As a thought experiment, we asked alumni, faculty and staff experts in a wide range of fields to go out on a limb and make some bold predictions about the years to come. Here’s what we learned…

As a thought experiment, we asked alumni, faculty and staff experts in a wide range of fields to go out on a limb and make some bold predictions about the years to come. Here’s what we learned…

Start reading (What’s Next in Revolutions?)

As a thought experiment, we asked alumni, faculty and staff experts in a wide range of fields to go out on a limb and make some bold predictions about the years to come. Here’s what we learned…

As a thought experiment, we asked alumni, faculty and staff experts in a wide range of fields to go out on a limb and make some bold predictions about the years to come. Here’s what we learned…

Start reading (What’s Next in Revolutions?)

Dorsey on a street in Greensboro (All photos by Porfirio Solórzano)

SOMETHING’S HAPPENING in Greensboro, Alabama.

The crisp winter air buzzes with activity one morning in early January: from construction at the historic Seay house to a pompom-making session at a nearby Victorian farmhouse to jokes and laughter in the converted kitchen of an old hotel downtown.

If you’re looking for a kudzu-wrapped cliché about well-meaning do-gooders who rescue a fading town and its impoverished citizens—well, this isn’t that.

“People have told the same old story over and over about Greensboro,” Dr. John Dorsey ’95 says. “This is a new story of potential and hope and movement forward.”

It’s the collision of past and present and future, all having a meeting in the middle of Main Street. In historic buildings downtown, brick residences serving as temporary office space and housing and a restored Victorian several miles away, Dorsey is leading a charge to provide a range of services through a series of community-based programs he founded under the name of Project Horseshoe Farm. These include adult and youth programs addressing mental and physical health, housing and after-school care, plus gap-year fellowships and internships for top recent college graduates from around the country.

His methods are creating a new model for the way mental health care and community health are addressed in communities while simultaneously helping reshape a thriving downtown and preparing the next generation of social entrepreneurs to create their own paths.

Dorsey, a licensed psychiatrist, initially thought he’d live closer to his family in California.

Dorsey conducts a meeting with the Project Horseshoe Farm fellows in a room that is undergoing renovation by students of the Auburn University Rural Studio architecture program.

However, part of him was pulling him to a more personal way of living and practicing medicine. A tip from a colleague at a medical conference led him to an interview at Bryce Hospital in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. While driving cross-country to begin working, however, he learned Bryce no longer needed his services. Unsure of what he would find in Alabama, he drove on to Tuscaloosa and took cover in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in a motel room.

His savings dwindling, he had to come up with a plan—and a place to live—fast.

“I stumbled upon a mobile home sales office in Moundville and asked them to rent me a mobile home. They sent me down to Greensboro and connected me with a local pastor and nonprofit director,” Dorsey remembers.

“It was a quintessential small town with interesting energy, and they didn’t have a psychiatrist,” he says. “That’s how I ended up here 12 years ago. There was no plan that I was going to Greensboro.”

And yet, this little town of 2,365 residents would turn out to be exactly the kind of community where Dorsey could carry out his grassroots vision of integrated, community-based health care—a vision that he developed in medical school while studying what he terms a “frustrating” disconnect between doctors and patients.

“‘Focusing my residency on community psychiatry and people on the margins really crystallized the mismatch: You have to understand the person’s housing, transportation, finances and relationships,” Dorsey says. “There’s a spectrum, and when you have someone who is homeless, in chaotic relationships or who abuses drugs or alcohol, a test in an ER or primary care setting won’t solve their issues. I wanted to set up systems to address the needs of the patients, particularly in underserved communities.”

Dorsey visits with children at Greensboro Elementary School during an after-school program.

Since then, Project Horseshoe Farm has grown through a series of small steps, beginning with an after-school program for kids that met a community need. Then, in 2009, Dorsey began building a housing program for women with mental illness. He also selected his first group of three student fellows to spend a year partnering with the community and learning to take care of patients in a holistic way. He describes his success at attracting them to a brand-new nonprofit with no reputation in little Greensboro, Alabama, as “a miracle. We had great fellows right from the start and have grown ever since.”

As the project celebrated its 10th anniversary last year, it had expanded to encompass a range of other services as well, including the Adult Day program, a kind of community center where people come together for companionship and mutual support, and the Health Partners program, pairing individual fellows with vulnerable adults to help them navigate the complexities of health care and social services.

Seeing is believing, so Dorsey offers a tour of downtown and Project Horseshoe Farm, starting at the old Greensboro Hotel property, donated to Project Horseshoe Farm in 2014 for use as a community center and project headquarters. Located right on Main Street, the old hotel was once listed as a historic building in peril, but now it’s being lovingly restored. One can see glimpses of its former grandeur in the embossed ceilings, pale mint walls and gleaming wood floors. w

Project Horseshoe Farm fellow Greta Hartmann (second from left) plays dominos with adults in the community center on Greensboro’s Main Avenue

“There is such a rich, complex history here,” Dorsey says. His tone is reverent. In addition to being a hotel, the building also once housed a dress shop, a café and a sewing plant that employed some who now come through its doors as patients.

This morning, the place is bustling with students preparing a meal and guests in conversation. Kevin Wang, a first-year fellow from Northwestern University and future medical student interested in health care delivery systems, steps away from lunch preparations to describe his own experience here. “I was surprised at how willing people were to work with us, especially having no personal ties to Alabama. It’s a testament to the organization,” he says. “People know we’re here for them and understand we’re here to learn from them, and they’re willing to share. That’s really cool.”

Toward the rear of the building, retired nurse Jane Prewitt, known as “Nurse Jane,” organizes patient prescription trays with the assistance of Berkeley graduate Michelle McKinlay. “Until you truly get down here and walk with the people, you have no idea,” McKinlay says. “Walking through health care barriers with them and really getting to know people has changed me and helped me understand the issues better.”

Prewitt invites patients and visitors to sit in one of the outsized white Adirondack-style chairs that dominate the space, a striking change from the usual exam chairs or tables one might see in a doctor’s office. Her husband made them. Prewitt had brought one in to use and it was a hit with patients who found the chairs comfortable and easy to get in and out of. Another plus—staff found them easy to clean.

It’s one way the group has learned to meet needs with practical solutions. “You don’t have to be fresh out of college to understand,” Prewitt says. “You just wonder at how well people do with the minimal resources they have.”

The tour proceeds across rough-hewn floorboards and around paint cans and stacked chairs. Dorsey bounds up a flight of stairs obscured by a tarp and stands in the center of his future office. “I love the light,” he says, walking to a window to point out the corner of the room where sunlight streams in.

Administrative space is planned for the area next to his, and the closed-off third floor may one day serve as housing for students in the health professions.

“Having a community center in the heart of Main Street where people are welcome and supported is a wonderful testament to Greensboro. It’s one of Greensboro’s strengths,” Dorsey says. “In most communities, Main Street renovation is about stores and restaurants. But Greensboro has embraced having people who are usually on the margins come right downtown. It’s not just about commerce. It’s about the soul of the community.”

Being situated on Main Street also allows the students to get a sense of how the community’s pieces fit together. A few doors down, a new sandwich shop and gym have opened. Across the street is the old opera house reimagined as event rental space, plus a specialty pie shop. The Hale County library and mayor’s office are within walking distance, and a technology center offers residents Internet access.

Fellow Kevin Wang, right, offers support to resident Sylvia Deason at the farmhouse.

“There’s an interesting momentum on Main Street,” Dorsey says. “Each thing creates more movement.”

Construction equipment and stacked wood slats, piles of pale sawdust and brand new buckets of Ultra Spec 500 paint sit amid aged flooring and exposed beams. But one can see the dream taking shape throughout.

In another room upstairs, 10 church pews line one wall and windows look down over the grounds where a courtyard is being planned with the help of the Auburn University Rural Studio architecture program. “We imagine having community performances there,” Dorsey says, pointing.

Downstairs, he foresees a space where patients can gather while waiting to be seen. And he’d like to turn the grand old ballroom at the rear of the building into a fitness center for program participants. Its filigreed mantels, honeycomb-patterned floors and ornate ceiling hint at the elegant atmosphere guests once enjoyed. In many ways, that legacy of graceful hospitality and comfort is being continued.

