Picture This: Like the rest of Southern California, the Pomona campus saw unprecedented swarms of migrating painted lady butterflies this spring, due to the superbloom in the desert areas where they breed.

—Photo by Kristopher Vargas

As Sagehens around the globe—from Claremont to Hong Kong—volunteered for community service projects in honor of 4/7 Day, the campus celebration was designed for a lighter purpose—to give current students a chance to shed some of their mid-term stress. For a day—Sunday, April 7—Marston Quad took on a carnival atmosphere with everything from a zipline and a rock-climbing wall to a petting zoo and a range of food trucks—all in honor of Cecil’s favorite number, 47.

Photos by Kristopher Vargas and Jeremy Snyder ’19

Lawrence Chen ’20 knows how to raise the barre. A ballet dancer since the age of 13, Chen is able to balance his professional dancing career while also being a full-time student majoring in chemistry. This April, Chen saw his first co-authored academic article published in a prestigious chemistry journal—a major achievement for any undergraduate student. The publication of the article is the grand finale for Chen, who spent two years doing research with Professor of Chemistry Roberto Garza-López. To understand how Chen is able to rehearse for 15-plus hours (sometimes up to 40 hours a week during performance season) and do graduate-level computational chemistry research, put yourself in his ballet slippers…

Grow up listening to your mother share stories of studying ballet in Hong Kong—and how she had to give up a career in dance to support her family.

Grow up listening to your mother share stories of studying ballet in Hong Kong—and how she had to give up a career in dance to support her family.

Own a DVD of the American Ballet Theatre’s 1977 production of “The Nutcracker” starring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland and watch it over and over.

Own a DVD of the American Ballet Theatre’s 1977 production of “The Nutcracker” starring Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland and watch it over and over.

Begin to study ballet at age 13—an “extremely late” start. Decide to be home-schooled for high school courses in order to allow time to study ballet intensely at a small ballet academy.

Begin to study ballet at age 13—an “extremely late” start. Decide to be home-schooled for high school courses in order to allow time to study ballet intensely at a small ballet academy.

In addition to home-schooling, attend your local community college part time and take almost enough math classes to get an associate’s degree in the subject.

In addition to home-schooling, attend your local community college part time and take almost enough math classes to get an associate’s degree in the subject.

Participate in large competitions, like the International Ballet Competition and Prix de Lausanne, to have a chance at scholarships to ballet companies with international prestige. Learn from both your successes and your losses to work even harder.

Participate in large competitions, like the International Ballet Competition and Prix de Lausanne, to have a chance at scholarships to ballet companies with international prestige. Learn from both your successes and your losses to work even harder.

Get accepted to a number of colleges—including the University of Southern California for its dance program—but choose Pomona for its small classes and close-knit community.

Get accepted to a number of colleges—including the University of Southern California for its dance program—but choose Pomona for its small classes and close-knit community.

In your first year, enroll in a ballet class taught by Victoria Koenig, director of the Inland Pacific Ballet dance company. Get invited to audition and dance in productions of “The Nutcracker” two years in a row.

In your first year, enroll in a ballet class taught by Victoria Koenig, director of the Inland Pacific Ballet dance company. Get invited to audition and dance in productions of “The Nutcracker” two years in a row.

Take general chemistry courses and find a supportive mentor in Professor of Chemistry Roberto Garza-López, who attends a performance of “The Nutcracker” to see you dance.

Take general chemistry courses and find a supportive mentor in Professor of Chemistry Roberto Garza-López, who attends a performance of “The Nutcracker” to see you dance.

Spend your first two summers on campus, thanks to grants from Pomona and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), conducting computational chemistry research for Garza-López.

Spend your first two summers on campus, thanks to grants from Pomona and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), conducting computational chemistry research for Garza-López.

As a co-author, see your data published in Chemical Physics Letters: X, a peer-reviewed chemistry journal, during your junior year while starting rehearsals for a production of “The Little Mermaid.”

As a co-author, see your data published in Chemical Physics Letters: X, a peer-reviewed chemistry journal, during your junior year while starting rehearsals for a production of “The Little Mermaid.”

