Sad Chapter in Pomona Life

I have been inspired to write you on the subject of gays at Pomona College by the request of Paul David Wadler ’83 to save Pomona’s LGBT history (Letterbox, Spring 2013 issue) as well as by the article in Harvard Magazine, March-April 2013, on “Litigating Gay Rights.”

I graduated from Pomona College in 1951. I was one of the first Fulbright scholars from Pomona. Pomona had a deeply homophobic culture. I was rejected for membership in the fraternities because I am gay, even though I had had no sexual activity to that point. Their rejection stigmatized me throughout the remainder of my time at Pomona. I was then a fervent Catholic, and I internalized their rejection. I felt that I had an illness which the fraternity men were right in not wanting to have around them. My reaction was that it was up to me to find a cure for my homosexuality.

(At the time I was president of the Newman Club for Catholic students. When I told the chaplain that I was gay, even though still without sexual activity, he insisted I resign.)

I found it impossible to find a cure and concluded I could not go into college teaching because I felt the homophobia I had experienced at Pomona would be hellish to endure on a college faculty.

I felt it was impossible to come “out” at Harvard in 1956, and so I stopped studying for my qualifiers and left with a master’s degree. I could not think of a better solution.

I am deeply concerned with the welfare of gay students at Pomona. Do all the fraternities admit gay men? Or is there still a “gentlemen’s agreement” to exclude them from some?

I would appreciate seeing Pomona College Magazine publish an article or more on gay Pomona men and women as rightfully belonging to the Pomona family.

—Lino Zambrano ’51

What Became of Zeta Chi Sigma?

I was accepted by the fraternity Zeta Chi Sigma second semester of my freshman year (that would be 1984). I remained a member throughout my Pomona career. We were coed; for most of my time in said institution women comprised 60 percent or more of our membership.

I also shared the statistic with my best friend as one of the two heterosexual males. In 1986 we changed the designations from fraternity to community and from brothers to siblings. My predecessor as president, a wonderful man named Michael Butterworth ’86, proposed this and we joyously embraced the idea. After his graduation I became president and continued the tradition.

Zeta Chi had history. It started in the early ’60s as the frat for those who couldn’t get into any other frat. Then it was the theatre frat. Then it was the drug frat. Then it was the gay frat (my era).

In my time, it was a collection of wonderful people. We proudly proclaimed ourselves as “siblings.” And we encouraged other students to join our all-inclusive community. Sadly, Zeta Chi no longer exists. I sincerely hope the spirit continues.

—Dan Nimmo ’87

Agonizing Decision

Bill Keller’s [’70] New York Times March 27, 2013, blog on the topic of abortion, titled “It’s Personal,” demonstrates the value of the liberal arts education that Pomona offers (keller.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/27/its-personal/?hp). It matters not if one agrees with Keller’s position, only that one recognizes and admires his ability to think hard, and then to express his thoughts with clarity and passion.

He acknowledges that his remarks are not “likely to satisfy anyone who can reduce abortion to a slogan,” and then he uses his own and his wife’s personal experience, as well as the experience of hundreds of readers who have written to him, to reach the conclusion that abortion, as a matter of law and politics, is a personal decision, “not a decision I would entrust to courts and legislatures, even given that some parents will make choices I would find repugnant.”

Pomona helped Keller learn to think hard. Pomona taught a lot of us to think hard. It continues to do so. Thank you, Pomona.

—Tom Markus ’56

New Ways in the U.K.

President Oxtoby’s reflections on Cambridge (“Autumn in Cambridge,” spring issue) were illuminating, but I do not agree there is less staff-student interaction than at Pomona—just not in the middle of a lecture.

He may also have observed that social class is no longer uniquely rigid in England, as the haute bourgeoisie find when trying to place their child in Eton or Cambridge. Old connections no longer work and the likes of Eton choose the bright offspring of Shanghai textile magnates rather than the “nice-but-dim” sons of aristocratic alumni.

The same is true of our leading universities and Cambridge would not dare show the kind of bias towards “legacy” students that is routine in American Ivies, hidden or otherwise.

—John Cameron ’64

Musical Memories

The Class of 1953 gathered for its 60th reunion on Alumni Weekend and reveled in nostalgia. At our Saturday dinner, Don Shearn and I served as emcees. When Don approached the mic wearing a measuring tape around his neck, he was heckled.

The evening included a video about classmate Frank Wells. Made by Disney colleague Jeff Katzenberg, the video was shown at Frank’s memorial following his death in a helicopter accident in 1994; it illustrated his remarkable achievements, from surviving an airplane crash at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro during his Rhodes Scholar years to his attempt to climb the highest peak on each of the seven continents.

I shared more nostalgia from Hail, Pomona!, an original musical which was presented by alumni, students and staff during Pomona’s Centennial celebration in 1987-88. I read the lyrics of two songs, composed by Dan Downer ’41. Here is a sample:

On the Alluvial Fan

When we came to Pomona,

our mission was clear,

We had only one thing on our minds.

To become educated and quite liberated

With knowledge to help us to find… a man.

I partied up on Baldy at the cabins of frats,

And attended sneak previews at the Fox.

I danced at the Mish and had dates at the Coop

And had long philosophical talks.

I cut classes and went swimming

at the beach in Laguna,

But I only found out how to get a tan.