Dorsey is quick to acknowledge that his efforts are part of a network of engaged leaders working together. He also considers the relationships he made at Pomona College instrumental. “Professor Richard Lewis worked with a group of us to start a neuroscience major and created a wonderful community. I wouldn’t have gotten into medical school without that support.”

His continued Pomona connections have also been important, Dorsey says. Tom Dwyer ’95, a founding and current Horseshoe Farm board member, was Dorsey’s first-year roommate in Harwood. “We’ve had several past Horseshoe Farm fellows who were also neuroscience majors at Pomona and who had some of the same classes and professors I had.”

For the future, he anticipates exploring opportunities to replicate Project Horseshoe Farm’s successes in other small towns, but he urges humility for anyone looking to improve a community. “The idea alone is not enough. The missing piece is understanding who people are and what they want and developing trust in order for it to work. So often people look at the deficits. But you can’t build around deficits. You build around what is beautiful and strong in an existing community.”

Dorsey’s love for Greensboro and its people is evident as he speaks. “Here you have all this richness and the complexity of the culture. It’s humanity—in one word,” he says.

He gestures to the inviting shops and businesses lining Main Street, “Ten years ago, 80 percent of this was boarded up. Now 80 percent of it is being used. People are sensing that ‘Hey, something is going on!’ You may ask, ‘How in the world is that happening in Greensboro?’

But it is.”

(Photos by Mark Wood)

THE EASIEST WAY for non-Texans to get to Marfa, Texas, is to fly into El Paso. From there, it’s a three-hour drive, the kind that turns shoulder muscles to stone from the sheer effort of holding the steering wheel on a straight and steady course for so many miles at a stretch. And when you finally get there, it looks pretty much like any dusty, dying West Texas railroad town. Except for the fact that Marfa isn’t dying at all—in fact, it’s thriving.

You may have heard of Marfa. In the past few decades, it’s gained a kind of quirky fame among art lovers. As a writer with an interest in the arts, Rachel Monroe ’06 was familiar with the name back in 2012 when she set out from Baltimore on a cross-country trek in search of whatever came next. At the time, she assumed the little town was probably located just outside of Austin, but as she discovered, it’s actually more than 400 miles farther west, way out in the middle of the high desert.

After a long day’s drive, Monroe spent fewer than 24 hours in Marfa before moving on, but that brief rest-stop on her way to the Pacific would change her life.

* * *

A NATIVE OF Virginia, Monroe is no stranger to the South, but she never truly identified as a Southerner until she came to Pomona. “I grew up in Richmond, which was, and still is, very interested in its Confederate past,” she recalls. A child of liberal, transplanted Yankees in what was then a deeply red state, she remembers feeling “like a total misfit and weirdo.”

When she got to Pomona, however, she was struck by the fact that most of her fellow first-years had never had the experience of being surrounded by people with very different opinions about culture and politics. “It wasn’t so much that I missed it,” she says, “but I saw that there was an advantage, and that it had maybe, in some ways, made me more sure of myself in what I did believe.”

It was also at Pomona that Monroe started to get serious about writing. Looking back, she credits the late Disney Professor of Creative Writing, David Foster Wallace, with helping her to grow from a lazy writer into a hardworking one. “He would mark up stories in multiple different colors of pen, you know, read it three or four times, and type up these letters to us,” she explains. “You really just felt like you were giving him short shrift and yourself short shrift if you turned in something that was kind of half-assed.”

It was also at Pomona that Monroe started to get serious about writing. Looking back, she credits the late Disney Professor of Creative Writing, David Foster Wallace, with helping her to grow from a lazy writer into a hardworking one. “He would mark up stories in multiple different colors of pen, you know, read it three or four times, and type up these letters to us,” she explains. “You really just felt like you were giving him short shrift and yourself short shrift if you turned in something that was kind of half-assed.”

She didn’t decide to make a career out of writing until the year after she graduated. In fact, she remembers the exact moment it happened—while hiking with some friends in Morocco, where she was studying on a Fulbright award. “I remember having this really clear moment when I was like, ‘I think I want to try to be a writer.’ It was one of those thoughts that arrive in your head like they came from outside of you—in a complete sentence, too, which is weird.”

A year later, she was at work on her MFA in fiction at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, but she wasn’t particularly happy. Her goal was to write short stories, but even as she was churning out stories and entering contests and submitting to journals, she felt like a fraud. “I would get these subscriptions to these magazines that I was trying to get into that were rejecting me, and I didn’t even want to read them. And at a certain point, I was like, ‘There’s something wrong here.’”

So she began to write essays, and something clicked. Essay writing immediately struck her as a more appropriate form for exploring the ideas that excited her, and after years of rejected short stories, as an essayist she found quick success.

Her first published essay, which appeared on a website called The Awl, was about a group of girls with online crushes on the Columbine killers. “I sort of related to these girls in the ferocity of their crushes,” she recalls. “Female rage is something that’s not really permitted, and so instead of being like, ‘Oh my god, I’m bullied, I’m miserable, I’m so unhappy,’ instead of owning that feeling, which is not socially permissible, then you idolize this boy who acted on it.”

Being published was good. Caring about what she wrote was great. Doing research was fun. And she no longer felt like she was faking it. Suddenly, she was off and running on a new, entirely unexpected career in nonfiction.

After completing her MFA, she stayed on in Baltimore for a couple of years, writing for a website run by fellow Sagehen Susan Dunn ’84, called Baltimore Fishbowl. And then, she simply knew it was time to move on.

“I’ve made most of my decisions in life kind of intuitively,” she explains, “so they’re hard to explain after the fact. But I had a sense that, ‘OK, I’ve plateaued here. I’ve reached some sort of limit. Time to go.’”

So she packed up her car and drove west.

* * *

ACCORDING TO THE Texas State Historical Association, the town of Marfa was founded in 1883 as a water stop and freight depot for the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway. The rail line slices straight through the heart of town, and a couple of times a day, seemingly endless freight trains come barreling through. The landscape here is flat and barren, covered with sparse grasses and low vegetation like creosote and yuccas, so you can literally see the train coming for miles. But the trains don’t stop here anymore, and their only apparent contribution to the local economy is a negative one—the cost of earplugs provided to guests in a nearby hotel.

Back in the 1940s, the town’s population topped out at about 5,000, bolstered by a prisoner-of-war camp and a military base. When those vanished after war’s end, Marfa seemed destined to slowly fade away, like so much of small-town America. But in recent years, the town’s population has stabilized at around 2,000, thanks to the two rather discordant pillars of its modern economy—arts tourism and the Border Patrol.

* * *

MONROE DOESN’T REMEMBER much about her first impression of Marfa, but she remembers the high desert landscape surrounding it. Somewhere around the town of Alpine, the scene began to shift. “All of a sudden, it just looked kind of rugged and open and empty,” she says, “and I got really excited about the way it looked. I was like, ‘Oh, I’m in the West.’”

In Marfa, exhausted from her eight-hour drive from Austin, she crashed at El Cosmico, a quirky hotel-slash-campground where visitors sleep in trailers, teepees and tents. The next day she took a tour with the Chinati Foundation, one of two nonprofits—the other being the Judd Foundation—that promote the arts in and around Marfa.

Then she drove on. But she couldn’t quite leave Marfa behind.

“When I got to L.A., I was like, ‘You know, if I moved here, I would have to get a job because it’s just expensive. And I don’t want a real job.’ Then I had this plan to drive back through Montana and Wyoming, but for some reason I kept thinking, ‘That Marfa place was real interesting.’”

Since she hadn’t been able to write much on the road (“It’s hard when you’re sleeping on friends’ couches”), she decided to return to Marfa and find a place to settle in for a week or so and write.

What drew her back to Marfa? It’s another of those intuitive decisions that she has trouble explaining. “I’m not sure I could have said at the time. I can make something up now, but I was just like, ‘Oh, that’s a cool place. It’s real pretty. It seems easy to find your way.’ It just seemed like the kind of place where you could go and be for a week and get some writing done.”

