Sometime this fall, the Pomona College Museum of Art will cease to exist, and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College will be born in its beautiful new quarters on the opposite corner of the intersection of College and Second. To prepare for that change, for the past few months, the museum’s associate director and registrar, Steve Comba, has been overseeing the effort to inventory, pack and safely move approximately 15,000 valuable and often fragile art objects from the museum’s old storage into the new. Already in their new home are the artifacts of the museum’s Native American collection, previously stored in the basement of Bridges Auditorium and brought out mainly for visiting schoolchildren.

Sometime this fall, the Pomona College Museum of Art will cease to exist, and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College will be born in its beautiful new quarters on the opposite corner of the intersection of College and Second. To prepare for that change, for the past few months, the museum’s associate director and registrar, Steve Comba, has been overseeing the effort to inventory, pack and safely move approximately 15,000 valuable and often fragile art objects from the museum’s old storage into the new. Already in their new home are the artifacts of the museum’s Native American collection, previously stored in the basement of Bridges Auditorium and brought out mainly for visiting schoolchildren.

Articles Written By: Staff

Art on the Move

100 Years Ago

It’s 1920, and Pomona College is entering the Roaring Twenties—facing, among other things, the challenges of dancing and Hollywood.

Everybody Dance

With the close of World War I came a push to overturn the strict college rules against dancing on campus. As recently as 1918, an editorial in The Student Life had lamented that “The principle of non-dancing has become ingrained into the very fiber of the institution for reasons which the executives can best express, and it is worse than futile for us to oppose it.” The post-war culture shift, however, soon carried away that prohibition, and, as informal campus dances became common, the efforts of the administration turned to managing them. A floor committee of four men and four women supervisors were authorized “to reprimand any undesirable form of dancing or to request any person to leave the floor.” By 1922–23, four all-college formal dances were being conducted annually in the “Big Gym”—the Senior-Freshman Dance, the Christian Dance, the Military Ball and the Junior Prom.

Silence is Golden

As Hollywood became the movie capital of the world, the Pomona campus soon came into demand as a collegiate set. The Charm School, a silent feature starring Wallace Reid, was the first known movie to be shot on campus, with much of it filmed around Pomona’s Sumner Hall in 1920.

1,000 Strong

The 1921 Metate (published in 1920) notes that for the first time the number of Pomona alumni has topped 1,000.

For more tidbits of Pomona history, go to Pomona College Timeline.

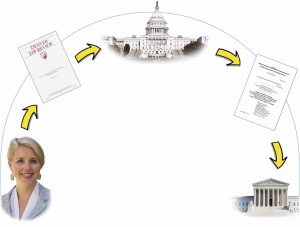

Papers, Politics, Policy

How Prof. Amanda Hollis-Brusky’s paper on the promotion of a theory of executive power and its consequences is making its way to the other two branches of government

In 2011, during her first year at Pomona College, Politics Professor Amanda Hollis-Brusky wrote a paper on the rise of the “unitary executive theory,” used in recent decades to promote the notion of the primacy of presidential power and limit the autonomy of federal agencies. The paper was part of Hollis-Brusky’s larger work on the conservative legal movement.

In January, U.S. Senators Sheldon Whitehouse, Richard Blumenthal and Mazie Hirono cited and relied heavily on Professor Hollis-Brusky’s in their amicus curiae brief filed in a big U.S. Supreme Court case Seila Law v. CFPB, which may decide the fate of the Obama-era Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Arguments are set for March 3.

In Brief

Marshall Scholar

Isaac Cui ’20 has won a prestigious Marshall Scholarship to fund his graduate studies in the United Kingdom next year. During his two years in the U.K., Cui hopes to study at the London School of Economics as well as study political science at the University of Manchester.

Churchill Scholar

Elise Koskelo ’20 has been named one of only 16 American students to win this year’s Winston Churchill Foundation Scholarship to study and conduct research at the University of Cambridge. She plans to study quantum magnetism and superconductivity.

Sustainable Thesis

The senior thesis of Sara Sherburne ’19, titled “Let’s Get Sorted: The Path to Zero Waste,” was recognized last fall by the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education as one of six winners of the national Campus Sustainability Research Award.

