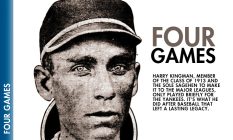

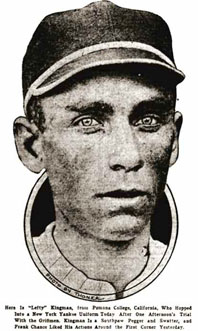

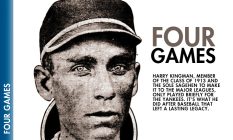

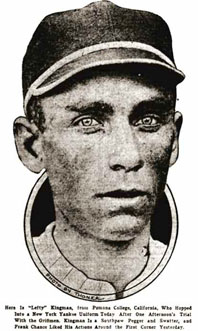

Harry Kingman struck out in his very first at bat for the New York Yankees and, decades later, he would still recall the walk back to the dugout as “long and grim.” His major league career, on the other hand, was short. An athletic superstar at Pomona, where he graduated in 1913, and the first and only Sagehen to make it to the major leagues, Kingman would appear in only four games of the 1914 season—just a historical footnote, really.

It’s what he did with his life after Major League Baseball that was extraordinary. His remarkable career took him to China, where he started speaking out after a student massacre. His willingness to stand up for the voiceless carried on to UC Berkeley and the frontlines of the battle for free speech, civil rights and affordable student housing, then to Washington, D.C., where he was an underdog lobbyist. His work drew the attention of The New Yorker, and words of praise from luminaries ranging from Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi to Peace Corps Director Sargent Shriver.

“We are all deeply indebted to Harry Kingman—such men are almost unique,” wrote Earl Warren, during his time as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. “Few have given so much of their lives to ensure man’s birthright of equality and liberty.”

“We are all deeply indebted to Harry Kingman—such men are almost unique,” wrote Earl Warren, during his time as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. “Few have given so much of their lives to ensure man’s birthright of equality and liberty.”

Kingman’s accomplishments must have surprised people who met the rowdy preacher’s kid in his early years. He was born in 1892 in Tientsin (Tianjan), China, as part of a long line of missionaries. As his father’s health deteriorated and Chinese soldiers began marching by the school where the minister taught, in a prelude to the Boxer Uprising, the family moved to Claremont.

The elder Kingman became pastor of the Congregational Church and a trustee of Pomona College. When Harry rebelled as a teenager, smoking and shooting pool—he could run up to 40 balls in a straight pool—his parents shipped him to military school, where he was expelled for fighting. “I … wasn’t getting along well and I didn’t think I was going to amount to much. I was unhappy, very unhappy,” he recounted in an oral history that reveals a humble man, with a wry sense of humor and strong sense of justice.

At his father’s urging, he attended a YMCA conference where he vowed to change his life. He entered Pomona, where he excelled in basketball, track, swimming, tennis and baseball. Captain of the baseball team, Kingman was dubbed by the Los Angeles Times as “the heaviest hitter ever developed in the southern end of the state.” But he also fell behind in his studies. Once, a professor offered to give Kingman a test Saturday morning to make up for failing grades. If he passed, he could play in the game that afternoon.

“My father and the fans and everybody would be out there at the ball park…waiting to see whether Pomona was going to have Harry Kingman pitching or not,” recalled Kingman, who also played first base. “When I would show up in my suit, you know, they would applaud, and I would be in the game. But it was pretty uncertain.”

On summer break, Kingman worked as an assistant bricklayer on Pomona’s dormitories, climbing up tall ladders and earning 17 and a half cents per hour.

After graduating as a history major, he embarked on his brief professional baseball career signed on by the Washington Senators, then quickly traded to the New York Yankees, who wound up using him a few times as a pinch hitter. He only played on the field once, at first base, notes his biography with the Society for American Baseball Research.

Unsatisfied warming the bench, Kingman left the Yankees in 1916 and joined the staff of Stiles Hall, UC Berkeley’s off-campus student branch of the YMCA, because he wanted to help disadvantaged youth. Yet he was never far from the sport.

A year later, he was drafted and sent to Camp Gordon in Atlanta, where he was captain of the varsity baseball team. The commanding general told Kingman, an infantry officer, to put together the best service ball club in the nation. The general protected the team members, preventing their deployment. World War I ended the following summer and his initial disappointment over not being in combat turned to pacifism.

Victory hadn’t made the world safe for democracy. In 1921, Kingman sailed for China as a missionary and student sports coach. “When I first went to China … I did it primarily with the idea of helping its people. But very soon it dawned on me I had something to learn from the citizens of a nation with a long and respected civilization.”

