The Class of 2020 gathers on the steps of Carnegie Hall.

—photo by Jeff Hing

Welcome New Alumni Association Board Members

47 hearty chirps to Jordan Pedraza ’09 as she steps into her new role as president of the Pomona College Alumni Association. On October 2, to kick off the first meeting of the 2016–17 Alumni Association Board at the Seaver House, Pedraza welcomed four new at-large members to the Board: Mercedes Fitchett ’91, Nina Jacinto ’08, Ginny Kruger ’53 and Don Swan ’15. Pedraza also shared her goal for the board this year—to foster “the three Cs”:

Congratulations, Jordan, and welcome new board members!

The Alumni Board is a group of dedicated volunteers who lead alumni engagement efforts and serve as conduits between the on-campus and off-campus Pomona communities. To see the roster of current board members and learn how to get involved, visit www.pomona.edu/alumni/alumni-association-board.

Calling All Lifelong Learners

Join

Ever wish you could go back to class?

The new Ideas@Pomona program curates the best academic content from around campus and the Pomona community to ignite discussion, share ideas and highlight daring research. To take part, join the Ideas@Pomona Facebook group at facebook.com/groups/ideasatpomona. Not a Facebook user? Check the Pomona College YouTube channel for videos and watch your email and this bulletin board for updates on development of a web-based home for Ideas@Pomona content.

Settle Into Fall with New Pomona Book Club Selections

Fall semester is well under way and it’s time to head back to the library with Pomona! With a national election on the minds of many Sagehens, we’ve asked faculty across campus to recommend books that approach crucial political and cultural topics in insightful ways. Fall and early winter selections include:

October

The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America by George Packer

Recommended by Associate Professor of Politics Susan McWilliams

November

Founding Brothers by Joseph J. Ellis

Recommended by Warren Finney Day Professor of History Helena Wall

December/January

The Plot Against America by Philip Roth

Recommended by Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck

To join the Book Club and access exclusive discussion questions, faculty notes and video content, visit www.pomona.edu/bookclub.

Career Connections at Pomona College

Matt Thompson ’96, Wayne Goldstein ’96, Bill Sewell ’95, Jeremiah Knight ’94, Paulette Barros ’11

Pomona College Career Connections kicked off its year of programming at Claremont Graduate University’s downtown LA campus on September 27 with a panel of Sagehens discussing careers in advertising, digital media and virtual reality. Panelists included Paulette Barros ’11, Wayne Goldstein ’96, Jeremiah Knight ’94, Bill Sewell ’95 and Matt Thompson ’96. The Pomona College Career Connections program fosters meaningful relationships for Sagehens in their professional lives and provides opportunities for volunteers to help current students as they discover different career paths. To learn more about the Career Connections program and events, visit www.pomona.edu/alumni/careerconnections.

Avery Bedows ’19 demos technology from his virtual reality startup Altar Technologies, Inc.

Give your gift and tell us why you are committed to Pomona at www.pomona.edu/give.

There’s another Oxtoby who has had a Pomona presence for the last 13-plus years. Claire Oxtoby has a view of the College and a college president’s role unique to that of a life partner. But she has been a participant at Pomona, not just an observer.

There’s another Oxtoby who has had a Pomona presence for the last 13-plus years. Claire Oxtoby has a view of the College and a college president’s role unique to that of a life partner. But she has been a participant at Pomona, not just an observer.

Eschewing the somewhat archaic title of first lady—too ceremonial, she says—Claire prefers to think of herself as a doer. She is a familiar face in the community, whether meeting with students, talking to staff, attending College events like concerts in Little Bridges or a lunchtime talk in Oldenborg, traveling with the president on Pomona-related trips or auditing a history of photography class.

Claire has felt like part of the fabric of the College, with all the challenges and triumphs woven through what she calls an exciting and dynamic place. Literally living and breathing Pomona 24/7 has meant the occasional awkward moment. Like the student who rang the Oxtobys’ doorbell, shower bucket in hand and towel slung over his shoulder, asking if he could shower at their place, because Wig Hall was flooded, and there was no hot water. Claire invited him in to talk, wielded the power of a president’s wife, and put in a call to facilities.

Sometime back, Claire read an Inside Higher Ed article that talked about how not to be a toxic asset as a college president’s spouse. Laughing, she says she didn’t find the don’ts all that useful, but the dos were. Simple things, she says, like being friendly, approachable and helpful. She has played the role of a bridge builder, she says.

“David has a contract with various expectations, and how the College does as a whole is the metric that he is measured by. But for my job there are no metrics, so it’s really about just fitting in and trying to be helpful or make connections in different places,” Claire says.

Stories she’s heard from students have sometimes led to her connecting them with alumni or a job. She says those personal connections, whether with students, faculty, staff or alumni are among the things she’ll miss most about Pomona.

An early education teacher in Chicago before they came to Claremont, Claire still shares David’s passion for education. It’s something that is positive and forward-looking, she says. Looking back and looking ahead, based on what she’s seen at Pomona, she believes the future is bright.

“It makes you feel good about the world each year when we’re graduating students. They’ve had this experience here, they’ve brought their experiences, they’ve had more, and now they’re going out, and it makes you feel hopeful.”

AP Photos by Rich Pedroncelli

Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia ’99 watches as votes are posted for and against her bill, AB1561, to repeal the sales tax on tampons and other feminine hygiene products. The bill passed but was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown. —AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli

When Cristina Garcia ’99, then a high school math teacher living in Pasadena, was nominated by her siblings to move back to Southeast Los Angeles to care for their ailing parents, she didn’t think twice about taking on her new role as caregiver. Moving back home when her family needed her was an easy decision. Garcia says she’d do it again in a heartbeat.

But resettling less than a mile away from her parents’ home, she suddenly found herself back in the heart of Bell Gardens, the city she thought she had left for good.