Solar Cell Grant

Pomona and Harvey Mudd were recently awarded a National Science Foundation Major Research Instrumentation Grant of $442,960 for new lab equipment to support research and development of next generation solar cells.

Paralympic App

While attending the 2015 Paralympic National Games in his home country of India, Arhan Bagati ’21 saw athletes literally crawling up stairs. So he created an app to guide Paralympians to locations that are accessible, including bathrooms, restaurants, theatres and more. The result was InRio and its successor, the IndTokyo app for the 2020 Tokyo Paralympic Games, available on iTunes and Google Play.

Post/Truth

The theme of the Humanities Studio’s 2019–20 speaker series is “post/truth,” exploring the various facets of today’s post-truth (un)reality through a series of speakers and seminars, including a “Fake News” Colloquium.

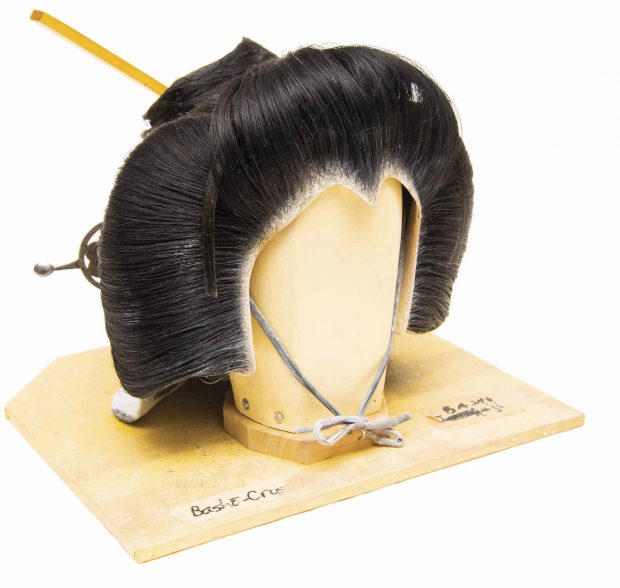

Pomona’s Kabuki Heritage

In the early 1960s, the late Professor Leonard Pronko discovered the Japanese art of kabuki while studying theatre in Asia on a Guggenheim Fellowship. He then made history in 1970 as the first non-Japanese person ever accepted to study kabuki at the National Theatre of Japan. Bringing his fascination back to Pomona College, he directed more than 40 kabuki-related productions over the years, ranging from classic plays to original creations. The wig pictured here is one of several that remain from those productions. Below are a few facts about that intriguing Pomona artifact. (For more about Professor Pronko’s life, see In Memoriam.)

In the early 1960s, the late Professor Leonard Pronko discovered the Japanese art of kabuki while studying theatre in Asia on a Guggenheim Fellowship. He then made history in 1970 as the first non-Japanese person ever accepted to study kabuki at the National Theatre of Japan. Bringing his fascination back to Pomona College, he directed more than 40 kabuki-related productions over the years, ranging from classic plays to original creations. The wig pictured here is one of several that remain from those productions. Below are a few facts about that intriguing Pomona artifact. (For more about Professor Pronko’s life, see In Memoriam.)

Fact 1: One of about 20 wigs kept by Pomona’s Department of Theatre and Dance in its restricted costume storage area, this geisha-style wig is part of a collection of props and costumes obtained by Pronko from Japan for his classic kabuki and kabuki-inspired theatre productions.

Fact 2: Like all wigs for female characters, it was intended to be worn by an onnagata, a male kabuki actor who performed in women’s roles.

Fact 3: Other kabuki-related items in theatre storage include swords, wigs, costumes and costume accessories.

Fact 4: Today, the costume storage area holds more than 200 period garments and 300 pieces of jewelry.

Fact 5: Most such wigs are made of either human or horse hair and styled with lacquer.

Fact 6: The origins of the Japanese word “kabuki” are simple and elegant: “Ka” means song; “bu” means dance; and “ki” means skill.

Fact 7: Pronko wrote extensively about the art of kabuki, which he said attracted him because it was so “wildly theatrical.”

Fact 8: Pronko also taught the stylized movement and vocal techniques of kabuki to generations of Pomona College students.

Fact 9: He directed a number of classic kabuki plays, including Narukami Thundergod, Ibaraki and Gohiki Kanjincho.