And then suddenly it happened

And I learned about love, out on the alluvial fan.

When he asked me if I’d like

to go out to the Wash,

I finally began to have hope.

I could tell by the way that he asked me this

That I wasn’t supposed to bring soap.

He said we would look at the stars out at Brackett

And he knew that I would know

what that would mean.

But if a girl’s going to learn

about love any place,

At least in the Wash it is clean.

On the alluvial fan with a Pomona man

You must remember one thing,

That senior or frosh, just a trip to the wash,

Might make those wedding bells ring.

Now I have what I came to Pomona to get,

A degree in fine arts and a man.

But I didn’t get either from my courses at Seaver,

I learned on the alluvial fan

In the Wash as a Frosh I learned about love

Out on the alluvial fan.

The lyrics of the second song resonated with a class that graduated 60 years ago.

Look Where I am in the Book!

As I looked through my mail one morning,

Something hit me without any warning.

Wasn’t something I read that hit me,

But where it was that quite undid me.

Look where I am in the book!

I’m nearing the front of alumni news notes,

In the back of Pomona Today.

I don’t know how it happened, it just couldn’t be,

I’ve moved up three pages since May.

Every issue ages me nine or ten years.

I’m face to face with one of my fears.

It’s an unhappy fact in each issue,

The classes ahead get much fewer.

While just behind there’s a long growing line,

Let’s sing one more chorus of Auld Lang Syne.

But the news of my friends is a comfort to see,

I can watch them getting older with me.

Look where I am in the book!

—Cathie Moon Brown ’53

Editor’s Note: Hail, Pomona!, The Show of the Century was produced by Cathie Brown and Don Pattison, former editor of Pomona Today.]

I had been looking forward to joining the Class of ’78 for our 35th Reunion, but, unfortunately, I was unable to attend. The celebration, however, has given me cause to reflect upon my Claremont days.

I am eternally grateful for the outstanding music education that Pomona provided, a foundation that has served me well in my career as a performer, conductor and educator. Equally important and influential was the schooling I received as a result of interaction with amazingly talented classmates.

The early departure of David Murray in 1974 might have left a tremendous void in Claremont’s music scene were it not for a group of remarkably accomplished singers and players whose eclectic interests and ardent collaborations contributed to a vibrant and supportive atmosphere for music and musicians.

Not to diminish the training I received from such gifted teachers as Kohn, Kubik, Russell, Ritter and Reifsnyder, but I will always be indebted to the brilliant and passionate student musicians I encountered during my years in Claremont. I am thankful for having had the opportunity to share music-making with the likes of Dean Stevens ’76, Bart Scott ’75, Richard Apfel ’77, Carlos Rodriguez, Julie Simon, Bruce Bond ’76, Anne McMillan ’78, Mary Hart ’77 and Joel Harrison ’79, as well as Dana Brayton ’77 and Tim DeYoung, who left us too soon. I hold fond memories of these good people.

Gratias multas to them and to those I may have forgotten. Little Bridges, the Smudgepot and the Motley still resonate with their great music and generous spirits.

—Jim Lunsford ’78

Spelling (Sea) Bee

I have just finished reading the Fall 2012 issue of your excellent magazine. I enjoyed it, but am pained by an error. In the obituary of a classmate of mine, Armand Sarinana on page 59, he is listed as having been a Navy “See” Bee.

Actually, these men belonged to a Construction Battalion, hence the name, based on the initial letters, C.B., so they were known as “Seabees.” Their symbol was a very angry bee, in a sailor hat, holding a hammer and a wrench in two of his “hands” and a machine gun in his other “hands.” One of their many exploits was constructing aircraft landing strips on newly-captured islands.

Obviously, I’m a nit-picker. Must be the English classes I had at Pomona!

—David S. Marsh ’50

We freshmen on the Pomona-Pitzer baseball team have a new position to add to our baseball cards: designated foul ball retriever. Every year, the new guys assume the job, as a collective unit, of making sure every single ball that leaves Alumni Field gets back safely into the umpire’s pocket.

We freshmen on the Pomona-Pitzer baseball team have a new position to add to our baseball cards: designated foul ball retriever. Every year, the new guys assume the job, as a collective unit, of making sure every single ball that leaves Alumni Field gets back safely into the umpire’s pocket. Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

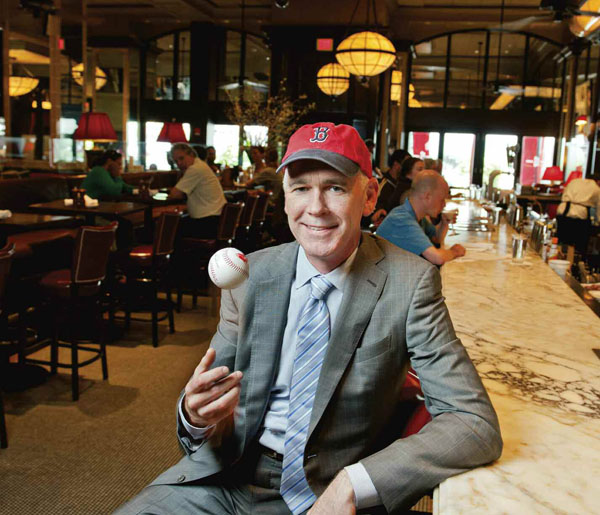

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood.

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood. In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”

In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”