He sent for his fiancée, Ruth, also the child of missionaries, and their daughter was born in 1924—the fourth generation of the family to live in China. He also began writing short mimeographed newsletters on Chinese politics that drew admiration from novelist H.G. Wells and the British philosopher Bertrand Russell, among many prominent thinkers and leaders.

While playing baseball on a spring day in 1925, Kingman noticed a huge traffic jam on the main boulevard in Shanghai. Police officers in the foreign-controlled section of the city had opened fire on Chinese demonstrators, killing and injuring dozens, including a promising student Kingman coached. In a letter to a local newspaper, Kingman defended the students and their right to protest foreign exploitation, which drew a flood of angry replies from the expat community. Within a month, he was pushed out and transferred to Tientsin (Tianjin), his birthplace, in the heart of warlord country.

It was the first time the Kingmans had come up against such unrelenting opposition, and the experience seared the couple, sensitizing them when they fought years later for the rights of minorities.

In the winter of 1927, on his way back to Berkeley, he stopped in Japan for a month to coach baseball in Osaka. He then returned to the student YMCA, Stiles Hall, began coaching Cal’s junior varsity baseball squad, and worked on social justice and free speech issues that resonated for decades.

Stiles Hall started hosting left-wing students who weren’t permitted to meet or speak on campus. During the Great Depression, he helped establish a housing co-operative where students contributed their labor to cut down expenses. (In the 1960s, Barrington Hall, one of the earliest co-ops, became the epicenter of the Berkeley free speech and anti-war movements.)

From their inception, the co-ops broke down prejudice by allowing different races to live together, unusual in the 1930s. As a Berkeley undergraduate, Yori Wada worked as a houseboy, unable to find a landlord willing to rent to a Japanese-American. “I remember knocking on the doors of houses that had signs saying, ‘Rooms for Rent,’ but the turndowns were universal,” Wada told the San Francisco Chronicle. Wada, who later became a University of California Regent, praised Kingman for opening doors for minorities.

Kingman credited his experience of living as a child in China, playing with black athletes, and the attitude of his parents for growing up without prejudice. “[My father] gave me the idea that people should try to stick up for and help the underdog or the person that is getting a bum deal and that the stronger person should stand up for the weaker person.”

When the United States entered World War II, the Kingmans opposed the government’s evacuation of Japanese on the West Coast to internment camps, with wife Ruth taking the lead. Meanwhile, Harry was appointed as head of the West Coast office of a federal commission to combat racial employment discrimination at defense contractors.

“Their interests and causes had a national and even international focus —racial justice, civil rights— but they had day-to-day impact on the people within their own community,” says Charles Wollenberg, a historian who teaches at Berkeley City College.

Kingman’s niece, Claire Mc- Donald, ’47, who followed the couple into public service for three terms on the Claremont City Council, says Harry and Ruth taught her: “You participate in government if you can. You don’t sit at home and complain. You go out and change the world.”

Kingman retired from Stiles Hall in 1957, but his career went into extra innings: he and his wife formed the Citizens’ Lobby for Freedom and Fair Play—a two-person volunteer civil rights lobby—and moved to Washington, D.C. “We could have lobbied in Sacramento,” he told Coronet magazine in 1961. “But I always liked the big leagues best. That’s where they play the best ball.”

In those years, Kingman was described in a New Yorker piece as raw-boned and sun-tanned, with a gravelly, drawling soft-spoken voice, still moving with an athlete’s grace. Harry and Ruth were oddities in the capital. The two senior citizens living off his pension and Social Security, were beholden to no corporate interests, with no bottomless expense account. They invited guests to “California patio suppers,” a big pot of spaghetti and green salad, served on a red-and-white checked tablecloth and paper plates.

Baseball also helped Kingman find common ground in Washington, D.C., when he coached the Democrats in an annual game against the Republicans. In a class note Kingman submitted to this magazine during that time, he wrote: “We operate on a shoestring, but never had more friends nor experienced a more exciting, adventurous and satisfying experience. This week my friend Billie [sic] Martin, of big league fame, visited me on Capitol Hill, and I had the fun of introducing him around. Senators ganged around him.”

Harry and Ruth lobbied hard for the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. They were at the office doors when congressional leaders first arrived in the morning and the pair kept making the rounds late at night. Opponents, meanwhile, launched into a Senate filibuster that included a 14 hour and 13 minute address. From the crowded gallery, Kingman held his breath as Sen. Clair Engle, a Democrat from California, was carried in for a cloture vote, a procedure in which the Senate can place a time limit on the consideration of a bill. Ill with a brain tumor, Engle, who could not speak, raised his crippled arm for an affirmative vote—breaking a Senate filibuster against a civil rights bill for the first time in history.

Kingman wept, overjoyed.

His creed was simple: “to be for something or somebody, not merely against,” he told Edward R. Murrow on his famed radio program, This I Believe.