—Photo by Siggul/VAM

Leanchoiliid fossil from the Qingjiang biota —Photo by X. Zhang

These days, whenever there’s a truly earthshaking development in the world of Cambrian fossils, Professor of Geology Robert Gaines seems to find himself squarely in the middle of it. Last year, it was an article in Science called “Cracking the Cambrian,” about the latest discoveries in the fossil-rich sites that Gaines and his team unearthed in Canada’s Kootenay National Park back in 2012—considered one of the most important geological finds in recent history. This year, it’s something that may be even bigger: a 518-million-year-old fossil site unearthed in the Yangtze Gorges area of South China that may turn out to be even more important, according to a new article, also published in Science.

The new site—dubbed the Qingjiang biota—was discovered by a team of Chinese researchers in South China. It’s home to a nearly pristine and diverse 500-million-year-old fossil record that has not been impacted by metamorphosis or weathering. The diversity of its fossils may rival that of the Burgess Shale of British Columbia and the Chengjiang fossil site in China’s Yunnan province, which are considered two of the most important fossil finds of the 20th century, according to Gaines, the only American on the team that is studying the site. The new site is more than 600 miles from Chengjiang.

In addition to their high taxonomic diversity, Qingjiang fossils are characterized by near-pristine preservation of soft-bodied organisms—including juvenile or larval forms, arthropod and worm cuticles and jellyfishes—and soft-tissue features that are rarely seen in the fossil record. More than 4,000 specimens have already been collected, with 101 species identified. Of these species, 53 are so new to science that names have to yet to be assigned to them.

“This finding enriches our view of the early animal world and offers us really remarkable views of the simplest animals,” says Gaines. “One of the most incredible things about this finding is the pristine condition of many of these specimens—fossils that haven’t been substantially affected by impacts of time, and in them you can clearly see soft tissues like eyes, tentacles and gills.”

Pomona College Biology Professor Sara Olson has been awarded a prestigious Faculty Early Career Development Award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to explore the process of embryo development in roundworms. The five-year award of $827,962 will fund her study, as well as research opportunities for Pomona College biology and molecular biology students and rising high school seniors in the Pomona College Academy for Youth Success (PAYS) program.

Using fluorescence microscopy, biochemistry, molecular biology and genetic approaches, Olson’s research focuses on the nematode worm C. elegans, a roundworm, as a model organism to explore how protective barriers form around embryos. Findings from this study could shed light on early embryonic development in other species, including mammals.

“The idea of building a protective barrier around an embryo is common throughout the animal kingdom,” says Olson. “From worms to flies to fish to mammals, all of these animals build protective barriers around their embryos. We study how that barrier forms over the egg during early development. Before fertilization, it has to be porous so the egg is accessible to the sperm, but after fertilization it has to get remodeled and be closed off for protection.”

Another goal is to identify new drug targets to fight parasitic roundworm infection in humans, plants and animals. “These parasitic worms affect people in developing countries in Africa, Central and South America and Southeast Asia,” says Olson. “Parasitic nematode infections are a major burden that cause loss in agriculture, sickness in humans and loss of productivity. If we can figure out how the worm’s eggshell is built, we can also figure out how to destroy it in the parasitic worms.”

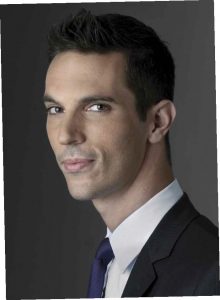

With featured speaker: Ari Shapiro, host of NPR’s All Things Considered

Ari Shapiro, host of NPR’s All Things Considered

The Ideas@Pomona Summit, Pomona’s premier lifetime learning event, is an energetic, day-and-a-half conference dedicated to bringing together Pomona College alumni, parents and friends for a weekend of meaningful connection and active dialogue around timely, newsworthy and captivating ideas. It will take place Oct. 25–26, 2019, at the Hyatt Centric Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco.

“Liberal Arts NOW and NEXT” will serve as the weekend’s theme. What does cutting-edge research tell us about the NOW and the NEXT, about who we are and where we are going? How are liberal arts values such as critical thinking and creative learning being brought to bear on today’s unique challenges and opportunities?

