The Great Debate

Mark Wood’s column, “When Bad Things Happen,” marks the first time I’ve been truly angered by something I read in Pomona College Magazine. While one doesn’t expect hard-hitting journalism from a publication whose main purpose is to stroke alumni and encourage donations, this was beyond the pale.

Comparing Pomona’s controversy over the firing of undocumented workers, many of whom were trying to unionize (a facet of the story Wood mysteriously omitted) to the disturbing events at Penn State, Wood waxed poetic about “when bad things happen to good institutions.” With all the subtlety of Rush Limbaugh on meth, he implied that it was somehow unfair and prejudicial not to “imagine good, caring thoughtful people agonizing over intractable problems,” suggesting that a failure to do so was the moral equivalent of blaming people with cancer or AIDS for their illness.

It’s hard to imagine a more offensive and intellectually dishonest argument. What happened at Penn State was the result of people—maybe good, maybe not so good—making truly horrible decisions, in the context of a campus culture that placed certain programs on a pedestal. It appears that seriously horrible decisions have also been made at Pomona. Whether they were in fact made by “good, caring, thoughtful people agonizing over intractable problems” remains at best a matter under dispute. In any case, good intentions are hollow without good judgment.

The decision to delay a more thorough examination of the firing controversy until the next issue was understandable, given the deadlines and lead times of a quarterly publication. To publish Woods’ apologia in the interim suggests strongly that the whitewash is well under way.

—Bruce Mirken ’78

San Francisco, Calif.

I’d like to compliment you on your article “When Bad Things Happen.” It gives proper perspective on an unfortunate situation. It reflects the thought and care I would wish of all journalists. Keep it up!—Bob Hatch ’51

Laguna Woods, Calif.

I am writing in response to President Oxtoby’s winter letter to alumni lamenting the termination of 17 college employees after the worker documentation investigation.

Few take pleasure in terminating employees. However, your sympathy may be misplaced, and your willingness to use scarce college resources to support the discharged employees seems inappropriate and misguided. While the intent of the discharged employees in working illegally may have been benign—a better life for them and their families— the results of their action were harmful:

—They broke the laws of our country by entering illegally;

—They secured employment under false pretenses and in violation of the law;

—They compromised the integrity of Pomona’s hiring practices and, thereby, stained the reputation of the College;

—They placed themselves ahead of the millions who are attempting to immigrate legally into the country;

—They deprived U.S. citizens and legal residents of employment opportunities.

Perhaps, unemployment is not an important issue for the college staff and faculty, but unemployment in California has been running over 10 percent, and at a much higher rate among African Americans. By hiring illegal immigrants,

Pomona does nothing to relieve the suffering of the unemployed. Do you not think that the College has greater obligations to our own citizens than to those who have broken our laws and violated our trust?

I strongly urge that you renounce the misguided decision to provide health insurance to the discharged employees through June 30 and, instead, use the funds for an outreach program to potential replacement employees who are citizens or legal residents, especially African Americans.

—George Zwerdling ’61

Carpinteria, Calif.

I sent this to President Oxtoby in response to his alumni/ae letter about the pain of firing undocumented college workers: Responding to the dilemma of your valued long-term employees, who happen not to be citizens, doesn’t seem so difficult an issue to me at all, if the institution has any ability to take a moral stand.

Declare Pomona College a sanctuary. Defy the damn racist law. Think of the university grounds in Mexico during 1968, declared sanctuary until the army violated it. Think of the European countries that allow non-citizens not only to reside and work, but to vote! I could go on and on and we’d inevitably end up with Jim Crow, the internment of Japanese-Americans and the anti-Jewish laws in Germany, so I won’t. Still, firing the employees without a struggle is shameful.

—John Shannon ’65

Topanga, Calif.

The Life of Liffey

Like Jake Smith ’69 (“Class Notes” Spring 2012) I was moved by the article in the Fall 2010 PCM to seek out the complete series of Jack Liffey novels by my classmate John Shannon. John and I were dorm neighbors in Walker Hall freshman year, but had little contact after that and none since graduating in 1965. Finding all of the books was made possible by Amazon’s network of sellers of used books. Some of the earlier titles are actually library discards.

I enjoyed all of the novels, some inevitably more than others, but wouldn’t hesitate to recommend the whole series, preferably read in order. The stories are well-told, the characters exceptionally well-drawn and the Los Angeles milieu fascinating. It is the latter that has drawn comparisons with Raymond Chandler, but because of the sense of history and the uncompromising social criticism I am more reminded of James Ellroy. But John’s voice is very much his own and he is driven more by indignation, where Ellroy is driven by paranoia. For a sometimes dark but always convincing vision of the hometown I left nearly 40 years ago, thank you PCM, thank you Amazon and especially thank you, John.

—Steve Sherman ’65

Munich, Germany

A Sagehen Star

I just received your spring ’12 “racing issue.” Unfortunately, it appears to be missing an alumnus story that should have been included. I’m referring to the professional track career of Will Leer ’07. Let me say up front that I’m biased. I’m the managing editor of Track & Field News, a monthly magazine that covers the elite end of Leer’s sport at the world, U.S. national and high school levels.