When she was growing up, her idea of success had followed the same age-old formula familiar to many: Leave your poor hometown, make something of yourself and never look back. And she had done exactly that. After excelling in high school in the mid-1990s, she had left her hometown, known for its high teen pregnancy rates and polluted air, for the tree-laden and book-filled campus of Pomona College. With a double major in mathematics and politics in hand, Garcia thought she was set for life.

“I taught math for 13 years, and I had a pretty amazing life. I got to teach at the high school level and the college level,” she says.

Now she was right back where she had started.

Today, sitting in her district office that bears her current title, California Assemblymember, she recalls the sense of failure that soon enveloped her upon her return home just a handful of years before.

“We had been taught that success was leaving and never coming back to these communities,” she says. “And so I felt like a failure, in a way, coming back and giving up my comfy life that I had.”

It took a heart-to-heart intervention by her younger sister to help her snap out of it. “She said, ‘You have leadership skills and you have a responsibility,’’’ recalls Garcia. “I was like, you know what, I’m going to start going to council meetings and start asking questions, and eventually that led me to ask more questions.”

Garcia started by attending Bell Gardens’ city council meetings, trying to get information about the city budget and expenses. She hit a lot of roadblocks and found disturbing practices. Next door, in the City of Bell, residents were asking similar questions, trying to figure out why their taxes were so high. They, too, were hitting a brick wall, with no answers and no accountability from their elected officials.

Then in 2010, the Los Angeles Times broke one of the biggest corruption scandals to rock the state in recent memory. At the heart of it was rampant graft and theft of city coffers by a cohort of City of Bell officials. Outraged, Garcia joined with other local activists to form BASTA (Bell Association to Stop the Abuse).

“I saw it as an opportunity for change for the whole Southeast [Los Angeles], since the problems that plague these cities are all very similar. A lot of the dysfunction I saw in Bell Gardens was present in Bell and other surrounding areas,” says Garcia.

Largely thanks to the work of BASTA, six Bell officials were recalled. Eventually, they were brought to trial on corruption charges and are currently serving prison sentences. Through this yearlong process, Garcia’s resolve for change never wavered.

Assemblymember Cristina Garcia ’99 in conversation with Assemblyman Ian Calderon of Whittier just before the Assembly unanimously approved her bill, AB1673, which bans lobbyists from hosting fundraisers at their homes and offices. —AP Photo/Rich Pedroncelli

“Failure was never an option, because failure was not an option for my community. I had a sense of responsibility to take our communities back. I thought I’d be there for three weeks, but it was over a year,” she recalls. “Then I was done. I was tired. I thought: I’ve done my part, and my parents are doing better. I can go back to my old comfortable life.”

But by then, that “old comfortable life” was just a mirage.

In 2012 her leadership abilities were called upon again when she was asked to run for State Assembly in the upcoming election. Although she hesitated at first, it was her sense of social responsibility that helped her make the choice.

“We’ve had absent representation for my whole life. I realized I had to sacrifice my comfortable life and become a public figure. I’d been private all my life. I’d been independent all my life. I’d been doing math all my life, so you don’t get to talk to people all the time—and that all changed all of a sudden when I decided I was going to do this. That sense of responsibility has continued to be my guiding principle.”

Social Responsibility

Garcia’s sense of social responsibility was shaped during her time at Pomona College. She came to campus at a time when anti-immigrant sentiment ran strong in California politics. She protested and organized against Proposition 187, which made undocumented immigrants ineligible for public benefits, and Proposition 209, which ended affirmative action in public universities.

“I was very aware of the opportunities and privileges that I had and how different I was from most of my peers back home who didn’t get to go to college or who did get to go to college but didn’t get to have the same opportunities I had at Pomona—personal attention, study abroad, or when I didn’t have money for books, being able to receive a grant for books,” says Garcia.

“It came with a sense of social responsibility. There were a lot of social justice discussions on campus when I was there. I was there as Prop. 187 had passed and Prop. 209 was going on, and Pomona College allowed those discussions to happen.”

That sense of social responsibility continued to guide Garcia well into her career as a teacher, and in her decision to run for the state Assembly.

In 2012, defeating a longtime incumbent, Garcia was elected to represent the 58th Assembly District, which includes the cities of Artesia, Bellflower, Bell Gardens, Cerritos, Commerce, Downey, Montebello, Norwalk and Pico Rivera. She was reelected in 2014 and is up for reelection again this November.

Garcia came into office with the stated goal of making politics more transparent and rebuilding the public’s trust in government, and in 2014, she introduced a wide-ranging package of ethics and transparency measures. Five of these passed and Gov. Jerry Brown signed them into law.

Garcia is proud of that accomplishment, but she’s not sitting back and relaxing. She likes to keep busy.

In her four years in office, Garcia has focused on three areas dear to her heart: good government and reform, environmental justice, and elevating and expanding the role of women in society and government. She chairs the Committee on Accountability and Administrative Review, and she is the vice chair of the Legislative Women’s Caucus.

“I decided that to be legislator, I was going to legislate to empower other women and change that. There’s a lot of work and not enough women, so I want to share the wealth with other women,” she says.

Among her most recent and lauded efforts is the so-called “Tampon Tax,” a bill that would repeal the sales tax on pads, tampons and other menstrual items. Although Gov. Jerry Brown recently vetoed the bill, Garcia is not giving up.

“I am known as ‘Ms. Maxi.’ I am the ‘Tampon Lady’ everywhere I go. ‘Ms. Flo.’ And it’s fine; I take on the jokes because I get to expand on women’s health care. It’s not something to be ashamed of or to see as something that is dirty,” says Garcia with a smile. “It’s exciting to talk to young women. It’s exciting to see it become a national discussion. It’s exciting to see women’s health in a different way, and it’s exciting because it affects our day-to-day life.”