Featured speakers will include Ari Shapiro, host of NPR’s All Things Considered; Laszlo Bock ’93; Martina Vandenberg ’90; Liz Fosslien ’09; professors Kevin Dettmar and Nicholas Ball; and more.

The Ideas@Pomona Summit promises to curate the best content from around campus and the greater Pomona community to ignite discussion, share ideas and highlight exciting research and trends.

Registration opens spring 2019 at Ideas@Pomona Summit.

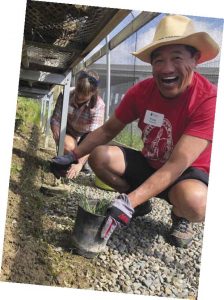

Orange County Sagehens at a 4/7 event at the Back to Natives Nursery

Sagehens turned out across the globe to celebrate Pomona’s 4/7 Celebration of Sagehen Impact. Volunteer service events as near as Claremont and as far as Hong Kong brought enthusiastic alumni and parents to the Food Bank of the Rockies, the Sacred Heart Community Service Food Pantry, Teach4HK, Special Olympics and other impactful organizations. Others chirped across Sagehen social media about the ways they are changing their communities for the better.

Start planning your #SagehenImpact for next year’s 4/7.

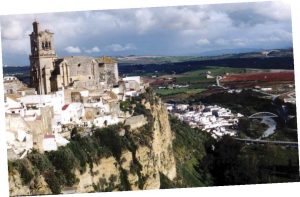

Andalucía: The Enduring Legacy of Islam

April 4 to 12, 2020

The real charm of Andalucía lies in its countryside, featuring blindingly white mountain villages (the so-called pueblos blancos) and endless olive and almond groves. Infamous for its scalding summers, Andalucía is equally renowned for its mild springs, the perfect season for enjoying the countryside the way it is meant to be enjoyed: on foot. The southernmost tip of Andalucía greets its visitors with whitewashed splashes on its craggy hillsides and minarets reshaped into Christian bell towers. Herds of wild bulls roam the upland pastures, pigs root for acorns under isolated oak trees, and Egyptian vultures soar overhead. Hike by day and enjoy village life by night in the midst of a week-long festival leading up to holiest of Christian holidays: Easter. What better way to appreciate the uniqueness of the southwesternmost corner of Europe?

The real charm of Andalucía lies in its countryside, featuring blindingly white mountain villages (the so-called pueblos blancos) and endless olive and almond groves. Infamous for its scalding summers, Andalucía is equally renowned for its mild springs, the perfect season for enjoying the countryside the way it is meant to be enjoyed: on foot. The southernmost tip of Andalucía greets its visitors with whitewashed splashes on its craggy hillsides and minarets reshaped into Christian bell towers. Herds of wild bulls roam the upland pastures, pigs root for acorns under isolated oak trees, and Egyptian vultures soar overhead. Hike by day and enjoy village life by night in the midst of a week-long festival leading up to holiest of Christian holidays: Easter. What better way to appreciate the uniqueness of the southwesternmost corner of Europe?

For complete tour information, please visit Alumni Travel Program.

Have you checked out SagePost47, Pomona’s online platform that bridges the gap between students and alumni by fostering one-on-one connections and mentorships? Founded by an alumnus and a student in 2014, SagePost47 has grown to feature 100-plus alumni mentors, blogs, panel events and mock interviews. Learn more and sign up today at SagePost47

Have you checked out SagePost47, Pomona’s online platform that bridges the gap between students and alumni by fostering one-on-one connections and mentorships? Founded by an alumnus and a student in 2014, SagePost47 has grown to feature 100-plus alumni mentors, blogs, panel events and mock interviews. Learn more and sign up today at SagePost47

47 Chirps to our Alumni Distinguished Service Award Winners

The 2019 Alumni Distinguished Service Award winners, selected by a committee of past Alumni Association presidents, are:

Phelps

Lisa Prestwich Phelps ’79 P’12, who initiated the growing tradition of regional service events for 4/7 with the first-ever such event in Seattle and has served on the Alumni Association Board and class reunion committees.

Garvey

Susanne Garvey ’74, who has served as a regional leader for Washington, D.C, an admissions volunteer over many years, and former Alumni Association president.