In 1970, the couple returned to Berkeley, where the student co-op he helped to create kept growing. (Today 1,300 student members live or eat at 20 co-ops.) Later that decade, a newly-acquired co-op residence was named Kingman Hall to honor Harry. In covering the dedication, the Chronicle called the then-elderly activist “an inspiration to thousands of University of California students. Harry Lee Kingman has lived the kind of life boys read about at the turn of the century.”

Just a few years later, in 1982, Kingman passed away at the age of 90. “I have never felt like I had any great ability. I’ve known so many people who had much better brain power than I ever had,” Kingman once said. “But I’ve kept on the job…. I’ve never stopped trying to become more effective and to show my gratitude to God.”

In his paper, “The Baseball Hall of Fame is Not the Kiss of Death,” Smith has debunked research that purported to show getting into Cooperstown would shorten a player’s life expectancy. He also has taken apart a study that suggested major league players with names that start with “D” die younger than others. (Derek Jeter really should send Smith a fruit basket.) Ditto for another piece of research that concluded players with negative initials (think ASS) die younger than players with positive initials (think ACE).

In his paper, “The Baseball Hall of Fame is Not the Kiss of Death,” Smith has debunked research that purported to show getting into Cooperstown would shorten a player’s life expectancy. He also has taken apart a study that suggested major league players with names that start with “D” die younger than others. (Derek Jeter really should send Smith a fruit basket.) Ditto for another piece of research that concluded players with negative initials (think ASS) die younger than players with positive initials (think ACE). Whether it’s a practice or game day, Raye Calderon and his crew are always first to arrive at Pomona’s Alumni Field. During the season, daily maintenance of the ballpark requires about as much time as it takes to play a game. Scrape, pack, rake, repeat. Grooming the field just right helps prevent bad hops of the ball that can lead to injuries. “We’re trying to keep our players in good condition without any black eyes or fat lips,” says Calderon, who has been maintaining the field for more than three decades.

Whether it’s a practice or game day, Raye Calderon and his crew are always first to arrive at Pomona’s Alumni Field. During the season, daily maintenance of the ballpark requires about as much time as it takes to play a game. Scrape, pack, rake, repeat. Grooming the field just right helps prevent bad hops of the ball that can lead to injuries. “We’re trying to keep our players in good condition without any black eyes or fat lips,” says Calderon, who has been maintaining the field for more than three decades. Work begins at home plate, which today is a mess after an April shower. Somebody played ball in the mud after the rain, leaving imprints for Calderon and Co. to fill in. Then it’s on to the pitcher’s mound, packed hard with clay that arrives by truck from Corona. Next he works the base paths, groomed with crushed red brick—but not too much. Calderon doesn’t want the infield to feel “like a litter box.” He aims to make Alumni Field, where the oak-studded Wash provides a bucolic backdrop, the kind of diamond he would want to play on.

Work begins at home plate, which today is a mess after an April shower. Somebody played ball in the mud after the rain, leaving imprints for Calderon and Co. to fill in. Then it’s on to the pitcher’s mound, packed hard with clay that arrives by truck from Corona. Next he works the base paths, groomed with crushed red brick—but not too much. Calderon doesn’t want the infield to feel “like a litter box.” He aims to make Alumni Field, where the oak-studded Wash provides a bucolic backdrop, the kind of diamond he would want to play on.

“We are all deeply indebted to Harry Kingman—such men are almost unique,” wrote Earl Warren, during his time as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. “Few have given so much of their lives to ensure man’s birthright of equality and liberty.”

“We are all deeply indebted to Harry Kingman—such men are almost unique,” wrote Earl Warren, during his time as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. “Few have given so much of their lives to ensure man’s birthright of equality and liberty.” In his baseball-loving boyhood, Don Daglow ’74 used to get calluses on his fingers from flicking the spinner for the All-Star Baseball board game that he’d play again and again, sometimes eight times a day. Over time, he even reworked the venerable game to allow changes in pitching.

In his baseball-loving boyhood, Don Daglow ’74 used to get calluses on his fingers from flicking the spinner for the All-Star Baseball board game that he’d play again and again, sometimes eight times a day. Over time, he even reworked the venerable game to allow changes in pitching.

So did Hollywood seek out presidents or did presidents seek out Hollywood? Peretti says the answer is yes and yes. The attraction was mutual. “Presidents were fascinated by the cultural power wielded by the movies, while moviemakers were drawn to the dramatic realm of power in the real world,” says Peretti.

So did Hollywood seek out presidents or did presidents seek out Hollywood? Peretti says the answer is yes and yes. The attraction was mutual. “Presidents were fascinated by the cultural power wielded by the movies, while moviemakers were drawn to the dramatic realm of power in the real world,” says Peretti.