That week stretched into six. “And at the end of that, I was like, ‘I think I’m just going to move here.”

* * *

THE BORDER PATROL has been an integral part of life in Marfa since 1924, when it was created by an act of Congress—not to control immigration, but to deter the smuggling of liquor across the Rio Grande during Prohibition. That mission soon changed, however, and today, the Patrol’s Big Bend Sector—known until 2011 as the Marfa Sector—is responsible for immigration enforcement for 77 counties in Texas and 18 in Oklahoma.

Headquarters for the whole sector is just south of town, near El Cosmico, and uniformed Border Patrol agents are a conspicuous presence in Marfa’s coffee shops and on its streets. According to the sector’s website, it now employs about 700 agents and 50 support staff. Among them, Monroe says, are quite a few young men and women who grew up right here in town.

Headquarters for the whole sector is just south of town, near El Cosmico, and uniformed Border Patrol agents are a conspicuous presence in Marfa’s coffee shops and on its streets. According to the sector’s website, it now employs about 700 agents and 50 support staff. Among them, Monroe says, are quite a few young men and women who grew up right here in town.

The other pillar of Marfa’s economy doesn’t jump out at you until you walk up Highland Street toward the big pink palace that houses the Presidio County Courthouse. Glance inside the aging storefronts, and where you might expect to find a Western Auto or a feed store, you’ll find, instead, art gallery after art gallery.

The story of Marfa as a destination for art lovers begins in the early 1970s with the arrival of minimalist artist Donald Judd. Drawn to Marfa by its arid landscapes, he soon began buying up land, first the 60,000-acre Ayala de Chinati Ranch, then an entire abandoned military base. In what must have seemed a grandly quixotic gesture at the time, he opened Marfa’s first art gallery.

Then something strange and wonderful happened. Artists began to gravitate to this dry little West Texas town to be part of a growing arts scene, and behind them, in seasonal droves, came the arts tourists.

* * *

MONROE’S WRITING CAREER really took off after she moved to Marfa—a fact that she believes is no coincidence. “It wasn’t my intention in moving out here, but I think living here has been an advantage in that I come across a lot of stories,” she says. “Things kind of bubble up here—not just regional stories either.”

Some of those stories, which increasingly have appeared in prominent national venues like The New Yorker, New York Magazine, Slate, The New Republic, and The Guardian, have grown directly out of her engagement in the Marfa community. In fact, the article that really put her on the map for national editors happened, in large part, because of her decision to join the local fire department.

“I read Norman Maclean’s book Young Men and Fire,” she says. “I just loved that book, and then I was like, ‘Oh wait, I’m moving to a place where they have wildfires.’” Fighting fires, she thought, would be a good way to connect with the land, and as a writer, she was drawn by the sheer drama of firefighting. “And then, you learn so much about the town,” she adds. “You know—not just the tourist surface, but the rural realities of living in a place.”

A year later, when a fertilizer plant exploded in West, Texas (“That’s West—comma—Texas, which is actually hours east of here”), Monroe found that her status as a first responder was her “in” for an important story. In the course of the investigation, a firefighter named Bryce Reed had gone from local hero to jailed suspect. Monroe wanted to tell his story, and her credentials as a fellow firefighter were key to earning his trust.

The resulting article, which she considers her first real work of in-depth reporting, became a study of Reed’s firefighter psyche and the role it played in his ordeal and his eventual vindication. “In my experience, it’s not universal, but a lot of people who are willing to run toward the disaster, there’s some ego there,” she says. “And it seemed to me that in some ways he was being punished for letting that ego show.”

The 8,000-word piece, which appeared in Oxford American in 2014, helped shift her career into high gear. Despite her usual writer’s insecurities about making such a claim herself (“As soon as you say that, a thunderbolt comes and zaps you”), she hasn’t looked back.

Recently, she put her freelance career on hold in order to finish a book, the subject of which harkens back to her very first published essay—women and crime. “It centers on the stories of four different women over the course of 100 years, each of whom became obsessed with a true crime story,” she says. “And each of those four women imagined themselves into a different role in the story. One becomes the detective, one imagines herself in the role of the victim, one is the lawyer, and one is the killer.”

She already has a publisher, along with a deadline of September to finish the draft. What comes after that, she doesn’t even want to think about. “For now, I’m just working on this book,” she says, “and the book feels like a wall I can’t see over.”

* * *

THAT DESCRIPTION—a wall I can’t see over—might also apply to how I feel about Marfa as I walk up its dusty main street. From a distance, today’s Marfa seems to be a strange composite—a place where down-home, red-state America and elitist, blue-state America meet cute and coexist in a kind of harmonious interdependence.

As I walk, I see things that seem to feed that theory—like two men walking into the post office, one dressed all in black, with a shaved head and a small earring, the other in a huge cowboy hat and blue jeans, with a big bushy mustache and a pistol on his hip.

But at the same time, I’m struck by the sense that there are two Marfas here, one layered imperfectly over the top of the other, like that old sky-blue Ford F250 pickup I see parked in the shade of a live oak, with a surreal, airbrushed depiction of giant bees stuck in pink globs of bubblegum flowing down its side.

Monroe quickly pulls me back to earth—where the real Marfa resides.

* * *

“THIS IS NOT a typical small town,” she says, “There’s not a ton of meth. There are jobs. It’s easy to romanticize this place, but it’s an economy that is running on art money and Border Patrol money, and I don’t know if that’s a sustainable model. You can’t scale that model.”

Monroe is quick to point out that the advantages conferred by Marfa’s unique niche in the art world are part of what makes the little town so livable. That’s why she’s able to shop at a gourmet grocery store, attend a film festival and listen to a cool public radio station. “You know, I don’t think I could live in just, like, a random tiny Texas town,” she admits.

But those things are only part of what has kept her here. The rest has to do with the very real attractions of small-town life—or rather, of life in that dying civic breed, the thriving small town. “This is the only small town I’ve ever lived in,” she says, “and it’s such a unique case. It does have, in its own way, a booming economy, right? And I think that’s not the case for a lot of small towns, where you get a lot of despair and disinvestment and detachment, because there’s not a lot of hope that anything can change or get better. People like coming here, people like living here, because it largely feels good, because it has found this economic niche, so that it’s not a dying small town. And that’s rare, and I think there’s a hunger for that.”

As a volunteer in the schools, the radio station and—of course—the fire department, Monroe is engaged in the community in ways that seem to come naturally here. “Yeah, you can’t be like, ‘That’s not my area. That’s not my role.’ Everybody here is required to step up and help out, and that feels like the norm.”

She has also come to appreciate Marfa’s small-town emphasis on simply getting along. “I wouldn’t say my lesson here has been assuming good faith on the other side or something like that. It’s more diffuse than that—just the sense that when you live in this small place, there is a strong sense of mutual reliance, just one school, one post office, one bank that you share with people who are different from you. And you realize that other people’s opinions are more nuanced.”

Anyway, she says, residents are far more likely to be vociferous about local decisions than national ones—for example, a move to put in parking meters on Marfa’s streets. “People can get way more fired up about that than about stuff that feels somewhat removed from here.”

All in all, Marfa just feels like home in a way Monroe has never experienced before. “It’s a quiet, beautiful life, but not too quiet. I think there’s an element of small-town, mutual care. We’re in it together. That is really nice. I like that my friends include everybody from teenagers to people in their 70s—a much more diverse group, in every sense of the word, than when I was living in Baltimore.”

Ask whether she’s here to stay, however, and her reaction is an involuntary shudder. “Who are you—my dad?” she laughs. “I don’t know. I can’t—no comment. I really have no idea.”

After all, a person who follows her intuition has to keep her options open.

* * *

LEAVING MARFA, I stop for a few moments to take in one of its most iconic images—a famous art installation known as Prada Marfa. If you search for Marfa on Google, it’s the first image that comes up. And a strange scene it is—what appears to be a tiny boutique, with plate-glass windows opening onto a showroom of expensive and stylish shoes and purses, surrounded by nothing but miles and miles of empty scrub desert. Looking at it before I made the trip, I thought it was a wonderfully eccentric encapsulation of what Marfa seemed to stand for.

