In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on a painting by Christy Freeman and how the image both represents and challenges our conceptions of motherhood and reflects the blending of African Diaspora spirituality with Christianity.

In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on a painting by Christy Freeman and how the image both represents and challenges our conceptions of motherhood and reflects the blending of African Diaspora spirituality with Christianity.

Thomas: The belief is that when you are born, everyone has a protector, an Orisha who watches over your head, your “Ori,” like a guardian spirit or a guardian angel. You might have relationships with one or more Orishas, and it is within your power as a human being to cultivate those relationships and to learn the lessons that Orisha has to teach you.

There are many Orisha and Catholic saint correspondences as a result of Africanisms encoded within Christianity. If you see images of Mary, and she’s surrounded by stars and is in this archway full of color, and she’s standing on a rock on the sea, all that ideography is consistent with Yemaya, the ocean goddess who is seen as the ultimate protector and great mother figure. So she may be respected as Mary, but the figure will also be recognized and loved as Yemaya.

Each Orisha can have dozens of paths. There’s Erzulie, a Haitian Orisha or Loa, who corresponds to the Yoruba Oshun and is also related to Yemaya. Erzulie is also connected to nurturing and motherliness, but she is the personification of love and the erotic, so she is seductive, flirtatious, loves jewelry, mirrors and sweets and wants to see people happy. But beneath that sweet façade, there’s a formidable persona. I’m going to show you a painting of Erzulie Dantor, a different side or path of this deity. I’d like to have you respond to the image first, and then I’ll tell you what fascinates me about it.

Chloe: In the heart on the crown, the top reminds me of ram’s horns, giving the sense that this is someone who is tender and warm but also can defend herself.

Thomas: Yes, this is reworking stories about the feminine, about gender, about power, breaking some of those conventional story lines that associate romance with sentimentality and weakness and docility. There’s tension that comes through that might, in other contexts, seem diametrically opposed, but in this figure they are combined. The softness and hardness; the love, the heart, but also the dagger.

Sophie: It feels like a lot more emphasis on the mother figure, but then also there’s a protective quality that I don’t think is in Western portraits. Mary isn’t usually actively protecting the baby and wielding a knife or wielding any sort of weaponry.

Thomas: What do we know as viewers about those images that you’re talking about? Where Mary’s not necessarily on watch, on guard; the child is just in his mother’s arms. How does the story end? Those images of Madonna and child, that’s the beginning of the story. We already know the ending. This is a disturbing image in that this Mary is thinking off script. It’s a stance of agency and aggression, a huge intervention on the narrative and on the established, fundamental, archetypal, Christian narrative, even though it’s still framed as Christianity.

Byron: I have a question about her necklace. I wanted to know: what’s the significance of that as a Christian icon?

Thomas: It’s a heart and what else? What is hanging below the heart?

Chloe: It could be a skull.

Byron: It looks like a nail.

Thomas: It’s silver. Is it a nail, are we agreeing that it’s a nail?

Byron: There is also something that looks like a snake.

Thomas: I’m so glad you brought up the necklace. We need to consider all those possibilities. The snake is an ancient Vodun archetype, not evil but representative of life and transformation. What about the line of that little dagger on the necklace? Where’s the line going?

Renata: It’s going right towards him.

Thomas: It’s going right towards him, right? In this case, Mary’s saying, “Well, I have a knife, too.”

Sophie: The stars in the painting also are evocative for me. It’s like faith of some sort, which maybe is nonsensical or unreasonable, because they also have resonance with anti-faith.

Thomas: In a particularly African-American or African diasporic context, how might you come to be thinking about the stars?

Sophie: A star guide for going home.

Catherine: Using the signs of the stars to move north.

Thomas: To move north because?

Catherine: Out of slavery. To freedom.

Thomas: The stars are the liberation narrative, at least back in the day of enslavement when knowing about astronomy was a useful skill in escaping and moving towards liberation. When I first saw this amazing picture it immediately tweaked my understanding of the character Sethe in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. She commits infanticide when the slave catchers are on her heels. The controversy, the tension in this story is the question: Is this motherhood? I think the painting also asks that same question. What if the knife ends up being something that is protecting the child by keeping it from the attacker who will certainly dehumanize and obliterate its spirit? Sethe says, “I wasn’t going to let them take that child, wasn’t going to let them make that child go through the monstrosity that I went through.” It redefines the terms of motherhood as not only creator but also potential destroyer; nurturer but also warrior. That’s the ultimate extreme case, extreme scenario, but it does bring the idea of the feminine principle into connection with the highest possible stakes of life and death.

