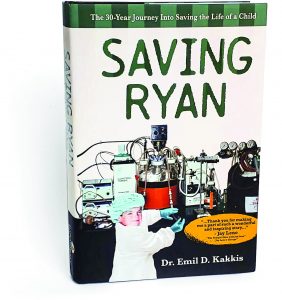

In Saving Ryan, physician-scientist Emil Kakkis ’82 chronicles the 30-year journey to develop a first-ever treatment for the ultra-rare genetic disease mucopolysaccharidosis, known as MPS. At the center of the story are Ryan Dant, who was diagnosed with potentially fatal MPS type I at age 3, and his parents, who started a foundation to support the development of the treatment. Dant is now in his 30s, a college graduate and recently married.

PCM’s Lorraine Wu Harry ’97 talked to Kakkis—also founder, president and CEO of the biopharmaceutical company Ultragenyx—about the book, his time at Pomona and advice for young people today. The interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

PCM: What was your impetus for writing the book? Who do you hope will read it?

Kakkis: One impetus was to capture the challenge of getting a treatment for rare disease developed from a policy perspective, to highlight the requirements the Food and Drug Administration has put that are quite difficult, near impossible. While we succeeded, it was so close to being missing. It shouldn’t have been because it’s straightforward science. I intended the book to help with the FDA and Capitol Hill on the policy issues regarding the regulation of these rare disease drugs. At the same time, I wanted to capture for families out there that the impossible can be achieved, that you don’t have to be a scientist—Mark Dant was a police officer, and his wife was a programmer—that you can come together and figure out how to treat your kid. It was a story for inspiration for those families.

PCM: Did you keep journals along the way? There are so many details you remember from the last 30 years.

Kakkis: Some of them were seared into my brain. I remember them very specifically. I had memos and letters that helped me place things in time. What the book does is jump from moment to moment in time. I was really writing about the things that were memorable. Things like an FDA meeting. That meeting I remember very, very vividly.

PCM: Tell me about your time at Pomona: what you studied, how it shaped you, how it prepared you for your work.

Kakkis: I spent my time at Pomona as a biology major. I took a lot of chemistry, biochemistry and a fair amount of philosophy too. I took a course with [Professor Fred] Sontag when I was a freshman. I thought I was a good writer, and then I discovered that I was not a good writer. Sontag had a great policy. You wrote your first paper; he graded it and he graded it thoroughly. If you rewrote the paper based on the comments, then he would grade the new one too and average it with your first draft. I ended up rewriting every single paper. What he was doing was encouraging you. It started me thinking about how to express yourself and how to edit yourself. How to think ahead, how things sound, how they read. It was a really important piece of learning.

The science training was, of course, excellent. As an undergrad I was running the research; there wasn’t a grad student. Therefore, you had to learn and organize the research yourself and conduct experiments and plan what you were going to do. It’s a good test for your ability to organize and execute, which serves you well later. You’ve done it before, as opposed to being a helper on someone else’s project where you’re just following along. Having to do it yourself as an undergraduate researcher challenges you to think harder, deeper and to be able to plan and execute an actual research program.

PCM: Would you have any advice for Pomona students who are either aspiring physicians or scientists, or both?

Kakkis: The important thing that I put in the book is the discovery of your true purpose for your career. It shouldn’t be about money, or fame or prizes. It should be, what do you want to do that’s going to be meaningful, that will last and be important?

In college, you have a lot of reasons why you might become an M.D.-Ph.D. Finding your true purpose will help you make better decisions as you go forward that are not about your fame or about money but about doing the right thing that helps achieve something lasting. You could talk about prizes or tenure, but there’s nothing quite like talking with Ryan or meeting him, finding out how he’s doing and realizing that you’ve changed the course of his life and the lives of many other kids with MPS I. There’s a real purpose to what you can get done in research if you find that purpose. And if you adhere to it, then you can have a career that’s without regret and achieve great things.

PCM: What has been the reception to your book?

Kakkis: The reception has been really good. I’m happy I got it done because at least the story is down on paper. The truth is, like any movie or writer, there are always imperfections you wish could be better, but I do feel it captures the story enough that others can relive it and maybe draw from it what it takes to do the impossible and how gratifying and exhilarating it can be.

PCM: I could see it becoming a movie.

Kakkis: That’s right. I’m going to be lobbying for George Clooney to play me. He was a great pediatrician on ER; he needs to be a pediatrician in the movie. He’s done everything else. He’s been a lawyer and other things. It’s time for him to be a doctor again.

PCM: Any last things you’d like

to share?

Kakkis: You always wonder what you can do with your life. I’ve run into students lately, especially post-pandemic, that feel like there’s nothing that they want to do or nothing great, no place to go. The truth is, there are incredible projects that are waiting for them that they’ve never heard of, that they can find, that will give their life great meaning and purpose. They should keep searching for that thing and find that passion and that purpose and do great things. You may not have any idea what it is—I certainly had no idea when I was in college, but it came out, it was found. I hope people get the inspiration to seek that mission and find their purpose. Even though you have no idea what it is now, it will come, and then you have to see it in front of you and know when it’s time that this is the thing I need to do.

Tene Ariyo ’26, women’s volleyball

Tene Ariyo ’26, women’s volleyball Yafae Cotton ’26, football

Yafae Cotton ’26, football Joya Terdiman ’26, women’s cross country

Joya Terdiman ’26, women’s cross country