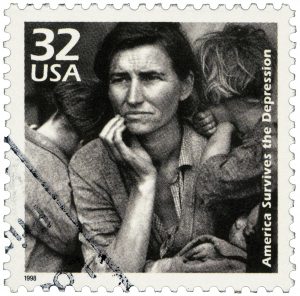

We’re shaped by the crises of our times—especially those that happen when we’re young. Looking back on my parents’ lives with the relative wisdom of age, I can see the currents that carried them, turning them into the people I knew.

They were both children of the Great Depression, and the marks of that experience were stamped into their psyches in ways that seem obvious to me now. Both were rural Southern educators—poor, but not as poor as others, and nowhere near the poverty they had both known in their youth. As a preteen, I helped mix the cement for the foundations of the house my dad was building with his own hands. Year after year, we mapped out summer road trips out West that never happened. I spent hours playing with armies of inverted tacks, arrayed for war in static ranks and files. I never knew plenty, but I never knew want. Maybe that’s why I never really understood that we were poor.

But as I grew older, I saw how my parents always saved money from their meager incomes. Even after retirement, living on a thin thread of Social Security and my Dad’s veteran’s pension, they always managed somehow to put something aside. Not for some well-earned extravagance, but as a hedge against that second Great Depression that, fortunately, never came.

They were also shaped by World War II—especially my dad, who nearly died on a battlefield in eastern France. I remember the little bits of shrapnel that would well up, infrequently but painfully, through his scars, but it wasn’t until much later that I came to understand why a man who, in his teens, played his guitar and sang in movie theatres as a pre-show entertainer wanted nothing more, the rest of his life, than to be left alone with his books and his thoughts.

As a whole, my generation of Americans, and others since, have lived in comparatively fortunate times. Wars, but no world wars. Recessions, but no depressions. The poor were still poor, and the disadvantaged were still disadvantaged, but there were no global catastrophes to make their load even heavier.

Until now.

For the past eight months, I’ve been one of the lucky ones. I have a job I can do from home. My family is safe and well—knock on wood. As a bit of a loner, I’ve adjusted fairly well to isolation. The internet and delivery services have partially filled the void where outside activities used to be. For me, the pandemic has brought fear and boredom and inconvenience and physical separation from friends and loved ones, but not overwhelming loneliness or inconsolable grief or the daily peril faced by first responders and essential workers.

But as my wife and I go out for our masked walks around the neighborhood, crossing the street to avoid meeting other pedestrians, I can’t help but wonder what this is doing to us all on the inside. The slow remolding of our psyches, the imperceptible formation of walls and sinkholes inside our heads. The Great Depression turned my mom into a lifelong miser. World War II turned my dad into a recluse. What is this seemingly endless pandemic doing to me?

And more importantly, what is it doing to my 5-year-old grandson?

It would be nice to think that when this is over, it will really be over. But I suspect that we’ll be talking about the lasting effects of 2020 for many years to come. There will be a new normal, and some of it will be good—maybe even wonderful—but some of it will definitely be abnormal in ways we can, for now, only guess.