stop—to have mercy.

This isn’t over, not by a long shot. America’s cities are still in turmoil, as are hearts and minds across the world, after we watched the horrifying death by suffocation of George Floyd, an African American man whose life was snuffed out under the knee of a police officer over 526 seconds. He pleaded for his life, asked for his mother. Onlookers begged the officers holding Floyd’s neck and body to the ground to stop—to have mercy. IT’S HARD TO THINK of two greater opposites than a school and a prison.

IT’S HARD TO THINK of two greater opposites than a school and a prison.