LEAVING MARFA, I stop for a few moments to take in one of its most iconic images—a famous art installation known as Prada Marfa. If you search for Marfa on Google, it’s the first image that comes up. And a strange scene it is—what appears to be a tiny boutique, with plate-glass windows opening onto a showroom of expensive and stylish shoes and purses, surrounded by nothing but miles and miles of empty scrub desert. Looking at it before I made the trip, I thought it was a wonderfully eccentric encapsulation of what Marfa seemed to stand for.

Here’s the irony—it’s not really located in Marfa at all. It’s about 40 miles away, outside a little town called Valentine. But I suppose “Prada Valentine” just wouldn’t have the same ring.

Photos by Glen McDowell

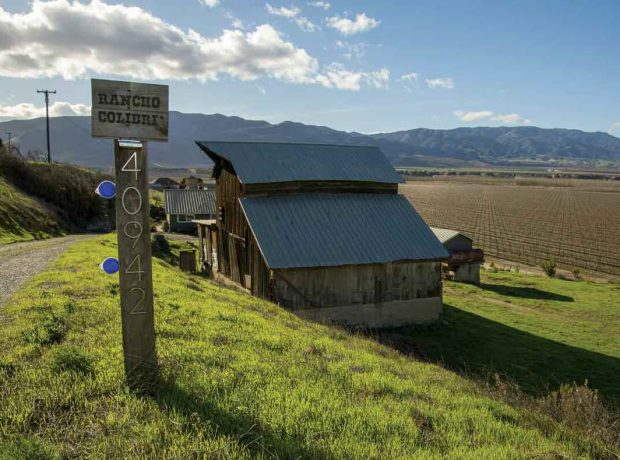

TUCKED AWAY IN a corner of Greenfield, California, a rural town located in the heart of the Salinas Valley, Rancho Colibri sits on a narrow sliver of land bordering a large vineyard with dormant vines.

Standing at the center of the property, wearing scuffed leather boots and Levi’s jeans—the unofficial uniform of most residents in the area—is Jazmin Lopez ’09, who loves to welcome visitors to her “little slice of heaven.”

At 4.2 acres, Rancho Colibri consists of a renovated midcentury house, a large barn where two owls make residence, a mobile chicken coop with squawking residents, sprawling protea plants, a variety of citrus trees that include the unique Yuzu lemon and Australian finger lime, garden boxes made of repurposed materials and a variety of succulents, herbs and native California plants—and of course, the unwelcome gophers that Jazmin is constantly battling.

Rancho Colibri

Although she and her husband, Chris Lopez CMC ’08, took the name for their farm from the Spanish word for hummingbird colibri, Jazmin shares that her father nicknamed her property La Culebra (The Snake) because of its curving, narrow shape. Either way, it’s home sweet home.

Here, with views of the valley floor and the Santa Lucia Mountains, Jazmin is at peace—but don’t let that fool you. She is full of bursting energy, ideas and dreams for her farm. The goal: to one day have a working farm, grow the food she wants and make a living off the earth.

Having grown up in 1990s Napa—a smaller, calmer place than it is today—Jazmin got a taste for the outdoors at an early age. Her parents come from a rural town called Calvillo, located in the state of Aguascalientes in Mexico, and settled in Napa, where they raised four daughters: Jazmin; her twin, Liz; and two older sisters.

Jazmin Lopez ’09 gathering eggs from her portable hen coop

“When they moved to Napa, they brought a little bit of their rancho to Napa.”

The Lopez children grew up on a street that dead-ended at a creek. Childhood in Napa “had a rural feel to it because some of the sidewalks were missing. There were lots of walnut trees we’d go pick nuts from, and we had a surplus of wild blackberries at the nearby creek.”

They also grew up with a rural awareness of the realities of where food comes from that most urban Americans lack. “We had a lot of rabbits growing up. I thought they were my pets. But I soon realized at a young age that the chicken we were eating at our family barbecues was really rabbit.” That’s why, she says, when their neighbor gifted her and Liz each a rabbit on their first communion, she made it a point to tell her parents, “Este no. Este es mi mascota. No se lo pueden comer.” (“Not this one. This is my pet. You can’t eat this one.”)

Once, she remembers, her father brought home a cow that he had bought. Butchering the animal was a family affair that took place in the garage, with Jazmin having meat-grinding duty.

“We grew a lot of our own food. We always had fruit trees, strawberries, tomato plants, chiles, tomatillos—I hated harvesting the tomatillos. Every time I had harvest duty, my hands would turn black and sticky. They’re delicious in salsa, but a pain to harvest and clean.”

As teens, Jazmin and Liz would sometimes accompany their dad on the weekend doing odd jobs like gardening and landscaping, plumbing and electrical work. Jazmin picked up the basics from these trips—practical skills she’s honed as an adult at Rancho Colibri.

“I’ve always been really passionate about gardening.” With a deft pinch or twist of the fingers, she was always bringing home cuttings to stick in the loamy Napa soil—a habit that her husband says continues to this day.

When it was time for college, the twins separated—Liz off to Bowdoin College in Maine and Jazmin to Pomona College. Today, as she sits in her living room, where a white and brown cowhide adorns the hardwood floors her father helped install, Jazmin tries to recall why she never worked at the Pomona College Organic Farm or visited the nearby Rancho Santa Ana Botanical Gardens.

“It’s almost like I put it on hold,” she says adding that academics at Pomona were rigorous enough to demand most of her time and effort. An international relations major, she also felt pressure to follow a certain kind of career path. There’s no regret in that self-reflection. After all, she recalls college as four years to focus on her academics and try new things.

After Pomona, Jazmin accepted a yearlong Americorps placement at a legal-rights center in Watsonville that provided free legal services for low-income people. She liked the work, so after completing the Americorps program, she moved to Oakland—just a few hours north of the Salinas Valley but a world away—to work for a successful criminal immigration lawyer.

There, despite the joy of living with her twin sister and seeing friends who lived in the area, Jazmin soon came to a hard realization: City life was not for her. “It was easy to feel lost and insignificant in such a densely populated area,” she says. “I also missed being able to be outside and feel connected to nature.” She pauses and continues softly, “I don’t know. At times, it just felt overwhelming.”

Trusting her instincts, Jazmin left the city for the countryside with a feeling of coming home.

Located in the town of Gonzalez, off the 101 freeway, family-owned Pisoni Farms grows wine grapes as well as a variety of produce. For the past three years, Jazmin has worked there as compliance and special projects manager. In the office, Jazmin has an unobstructed view of the fields immediately to the south and west and the mountains that form the valley—a gorgeous view she doesn’t get tired of.

Eggs packaged with the Rancho Colibri label

Inside her mud-speckled Toyota Corolla, Mexican rancheras are playing at a low volume, background music as Lopez expertly maneuvers the car through clay mud to a paved two-way street. As she drives past fields with budding greenery, she explains one project where she was tasked with measuring the levels of nitrate in the soil to ensure efficiency in the use of fertilizer. Turning onto another dirt road, she parks her Corolla alongside another project that she oversaw—dozens of solar panels waiting to harness the power of the sun.

Jazmin’s days at Pisoni are always different, full of projects that balance office work with being out in the fields. Off the top of her head, she mentions a few recent projects she’s proud of, including the solar panels, which she researched and helped install on the farm, and getting to work with local high school students who helped test water moisture in the soil. “I love working in agriculture, so when I have the opportunity to encourage kids to learn more about the industry, I invite them to the farm. I like to expose them to how diverse this industry is—there are a lot of opportunities.

From the solar panels, Jazmin spots a familiar face on a tractor down the fields and sends a friendly wave. She seems to know almost every worker. Switching to her native Spanish, she’ll flag them down to ask them about their families and how the day’s work is going. Do they have any questions? Can she help them with anything?

After a short 10-minute drive to one of Pisoni’s vineyards, we see a small group of eight to 10 workers pruning dormant grapevines by hand, one by one—special care that they say makes for better-tasting wine. One of the older men, Paco, without missing a beat from deftly pruning branches, starts to wax poetic about la maestra Lopez—she’s a teacher, he says, because she gives them important training and workshops and, he adds, she’s just a “chulada de mujer” (a wonder of a woman).