Epps

Faye Epps, the first to receive a special honorary Alumni Distinguished Service Award in recognition of her tenure as the administrator for Pomona’s alumni programs over four decades.

The 2019 Blaisdell Distinguished Alumni Award winners, selected by a committee of Alumni Association Board members for their contributions and achievements in their profession or community, are:

Maize

Earl Maize ’72, manager of the Cassini Program, a mission that began exploring the Saturn system in 2004 and concluded operations in 2017 with a spectacular plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere.

Ramenofsky

Marilyn Ramenofsky ’69, Olympic medalist and former world-record holder in swimming, and researcher into the physiology and behavior of migratory birds.

Schatz

Brian Schatz ’94, senior United States senator from Hawai’i, focusing on climate change, access to higher education, privacy and consumer rights, and health care.

Cleaver

Debra Cleaver ’99, founder and CEO of Vote.org, the leading nonpartisan, nonprofit organization increasing voter turnout.

Obst

Lynda Obst ’72, one of Hollywood’s most successful film and television producers, known for Interstellar, How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days, Sleepless in Seattle, The Fisher King, and Good Girls Revolt, among many others.

Seeking your next spring novel and a way to connect with fellow Sagehens? Join the Pomona College Book Club on Goodreads to chat with alumni, professors, students, parents and staff around a common love of reading. Visit Pomona College Book Club or attend an in-person discussion in your city. This spring, we will be reading Madeline Miller’s Circe, described by The New York Times as “a bold and subversive retelling of the goddess’s story that manages to be both epic and intimate in its scope, recasting the most infamous female figure from the Odyssey as a hero in her own right” and named one of the best books of the year by NPR, The Washington Post, Time, The Boston Globe and many others.

Seeking your next spring novel and a way to connect with fellow Sagehens? Join the Pomona College Book Club on Goodreads to chat with alumni, professors, students, parents and staff around a common love of reading. Visit Pomona College Book Club or attend an in-person discussion in your city. This spring, we will be reading Madeline Miller’s Circe, described by The New York Times as “a bold and subversive retelling of the goddess’s story that manages to be both epic and intimate in its scope, recasting the most infamous female figure from the Odyssey as a hero in her own right” and named one of the best books of the year by NPR, The Washington Post, Time, The Boston Globe and many others.

Pomona College Book Club of Chicago

Scott Kratz ’92 was having breakfast with a good friend, who at the time was director of D.C.’s Office of Planning, when he asked an offhand question about all the construction going on with an old bridge over the Anacostia River. To his surprise, Harriet Tregoning began to lay out her dream for transforming that old span into a park.

Scott Kratz ’92 was having breakfast with a good friend, who at the time was director of D.C.’s Office of Planning, when he asked an offhand question about all the construction going on with an old bridge over the Anacostia River. To his surprise, Harriet Tregoning began to lay out her dream for transforming that old span into a park.

“You want to help?,” she asked.

That was six years ago. Kratz, a history major in his Pomona days, eventually quit his job at D.C.’s National Building Museum to lead an effort that now employs nine full-time staffers and has set a $139 million goal that includes bricks and mortar as well as investments in nearby neighborhoods to ensure local residents can thrive in place by the time it opens in 2023.

Along with lots of good press, the project has drawn financial backing from the city, foundations and corporations as well, with Building Bridges Across the River, (a nonprofit where Kratz is vice president), so far securing $85 million of the needed funding while engaging the community in a positive vision for the future.

Ambitions for the 11th Street Bridge Project were big from the start. Take an abandoned bridge connecting the well-off Capitol Hill and Navy Yard neighborhoods to low-income and often overlooked Anacostia. Turn it into a vibrant park devoted to recreation, environmental education and the arts. And, in some way, help bring the city together.

Plans soon grew even more ambitious. During one of the 1,000 community meetings held to date, one thing became clear: there were much greater needs in Anacostia—for wealth creation, housing, jobs and more. The effort shifted toward the concept of equitable development, with the aim of getting ahead of gentrification and potential displacement. The key question: “Who is this for?” asks Kratz, noting the massive disparity in household incomes between the mostly white area west of the river and mostly black Anacostia to the east.