Recently, Garcia also introduced legislation to revise an outdated definition of rape—an issue brought to light after a judge sentenced former Stanford swimmer Brock Turner to six months after he was convicted on three felony counts of sexual assault. Garcia was moved to action after reading the open letter penned by the unnamed survivor in the case.

“Part of getting rid of our rape culture is talking about it, but it’s also about how we define it. … If we’re going to end rape culture, we have to call rape what it is—it’s rape.”

Investing in Government

Although she’s faced a lot of setbacks, Garcia remains undaunted. Picking up lessons from her past, it seems like failure is no longer part of her equation.

When asked what advice she would give a younger Cristina or college students of today, she says simply, “Don’t do it all.”

Another tough lesson learned.

Garcia says she did indeed try to “do it all” as a Pomona student, a habit that she carried over in her first years in the legislature.

“For a while I tried 20 different clubs [in college], but it’s better to find one or two that you’re passionate about and be really good at it,” she says. “This year I’ve pared it down to the basics, things I really care about. So I only have seven bills that I’m working on. They’re a lot of work, but really hands-on and I’m really passionate about them, and I’m much happier about the work that I’m doing.”

Her advice to students: “Find something you’re passionate about and get engaged in it and figure out how you’re going to be engaged. Take on leadership roles like president or secretary.”

And Garcia is helping her constituents of all ages become agents of change. Her annual “There Ought to Be a Law” contest gives residents a chance to submit proposals to improve their community.

Last year, a local fifth grade class invited Garcia to their classroom for a special presentation on the nearly 1.5 million people of Mexican descent who were deported by executive order in the 1930s. “The students felt that history was repeating itself, so they did presentations; they wrote poems and books. They became activists and lobbyists,” she says.

Garcia encouraged the students to enter her contest and they won. Last October, they saw their proposal signed into law by Gov. Brown.

This year, all new public school history textbooks will include information about the Mexican Repatriation Act of the 1930s.

“I’m an idealist at heart,” she says. “I’m an idealist in the belief of the social contract, that in order to have a government that works for us, we have to invest in it.”

That’s a tall order, but Garcia is game. Sitting in her district office, Garcia says, “There are times when I joke: Can I retire now?”

Not for a while, it seems.

Photos by K.C. Alfred

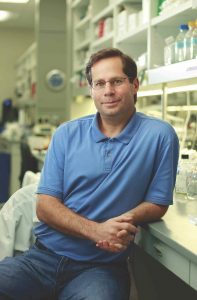

Osman Kibar ’92 has grown accustomed to skeptics. They don’t seem to bother him.

Kibar is the founder and CEO of Samumed, a small San Diego biotech company with new drugs in clinical trials seeking to cure arthritic knees, hair loss, scarring of the lungs, degenerative disc disease and four types of gastrointestinal cancers. Even Alzheimer’s is on the longer-term list of about a dozen targeted diseases.

Samumed’s goals are stunningly ambitious: What Kibar and his team are trying to do is repair or regenerate human tissues through drugs that target the complex system known as the Wnt pathway, which is a key process in regulating cell development, cell proliferation and tissue regeneration.

The potential is so mind-boggling that despite being at least two years from an all-important Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the first of many drugs in its pipeline, Samumed already has raised $220 million in funding and is completing another round of $100 million that values the company at an astonishing $12 billion, making it the most valuable biotech startup in the world.

That eye-popping valuation and the boldness of Samumed’s venture landed Kibar, 45, on the cover of Forbes magazine in May, the featured figure on a list of 30 Global Game Changers that included Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg.

Though Samumed—named for the Zen term “samu,” for meditation at work or in action—doesn’t have a product to sell yet, the confidence of Kibar, his team and key investors has soared on the early results in human trials of the hair loss and osteoarthritis drugs, which appear to show Samumed’s drugs may safely regrow hair and even cartilage.

The potential of the osteoarthritis drug alone is tantalizing to Finian Tan, chairman of Vickers Venture Partners, an international venture capital company that owns about 3.5% of Samumed and is bullish enough to be seeking to take 30% of the current round of funding.

“It doesn’t matter who cures osteoarthritis. Whoever cures it has the potential to be the largest company in the world,” says Tan, basing his calculations in part on the fact that there are some 27 million osteoarthritis sufferers in the U.S alone.

And Samumed is going after far more than fixing worn-out knees with injections instead of surgery. The firm is developing drugs that target a wide swath of diseases, many of them related to aging.

“After all is said and done, if we have just one approval, then we have failed miserably,” Kibar says. “We call our platform a fountain of youth, but piece by piece.”

“After all is said and done, if we have just one approval, then we have failed miserably,” Kibar says. “We call our platform a fountain of youth, but piece by piece.”

Born in Turkey, Kibar came to the U.S. in 1988 after graduating from Istanbul’s elite Robert College high school, which selects only those who score in the top 0.01% of Turkish students on a national standardized test. With a perfect 800 on the math section of the SAT and a 1987 European math championship in his pocket, Kibar had options when it came to college. But he bypassed more internationally famous East Coast schools for Pomona College in part for a climate more similar to that of his hometown of Izmir on the Aegean coast, and in part for the opportunity to attend Pomona on a 3-2 program that allowed him to earn a B.A. in mathematical economics at Pomona in three years, winning the Lorne D. Cook Memorial Award in economics his final year, and a B.S. in electrical engineering from Caltech two years later.

Kibar went on to earn a Ph.D. in engineering at UC San Diego and worked with his graduate school advisor, Sadik C. Esener, to found Genoptix, an oncology diagnostics firm that went public in 2007 and was acquired by Novartis for $470 million in 2011. Kibar also was a cofounder of e-tenna, a wireless antenna company whose assets were acquired by Titan and Intel. In addition, he had a stint in New York as a vice president on Pequot Capital’s venture capital and private equity team.

Samumed, founded in 2008, grew out of a company named Wintherix after legal disputes with Pfizer. It was built initially on the research of a small group of scientists including John Hood, one of Samumed’s scientific cofounders, who recently left to start a company of his own called Impact Biosciences. Hood’s track record is impressive: He created a cancer drug that led to his former company TargeGen being sold for over half a billion dollars.