Fact 10: He also staged kabuki versions of such Western classics as Macbeth.

Fact 11: One of his most original productions was a “kabuki western” titled Revenge at Spider Mountain, based on his love of Native American folklore and inspired by two classic plays: Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees and The Monster Spider.

The Poetry of Grief

Grief Sequence

By Prageeta Sharma

Wave Books

104 pages

Paperback $20

PROFESSOR PRAGEETA SHARMA’S recently released collection of poems, Grief Sequence, has garnered acclaim from corners with cachet. In this, her fifth book, Sharma chronicles the loss of her husband to cancer and, as The New York Times put it, she “complicates her narrative away from sentimentality and into reality-fracturing emotionality.” PCM’s Sneha Abraham sat down with Sharma to talk about death, life and the poetry she made in the midst of it all. This interview has been edited and condensed for space and clarity.

PCM: What was the inspiration? It’s loss but can you explain a little bit about it?

Sharma: This one is very different from my other books. My last book had a lot to do with race and thinking through the ideas of belonging and institutions and race and community and who gets to be a part of a community and who is outside of that community by the nature of racial differences and gender. But this one just happened because in 2014 my late husband Dale was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and he died two months after diagnosis.

And so, I was in shock and I had no sense of what had happened and, often they say with shock you lose your memory. So, for several months I couldn’t remember our long marriage. I could only remember those two months of his progressing sickness. When I told my father, who’s a mathematician who specializes in math education, that I was having trouble with sequencing (because it was something I was starting to notice), he said, “Oh well, you’ve always had trouble with sequencing. I tested you when you were five or six.” So it was sort of this joke we had about the concept of sequencing. It led me to research theories of sequential thinking; I started to think about the process of sequencing events and what to do for your recall, and what you do to process trauma, deep feelings and difficulty; I started to write in a prose poem format as much as I could: to place on a page what I could recall. And I was also doing that because I felt truly abandoned by Dale’s illness and death, which were very sudden. He died of a secondary tumor that they discovered after he inexplicably lost consciousness. So, I never had any closure. I didn’t get to say goodbye. We thought we had several months left and didn’t prepare for his death. We had no plans of action.

He was such a complicated person that, to not have had any last conversations just put me into a state of despair. It was an unsettling place, so I had to write myself through it and speak to him and document the days through my poems. And what I didn’t realize was that with such grief comes a fierce sense of loving—believing in the concept of love. Many people say this especially when they lose a spouse—they lost someone they loved, and they didn’t plan on losing them, so they’re still open to the world and to love. They’re still open to feeling feelings. So I started to learn more about my own resilience and my strength, and I was really receptive to the process of becoming my own person. It was painful, but I wanted to document the fact that I knew that when I was at a better place of healing I would feel very differently, and the poems might look different, which they did.

PCM: People talk about the stages of grief. Did you find yourself going through that as you wrote the poems?

Sharma: The joke is that you’re always going through different stages so they’re never linear.

PCM: No, no. They’re not linear.

Sharma: So, I think I went through them all in a jumbled way. I think they hold you in them. Dale was a really complicated person, so I had to really think about who he was, who he is. I learned you love two people at once — you stay in the living world but you still love the person you lost. Grief Sequence has many kinds of love poems. Towards the end of the book are love poems to my current partner Mike, a widower, who helped me through the grieving process.

PCM: You both have that understanding, what that’s like.

Sharma: Yeah. The poems are about grief, love, and they’re about really trying to learn to trust the journey. These poems have taught me so much about my emotions, sequencing and my community.

PCM: Is there a particular poem in “Grief Sequence” that really gets to you or pierces through all of it for you? Is there a pivotal poem in there?

Sharma: I think that there are a variety of poems here. Some poems are processing Dale getting sick. Some are processing experiences with others that are sort of surprising—people can alienate you when they witness you in deep grieving, because some gestures or reactions aren’t pleasant. I began processing what gets in the way of your grief. We can sometimes get hijacked by other people’s treatment, and you forget that you’re really spending this time trying to just protect your feelings. Speaking to widows really helped me. Reading all the books I could find helped; my biggest joke is that the book that helped me the most, which—I mean, it’s sort of embarrassing, but it’s hilarious—is Dr. Joyce Brothers’ Widowed.