Will is a professional middle distance runner and aspiring Olympian, specializing in the 1500 meters, although he is now starting to explore the 5000 meters. At the ’08 Olympic Trials, he placed fourth (three make the team). At the USATF National Championships in the years since he has never placed lower than fifth. The ’09 and ’11 nationals served as trials for the World Championships, and last year Will missed a qualifying spot by 0.01 second. In 2010 at the USATF Indoor Championships, Will placed second and went on to represent the U.S. at the World Indoor Championships in Doha, Quatar.

Will spent this winter training and racing in New Zealand and Australia with training partner Nick Willis, the Beijing 1500 meters silver medalist, and other members of their training group. He spends his summers racing on the pro circuit in Europe.

Hopefully when your summer issue comes out Will Leer will be a London-bound Olympian, although this year’s 1500-meter Olympic Trials final should be as tough a nut to crack as the event has ever seen in the U.S. The story of a Sagehen competing at the highest level in his sport is compelling either way, if you ask me.

—Sieg Lindstrom ’84

San Francisco, Calif.

In Memory of David Waring

We our hoping to establish an endowed scholarship fund to memorialize our late son, David A.T. Waring ’03, who passed away at the age of 29 from the ravages of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), “an acquired neurological disease with complex global dysfunctions.” David—who played a riveting lead guitar in his college band, “Dave and the Sweatpants”—had planned to study applied mathematics and music in a graduate program before he was stricken with ME/CFS just four days after his 23rd birthday.

The scholarship would be awarded to an incoming freshman whose dream of applying science/ mathematics to an understanding of music reflects Dave’s passion. We welcome contributions from the Pomona College and the wider communities to honor our late son. Donations, which are tax-deductible, may be made to the following:

The David A. T. Waring ’03 Memorial Scholarship Fund, c/o Don Pattison, Director of Donor Relations, Pomona College, 550 North College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711.

—Alan and Pat Waring

Parents of David

Irvine, Calif.

Missing Meg Worley

During the 2011–12 academic year, Pomona College lost superstar English Professor Meg Worley to Colgate in New York. From the perspective of alumni, it happened quietly. After a protracted tenure-consideration process ended in a surprising “no,” Professor Worley decided to head east. For us English alumni, it is a sad way to say goodbye to a faculty member who provided so much stability and guidance during a period of significant changes in the English Department. From 2004 to 2011, Professor Worley saw a number of fellow English professors retire, move, or pass away (including many of the department’s institutional names: Martha Andresen, Paul Saint-Amour, David Foster Wallace, Steve Young, Rena Fraden and Cristanne Miller). During this time, her dynamic classes, patient mentoring and professionalism reinvigorated the department and it was no surprise to us when, in 2010, she won the Wig Award—the highest honor bestowed on Pomona faculty.

We would like to thank Professor Worley wholeheartedly for organizing the first senior-seminar colloquium and night readings of Beowulf; for spicing up course readings with non-traditional literary texts such as graphic novels, Arthurian myth and the Bible; for offering her grammatical expertise, without judgment, whenever the need arose; for writing countless letters of recommendation for graduate school; for always keeping her office open for impromptu visits; and for expecting a lot from students but giving back so much more. In short, she represented the best of what Pomona advertises about its instructors: individualized attention, warmth and high-level intellectualism without pretension. She was a professor who brought creativity and energy to every endeavor she undertook. As one former student wrote, “No one could mistake a Meg-graded paper as you knew any assignment would be returned, every word read, and marked with one of her colorful array of pens and extraordinarily neat handwriting.” She learned our names, kept in touch after we graduated and invited us to lunch when we returned to campus for a visit. Professor Worley was a reason to stay connected with Pomona and we are so sorry that future Sagehens will miss the opportunity to learn why.

All our best to you in New York, Meg! We should have kept you, but here’s to new beginnings:

“Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote…”

—Carlo Diy ’06

—Emily Durham ’07

—Meredith Galemore ’06

—Coty Meibeyer ’05

—Carolyn Purnell ’06

—J.B. Wogan ’06

Editor’s Note: The letter was signed by seven additional alumni.

Alumni and friends are invited to email letters to pcm@pomona.edu or to send them by mail to

Pomona College Magazine

550 North College Ave.

Claremont, CA 91711.

Letters are selected for publication based on relevance and interest to our readers and may be edited for length, style and clarity.

When Karen Gerstenberger ’81 holds a quilt in her hands, she sees more than red and purple and blue and more than crisscross lines of thread. She sees the patterns that grief can make on the lives of patients and families. She imagines a young face, cradling the blanket they may receive on their first day of cancer treatment at a Seattle hospital.

When Karen Gerstenberger ’81 holds a quilt in her hands, she sees more than red and purple and blue and more than crisscross lines of thread. She sees the patterns that grief can make on the lives of patients and families. She imagines a young face, cradling the blanket they may receive on their first day of cancer treatment at a Seattle hospital.