Kibar’s intellect and energy are unquestioned. Consider that on the side, he is working through the course outline he found online for a Ph.D. in mathematics at Princeton, just for enjoyment. And once, on a lark, he entered an event on the World Series of Poker circuit and won. Betting against him, it would seem, is at your peril. But with goals so lofty, he does have his doubters.

The Forbes magazine cover led to an interview on CNBC that can best be described as skeptical, tossing around words like “too many red flags” and a comparison to Theranos, the medical diagnostic testing startup that went from a $9 billion valuation to being targeted by federal investigators and losing its partnership deal with Walgreens.

It’s a cautionary tale, but Kibar and industry experts say Samumed is no Theranos. As Kibar says with his typical disarming laugh, “First of all, you know the Taylor Swift song, ‘Haters Gonna Hate’?”

“Every big pharma, every small biotech, every academic center—they have been working on the Wnt pathway, trying to come up with a drug that can modulate the pathway in a safe manner,” Kibar says. “It’s been more than 30 years, and every single one has failed so far. So when we come out and say we did it, there is natural skepticism. Without seeing the data, the so-called experts’ reaction in a fair manner is, ‘Yeah, yeah, everybody has tried it. What makes these guys so special that they will have cracked the code?’ So our response to that is: Just look at the data.”

For starters, the company already has been issued dozens of patents by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, has five programs in clinical trials and has begun sharing data with the medical community that shows the hair loss and osteoarthritis drugs appear to be safe and effective in small human trials.

“I don’t think Theranos is a very good analogy for this company,” says Derek Lowe, who holds a Ph.D. in organic chemistry and works in the pharmaceutical industry while writing the widely read drug discovery blog In the Pipeline, which appears on a site maintained by the journal Science. “You can look at the patents and see the types of molecules [Samumed is] working with,” Lowe says. “This is not one of those where ‘we’re going to change the world but you can’t see anything’ companies like Theranos.”

Kibar shrugs off any comparisons to Theranos and its headline-grabbing fall from grace.

“They’re in diagnostics and they never shared their data, so their whole approach was: ‘Trust us, we got this,’” he says. “Being in the therapeutic field, we’re coming up with drugs; we don’t have that luxury. We cannot say, ‘Trust us, we got it.’ First and foremost, we have the FDA. The FDA is not going to take our word for it.”

The FDA is the gatekeeper, and though less than 10% of proposed new drugs ultimately earn FDA approval, the likelihood increases with each step forward in the lengthy process. The next step for Samumed’s most advanced projects, the hair loss and osteoarthritis drugs, is large Phase III studies with thousands of participants. Some 64% of drugs that begin Phase III studies are submitted for FDA approval and 90% of those are successful, according to a study cited by the independent site fdareview.org.

To begin building support in the medical community, last November at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Samumed presented clinical data w from its Phase I trial of 61 patients for a new drug that seeks to regrow knee cartilage to treat osteoarthritis. Animal studies already had shown that injections of Samumed’s compound caused stem cells to regenerate cartilage in rats. The Phase I study focused on demonstrating that the drug is safe in humans, but MRIs and X-rays also suggested a single dose showed what the company called “statistically significant improved joint space width” in the knees of patients who received it. A Phase II study of 445 patients is under way and expected to be complete next spring.

Samumed followed those announcements with a presentation of Phase I data from its trial to treat baldness at the World Congress for Hair Research, and in March presented data from its completed Phase II hair-growth trial to the American Academy of Dermatology. That study of 310 participants showed that hair count in a one-square-centimeter area of one group of subjects’ scalps increased by 7.7 hairs (6.9%) and by 10.1 hairs (9.6%) in another, though the largest increase was in the group that received the lower of two doses. The control group lost hair.

Tan, the venture capitalist known for making an early bet on Baidu, the Chinese answer to Google, sticks to his assertion that Samumed, if successful, could be bigger than Apple.

“I think the potential is unbelievable. With the Wnt pathway, when it eventually is totally controllable, the sky is the limit because it is involved in cell birth, cell growth and cell death,” Tan says. “The key is nobody has been able to successfully manipulate the Wnt pathway safely and effectively. Samumed appears to be doing it in human trials.”

So far, the trials are small, preliminary studies, both Samumed and industry observers note. Since the groundbreaking discovery of Wnt signaling in the early 1980s, no other attempts to modulate it have succeeded, and tinkering with a system that regulates cell development clearly involves risk. In an article titled “Can We Safely Target the Wnt Pathway?” in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, a publication of the journal Nature, Michael Kahn, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine who holds a joint appointment in pharmacy, likened the Wnt pathway to a “sword of Damocles.” Put most simply, targeting the Wnt pathway might cure cancer, but could also cause it.

“It is a death or glory target,” says Lowe, the industry blogger.

That, of course, lends itself to discussion of the high-stakes gamble reflected in the company’s $12 billion valuation. Investors include many with close ties to Kibar, and he says remaining privately held allows Samumed to proceed without shareholder pressure for quick results and requirements for public disclosure in what is by definition a long-haul endeavor. Inter IKEA Group, the retail giant’s private venture firm, has placed the largest bet among Samumed’s mostly anonymous outside investors. The operative phrase is “caveat emptor.”

“Anybody who is investing in an early-stage biopharma company has to be ready for it not to work out, because most of these don’t,” Lowe says. “The hope is just like if you’re developing some great new app: The hope is this is going to turn out to be something big.”

It’s a boom-or-bust world. Kibar and his team know that but remain confident.

“From a technical perspective, we don’t lose any sleep anymore, because we have demonstrated safety and efficacy and disease modification in enough programs that we believe we have already validated the broader platform,” Kibar says. “In terms of funding, we’re also in a fortunate position in that we have all the money we need to bring these programs all the way to approvals. With our first approval, the company will become cash-flow positive. And we have enough cash in the bank to get us to multiple approvals, so that gives us additional diversification.”