Some of the answers: launch workforce development efforts to help people get jobs in fields such as construction, start a homebuyers club and a community land trust, a mechanism that allows people with limited incomes to become homeowners. (Simply put, buyers purchase the house, but the trust owns the land beneath it, which reduces the price. Deed restrictions limit buyers to those within a certain level of income.) Already, 71 renters have become homeowners. Long-term plans call for 1,000 units of affordable housing. Kratz recently piloted 5-to-1 matched savings accounts for 110 east-of-the-river families to support access to college.

Of course, economic justice isn’t the only aim of the project. Everything from urban agriculture to an environmental education center to public art and performance space are part of the plan.

This may sound like a lot for one span to hold, but for Kratz it’s not so much about the bridge as the communities it will connect. Kratz notes how D.C. is booming, with a growing population, but areas such as Anacostia have been left behind.

“It’s really tempting to think, ‘This isn’t our job,’” says Kratz. But “if we don’t get this right, then we’re probably not going to get it right in this city.”

—Mark Kendall

AP Photo/Aaron Gash

Milwaukee Bucks Head Coach Mike Budenholzer ’92 was already the talk of the NBA before his selection in April by a vote of his fellow NBA coaches to receive their Coach of the Year award for 2019.

“In less than a year since taking over as head coach,” Matt Velazquez in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel wrote the day the award was announced, “Budenholzer has totally transformed the Bucks. They went from being one of the worst defensive teams to the best in the NBA. They rebound at a high level, they don’t foul and they punish opponents with a potent offensive attack built on points in the paint and letting three-pointers fly. After years of up-and-down play, the Bucks were consistent on their way to recording the best record in the league this season. They lost two games in a row just one time and won the season series against every Eastern Conference foe. Budenholzer’s schemes, love of efficiency in all aspects of life and individual development— known as ‘vitamins’— are hallmarks of his philosophy that have paid dividends since the day he arrived in Milwaukee last spring.”

In his first year with the Bucks, Budenholzer guided his team to a league-best record of 60-22 and the top seed in the playoffs. The last time Milwaukee had 60 regular season wins was almost 40 years ago, in 1980–81, the era of Marques Johnson, Bob Lanier and Sidney Moncrief. This year’s record was a 16-victory improvement over last season and gave the Bucks their first divisional title since 2000–01. The Bucks were the only team to rank in the top four in both offensive and defensive ratings, and had the best net rating in the NBA.

Still described occasionally as a “disciple” or “acolyte” of the legendary Coach Pop—Gregg Popovich of the San Antonio Spurs (and previously the Pomona-Pitzer Sagehens)—under whom he served as assistant coach for almost two decades before getting his first head coaching opportunity with the Atlanta Spurs, today Budenholzer has earned his own three-letter nickname—“Bud”—and has emerged as a coaching force in his own right, though he still attributes much of his success to learning at the feet of the master.

Of course, all he did in Atlanta was lead the Hawks to four playoffs and record the team’s first 60-win season while being named 2015 Coach of the Year. Last year, however, with the Hawks in a rebuilding mode, Budenholzer decided that the time was right to move on—and the offer from the Bucks was the perfect next step.

As with Coach Pop, Budenholzer brings to the team not only a deep understanding of the game, but also a host of intangibles that sports writers struggle to describe. Take, for instance, his reputation for making strange faces in the heat of the moment.

“Though friendly with the media, Budenholzer has long eschewed the spotlight, as Pop always taught his staff to do,” reports Chris Ballard ’95 in Sports Illustrated. “Fairly or not, what Bud may be best known for—outside his coaching—are his facial expressions. The cameras started picking them up in San Antonio. His greatest hits include: Disappointed Dad; Dude-Cut-Me-Off-on-the-Merge; Man-Trying-to-Decipher-Legal-Document; and Just-Watched-a-Bull-Gore-Someone. Observers delight in captioning them on Twitter. An example, from Rob Perez of the Action Network: ‘I swear every time Mike Budenholzer is on camera he looks like he just watched the stampede scene from The Lion King.’”