Is there any reason for today’s academic institutions to encourage the pursuit of answers to seemingly frivolous questions? The opinionated business leader who does not give a darn about your typical liberal arts classes “because they do not prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s work force” might snicker knowingly here: Have you seen some of the ridiculous titles of the courses offered by the English/literature/history/(fill in the blank) studies department at the University of So-And-So? Why should any student take “Basket-weaving in the Andes during the Peloponnesian Wars”? What would anyone gain from such an experience?

Is there any reason for today’s academic institutions to encourage the pursuit of answers to seemingly frivolous questions? The opinionated business leader who does not give a darn about your typical liberal arts classes “because they do not prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s work force” might snicker knowingly here: Have you seen some of the ridiculous titles of the courses offered by the English/literature/history/(fill in the blank) studies department at the University of So-And-So? Why should any student take “Basket-weaving in the Andes during the Peloponnesian Wars”? What would anyone gain from such an experience? Mahalia Prater-Fahey ’15 knew that she was going to be returning home to San Diego at the end of the spring semester. Thanks to her own timely goal, she got to bring her whole team with her too. Prater-Fahey scored the game-winning goal in triple-overtime as the Sagehens earned the SCIAC championship with a 12-11 win over Redlands, earning a bid to the NCAA Tournament, hosted by San Diego State.

Mahalia Prater-Fahey ’15 knew that she was going to be returning home to San Diego at the end of the spring semester. Thanks to her own timely goal, she got to bring her whole team with her too. Prater-Fahey scored the game-winning goal in triple-overtime as the Sagehens earned the SCIAC championship with a 12-11 win over Redlands, earning a bid to the NCAA Tournament, hosted by San Diego State.

Conceived in 1937 at the College’s 50th anniversary, the house is a two-thirds scale look-alike of Ayer Cottage in the city of Pomona, where the College held its first classes in the spring of 1887.

Conceived in 1937 at the College’s 50th anniversary, the house is a two-thirds scale look-alike of Ayer Cottage in the city of Pomona, where the College held its first classes in the spring of 1887.

During his Pomona College days, Dan Hickstein ’06 landed a prestigious

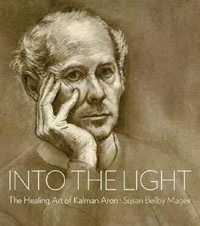

During his Pomona College days, Dan Hickstein ’06 landed a prestigious  The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images.

The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images. “I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.”

“I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.” On the first day of his Critical Inquiry class, Linguistics and Cognitive Science Professor Michael Diercks strolled into the room, looking very much like any other college student, wearing a plain T-shirt and a pair of jeans. He sat down among his students and introduced himself as Michael. After engaging in conversation with his “classmates” about how late the professor was, he finally introduced himself to the class as their teacher. An awkward silence fol- lowed. And then some nervous laughter. What did they expect? This was a class on social awkwardness!

On the first day of his Critical Inquiry class, Linguistics and Cognitive Science Professor Michael Diercks strolled into the room, looking very much like any other college student, wearing a plain T-shirt and a pair of jeans. He sat down among his students and introduced himself as Michael. After engaging in conversation with his “classmates” about how late the professor was, he finally introduced himself to the class as their teacher. An awkward silence fol- lowed. And then some nervous laughter. What did they expect? This was a class on social awkwardness! Set on enlisting Pomona student musicians to give free lessons to kids, Gabriel Friedman ’12 landed a $10,000 grant from the Donald A. Strauss Public Service Foundation to help pay for cellos, violins and other instruments. But his path to becoming a music mentor began long before that:

Set on enlisting Pomona student musicians to give free lessons to kids, Gabriel Friedman ’12 landed a $10,000 grant from the Donald A. Strauss Public Service Foundation to help pay for cellos, violins and other instruments. But his path to becoming a music mentor began long before that:

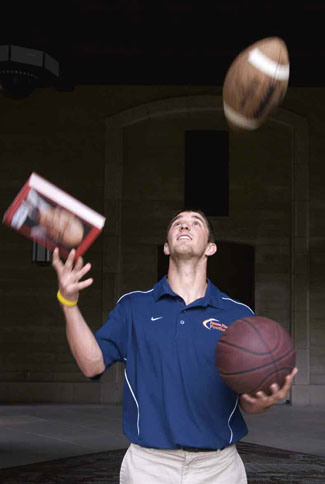

“One of my teammates was supposed to bring my jersey for me, since I couldn’t go on the team bus,” Maki says. “Then I got to Pepperdine, and unfortunately he had forgotten it. So I had to call Jake [Caron PI ’11], and he drove it up to Malibu and finally got it to me just before halftime.” Maki ended up playing six minutes in the second half, as the Sagehens gave the Waves a run for their money before falling 59-50. “I can’t say too many people have ever had a day like that,” says Maki.

“One of my teammates was supposed to bring my jersey for me, since I couldn’t go on the team bus,” Maki says. “Then I got to Pepperdine, and unfortunately he had forgotten it. So I had to call Jake [Caron PI ’11], and he drove it up to Malibu and finally got it to me just before halftime.” Maki ended up playing six minutes in the second half, as the Sagehens gave the Waves a run for their money before falling 59-50. “I can’t say too many people have ever had a day like that,” says Maki.