The management team still on board after Hood’s departure is solid, united by decades-old friendship: Three of Kibar’s top executives also went to the elite Robert College high school. But he rejects any suggestion that he has simply surrounded himself with high school chums, saying instead that they have all reached such heights in their careers that the only reason a startup could have lured them is because of their confidence in him and his project.

The chief financial officer, Cevdet Samikoglu, cofounded a hedge fund, Greywolf Capital Management, after becoming a director and portfolio manager at Goldman Sachs following Harvard Business School. The chief legal officer, Arman Oruc, earned a master’s in economics from the University of Cambridge and a law degree at UC Berkeley before becoming a partner in Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, where he represented clients like MasterCard, Ericsson, LG and Novartis. And the chief medical officer, Yusuf Yazici, is an internationally known rheumatologist who has maintained his role as an assistant professor at NYU, where he is director of the Seligman Center for Advanced Therapeutics, which conducts all clinical trials in rheumatology for the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases.

They are on a journey together along a path that still holds suspense.

“These are all long-term projects, taking a molecule from discovery to animal studies to clinical and then commercialization. You’re talking a minimum 10 years,” Kibar says. “The data—we are sharing it with the FDA, and we shared it with the doctors. Beyond that, no matter what we share, people will either not understand or not care or not believe. So those are the skeptics. And in certain programs, they may turn out to be right. We haven’t done it yet.”

Photos by Casey Kelbaugh

It was lunchtime on a bright early autumn day in Madison Square Park, a peaceful, leafy rectangle in New York City. The park was busy with office workers, chatting, eating, or just enjoying the mild weather. I, however, was trying to avoid walking into a tree.

“The trick is to not watch your phone,” said Nick Johnson, a tall young man in a t-shirt that reminded the reader to “Hustle 24-7-365.” Johnson was indeed hustling: he had a long stride and only an hour to teach me how to play Pokémon GO.

“Look out for that fence,” he said.

Pokémon, you may recall, are fictional creatures that battle each other with the aid of their human “trainers.” The franchise was created in the late ’90s for the Nintendo Game Boy. It has since spawned dozens of iterations, from card games to plush toys to shrieking cartoons that you wish your kid had never found on Netflix.

The latest version is the wildly successful app, Pokémon GO. Since its launch in July of 2016, Pokémon GO has been downloaded more than half a billion times—and grossed more than $500 million dollars. For a little perspective, that’s over twice as much money as Ghostbusters II.

The latest version is the wildly successful app, Pokémon GO. Since its launch in July of 2016, Pokémon GO has been downloaded more than half a billion times—and grossed more than $500 million dollars. For a little perspective, that’s over twice as much money as Ghostbusters II.

The point of the game is fairly straightforward. You walk around “capturing” Pokémon. But when I downloaded the app, I had some trouble figuring it all out. First of all, I’m one of those unimaginative types who like to make their avatars resemble themselves. Unfortunately Pokémon GO offers no way to create a myopic bald man. (Are you listening, Nintendo?)

Once I got the game set up, I had problems figuring out how to play it. I was convinced that there was a Pokémon in my kitchen. After 20 or so minutes of fruitless searching, I realized that it was time to call in an expert.

It is no exaggeration to say that Nick Johnson is the most accomplished Pokémon GO player in the world. He was the first person to catch all 142 Pokémon in the United States. Then he was the first person to catch the three remaining Pokémon in Paris, Hong Kong and Sydney, Australia.

When we met in the park, Nick also turned out to be a pretty good teacher—or, Pokémon trainer trainer, if I may.

Like many games, Pokémon GO is simultaneously simple and complicated.

As Nick put it, the game is just a “fancy skin on Google Maps.” Meaning that when you’re hunting Pokémon with your phone, you’re searching for creatures superimposed upon the map. It’s not hard to get the hang of it once you grasp the proportions. For example, what I thought was my kitchen was actually my local coffee shop.

When you get close enough to a Pokémon, you swipe to hurl your Poké Ball—a parti-colored sphere—at the creature. And when the ball hits, the creature is yours.

In Madison Square Park, it took me a few tries to catch my first Pokémon, a cross-eyed, bucktoothed, purple vole named Rattata. It was waiting for me by the statue of William Henry Seward, Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state.

When the ball hit the Pokémon, my phone emitted a satisfying ping.

“There you go,” Nick said mildly. Meanwhile I experienced an absurdly outsized feeling of triumph. Perhaps not as triumphant as Seward felt when he blocked British recognition of the Confederacy, but triumphant nonetheless.

The more complicated parts of the game are the hovering “cube lures,” and hatching Pokémon, and raising up levels, and the possibility of having Pokémon battles with nearby players.

Nick explained all this stuff very patiently, and if most of it didn’t take, that’s more my fault than his. Nevertheless, I did glean some wisdom from the Ted Williams of Pokémon.

First of all, don’t use the camera.

“It makes it harder to catch them, and it kills your battery life.”

Second, as he’d already mentioned, “Keep your head up so you don’t die.”

Indeed, as we walked around Pokémon hunting, I almost walked into about 12 people. But Nick looked more at the real world than at his screen. Which is why he’s never had any Pokémon GO–related injuries. Unlike some other people.

“There was a Wall Street guy who was trying to get all the international Pokémon before I did. He broke his ankle in Sydney. He was hit by a car while trying to catch a Kangaskhan. After that he was like, screw this, and he went to Hawaii.”

Nick’s third rule: Walk in a straight line. There are rewards within the game for going certain distances, but the game measures distance as the crow flies: “So if you walk in a zigzag, it’s wasted energy.”

With Nick’s guidance, I caught a few more Pokémon. Then we grabbed a bench to discuss how a mild-mannered 20-something became the world’s greatest Pokémon GO player.

