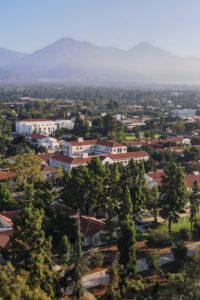

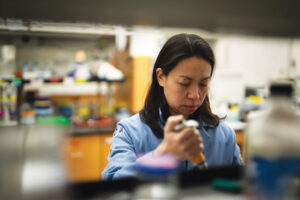

Geology Professor Nikki Moore took a team to the “exposed granites” of the White Mountains, nestled in the Sierras.

The sun is setting over the White Mountains an hour west of Nevada as Visiting Assistant Professor of Geology Nikki Moore and Ruth Vesta-June Gale ’25 set up portable chairs some 8,000 feet above sea level.

Grandview Campground—where the two are staying this August weekend—is a certified dark sky location, a haven for stargazers and astronomy groups. From here, once darkness consumes the light, the Milky Way and other collections of stars dot the sky.

As Moore, Pomona visiting assistant professor of geology, and Gale relax after a day of collecting rock samples from ancient dikes, meteors sparkle overhead before darting south and vanishing into the horizon.

While most appear and disappear within seconds, one stays visible long enough for Moore to audibly gasp.

The brightest and longest shooting star she’s ever seen.

“There’s a connection I have with nature where I can have these special moments that stick with me for a lifetime,” she says.

For Gale, a geology and applied math double major, the three-day trip to the Lone Pine area marked her second year doing fieldwork with Moore. She says the chance to visit the White Mountains—one of the lesser-explored ranges in the Sierra Nevada region—for the first time this summer was too good to pass up.

“You think of mountains and [that] they’re big, but it’s something else when you’re hiking on them,” Gale says. “We had some remote dikes we were trying to access, and they weren’t the worst hikes, but you’re off the trail so you don’t realize the magnitude of the mountains until you’re on them. It was satisfying to conquer them, to do science in this massive area.”

Lynn Robinson, Nikki Moore and Ruth Vesta-June Gale ’25 at the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest in the White Mountains to see Methuselah, confirmed to be the oldest tree in the world (4,856 years and counting…)

Studying Dikes

Moore’s expertise combines her three passions: geology, teaching and nature. From collecting rocks as a child growing up in Nebraska to visiting the Rocky Mountains with friends as a teenager, Moore became equal parts fascinated with how immense mountains are and determined to understand how they came to be.

While an undergrad at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, Moore found herself a tutor for friends and peers. “I found that I had an innate sense of joy in sparking an interest for someone else and breaking down something complex to someone else and seeing their eyes light up with understanding and excitement,” she says.

Thanks to a roughly $200,000 National Science Foundation EMpowering BRoader Academic Capacity and Education (EMBRACE) grant, Moore traveled to the eastern Sierra, the White Mountains and the Benton Range this summer to explore dike swarms—the plumbing of magmatic systems found on Earth and other planetary bodies.

Moore’s field, geochemical and geochronological work on the dikes, blends teaching and research. It is a perfect fit for a grant program intended to give undergraduate faculty the time and means to step away from or reduce their teaching load to develop a robust research program.

Dike swarms “are the feeders for volcanic eruptions in a range of geologic settings,” she says, “and thus are the connection between magmas that are generated deep in Earth’s mantle and those that travel through the crust to be erupted at the surface.”

Because swarms exist from the deep geologic past, Moore says, they “can provide important evidence to help reconstruct the magmatic history of these regions.”

According to Moore, understanding the whole volcanic process—from how magmas first form in the “mantle,” then move through the crust and erupt at the surface—is imperative to learning how and why volcanic eruptions happen in different parts of the world.

A rock that’s part of the massive Independence Dike Swarm, which extends more than 370 miles across California.

This summer, she planned three trips to the Sierra Nevada, each accompanied by different Claremont Colleges students. Together, professor and student hiked to dikes Moore targeted and mapped, collecting a compositional range of dike rock samples for lab analysis.

“What I really enjoyed about this experience is how much I could ask Nikki about what’s going on in the field,” Gale says. “I could toss around ideas with her and make sure I understood what’s going on and what the research is trying to prove.”

Studying the chemical composition of the samples they collected this summer will help the team confirm whether the Independence Dike Swarm is 148 million years old, as experts believe, or if the dikes started to emerge even earlier, as preliminary data suggests.

“My study is unique in that the dikes were the conduits through which volcanic eruptions were produced at the surface, during the time the whole Sierra Nevada arc was forming,” Moore says. “Those volcanoes that once existed are now eroded away, and the core of the Sierras are now the exposed granites.”

Sagehens in the Sierra

Pomona College geologists have long used the Sierra Nevada as a proving ground for many core concepts on how magmas form, crystallize and build the crust, says Jade Star Lackey, professor of geology and an authority on the region.