“I get along with my co-workers,” she says. “I’ve had some of their kids come shadow me for a day. We bump into each other at the supermarket. We go to their family parties when they invite us. It brings a lot more meaning to my work, and it makes me feel like I’m a part of something bigger.”

Although it’s not totally unusual to see women in the California’s agriculture industry, her boss Mark Pisoni, the owner of Pisoni Farms, says it’s still not a very common sight. “Pomona should be very proud of her. Her diverse skill set is huge—for us, it’s amazing. We’re all called to do what’s required to be done, and she just jumps in.”

Back at Rancho Colibri, the cold Salinas winds are picking up, but the hens and rooster remain unbothered as they cluck and crow in their chicken coop. A two-story affair covered by chicken wire, the coop was designed by Chris (hand-drawn on a napkin) and built by Jazmin in her basement, where the shelves are stocked with tools and supplies that would give any hardware store a run for its money.

Lopez attending to the beehives on the Pisoni Vineyard

The coop she says proudly, is portable. It can be picked up and carried to a fresh spot of grass. With a grin, Chris says Jazmin wishes she could do it all—build the coop and lug it herself—but Jazmin grudgingly cedes that job to her stronger husband. She, however, remains the builder in the marriage.

Chris, who recently launched his campaign to succeed his mentor as Monterey County supervisor, came home one day needing to build a podium for a rally he was holding the following day. With w a gentle scoff at her husband’s building skills, she came to his rescue. With scrap wood found around their farm, she designed and built her husband a rustic podium—all in one hour.

Jazmin admits that they had nearly given up their dream of buying a home because there were few, if any, properties that fit their budget in the area. As the housing crunch in the Bay Area and the East Bay pushes people out, it’s created a trickle-down effect that has increased property prices in small towns like theirs. In addition, local policies are in place to preserve farmland, explains Chris. There’s a big push not to subdivide under 40 acres.

Almost by chance, Chris found their farm for sale, but the house was in bad shape, unlivable really, and in dire need of some tender love and care. Jazmin—who admits to being a fan of HGTV’s Fixer Upper, a home remodeling show—was not only undaunted; she was inspired. After fresh coats of paint, new floors and windows, new toilets and the coming together of family and friends, Rancho Colibri was born.

Upstairs, the living room’s glass doors open to a deck that overlooks the valley floor and beautiful Santa Lucia Highlands where Pisoni Farm’s vineyards are located. Jazmin, a newly minted beekeeper and a master gardener, has introduced beehives, an insectary and a new orchard of her own design to Pisoni’s vineyard.

Jazmin still has a list of projects around the farm, but the place already has the indelible stamp of the Lopezes. A small hallway table with an odd assortment of jars is both a décor element and station for her kombucha tea fermentation. Midcentury modern furniture, bought used and restored by Chris, dots the four-bedroom home.

With her roots firmly planted in the soil, Jazmin is happy.

In early fall, she started a prestigious program she’s had her eye on since the first year she started working in agriculture as a grower education program assistant for the California Strawberry Commission. She’s part of the new cohort for the California Agricultural Leadership Program, a 17-month intensive program to develop a variety of agricultural leadership skills.

“I tend to be on the shy side, and when I attend meetings that are ag-related, I’m in a room full of older white men, and I lose my voice. I don’t feel comfortable speaking up. And even though I know I bring a different perspective as a Latina in agriculture, there’s still that fear that I haven’t been in this that long, that I’m not an expert in this.” The program is challenging her not just to find her voice but to own it.

“I hate public speaking—I can do it, but I avoid it when possible. That’s one thing this program is pushing me to do—to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. It’s a really big deal for me because I want to develop into an individual, a Latina who is able to speak up and share her perspective. It’s a privilege getting to participate in this program.”

Jazmin’s drive doesn’t stop there, however. On top of her full-time job at Pisoni, supporting her husband’s campaign for county supervisor, the never-ending list of chores and home renovation projects on the farm, she’s also just deeply committed to giving back.

For the past few years, Jazmin has been a volunteer with the Make-A-Wish Foundation. As a Spanish-speaking volunteer, she gets called on to interview Latino families to find out what wish a child wants to see come true. “Make-A-Wish does a good job of making families feel special. A lot of the families I have interviewed are farmworking families or recent immigrants. When they get the red-carpet treatment and see a big black limo show up at their apartment complex, it just shines a light of positivity during a dark time.”

Jazmin also recently joined the board of nonprofit Rancho Cielo in Salinas, an organization run by alumna Susie Brusa ’84 that helps at-risk youth transform their lives and empowers them to become accountable, competent, productive and responsible citizens.

Lastly, Jazmin is a Master Gardener volunteer through her local UC Master Gardener Program. Through this program she provides public gardening education and outreach through various community workshops, activities and on the web.“

For a normal person, this might seem daunting, but as Chris says, “Jazmin is a superwoman.”

For Jazmin, making the time for what she loves to do is no chore at all, and Rancho Colibri is the battery pack that keeps her going.

The first two years of living on their farm was a lot of “trial and error” for Jazmin who would walk around the farm to discover what plants grew on the property. Since then she has learned to distinguish the invasive weeds like shortpod mustard from the native plants and is on the offensive to get rid of the invasives.

“She used to have this little hand pump and walk around the farm, so I got this big pump that hooks up to the battery of this Kawasaki Mule,” says Chris, who explains he drives the small vehicle with Jazmin hunched next to him spraying the weeds. “The neighbors think we’re crazy because I’ll be driving as slow as possible and she’ll be hitting these little things at the base. The neighbors ask why we don’t just boom spray and kill it all and then bring back only what we want, but Jazmin is very passionate about the local flora and fauna.”

“She used to have this little hand pump and walk around the farm, so I got this big pump that hooks up to the battery of this Kawasaki Mule,” says Chris, who explains he drives the small vehicle with Jazmin hunched next to him spraying the weeds. “The neighbors think we’re crazy because I’ll be driving as slow as possible and she’ll be hitting these little things at the base. The neighbors ask why we don’t just boom spray and kill it all and then bring back only what we want, but Jazmin is very passionate about the local flora and fauna.”

Looking at her farm, Jazmin adds, “I’ve never owned this much land before, you know? It’s exciting, and I want to take care of it the right way.”

This coming year alone, they plan to install an irrigation system around the farm so they can plant more things further away from the house and expand their garden, to which they want to add hardscaping. They’ll also continue the offensive against invasive weeds and the gophers. “The garden around the house—I have it all designed in my head,” Jazmin says. “I know exactly how I want it to look and the purpose I want it to serve. On the weekends, I take either Saturday or Sunday, or both, to just work on it and make progress.”

They also plan on building a granny unit for Jazmin’s parents when they retire. “I really think they would enjoy living here in their retirement,” she says. “They could have some chickens and make some mole. That’s another project to figure out this year.”

The more Jazmin learns about her farm, the more she wants to do it all. “I want to have a small fruit tree orchard; we want to have a small vineyard to make sparkling wine with our friends; we want to have a cornfield. We want it all.”

“We’ve put a lot of our time and heart and soul into it, and it’s just the beginning. We have so many dreams for our little ranchito, our Rancho Colibri, and I can’t wait to see what we end up doing with it. I can guarantee you that in five years, it’s going to look completely different.”

Kaunakakai, Moloka’i, Hawaii

“I was born on another Hawaiian island, Maui, but my stepfather is from Moloka’i, so I moved there when I was 7, and that’s been home ever since. It’s a very close-knit community. You grow up knowing almost everyone. Everyone knows you; they know your parents; so everything you do is a reflection on your family. The economy is not so great. A lot of people actually sustain themselves through gathering what’s available. We have fish. We also have axis deer, though they’re not indigenous. I do some deer hunting with my dad. This photo is of one of my favorite places. It’s a fresh-water spring—what we call a pūnāwai—that my dad and his best friend restored as a nursery for baby fish. It’s really cold, but it’s nice for swimming. On the other side of the bank is a traditional fish pond—the kind we call a kuapa. It’s about 800 years old. Coming from that setting to a place like Pomona was pretty intimidating at first. I was less politically aware than most people here, so coming here was pretty eye-opening. I tell people I feel like I grew up on a rock. I’ve gotten used to California’s faster pace, but I really miss my family and Hawaiian food and being close to the ocean all the time.”