Did he consider himself a gamer?

“Gamer, nongamer—those categories don’t mean anything any more,” Nick said. “When you have 500 million people downloading an app, it just shows that in a way we’re all gamers. When I’m out playing, I meet everyone from little kids to retired people looking to get some exercise. My aunt is addicted to Candy Crush, but I wouldn’t call her a ‘gamer.’”

So if it wasn’t the gaming, how did he explain his obsession with Pokémon GO?

“There are two reasons I started. I watched the TV show when I was a kid, so there was that nostalgia aspect for me a little bit. The second reason was it’s kind of what I do for a living.”

Nick Johnson works as the head of platform for Applico, a tech advisory company. They help their clients build what’s called “platform” businesses. Many of today’s most successful companies—such as Google, Facebook and Uber—don’t make things; they own the platforms that connect people to one another.

In fact, along with Alex Moazed, an Applico colleague, Nick is the author of the recently published Modern Monopolies: What It Takes to Dominate the 21st Century Economy (St. Martins). The book explains how companies like Facebook gain an almost unassailable market share by “building and managing massive networks of users.”

So Nick wanted to understand the platform of Pokémon GO and how people interacted with it.

Then it became an obsession.

“I was playing the game every day after work,” Nick said. “I’d leave the office and go catch some Pokémon. Suddenly I realized I was close to catching them all. so I figured why not go for it.”

It took Nick two weeks, averaging eight miles of walking a day.

“Some nights I stayed up until 4 or 5 a.m. I’d go home, grab a little sleep, go to work, do it again. I mean, I was tired, but believe it or not, it was healthy. I lost weight. I started eating better, because you can’t be walking for hours on fried chicken. I learned a lot about New York City and I met people.”

“You met people?”

“I did. That’s the thing that a lot of people don’t realize—that there is a social aspect to the game. People are on Reddit exchanging tips and advice. One night I was at Grand Army Plaza in Central Park, and there must have been 300 people out catching Pokémon. Old people, young people, families, tourists. Justin Bieber was supposed to be around, but I didn’t see him.”

“Was that a disappointment?”

“No.”

After Nick caught the 142 Pokémon, he posted on Reddit about it.

“I answered some questions, went to sleep, and when I woke up, I had like 20 media requests.”

After appearing on shows like Good Morning America and in national newspapers like USA Today, Nick decided to take his Poké Ball around the world. In an admirable display of chutzpah, Nick got Expedia to spring for business class flights and Marriott Rewards to cover the lodging.

“I stayed in some sweet hotels,” he said.

In the span of four days, Nick caught the three remaining Pokémon in Paris, Hong Kong and Sydney, Australia.

Nick may be right about the pointlessness of categories like “gamer.” You’d expect someone with this level of devotion to be intensely single-minded. But he has other pursuits: He’s into soccer, or at least the European kind.

“American soccer is like Google+,” he said. “The only people interested are those involved with it.”

And with Nick there is a thoughtfulness alongside his intensity. Wind, Sand and Stars, the lyrical aviation memoir of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, is his favorite book. He reads serious fiction by J.F. Powers, David Foster Wallace and William Gaddis.

While all these details demonstrate that Nick is a well-rounded guy, they don’t quite explain what drove him toward this kind of digital achievement. When I pressed him on this, he pointed to his T-shirt—“Hustle 24-7-365”—and smiled.

“If I do anything, I do it 100 percent,” he said. “I take everything to its logical extent.”

Nick had to get back to his desk. He had work to do. We shook hands, and the Pokémon GO master of the world headed for his office, his phone firmly in his pocket.

But I already had my phone out. I quickly canceled my next appointment. Then I stayed in the park to catch some Pokémon.

A long, long time ago—way back when Facebook was young—Virginia and I discussed the possibility of becoming “friends” in that newfangled way.

A long, long time ago—way back when Facebook was young—Virginia and I discussed the possibility of becoming “friends” in that newfangled way.

I was ambivalent about this new style of virtual, public, quote-unquote friendship, but I thought she might be eager for the novelty, given that she was the most curious, modern 90-something person who ever lived.

I mean, Virginia’s entire life—for nearly 10 decades—was a testament to the power of humans to evolve.

Think about it: Here’s a girl born, in Oklahoma, before American women have the right to vote. In the 1930s, she lives in Germany, where she joins a dance troupe. After World War II, she lives in Chicago, where she writes radio soap operas. She becomes a professor of French at Pomona College, then a high-ranking college administrator. She raises two kids.

And that’s just the beginning.

After her husband dies, in her so-called retirement, she moves to Paris, alone. She writes novels. She is an early adopter of the Kindle and, when it became trendy in Paris, of boxed wine. She takes Pilates classes before most Americans have ever heard of Pilates.

Thoroughly modern Virginie. Wouldn’t she want to join Facebook?

Non, non et absolument pas.

“I am still unbending in regard to Facebook,” she replied in an email. “Darn it, for me friendship is private and personal—as with lovers, not that that question is an issue at the moment.”

Friendship—the private and personal kind—was Virginia’s gift to me, to many of us in this room, one of the greatest gifts of my lifetime.

When I met her, in 1971, I would never have dreamed that one day I’d call her my friend. Or call her Virginia.

She was Madame Crosby, my middle-age French professor—regal, demanding, with a demeanor as efficient as her matronly bun. In her presence, I always felt I was slouching.

I struggled to make it on time to her 8 a.m. French 51 class. The only things I could say with confidence were “Pardon” and “Répétez, s’il vous plaît.”

Non, pardon, Madame, I have not read that excerpt from “Huis Clos.”

I gave Madame Crosby no reason to think I was a student worth her time, but in my junior year, I signed up for a semester in France. She was my advisor.

As part of my semester abroad schoolwork, I had to keep a journal, in French. It was a black book with unlined pages in which I recorded exciting moments like, “Je suis allée au musée.”

