What’s Behind Walker Wall?

I am writing regarding the history of Walker Wall found on the College’s website. That article reports that the wall “remained unadorned until the spring of 1975, when several students painted ‘Free Angela’ on its inner surface, referring to the imprisonment of Black Panther and Communist Party activist Angela Davis after her conviction on murder conspiracy charges.”

As I recall it, Walker Wall comments started two years earlier, during the 1972-73 school year.

My recollection is that one night just before Founders Day someone spray-painted a phrase on Walker Wall near the pass-through to go toward Honnold Library. The phrase was not particularly clever or political, but it was potentially offensive, perhaps scatological. I was an R.A. for Clark V that year and knew that maintenance would not be able to do anything before alumni were on campus, but I did have access to painting supplies from Zeta Chi Sigma, my fraternity. Betsy Daub ’74, also in Zeta Chi Sigma, allowed herself to be enlisted and our quest became covering over the offending text. We used rollers and white paint to neatly block out the graffiti.

What happened next is somewhat lost to me. Somehow we wound up adding our own phrase on the white surface we had created. As I recall, we had each been considered as possible members of the Mufti crew, and in that spirit we came up with the phrase “Veni, Vidi, Vino” and signed it in some way. That comment stayed for some time and others followed. Although I knew several members of the Pomona administration fairly well, I don’t remember any discussion about the wall, and I don’t think Betsy or I was ever questioned about it.

—Jo Ruprecht ’73

Las Cruces, N.M.

Case for the Liberal Arts

President David Oxtoby’s Aug. 7 letter, directed to alumni of the College, brings up the perennial question “Is liberal arts education still relevant in today’s world?” This question requires a perennial answer: Soon after my graduation from Pomona, I found myself locked into a career in engineering, despite the fact that most of my education had been in art and the humanities. Yet that liberal education proved to be relevant in my unexpected career path. If monetary reward is the main goal, and sadly that is often the case, then one is likely to miss the practical benefits of a liberal arts education, as well as the enrichment of one’s quality of life.

“Liberal education” asks more questions than it answers. This can provide some valuable mental equipment, for answers often become obsolete with time. But if the habits acquired in looking for answers remain with you, and the habit of recognizing analogies is developed, you will have acquired a transferable ability which, unlike rigid collections of facts, can go on helping you generate answers to problems in any field.

—Chris Andrews ’50

Sequim, Wash.

All-Star Mistake?

I have to hand it to you. The “Who Did You Get?” article and trading cards in the Summer 2013 edition of PCM are, perhaps, the most offensive thing I have ever seen in the magazine since I graduated in 1972. Quite an achievement.

Please understand, I am not denigrating the achievements of those honored; their accomplishments are noteworthy and deserve praise—but not by implying (if not actually stating) that all the rest of us just don’t measure up.

Not really worthy of calling Pomona their alma mater, and pretty much beneath the College’s concern. Whether you realized it or not—and my sincere hope is that you didn’t—elevating a few graduates to “Pomona All-Star” status relegates the rest of us to just being average. Banjo hitters. Utility players. Minor leaguers. Barely above the Mendoza Line.

That is not how I like to think my college views me. And yet, there it is. At least you deigned to give us the privilege of “round[ing] up a few of [our] Pomona pals” so we can presumably trade cards. I can hardly wait.

Maybe in the Fall 2013 issue you can identify the biggest donors so far in 2013, and the amounts they’ve given. “Who’s gonna come out on top?” “How much did he/she give?” “Can you believe that [fill in the blank] isn’t on the list?” Now I’ll bet that would be a competition the College could really get behind!

—G. Emmett Rait, Jr. ’72

Irvine, Calif.

Baseball and Bytes

Your article on Don Daglow ’74 and his contributions to computer baseball could have been written, without many changes, about me—if I had just been born a few years earlier. Like Don, I loved the All-Star Baseball board game and was an English major. I wrote my first All- Star Baseball simulation using punch cards on an IBM 1620 in my sophomore year of high school in 1974—just three years too late to gain immortal fame!

I also applied at Mattel to work on Intellivision, but here our paths diverge, for alas, I was not hired. However, my All-Star Baseball game did have one last gasp of life—if you can find an ultra-rare copy of Designing Apple Games with Pizzazz (Datamost, 1985), you’ll find a whole chapter, with source code, devoted to a game called Database-ball.

—John “Max” Ruffner ’81

North Hollywood, Calif.

Fraternity Memories

The letter from Leno Zambrano ’51 in the summer issue of PCM surprised me. I knew Leno as a classmate but I had no clue he was homosexual. I have no recollection of Leno seeking membership in the KD fraternity, of which I was president in the spring of 1951. Not all the men at Pomona in those days felt the need to join a fraternity. Some of them were former members of the military and were beyond the need to join a social fraternity. I don’t know if we had any homosexuals among our KD members at that time, but if we did, they kept it to themselves. We had no policy against homosexuals, per se, in our fraternity mainly because it was never one of the factors we discussed during our consideration of prospective members.

—Ivan P. Colburn ’51

Pasadena, Calif.

I was dismayed to learn from the letter by Don Nimmo ’87 in the summer issue that the fraternity/community Zeta Chi Sigma has ceased to exist. When did this happen, and why? I joined Zeta Chi in my sophomore year—freshmen were not permitted to join frats in those days—and my membership was a significant part of the college experience for me, and not only because of playing pool or watching College Bowl every Sunday. I’ve mentioned Don’s letter to other alumni from that era and am assured that I’m not alone in wondering what happened.

—Steve Sherman ’65

Munich, Germany

Alumni and friends are invited to email letters to pcm@pomona.edu or to send them by mail to Pomona College Magazine, 550 North College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711. Letters are selected for publication based on relevance and interest to our readers and may be edited for length, style and clarity.

Q: What’s the philosophy behind moving sculpture?

Q: What’s the philosophy behind moving sculpture?

Teamwork

Teamwork The latest from Chandra, author of the bestseller Sacred Games, is

The latest from Chandra, author of the bestseller Sacred Games, is  Ved Mehta ’56, the author of 27 books and many articles, has released

Ved Mehta ’56, the author of 27 books and many articles, has released

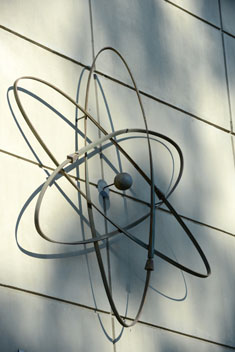

Commissioned for Pomona College’s new math, physics and astronomy lab back in 1958, the bronze atom sculpture facing College Avenue was designed by noted sculptor Albert Stewart, whose work adorns civic buildings nationwide, including the U.S. Mint in San Francisco. Before his death in 1965, Stewart created counterparts for the atom for the facades of Seaver North and South, with an image of cell division for biology and an array of particles for chemistry.

Commissioned for Pomona College’s new math, physics and astronomy lab back in 1958, the bronze atom sculpture facing College Avenue was designed by noted sculptor Albert Stewart, whose work adorns civic buildings nationwide, including the U.S. Mint in San Francisco. Before his death in 1965, Stewart created counterparts for the atom for the facades of Seaver North and South, with an image of cell division for biology and an array of particles for chemistry. Digging Deeper

Digging Deeper

GETTING THE BIG PICTURE

GETTING THE BIG PICTURE