Orangefield, Texas

“My community is pretty small. We have a gas station, a fire station now—that’s new—a school and a small grocery store. The lumber industry built my town, but today the main industry is the petrochemical plants along the coast of Southeast Texas and Southwest Louisiana. Most families have at least one member who works there. They call it the cancer belt because there are higher rates of cancer in the area. When I left my hometown, I was kind of like, ‘I’m never coming back here.’ You know—a very typical, small-town person who wants to get out to the big city. But then Hurricane Harvey affected my hometown in the first few weeks after I got here, and that was kind of like a slap in the face. My first thought was that my community really needed me right now, but the last thing they heard me say was, ‘I’m never coming back.’ That really made me think. And then, especially, going back home over break and seeing the destruction, but also seeing the recovery and the ways that my community was coming together and helping each other—that was just a really awesome experience. Maybe that’s not unique, but it’s very special. And I think that’s part of the strong communities these small places have. It’s just that everyone feels so connected, and even if you don’t know each other, there is this connection that you share.”

Soldotna, Alaska

“It’s kind of weird, because there’s a whole bunch of small Alaskan villages in the area, but they lump them together into cities. I live in a log cabin in the middle of the woods, roughly 10 miles outside of town, but I’m considered to live in Soldotna. A lot of the people there don’t want government or neighbors or anyone interfering with their lives, so I guess it’s not very communal. I don’t want to speak for all Alaskans, but people in my town really pride themselves on being independent—being able to hunt and fish and provide for themselves. I really didn’t do any of that—if I had, maybe I’d subscribe more to the Alaskan mentality. But I do feel like I don’t rely on things as much as maybe some other people who weren’t forced to live in that kind of environment. Along with a few Alaskan natives, my sister and I were among the only people of color in my school, so it’s been a big contrast coming here to Pomona. But my experience is so different from that of most other people of color here that at first it was kind of uncomfortable. I’m still not a very social person, so I don’t really participate in a lot of things, but I’ve become more acclimated. When I go back home, I enjoy seeing my family and knowing who everyone is when I go to the grocery store, but I don’t think I would want to go back there permanently.”

Cozad, Nebraska

“Cozad is a town of 4,000 people, give or take a few. The last census was around 2010, and I’m sure we’ve lost folks since then. I was born and raised there. Both of my parents were born and raised there, and their parents came there from other places in Nebraska. It’s a pretty stereotypical small, rural town in the Midwest. The nearest Walmart is in the next town over, so you have to drive like 15 minutes on the interstate to get there. The nearest mall’s even farther than that—an hour away. But it’s a place worth visiting. I ask my friends all the time—sometimes jokingly, sometimes seriously—if they ever want to come visit me in Nebraska, and usually the answer’s no. But it’s a place where people who don’t know you make you feel welcome. If you’ve never been to rural, small-town America, it’s an experience you need to have at least once in your life. I personally prefer small-town living to living here next to L.A, and I often think about going back after getting my law degree. The pace is slower. When you think of California, you think of it being laid back. You think of surfer dudes—or at least I do—and beaches and just a cool, chill pace. But the real slow pace is in rural America, where people aren’t in a hurry to get from place to place. They’re enjoying the day; they’re enjoying talking with people they run into on the street, or when they come into their businesses. They’re catching up. That’s probably one of my favorite parts about small-town living.”

The 2017 La Tuna Fire in the hills above Los Angeles.

Wild Los Angeles? That seems a contradiction in terms, for surely it is nearly impossible to locate nature inside the nation’s second-largest, and second-most-dense city. This metropolitan region, which gave birth to the concept of smog and sprawl—the two being parts of a whole—is now so thickly settled that it is almost fully built out and paved over. In the City of Angels, where even the eponymous river looks like an inverted freeway, there is no rural.

Yet as concretized and controlled as Los Angeles appears, it does not stand apart from nature—any more than do small towns tucked away in remote locales. Consider the natural systems that over the millennia have given shape to this region. They are still at work.

The most obvious of these is manifest whenever the grinding earth moves: Tremors radiate along the Southland’s weblike set of fault lines, an unsettling reminder that we stand on shaky ground.

Even when (relatively) still, the landscape conveys an important message about how we live within and depend on the natural world. While strolling through Marston Quad, for example, look due north, focusing in on Mt. Baldy, which the Tongvan people call Snowy Mountain. The latter name is more evocative and revelatory of that 10,050-foot peak’s role as the apex of the local watershed. It is the source of the alluvial soils on which the College is built and of the aquifer that supplies much of the potable water that contemporary Claremont consumes.

Perhaps the most dramatic signal of just how close Angelenos are to nature, and how compressed is the distance between where we reside and that space we imagine as “rural,” flares up every time a wind-driven wildfire sweeps down canyon or howls over ridge. We have endured too many of these fires over the past decade (unlike Northern California, which has a deficit of fire, SoCal has experienced a surfeit).

Some of these conflagrations have been massive, like the Station Fire (2009: 160,000 acres) and the Thomas (2017-18: 282,000 acres); others have been much smaller, such as the Skirball (2017: 422 acres). Notwithstanding their differences in size, these contemporary blazes follow a historic pattern: Wherever people have gone, fire has followed.

A member of the California National Guard on a rescue mission following the January 2018 mudslide in Montecito, California. (Air National Guard photo by Senior Airman Crystal Housman)

Beginning in the late 19th century, tens of thousands of residents and tourists hopped aboard the Los Angeles & Pasadena Railway’s parlor cars that took them straight to the Altadena station, nestled in the San Gabriel foothills. There, by foot, bicycle or the Mt. Lowe Incline, they headed uphill to frolic in the rough-and-tumble terrain. By the 1920s, with the ability to drive a car to local trailheads or up into the mountains directly, those numbers swelled to millions. Some of those engines sparked. Some of the many visitors smoked. The resulting fires, especially the infernos of the late teens and the 1920s, turned the sky black.

Fires also erupted as housing developments, following rail and road, pressed out toward an expanding periphery. For those with the requisite means, the lure of a quiet suburban arcadia segregated from the disquieting urban hustle, yet situated close enough to commute between family and work, was a powerful magnet. Even as this white flight rearranged the city’s spatial dimensions, class interactions and racial dynamics, it proved incendiary in another sense.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Army-surplus bulldozers leveled large lots for grand homes in the Hollywood hills and Beverly Hills, and furious firestorms erupted. For all its damage, then, the Bel Air Fire of 1961, which consumed more than 16,000 acres and incinerated 484 homes, was not unique. In subsequent years, blazes popped up in and around new subdivisions cut into the high ground above the San Fernando and San Gabriel valleys, and, later still, crackled through upland acreage overlooking the Simi and Santa Clarita valleys. Like the August 2016 Blue Cut Fire that torched portions of the rugged Cajon Pass, shut down Interstate 15, and forced upwards of 80,000 people to flee for their lives, the Thomas Fire disrupted freeway traffic in its furious run from Santa Paula to Ventura to Montecito and drove 100,000 from their tree-shaded homes.

With fires come floods. Punishing winter storms, like those that pounded Montecito less than a month after the Thomas Fire sputtered out, can unleash a scouring surge of boulder, gravel, and mud that destroys all within its path. The resulting death and destruction—horrifying, terrifying—is, alas, also predictable. Since the late 1880s, some Angelenos have cautioned about the dire consequences of developing high ground, of turning the inaccessible, accessible. We have ignored those warnings at our peril—peril that climate change is accelerating as it intensifies the oscillation between drought and deluge, fire and flood.

Further evidence that this most urbanized place is, and will remain, inextricably integrated with wild nature.

Char Miller is the W.M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis at Pomona. His recent books include Not So Golden State: Sustainability vs. the California Dream and Where There’s Smoke: The Environmental Science, Public Policy, and Politics of Marijuana.