Then the semester ended. Rather than take my prepaid flight home, I decided to stay in France for the summer. But there was a problem.

I had no money. No. Money. And so began a series of adventures that included taking a job on a yacht as a cook for three Frenchmen who, as it turned out, had a very loose translation of “cook.”

Through that summer, I was broke, scared, confused, hungry, elated—and I wrote it all down in my little black journal, which, at the beginning of the new school year, I dutifully brought to Madame Crosby.

I warned her that some of it was very personal, that she might not want to read it all.

A few days later, she summoned me to her office. I don’t remember exactly what she said, but she had read it all. In her crisp way, she let me know she wanted to make sure I was OK.

It was a breakthrough moment in my life. For the first time, a professor at Pomona College made me feel noticed and cared for, and that was the beginning of my friendship with Virginia, the beginning of our long conversation.

As you all know, Virginia gave great conversation. It ranged from just the right amount of tart gossip to books (she loved haute literature and trashy mysteries) to politics (Go Democrats) to the meaning of life.

Once, as I was thinking about all the discoveries and inventions she’d lived through—from the electric refrigerator to the Internet—I asked her what she thought the next great frontier would be.

“The brain,” she promptly said. Until we understand the brain, she believed, we won’t understand anything.

As the years wore on, we talked a lot about aging. She didn’t like it. But she faced it with her bracing humor and candor.

One day while I was in her Paris apartment, a young workman was fixing something in the garden out back. He was sweating, no shirt. She watched him. She sighed. Oh, she said, how she missed the days when she didn’t feel invisible to young men.

Virginia maintained close relationships with a number of former students. They adored her; she thrived on them. My brother Chris, who lived near her in Paris, became one of her dearest friends.

I did have to point out to her, however, that in at least one of her novels, the students were vile, conniving creatures. As I recall, she killed off at least one.

Purely a plot device, she assured me.

My classmate, Talitha Arnold, captures part of what endeared Virginia to her students like this: “What she offered us was so much more than French. But through French, she opened a whole world of culture, history and travel that I’d only had a glimpse of as a public school kid from a junior high teacher’s family in Arizona.”

Virginia also gave us a vision of how a woman might live a forceful, independent, fruitful life well into old age. For women my age, she was a role model before we knew the words “role model.”

Yet Virginia fretted that she had led a selfish life. She said that to me more than once. She worried that she hadn’t done much for others, hadn’t sacrificed sufficiently. I assured her that she had done something life-changing for many of us:

She gave us her friendship.

Through her friendship—personal, private friendship—she helped us see more clearly. She inspired, excited, encouraged us, laughed heartily at our jokes. She made us feel valued, seen. She made us more real to ourselves.

Virginia loved attention—“I’m a performer” she once said when I asked her the key to her resilience—but unlike many people who love attention, she also gave it, whole-heartedly. She was curious to the point of hungry. How are you? How’s your family? Are you happy?

She often asked me that—are you happy?—and then we’d have a long discussion on the nature of happiness.

This spring, I was among the many people who paraded to her bedside to say thank you and goodbye. I asked her how she felt about all the well-wishers.

“It’s fine,” she whispered, “as long as they can express sentiment without being sentimental.”

To her, sentimentality seemed like a form of sloppiness, but the truth is, she could be very generous in expressing her feelings—her love, her encouragement—though often with an apology attached: “I fear I’m becoming sentimental in my old age.”

Good, Virginia, good. Go for it.

A final thought.

One day this April, when she was mostly confined to bed, she said something in French as I walked out the door.

Damn, I thought. My French still sucks. I have no idea what she said.

I leaned over her bed. Répétez, s’il vous plaît?

She hoisted an imaginary wine glass and in a raspy voice said, “Vogue la galère!”

Those were the words, she said, that she wanted to “go out” on.

When I got home, I looked it up. It has various definitions. Here’s the one from Merriam-Webster:

Vogue la galere: Let the galley be kept rowing; keep on, whatever may happen.

For almost 100 years, that was Virginia, keeping on whatever happened, encouraging the people who loved her to do the same.

Vogue la galère, ma chère amie.

This is the text of a eulogy delivered by Mary Schmich ’75 at a memorial service for Professor Emerita of French Virginia Crosby. Schmich is a columnist for the Chicago Tribune.

Alumni Weekend 2016

Here are a few photos from the 2016 Alumni Weekend, held in April. For information about the event, see the Alumni Bulletin Board.

—Photos by Carlos Puma

Sagehens Celebrate 4/7 with Good Deeds

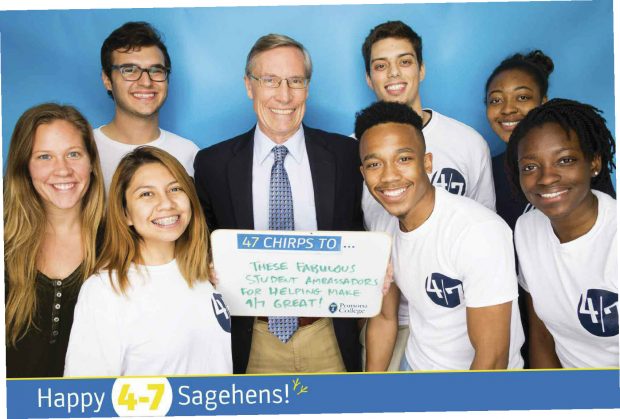

President David Oxtoby poses with a group of student volunteers on 4/7 Day, 2016

On April 7, Pomona hosted the second annual Celebration of Sagehen Impact to honor and recognize the good work and good will of our community of “everyday Daring Minds.” Sagehens around the world flooded the Pomona Alumni Facebook group with thousands of likes, comments and posts about alumni service projects, while more than 500 students braved spring rain on campus to celebrate this special day of community spirit. 47 chirps to Sagehens near and far for bearing your added riches, and for another year of uplifting community support that is solidifying the 4/7 Celebration of Sagehen Impact as a proud, new Pomona tradition! To see a sampling of posts from alumni participants, visit facebook.com/groups/sagehens and search for #SagehenImpact.