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

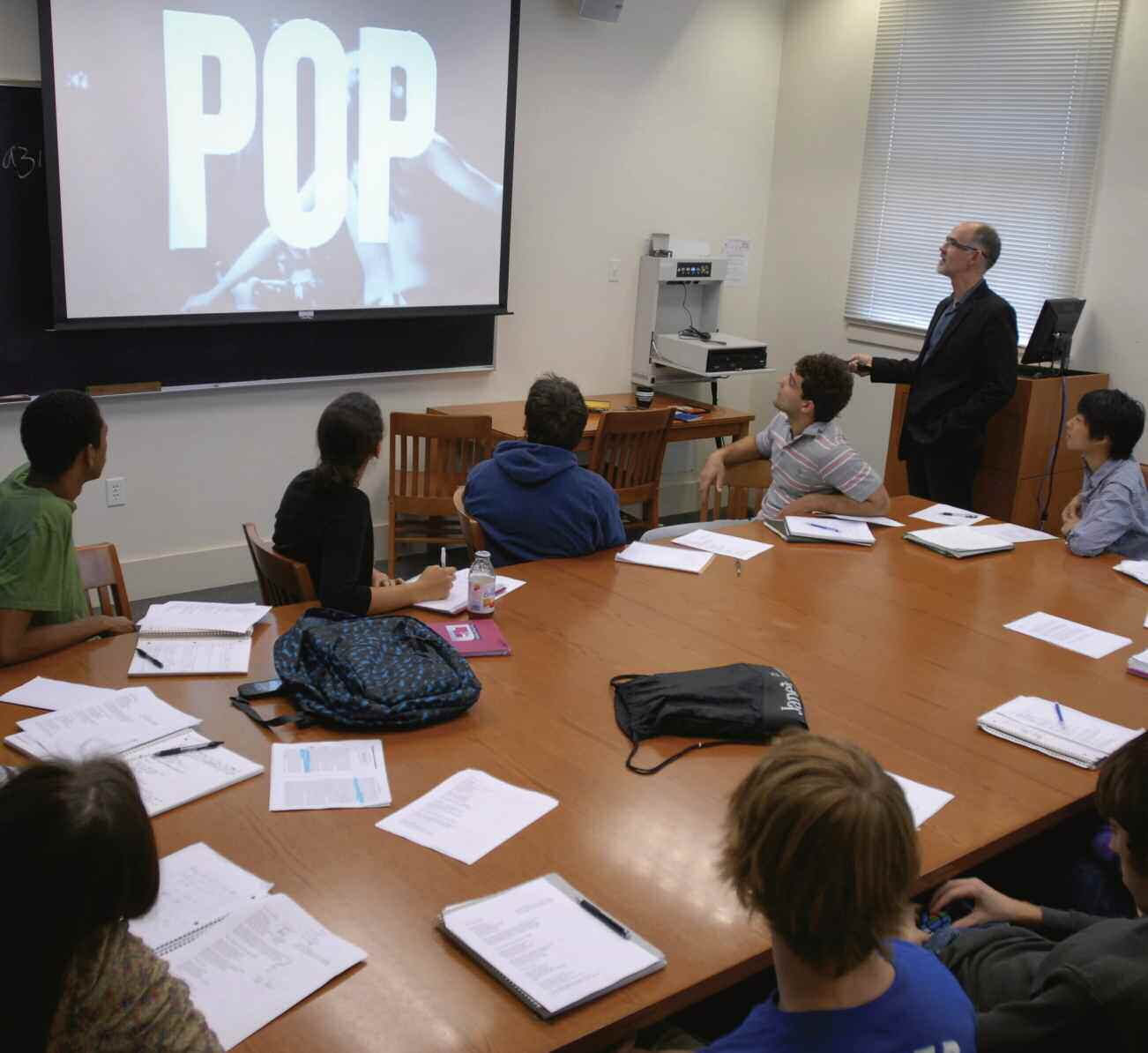

Williams: I want to talk about Berg’s policy arguments, which are controversial. He says we should consolidate all federal food programs into one efficient entity, have a universal school breakfast, reward states to reduce hunger; allow nonprofits to compete for federal funds; give recipients more choice, provide additional services such as job training. What do you think?

Williams: I want to talk about Berg’s policy arguments, which are controversial. He says we should consolidate all federal food programs into one efficient entity, have a universal school breakfast, reward states to reduce hunger; allow nonprofits to compete for federal funds; give recipients more choice, provide additional services such as job training. What do you think? Next, a student-led discussion focuses on I’m Working on That: A Trek from Science Fiction to Science Fact by William Shatner and Chip Walter, and covers topics ranging from wearable computers and biowarfare to cryogenics and virtual reality.

Next, a student-led discussion focuses on I’m Working on That: A Trek from Science Fiction to Science Fact by William Shatner and Chip Walter, and covers topics ranging from wearable computers and biowarfare to cryogenics and virtual reality. Tanenbaum: How many people do you see wearing their earpieces 24 hours a day, seven days a week? I think we’re already there. I want to ask a question that gets at both virtual reality and the wearable computers.

Tanenbaum: How many people do you see wearing their earpieces 24 hours a day, seven days a week? I think we’re already there. I want to ask a question that gets at both virtual reality and the wearable computers. Students in Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval’s Latino Oral Histories class spent the fall semester interviewing Chicano Vietnam veterans as part of a project that will live on for posterity.

Students in Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval’s Latino Oral Histories class spent the fall semester interviewing Chicano Vietnam veterans as part of a project that will live on for posterity.