March 2018

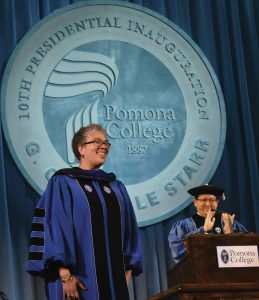

Dear PCM Reader,

Over the past year, Pomona College Magazine has given you the opportunity to walk in lots of different shoes. As a reader, you’ve experienced the struggle to protect an endangered species, the challenge of writing poetry in an alien tongue, the stress of gowning up for a trauma case and the nightmare of homelessness. You’ve welcomed a new Pomona president, explored little-known chapters in College history, witnessed the discovery of a lost civilization—and more. All through people with whom you share an indelible connection as fellow members of the Sagehen family.

My point is this: PCM is there to keep you connected to this special institution and its community of doers and thinkers. Our mission is to inform, entertain and challenge you with Pomona-related stories that make you think, reminisce, learn, laugh, cry, share or simply feel proud to be part of this remarkable college family.

Receiving PCM is a free benefit of your membership in that family. However, the cost of producing an award-winning publication like PCM and mailing it to some 25,000 recipients across the country and around the globe continues to grow, even as budgets tighten. That’s why, three years ago, we launched this voluntary subscription program to supplement our funding and to give you, our readers, an opportunity to help, if you’re so inclined.

Again, let me assure you that you will continue to receive every issue of PCM whether or not you choose to make a gift. This is truly meant to be a voluntary show of appreciation. I know there are plenty of other worthy causes clamoring for your attention, and I would never claim that PCM

needs your help more than those that you’ve already chosen to support (including, I hope, Pomona’s Annual Fund). But if you value what this publication brings to your door with each issue and you can afford to make another gift, we could certainly use your help.

Your generous gift provides direct support for our effort to keep you informed and connected. It also signals that PCM is still a meaningful and valued part of your life. If you wish to make a gift, we’ve tried to make it as easy as possible, using our online giving site.

We are deeply grateful to those of you who have seen fit to show your support in the past and to those who plan to do so this year—again or for the first time. We promise to use these resources wisely to make this magazine even better in the year ahead. In the meantime, we hope you enjoy the enclosed issue on the voices of rural America.

Sincerely,

Mark Wood

Editor

Douglas Preston ’78 in the unnamed river deep in the Honduran jungle

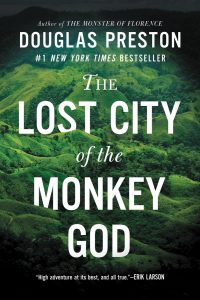

DOUGLAS PRESTON ’78 SAYS he keeps bank hours, writing from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. No dead-of-the-night or predawn creative marathons. The buttoned-down approach might be surprising given the risks he will take to get a good story. In 2015, Preston joined an expedition to see firsthand whether a 500-year-old legend was true. Was there a lost city of immense wealth hidden deep in the Honduran jungle? Indigenous tribes had spoken of this sacred city since the days of conquistador Hernán Cortés. In The Lost City of the Monkey God, Preston narrates an adventure you couldn’t dream up (well, maybe in a nightmare). He and his fellow adventurers found an impenetrable rain forest, deadly snakes, a flesh-eating disease—and the remains of an ancient city rich with artifacts.

Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham talked to Preston about his search for a vanished civilization. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

PCM: What inspired you to go on this adventure?

Preston: I’ve been following this story for a long time. Honestly, I’ve never quite grown up. I’ve always thought that it would be exciting to find a lost city. When I was a kid I was always interested in reading about the discovery of the Maya cities, the tombs in ancient Egypt, the tomb of King Tut. I just loved those stories. But as I became an adult I realized, “Well, all the lost cities have been found, so that one childhood dream is never going to come true.” But then it did come true. So, I guess that’s why I was so intrigued by the story of this legendary lost city. It’s remarkable to me that in the 21st century, you could still find a lost city somewhere on the surface of the Earth. Amazing.

The head of a fer-de-lance, tied to a tree as a reminder of the jungle’s hidden dangers

PCM: What did your family think about your going on this particular adventure, knowing the risks involved?

Preston: Well, I didn’t tell my mother because I didn’t want her to worry, but she found out anyway. But my wife is just as adventurous as I am, and her problem was that she wasn’t going. She wanted to go!

To be honest with you, I didn’t realize just how dangerous this environment was until I was actually in it. Now, I’d been warned. People talked about it and I was fully briefed. But I dismissed those warnings, thinking, “It’s exaggeration. This is for people who’ve never been in a wilderness before.” I assumed they were giving us the worst-case scenario. I didn’t take it all that seriously. Then I entered that jungle environment and realized it was even worse than described.

PCM: Were you afraid when you arrived and you realized just how dangerous it was?

Preston: Oh, I wasn’t at all afraid in the beginning because it was gorgeous. It was amazing to be in a place where the animals had never seen people. They weren’t frightened of us. But where I had the come-to-God moment was when I saw that gigantic fer-de-lance coiled up that first night, highly aroused and in striking position, tracking me as I walked past.

The head of the expedition, a British SAS [Special Air Service] jungle warfare specialist, tried to move the snake but ended up having to kill it because it was so big. The fight was terrifying. That snake was striking everywhere and there was venom flying through the air. It was really shocking. After that, I felt a little shaky. I thought, “Well, this is sort of a dangerous environment, isn’t it?”

PCM: Are there many places in the world that are left unexplored?

Preston: There really aren’t. But even today there are some areas in the mountains of Honduras that remain unexplored. The thickest jungle in the world covers incredibly rugged mountains. When you’ve actually been in that jungle, you realize the steepness of the landscape and the thickness of the jungle make it almost impossible to move forward anywhere, except by traveling in a river or stream. You can’t get over the mountains. You just can’t get over them. You can fight with machetes for 10 hours and be lucky to go two or three miles.

And then, of course, there are all the snakes. The number of poisonous snakes in that area is staggering—and you can’t see them.

PCM: Are you in grasslands? What is the terrain like?

Preston: Well, it’s interesting that you mention that. Most of it is really thick jungle, but where there isn’t jungle, there’s high grass. It’s nine or 10 feet tall and it’s very thick-stemmed. It’s almost like wood. It’s the worst stuff to travel through. You hack away at it with a machete and you can barely make any forward movement. There are snakes hiding in the grass. They climb up into it so there’s always the chance of their falling down on you.

Wherever you are, when you move forward after cutting through with machetes, you’re stepping through leaves and debris that are lying on the ground. It’s two feet deep. You have no idea where you’re putting your feet.

So it’s a really frightening thing when you see just how common the snakes are in there.

PCM: Would you talk about places that are unexplored—like the lost city at the site known as T1? What do you think places like these, for lack of a better phrase, do for the human psyche? Specifically, what did T1 do for you as a group? And broadly speaking, what is it about these unexplored places that is important or significant for us as human beings?

Preston: There are layers of answers to that question. The first is that on a personal level, when you’re there, you realize just how unimportant you are. This is an environment that is not only indifferent but is actively hostile to you. It’s important, I think, for human beings to be humbled by nature once in a while.

On a much deeper level, these environments that haven’t been touched by human presence are extremely rare on the surface of the Earth. It’s vital for us to protect them.

Conservation International sent 14 biologists down into this valley, and they set camera traps. They recently brought those camera traps out, and they saw the most amazing animals—animals thought to be extinct, species that were unknown to science, and unbelievably dense numbers of big cats. There are mountain lions, jaguars, margays, ocelots. Apex predators.

And they’re everywhere in that valley. They’ve never been hunted by people. And what they prey on are animals like peccaries and tapirs, which are also heavily hunted by humans. There are so many peccaries and tapirs in this environment that they support a very large number of these apex predators. This is truly a rain-forest environment that is what it was like before the arrival of human beings and in equilibrium. It’s a beautiful thing to see that.

PCM: Did you feel that others in the expedition group were sharing the same sort of response to that experience?

Preston: Yes, I did. We had 10 Ph.D. scientists with us on this expedition. We had ethnobotanists, three archaeologists, an anthropologist, engineers and others. And all of them were deeply affected and impressed by what we saw. They had the scientific background to appreciate it on a deep level. While I was appreciating it on more of a layman’s level, they understood it on a scientific level, and it was extremely impressive to them.