Pomona Book Club

In April, Pomona’s new Alumni Learning & Career Programs team launched the Pomona College Book Club on Goodreads. The Book Club connects Pomona alumni, professors, students, parents and staff around a common love of reading. Become a member by visiting pomona.edu/bookclub to check out a summer reading list of recommendations from some of this year’s Wig Award–winning faculty and share your own favorite books.

Alumni Weekend and Alumni Award Winners

Julian Nava ’51 (center) with professors Tomás Summers Sandoval Jr. and Miguel Tinker Salas

Gretchen Berland ’86

John Edwards ’64

Pat Riggs ’71

Ed Krupp ’66

Alumni Weekend, April 28 through May 1, 2016, brought nearly 1,600 Sagehens home to Claremont for a weekend of fun and reconnection. In addition to cornerstone activities such as class dinners, guest speakers, the alumni vintner wine tasting and the parade of classes, guests of Alumni Weekend 2016 enjoyed tours of the new Studio Art Hall and Millikan Laboratory, tasted local craft beers with the Class of 2016, attended a Presidential Search Forum and engaged in discussion with executive staff in a town hall–style forum regarding current campus issues. Looking forward to your reunion year or just pining for some California sunshine among hundreds of Sagehen friends? Be sure to mark your calendars for the last weekend of April and return to campus for Alumni Weekend 2017!

Alumni Weekend 2016 was also an occasion for guests to hear from 2016 Blaisdell Distinguished Alumni Award winners Gretchen Berland ’86, Ed Krupp ’66, Julian Nava ’51 and to honor Blaisdell winner George C. Wolfe ’76, who could not attend the celebration. Alumni Distinguished Service Awards were presented to John Edwards ’64 and Pat Riggs ’71. Learn more about these annual awards and their deserving recipients at pomona.edu/alumni/services-info/awards.

(For more photos, see Last Look on page 64.)

Thanks to Onetta

47 hearty chirps to Onetta Brooks ’74 for a year of thoughtful leadership and dedicated service as Pomona’s 2015–16 President of the Alumni Association! Onetta proved a wonderful steward for the board’s evolution to a more action-oriented group, and exhibited her commitment to a thriving alumni community throughout the year during alumni events and 4/7 activities, organization of responses to the Title IX policy and engagement in conversations about

47 hearty chirps to Onetta Brooks ’74 for a year of thoughtful leadership and dedicated service as Pomona’s 2015–16 President of the Alumni Association! Onetta proved a wonderful steward for the board’s evolution to a more action-oriented group, and exhibited her commitment to a thriving alumni community throughout the year during alumni events and 4/7 activities, organization of responses to the Title IX policy and engagement in conversations about

inclusivity. Many thanks, Onetta!

Travel-Study

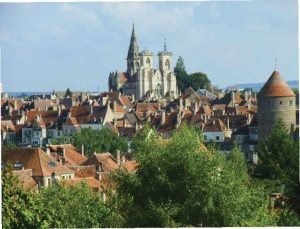

Burgundy: The Cradle of the Crusades

May 29–June 10, 2017

May 29–June 10, 2017

Join John Sutton Miner Professor of History and Professor of Classics Ken Wolf on a walking tour of Burgundy. Burgundy, the east-central region of France so well-known for its food and wine, was also an incubator for two of the most distinctive features of the European Middle Ages: monasticism and crusade. This trip provides the perfect context for exploring “holy violence” in the Middle Ages and its implications for the 21st century.

Each spring, juniors and seniors recognize outstanding Pomona professors by selecting the recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on faculty. This year’s recipients are (left to right in the image above):

Each spring, juniors and seniors recognize outstanding Pomona professors by selecting the recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on faculty. This year’s recipients are (left to right in the image above):

Pierre Englebert, H. Russell Smith Professor of International Relations and professor of politics, teaches courses like Advanced Questions in African Politics, Comparative Politics of Africa, and Political Economy of Development. He has been at Pomona since 1998, and this is his fourth Wig Award.

Sharon Goto, professor of psychology and Asian American studies, teaches courses including Asian American Psychology, Industrial/Organizational Psychology, and Psych Approaches: Study of People. She has been at Pomona since 1995, and this is her second Wig Award.

April Mayes ’94, associate professor of history, teaches courses on Afro-Latin American History, Gender & Nation: Modern Latin America, and U.S.-Latin American Relations, among others. She is a graduate of Pomona, and has taught here since 2006. This is her first Wig Award.

Kyla Tompkins, associate professor of English and gender & women’s studies, teaches 19th-Century U.S. Women Writers, Literatures of U.S. Imperialism and Advanced Feminist and Queer Theory, among other classes. She has been at Pomona College since 2004, and this is her first Wig Award.

Jonathan Hall, assistant professor of media studies, teaches courses that include Freud, Film, Fantasy; Japanese Film: Canon to Fringe; and Queer Visions/Queer Theory. He has been at Pomona since 2009, and this is his first Wig Award.

Johanna Hardin ’95, professor of mathematics, teaches courses that include Linear Models, Computational Statistics, and 9 out of 10 Seniors Recommend This Freshman Seminar: Statistics in the Real World. A graduate of Pomona, she has taught at Pomona since 2002. This is her first Wig Award.

Michelle Zemel, assistant professor of economics, teaches courses that include Economic Statistics, Advanced Topics in Banking, and Risk Management in Financial Institutions. She has been at Pomona since 2012, and this is her first Wig Award.

Nicole Weekes, professor of neuroscience, teaches The Human Brain: From Cells to Behavior (with Lab), Neuropsychology (with Lab), and Introduction to Psychological Science. She has been at Pomona since 1998, and this is her fourth Wig Award.