PCM: No shame.

Sharma: It was so practical: You have to learn how to shovel the driveway, relearn the basics. It was all of these lists. These basics are the ones that people don’t talk about: the shared labor you have with your partner and what you then have to figure out after their death. For example, my cat brought in mice, and I didn’t realize how often Dale would handle that. Things like that. So, the book was so practical that I just remember reading it cover to cover. I laughed so much when I recognized myself in there.

PCM: Those day-to-day gaps that you don’t realize you’re missing.

Sharma: Make sure to eat breakfast. Try to get enough sleep. So many basics.

PCM: When you’re in grief, I’m sure all those … you need it.

Sharma: All those things, yeah.

PCM: What did you find people’s responses are to the poems? Did you find that people expected you’ve gotten over it now that you’ve written this book?

Sharma: It may be the book; it may be also including a new relationship in the book. I never understood how somebody could move forward, but you really understand it when you have no choice. I think the book helped me document the experiences in real time. Readers have been very generous. I think they didn’t expect the book to be so explicit. One thing that I was also trying to negotiate in the book was poetic forms. Because I’ve taught creative writing for a long time and we teach form, and particularly the elegy, I was reacting to the beauty of the elegiac poem; it can be so crafted that often you’re not feeling like it’s an honest form to hold tragic grief. You can write a beautiful elegy in a certain way, but the tragic losses some of us can experience—or lots of us—may not produce a beautiful poem, and that beauty can be something that almost feels false to access. And so, I started to question the role of how the poem works or what people expect to read as an elegy.

PCM: Talk about some of your early influences in terms of poetry.

Sharma: I think I started writing poetry in high school like lots of people, and so I was really fascinated with what contemporary poetry looked like, reading it from The Norton Anthology of Poetry. And I think about it now and I was often interested in women writers of color, though they were very few. And then I think some women who were writing “poetry of witness” and kind of trying to figure out what their narratives in the poems were about.

PCM: Can you explain “poetry of witness”?

Sharma: According to many poets, it is poetry that feels it is morally and ethically obligated to bear witness to events and injustices like war, genocide, racism and tyranny. Many poets I read during my high school years who wrote about these events bore witness to it in other countries and often about cultures outside of their own. It led me to wonder and examine the distance between their testimony and the culture itself. It also forged the desire in me to read more internationally and in translation rather than through this particular style and method of writing.

PCM: When did it crystallize for you that you wanted to be a poet?

Sharma: I felt like it was a calling back in college but I think it was really applying to graduate school right from undergraduate and getting into a top creative writing program (also getting a fully funded scholarship). I was 21 years old and I just thought, well, this must mean something. And then when I got to grad school, I found a community of poets and that felt right to me. I am so grateful to those people—many are still very close friends today.

Bulletin Board

Mark Your Calendar

It’s time to mark your calendars for a return to campus on Alumni Weekend 2020, which will take place April 30 to May 3. For more information, go to the Reunion & Alumni Weekend website.

It’s time to mark your calendars for a return to campus on Alumni Weekend 2020, which will take place April 30 to May 3. For more information, go to the Reunion & Alumni Weekend website.

2020 Winter Break Parties

This past January, Pomona’s annual Winter Break Parties welcomed over 400 Sagehen alumni, students, families and friends at events in New York City, San Francisco, Washington D.C., Seattle, Portland, Los Angeles and Orange County, Calif. Attendees enjoyed time to reconnect, meet new members of the Pomona community and learn about news from campus. Thank you to everyone who attended and to our hosts Elizabeth Bailey and David Bither P’21, Donna Yoshida Castro ’83 P’21, Jim McCallum ’70, Kathryn & Charles Wickham P’20, Tricia and Steve Sipowicz P’22, Meg Lodise ’85 and Diane Ung ’85 and the Orange County Alumni Chapter, all of whom helped make each event memorable for everyone!

Pomona Now and Next Campaign Raises Nearly $400,000 For Scholarships

Alumni at a Winter Break party in Newport Beach, Calif.

Alumni at a Winter Break party in New York City.

Alumni at a Winter Break party in Los Angeles.