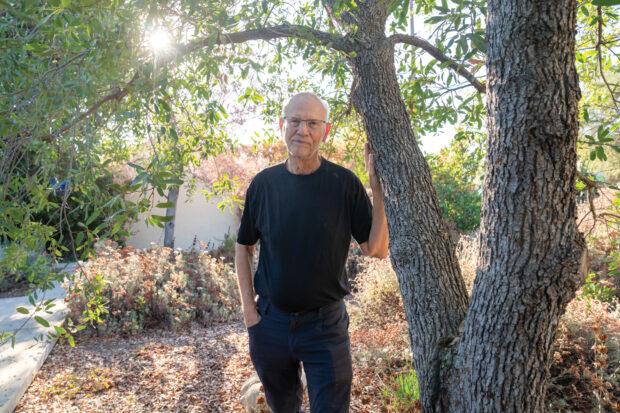

Jade Star Lackey and Nikki Moore

Magmas produce igneous rocks, which can cool and solidify in one of two places: within the crust or erupted at the surface. The magmas that stall, cool and entirely solidify in the crust are plutonic rocks, such as granite.

Spanning some 24,000 square miles, the Sierra has 50 million years’ worth of different granites from all compositions, making it a mecca for geologists and geology students. A room on the first floor of Edmunds Hall is filled with salt-and-pepper granite collected from the Sierra Nevada over the years, each its own piece of Earth history.

“The rocks speak for themselves,” Lackey says, “but then there’s a Sagehen connection in terms of the scholarly research that’s happened on them.”

Sierra Nevada Stats

- 3 national parks

- 25% of California’s land area

- 60% of California’s annual precipitation

Art Sylvester ’59, who taught geology for more than 35 years at the University of California, Santa Barbara, cut his teeth navigating the region’s ridges, canyons and terrain as an undergraduate at Pomona. Sylvester, who died in 2023 at age 85, later co-authored Roadside Geology of Southern California, a popular addition to the Roadside Geology series of books published by Mountain Press.

Allen Glazner ’76, professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, also traversed the Sierra as a student and later, a professional, writing a series of books that includes volumes on Death Valley and Yosemite.

Glazner and Sylvester collaborated on the 1993 tome Geology Underfoot in Southern California.

“All the work they’ve done started by realizing just how much science could be done in the Sierras because of the sheer scale of it,” Lackey says. “It’s also important as an analog for a lot of other great granite terrains that form the Ring of Fire in Japan, Russia and Canada.”

Q&A with Professor of Geology Jade Star Lackey

Lackey first navigated the Sierra Nevada as a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Decades and countless trips to the iconic mountain range later, Pomona’s chair of geology remains fascinated by the vast expanse of granite.

Q: What drew you to geology?

A: I’d always been around parents who liked to be outside. Because they lived in rural areas, they eschewed the urban existence. My father was a commercial fisherman so he lived on the coast, and we had enough areas of land where I could go explore. From an early stage I was watching the river and noticing the river change colors during the year. I always tell my students about my own introductory geology class, where a lot of it was intuitive because I’d had enough experiences. It was learning that there was so much more to learn; to teach my mind to see what’s in the rocks. Suddenly I became a storyteller where I can look at the layers in a rock and see an interruption in the layers as being a profound event. Fast forward to where I am now, and it’s about trying to help people spark their imagination—to be able to say, ‘That’s not just a static rock, that’s a story.’ Marcia Bjornerud, a professor at Lawrence University, says that rocks aren’t nouns, they’re verbs.

Q: Describe the student-faculty dynamic within Pomona’s Geology Department.

A: We have a lot of resources that other geology departments don’t have, so we can get students doing high-level research immediately. The department’s good at supporting the student who’s curious. If they can get their schedule clear, then they’re unlimited in what they can do. Some people are really good at spotting certain subtleties in an outcrop, whereas the big picture thinker might recognize how to hike around a field site looking for the contact between two granite bodies. You work with students in that regard to get a sense of how they think. It’s never about who can swing a rock hammer the hardest. There’s been a misconception of geology in the past where it was only bearded guys and solitude. We like to dispel that here. We’re a cooperative. If it’s making meals in camp or collecting and carrying samples back, all of that is part of the experience.

Q: Having been to the Sierra Nevada so often, what keeps fieldwork there fresh?

A: There’s this micro-Sierra that you’re always studying when you’re trying to understand the differences in the rocks, and then there’s the macro—the vistas, the Ansel Adams Sierra Nevada that people talk about. That part never gets old. I’m always on the move as a geologist. I’m not coming back to the same lake every year to fish. I’m off the main trail, so there are many places we go where people haven’t been in decades. We’ll find archaeological things and markers that were put there by shepherds or people before them. Those are the things that keep it fresh for me—just always asking new questions around the next mountain or ridge.

interview conducted by Brian Whitehead

Budding Geologists

At Pomona, Lackey and Moore are part of a Geology Department that draws students from across The Claremont Colleges fascinated by nature and the chance to study science outside the traditional biology and chemistry disciplines.

Little time is wasted getting these inquisitive minds into the field.

There is no substitute for hands-on experience, Lackey says, be it outside or in the lab. As thrilling as collecting dike and granite samples from the Sierra can be for one student, equal thrill can be found by another student in preparing a sample to examine under the microscope for years to come.