PCM: When you open the book, it begins as an adventure story, but it turns into a history lesson and a biology lesson. Obviously, it’s still an adventure book, but there are many layers to it. You talk about the historic decimation of the population in the New World versus the lack of decimation in the Old World. Is what you put forth something that’s accepted by the mainstream? Obviously, the numbers seem to bear that out, but are other people talking about it in these terms?

Preston: Yes, I would say that the view I presented is the consensus view. However, it is controversial.

PCM: Would you talk about that?

Preston: Everyone agrees that there is a tremendous die-off among the indigenous people of the New World from Old World pathogens. The controversy is what percentage of people died. There are those who say, “Well, we don’t have solid evidence that 90 percent to 95 percent died. All these numbers that the early Spanish give us, they’re very unreliable.” But the doubters have not come forward with their own numbers. They just say it’s all very unreliable.

However, with no event in history are we given reliable numbers, especially that far back. It’s really a question of looking at all the evidence, the confluence of evidence, and coming up with the most reasonable interpretation. And the most reasonable interpretation, which is, in fact, the consensus, is that there was a 90 percent mortality rate from European diseases. That’s just staggering.

Of course, the big question is, “How many people were in the New World before the Europeans arrived? What was the population? We have very good numbers on what the populations were after, but we don’t know how many were there before. And, again, I think the consensus view is that the aboriginal populations in the New World were quite high.

PCM: Your group got quite the negative backlash from the archaeological community. How do you feel about that today? And do you still think those objections are primarily turf battles, jealousy, politics? Would you talk a little bit about that?

Preston (right) and Chris Yoder wading in the unnamed river

Preston: In my book I try to balance some of the legitimate objections with some of the ones that were not legitimate. To put it in perspective, it was a very small group of archaeologists objecting very vociferously.

The Honduran archaeologists who dismissed our findings were individuals who had been removed from their positions following the military coup in Honduras in 2009. The military removed the leftist president and then turned the government back over to the civilian sector, and they had new elections. A leftist government was replaced by a rightist government. In the process, several Honduran archaeologists lost their jobs and new archaeologists were brought in. Some of the dismissed archaeologists did not look with approval on our cooperating with the current government. On the American side, there were several archaeologists who specialized in Honduras who were upset that the discovery was made not by archaeologists but by engineers using lidar, which is an extremely expensive technology unaffordable to most archaeologists. They also objected that the expedition was financed not by archaeologists but by filmmakers. But since my book was published, along with several peer-reviewed papers on the discovery, the objections have ceased.

When archaeologists first heard about the discovery, they initially didn’t know anything about it. There were no scientific publications yet. They heard that a “lost city” had been found, and some reacted with understandable skepticism. But then when the scientific publications started appearing, the criticism ceased. As of now, almost a dozen archaeologists have worked at the site, all from top institutions—Harvard, Caltech—as well as archaeologists from Honduras, Mexico and Costa Rica. When the doubters read those scientific publications and saw the lidar images of the city, they realized, “Oh, wow, this really is a big find.”

The fact is the importance of this discovery isn’t just archaeological. It has stimulated the Honduran government into rolling back the illegal deforestation of this area and encouraged it to preserve this incredibly pristine and untouched rain forest for the future. That might be even more important than the archaeological discovery. Preserving that rain forest is crucial.

PCM: Talk a little bit about that preservation, because you write in the book about the encroaching destruction of these rain forests and jungles. Do you feel that the protection is going to be effective?

Preston: Well, it’s hard to say. Deforestation is a huge problem. The land is being cleared, most of it, not for timbering, not for the value of the logs, but for the grazing of cattle, for beef production. Because of this discovery, the Honduran government has finally taken steps to stop the cutting of trees and the burning of the forests in the area. And also they’ve taken measures to prevent illegal rain-forest beef from entering the supply chains. I was able to show that originally when we went into 2015, some of this rain-forest beef was going to a meat packing company that was selling through a long supply chain to McDonald’s, Wendy’s and Burger King.

Now those three American companies weren’t aware, I don’t think, that they were buying rain-forest beef, because they were buying it several wholesalers removed, through intermediaries. I know that when I brought my evidence to the attention of McDonald’s, they freaked out and immediately sent people down to Honduras and tried to make sure that they weren’t buying rain-forest beef. Obviously, it’s a good business decision not to be accused of being behind the destruction of the rain forest.

PCM: How much of the site has been excavatied, and how many of the artifacts have been retrieved?

Preston: The city of T1 itself probably covers 600 to 1,000 acres. That’s a very rough guess. Only 200 square feet have been excavated. In that area, they took out 500 sculptures from a cache at the base of the central pyramid. There is so much more still in the ground. It’s just incredible. But the Hondurans are not going to excavate the city. They understand, everyone understands, that it’s much better to leave it as is. They’re not going to clear the jungle or anything like that. They’re going to leave virtually all the rest of it as is.

PCM: So much of it remains untouched still, but do you feel that the experts are gaining more knowledge about this culture that disappeared?

A sculpture of a “were-jaguar” found at the site of the lost city

Preston: Yes, this culture is so little known and uninvestigated that it doesn’t even have a name. They’re just the ancient people of Mosquitia. But they had a relationship with the Maya. It’s a very interesting question as to what the relationship was. The city of Copán is 200 miles west of the site of T1. After Copán collapsed, a lot of Maya influence flowed into the Mosquitia region. The ancient people of Mosquitia then started building pyramids. They started building ball courts and playing the Mesoamerican ball game. And they started laying out their cities in a kind of vaguely Maya fashion. But they weren’t Maya. They probably did not speak a Mayan language. They probably spoke some variant of Chibchan, which is a language group connected to South America.

There are so many mysteries as to who these people were, where they came from, what their relationship was to the Maya, and what happened to them. Now, the excavation of the cache hinted at what might have happened to these people, what caused the collapse not only of T1 but of all the cities in Mosquitia. But we still don’t know anything about their origin, where they came from, who they were. And we have only a vague idea of how they lived in this seemingly hostile jungle environment, how they thrived in that environment.

PCM: You mentioned global warming in the context of the flesh-eating disease you contracted, leishmaniasis.

Preston: Two thirds of the expedition came down with leishmaniasis. The valley turned out to be a hot zone of disease. When I got leishmaniasis, of course, I became very interested in it because it’s a potentially deadly and incurable disease. You find it’s suddenly a rather intense focus of your interest! Epidemiologists have predicted the spread of leishmaniasis across the United States. There was a paper that looked at best-case and worst-case global warming scenarios for the spread of leishmaniasis into the United States. Even in the most optimistic, best-case scenario, leishmaniasis will spread across the United States and enter Canada by the year 2080.

In the entire 20th century, there were 29 cases recorded in the United States, and those were right on the border with Mexico. Since then, leish has been found across Texas and deep into Oklahoma, almost to the Arkansas border. It’s a disease that we are going to have to deal with in the future. There’s no vaccine. There’s no prophylactic for it, unlike malaria. It’s transmitted by sand flies which feed on any number of mammals, from rats and mice to dogs and cats. Sandflies are about the quarter of the size of mosquitos. You can’t hear them. You can’t feel them biting. They come out at night. The disease is very difficult to treat.

PCM: How your current health? You mentioned in your book that the disease is coming back, but you haven’t told your doctor.

Preston: It unfortunately does seem to be coming back. This is not unusual for the strain of leish that we all got. I finally photographed the lesion that is redeveloping. But I haven’t sent it to my doctor yet. I just don’t have the guts to do it.

PCM: So what price are you willing to pay for a story? If you’d known beforehand what would happen, would you have still gone?

Preston: Yes, I would’ve.

PCM: You would’ve?

Preston: Yeah, I would’ve. Honestly, as a journalist, I’ve put myself into some dangerous situations, and if this is the worst that’s going to happen to me, I’m probably ahead of the game. I’m lucky. I would do it again. Look, leishmaniasis is not the worst thing that can happen to you. A lot of people are dealing with a lot worse, like cancer and things like that. So I’m doing just fine.

PCM: Would you go back?