Running in tandem with the Ideas@Pomona Summit, the Pomona Now and Next crowdfunding campaign set out to support the Pomona liberal arts experience and scholarships and to meet a goal of 1,000 donors with $250,000 in bonus gifts unlocked by the end of the Summit. Thanks to the generosity of several Pomona College Trustees who contributed to create the unlocking gifts and the 1,200+ donors who exceeded the goal and gave almost $150,000 by the campaign’s close, Sagehens collectively raised nearly $400,000!

Our most successful crowdfunding campaign to date, Pomona Now and Next received gifts from over a third of the Summit attendees who excitedly watched the progress bar increase during the event and counted alumni, parents and more than 100 students among its donors.

Thank you to everyone for the incredible generosity shown in support of Pomona students. Chirp! Chirp!

Join the All-New Sagehen Connect

Announcing the launch of the all-new Sagehen Connect alumni community! New features include desktop and mobile versions, updated privacy settings and Sage Coaching for career interests and graduate school. For those who still have the previous Sagehen Connect mobile app, please be sure to remove it from your device as it is no longer functional.

With the new Sagehen Connect, alumni can:

- Access Pomona’s full, official alumni directory with multiple search options.

- Choose what profile information you want to display and share with fellow Sagehens.

- Log in with email, LinkedIn, Google or Facebook.

- Easily integrate your LinkedIn information with your profile.

- Register as a Sage Coach to help alumni or students with career and graduate school advising, job and internship search, resume review, career panels and presentations and more. You choose your level of involvement.

- See who has already registered on the site and invite your Pomona friends to join Sagehen Connect directly from the site, using email or social media.

- Opt-out at any time.

Visit Sagehen Connect to learn more and set up your login today.

Call for Alumni Association Board Nominations

The Pomona College Alumni Association Board consists of highly-engaged alumni who foster connection, action and impact among the 25,000-person strong alumni community. Members serve three-year terms and are selected based on self-nominations and recommendations from active alumni. The Board represents a diverse range of backgrounds, experiences and professions and spans every decade from the 1960s through the 2010s.

Nominate yourself or another alumnus/a for the Alumni Association Board online.

How to Become Dean of Pomona College

Growing up in Alabama, the son of two history scholars, develop an abiding interest in ancient civilizations. Fall in love with things even older at age 5 when your mom brings you a fossil trilobite half a billion years old from a vacation in Utah.

Growing up in Alabama, the son of two history scholars, develop an abiding interest in ancient civilizations. Fall in love with things even older at age 5 when your mom brings you a fossil trilobite half a billion years old from a vacation in Utah.

Discover in grade school that you can find fossils of sea creatures 80 million years old right behind your school. Carry that fascination with the geological record through high school to the College of William and Mary.

Discover in grade school that you can find fossils of sea creatures 80 million years old right behind your school. Carry that fascination with the geological record through high school to the College of William and Mary.

In college, go on a road trip organized by a faculty mentor to the Grand Canyon and the White Mountains of California, including an unexpected detour to Utah where you encounter the source of your very first trilobite, the House Range.

In college, go on a road trip organized by a faculty mentor to the Grand Canyon and the White Mountains of California, including an unexpected detour to Utah where you encounter the source of your very first trilobite, the House Range.

Go to the University of Cincinnati for your master’s in geology. Take a course with your future Ph.D. advisor, then on sabbatical from UC Riverside, and find her interest in studying ancient ecosystems through their fossils contagious.

Go to the University of Cincinnati for your master’s in geology. Take a course with your future Ph.D. advisor, then on sabbatical from UC Riverside, and find her interest in studying ancient ecosystems through their fossils contagious.

Following your mentor to California for doctoral studies, take your fascination with that first trilobite full circle when you decide to focus your Ph.D. thesis on the Cambrian ecosystems recorded in Utah’s House Range.

Following your mentor to California for doctoral studies, take your fascination with that first trilobite full circle when you decide to focus your Ph.D. thesis on the Cambrian ecosystems recorded in Utah’s House Range.

As a teaching assistant at UC Riverside, find that you love teaching and get your first administrative experience when you’re hired as director of a program to train new science teaching assistants.

As a teaching assistant at UC Riverside, find that you love teaching and get your first administrative experience when you’re hired as director of a program to train new science teaching assistants.