“There’s enough breadth of science in geology that it’s really appealing to students,” Lackey says. “It gives you the opportunity to practice all over the world if you want to. So often we go out there looking to answer science questions, but there’s so much we can do in the Sierra that brings the classroom alive.”

He says that students with the time to accompany faculty on multi-day trips are in high demand, and the breathtaking views of the Sierra are a good incentive. Between Yosemite, Sequoia and Kings Canyon, the scenery is second to none.

“There’s a lot of power in the landscape,” Lackey adds. “The rock falls we see, or the damage that an avalanche has done to trees that are snapped off, and the really big snow years we had a couple years ago—that’s the kind of stuff that’s stunning, and is why this is such a good place for both teaching and research.”

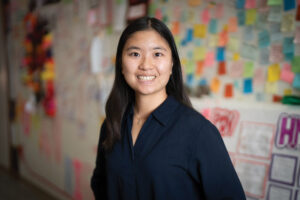

Khadi Diallo ’25 joined Moore for a July trek to Onion Valley. Their days began at 8 a.m. and ended by 3 p.m. due to the extreme heat occurring in the lower elevations of the Owens Valley region. In those seven hours, the two navigated as much of the mountain area as they could in search of rock samples.

“I was in constant awe of the mountains,” Diallo says. “There’s something particular about mountains, too, where you’re looking at them from a distance and feel both very big and very small. You come up to the mountains and realize the sheer magnitude of geology there.”

For Diallo, a geology major and California native, the six-day experience was as fulfilling as she expected. Joining Moore in the field helped Diallo connect the idea of geology mapping with how it’s used in the real world. Some geologists spend their entire careers mapping the Sierra, paving the way for easy sampling.

“It’s a lot of work built on that of other geologists,” Lackey says. “And that’s what makes the Sierra so good. It’s really well mapped. The quadrangles across the Sierra. I used those, and it was the names on those maps that I would then connect back to Pomona people.”

Moore, who used these extensive, pre-existing maps to plan and execute her fieldwork, likes to say she “stands on the shoulders of giants who did so much incredible work before us.”

A Quick Geology Glossary

Crust

the outermost layer of Earth, composed largely of silica and oxygen, making it light-/low-density compared to other more internal layers. It comprises the rocky surface upon which all life dwells.

Mantle

the middle and most voluminous layer of Earth, composed largely of silica, iron, magnesium and oxygen, in which most of Earth’s magmas are generated.

Magma

molten/liquid rock that cools to form igneous rocks, either within Earth as plutonic rocks, or erupted at the surface of Earth from volcanoes. Magmas can also contain mineral crystals that have cooled and solidified, gases such as water and carbon dioxide, and xenoliths, which are pieces of pre-existing rock that are accidentally incorporated into the melt.

Dike

a vertical intrusion of magma, that allows magma to move from deep in the mantle or crust to the surface. These pathways are created by pre-existing fractures in rocks. A dike swarm is a group of dikes that cover a wide area and often are similarly oriented or arranged in a particular geometry.

Fused rock powder

a rock that has been broken into small pieces, then ground into a powder, and then melted at 1000 °C (~1800 °F) to produce a glass bead for chemical analysis.

Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS)

an analytical technique used to determine the abundance of particular elements in rocks, especially those that are in very small abundance (called “trace elements”); this technique is also used to measure the ratios of isotopes, which can be essentially used as clocks that record the formation age of rocks or their constituent minerals.

One With Nature

Moore savors the remoteness of being in the field.

While extroverted by nature, she finds truly special leaving the beaten path for secluded spaces where mountain ranges dwarf everything in sight.

“Very often I get this feeling of standing on a spot and possibly being one of the few human beings to ever stand there or trod across that particular region,” Moore says. “That’s what gives me this deeper connection with the places I go. It just makes the work more intimate.”

Very often I get this feeling of…being one of the few human beings to ever trod across that particular region. It just makes the work more intimate.”

—Visiting Assistant Professor of Geology Nikki Moore

Lackey, too, appreciates the novel terrain, smells and sights of the Sierra—though the bears have gotten boring, he must admit.

“When you hear a rockslide in the silence of the mountains it is simultaneously terrifying, but also profound,” he says. “We find human artifacts that are really old, way markers in places where nobody else travels.”

After relaxing and volunteering for much of the summer, Diallo says traveling with Moore to the Sierra Nevada “got my mind churning back to geology.”

Khadi Diallo ’25 near a dike sampling site at Onion Valley.

Diallo even plans to incorporate her summer research into her senior thesis.

“As a geology student it’s good to get fieldwork into your repertoire,” she says. “It’s important to get a taste of it to see if it’s something you like—and I do!”

She’s not alone.

“I had a great time—mostly because of the unexploredness of it all,” Gale says. “The trip was a real-world application of all the tools I’ve studied so far in college.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story described the Sierra as spanning “some 24,000 square feet,” instead of 24,000 square miles. The mountain range is much more than half an acre! (Spinal Tap Stonehenge, anyone? Thanks for the tip, Peter Wechsler ’68).

Kendrick Lamar

Kendrick Lamar Childish Gambino

Childish Gambino H.E.R.

H.E.R. Doja Cat

Doja Cat Khalid

Khalid