Get hired for a one-year position as visiting assistant professor of geology at Pomona and fall in love with the place and its students. Apply for a tenure track position, and to your surprise, get your dream job.

Get hired for a one-year position as visiting assistant professor of geology at Pomona and fall in love with the place and its students. Apply for a tenure track position, and to your surprise, get your dream job.

As an expert on the ecosystems and geology of the Cambrian explosion of life forms, travel the world and take part in some of the biggest paleontological discoveries of our time, from Canada to China.

As an expert on the ecosystems and geology of the Cambrian explosion of life forms, travel the world and take part in some of the biggest paleontological discoveries of our time, from Canada to China.

Serve as chair of the Geology Department and take leadership roles in college governance. Among other things, help create the position of chair of the faculty and co-chair the Strategic Planning Steering Committee.

Serve as chair of the Geology Department and take leadership roles in college governance. Among other things, help create the position of chair of the faculty and co-chair the Strategic Planning Steering Committee.

Though you’re shocked to be asked, agree to lead the College’s academic program as interim dean for one year; then, persuaded by the pleasure of working with the faculty, agree to serve for three years.

Though you’re shocked to be asked, agree to lead the College’s academic program as interim dean for one year; then, persuaded by the pleasure of working with the faculty, agree to serve for three years.

A Journey of Faith and Inquiry

Paul Kiefer ’20 outside the Shabazz Restaurant in Durham, N.C., adjacent to the state’s oldest mosque.

PAUL KIEFER’S JOURNEY of faith and inquiry already has taken him great distances. An American Muslim from Seattle who converted as a teenager, Kiefer ’20 studied abroad in Morocco during his junior year to experience the Arabic-speaking Muslim world. Back home in the United States, he looked toward the American South as he prepared to write his senior thesis in history.

There, he was an outsider of a different sort, a white Muslim gathering oral histories and conducting research on the Southern Black Muslim community that emerged in North Carolina in the 1950s and has grown deep roots in the Tar Heel State—a place where the festival of Eid is sometimes celebrated with fried fish and grits.

“They’re doing it right, the whole Southern thing,” says Kiefer, who was partly drawn to the region because of his family’s history there, though his relatives were not Muslim.

The Black Muslim community in North Carolina that was first planted by the Nation of Islam and later gravitated toward the teachings of W. Deen Muhammad is the subject of Kiefer’s thesis, “A Crescent Moon Rises in Dixie: The Foundation and Development of a Southern Black Muslim Community, 1955-1985.”

“Paul is writing about a topic few historians have investigated. So his work is filling a gap in our collective understanding of the Nation of Islam in the South,” says Tomás Summers Sandoval, associate professor of history and Chicana/o-Latina/o studies. “The archival work he’s done so far is already helping to write that history.”

Kiefer’s research weaves source material such as mosque records and contemporary newspaper reports with oral history interviews he conducted in North Carolina during a Summer Undergraduate Research Program project before his senior year.

“We often think of Islam in the U.S. as a present-day story but Paul’s work is a reminder of the importance of both Islam and Muslims to the U.S. past,” Summers Sandoval says. “At the same time, his work helps us better understand the roles various congregations and faiths played in the mid-century quest for Black liberation and autonomy in the South.”

Islam was not truly new to the South when it was imported from Northern cities such as Philadelphia and Baltimore in the second half of the 20th century. Kiefer found records of Black mosques in the South as early as 1928 and a Black Muslim farm by 1943, though those groups were members of the Moorish Science Temple of America, not the Nation of Islam.

Even less widely known: Islam’s original roots in the South preceded the Civil War.

“About 15 to 20 percent of enslaved people in what became the United States were Muslims,” Kiefer says. “There are many well-documented examples of Muslims who practiced openly, who ran Friday prayers on plantations, who wrote letters home. At least three actually wound up going back to West Africa thanks to letters they wrote home in Arabic.”

The history of Muslims in the South is a story worth telling, and Kiefer plans to tell many more. He has applied for a Fulbright-National Geographic Storytelling Fellowship and the NPR Kroc Fellowship, both designed to develop journalists as well as storytellers in other mediums. While awaiting fellowship announcements in the spring, Kiefer also plans to apply for public radio jobs, pursuing his determination to uncover little-known stories and histories.

Talking While Black

SIMPLE TRAFFIC STOPS escalate, ending in unnecessary deaths. In courtrooms, justice is not always served. And in prisons, the voices of many of the incarcerated sound alike.

SIMPLE TRAFFIC STOPS escalate, ending in unnecessary deaths. In courtrooms, justice is not always served. And in prisons, the voices of many of the incarcerated sound alike.

As a sociolinguist, Assistant Professor of Linguistics Nicole Holliday specializes in the study of how language and identity interact. More specifically, she focuses on the many implications of a central question: What does it mean to sound Black?

Holliday’s research on race and intonational variation examines wide aspects of society, including political speech. Yet there are few areas where the impact of race and linguistic differences is more stark than in the criminal justice system.

In just one example, in 2015 a college-educated African American woman named Sandra Bland was arrested in Texas after a minor traffic stop turned into a confrontation. Three days later, Bland died in jail in a suspicious death that was ruled a suicide.

After hearing the dash-cam audio of the incident, Holliday and fellow linguists Rachel Burdin and Joseph Tyler analyzed it and wrote an article, “Sandra Bland: Talking While Black,” that was published by Language Log, a linguistics blog hosted by the University of Pennsylvania.

With the help of linguistics tools such as the software program Praat and spectrograms that provide visual representations of variation in pitch, the researchers argued that the state trooper and Bland were, in essence, speaking different languages.

“What we did is we went through and used this annotation system, and we coded where the phrases are broken up and where the pitch moves up and down, the voice moves up and down, for each of them,” Holliday says.

“What we came to was she is using an identifiably African American tone pattern and he is not really matching her. So she starts in one place. He starts in another place. And it’s clear that as the situation escalates, he’s increasingly interpreting her as disrespectful, hostile, something like that. She does a few things in particular where she uses these kinds of tones, where her voice falls and rises on the same syllable. This is a pattern that we see more frequently with African American speakers.

“With the officer, he doesn’t really do that at first, but as he moves through the interaction with her, he starts to be more like that. So we think there is a mismatch in his expectations of what she was supposed to sound like as a respectful citizen. But this mismatch is fundamentally about the fact that she speaks African American English and he doesn’t.”

Bland died in jail after an incident that appeared to start with no more than a failure to signal. Her family ultimately sued, settling a wrongful death suit for $1.9 million. A misdemeanor perjury charge against the state trooper, Brian Encinia, was dismissed after he surrendered his law enforcement license and agreed not to work in the field again.

Another prominent case examined by linguists is the outcome of the trial in the shooting death of unarmed Black teenager Trayvon Martin in Florida in 2012. George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch volunteer, was acquitted of second-degree murder and manslaughter in Martin’s death.

In a paper titled “Language and Linguistics on Trial,” Stanford University Professor John Rickford, now retired, and co-author Sharese King, now an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, argued that the testimony of key prosecution witness Rachel Jeantel, a 19-year-old Black teenager, was dismissed as not credible because she spoke in African American English, contributing to the not-guilty verdicts. Jeantel was on the phone with Martin as the incident unfolded.

“They lay out all of these moments where she’s using these features of African American English that could clearly be misinterpreted by people unfamiliar with the variety,” Holliday says. “So basically, she’s speaking really differently than the lawyers, than the jury, than the public.

“There are a number of features of African American English that Jeantel employs that may be unfamiliar to mainstream listeners. For example, Rickford and King point out the use of ‘zero copula’, or the omission of the overt ‘is’ or ‘are’ verb in a sentence. Jeantel also uses differences in use of plural and possessive forms, which are also forms that may distinguish African American English from mainstream varieties.”

Jeantel’s testimony included phrases incorporating those styles, and some listeners may be unable or unwilling to hear beyond a highly socially stigmatized way of speaking.

“So when you hear somebody speak this way and you have these biases, you might just say, ‘Oh, this person is not educated and I’m going to stop listening,’” Holliday says.

“People attach a lot of judgments about morality and character to the way that people talk. And these biases that we have are almost always racist, classist, sexist, problematic in some other way, but it’s not the fault of the language. The language just varies. And that’s a natural part of what language does. But the variation gets interpreted as a problem.

“It’s very transparent that people’s ideas about language aren’t really about language,” she says. “They’re about other sociological phenomena.”