At the same time, however, that naked authenticity seems to be one of the keys to his success as a coach. Ballard quotes Utah Jazz guard Kyle Korver, who played for Budenholzer in Atlanta: “One of the best parts about playing for him is watching him in the film sessions. But that’s how his heart feels, man! He cares so much and he’s just so disgusted with what’s going on in the court, but it’s so genuine. He’s just someone you want to follow because he’s not just a good person, but he’s great at his craft.”

Personally, Budenholzer had previously expressed his hope that the Coach of the Year award this year would go to his former assistant, Kenny Atkinson, for the job he’s done as head coach of the Brooklyn Nets.

“It is an incredible honor to be recognized by your peers, and that makes this award truly special,” Budenholzer said after the award was announced. “Thank you to my colleagues across the NBA, and most importantly thank you to our players and staff in Milwaukee. The players’ and staffs’ work this year has given our team and our fans a very special season.”

—Mark Wood

WANTED Lead Camera and Lights for a documentary-style film.”

WANTED Lead Camera and Lights for a documentary-style film.”

“Congrats to Maximilian Zarou (PO ’99) on his upcoming TV appearance!”

“If anyone has a short or feature film they’d like to get into a festival, PM me.”

With nearly 2,000 members, the Claremont Entertainment & Media networking group’s Facebook page is a lively community of alumni of The Claremont Colleges who mostly either work in Hollywood or aspire to.

Founded in 2007 by a group that included actor Kelly Perine ’91, the network offers a clearinghouse for job openings, freelance gigs, congratulations and queries from alumni and current students of the seven Claremont campuses.

“I was on the ground floor of getting this puppy up and running, and after 10 years we’re on the brink of turning The Claremont Colleges into forces to be reckoned with, just like other universities that seem to have a stronghold on Tinseltown,” says Perine, who is currently appearing in Nickelodeon’s Knight Squad.

The Claremont Colleges have some Hollywood heavyweights in their corner, including Interstellar producer Lynda Obst ’72 and The Martian producer Aditya Sood ’97, who is also a Pomona trustee.

“What they’re doing is fantastic,” Sood says of the group, also known as CEM.

Before the last decade or so, students and alumni often discovered Claremont entertainment industry contacts either by digging hard or by accident, which is how Sood met his first show business contact, Greg McKnight ’90, now a partner at United Talent Agency. “I was a sophomore sitting in Honnold reading weekly Variety, the print paper,” Sood remembers. “All of a sudden this guy came up to me and said, ‘Oh, how long have they had that here?’ And I said, ‘Ever since I’ve been a student.’ And he said, ‘When I was a student here, I used to write letters to get [the library] to subscribe.’ Then he said, ‘Do you want to get lunch?’ and we did. We became really good friends and have crossed paths many, many times in business over the years.”

At the offices of Lynda Obst Productions on the Sony Pictures studio lot in Culver City, Obst’s right-hand woman is Katarina Hicks ’10, who reached out to Obst because of their Pomona connection and was hired as Obst’s creative executive. She since has been promoted to development executive. There are “tons of people my age in the ‘trenches’ making moves up the ladder,” says Hicks.

Obst proudly notes that one of her former Pomona interns, Justin Huang ’09, is now the head of development at Pearl Studio, the Shanghai-based animation studio formerly known as Oriental DreamWorks. Obst says the CEM group has grown “very strong,” and she continues to speak on the Claremont campuses and offer guidance to students and recent graduates.

“I have always responded to anyone from Pomona, and they’ve come to my office, and I’ve given them advice—but not when I’m in production,” Obst says. “Also, they’ve tended to be my smartest interns, because you know when you get a Pomona person, they can write English sentences; they can analyze scripts; they can speak well; they can think on their feet. I mean there’s just been a very consistently high quality.”

It is a competitive field, and a shared alma mater isn’t enough on its own. But Sood emphasizes the value of the preparation students receive at the 5Cs, as the Claremont undergraduate schools are known. “There’s a real literary component to what we do,” he says. “You’re reading books; you’re analyzing material; you have to have critical thinking and a lot of problem-solving in novel situations. I really think the liberal arts background is a perfect steppingstone for this kind of work.

“The advice I give every time I talk to students is something I didn’t really have but I think would have been great to have: Try to find the other people on campus who also want to do this, and get to know them now. Get to know them as students, because they will form the nucleus of your network that will last you throughout your entire career.”

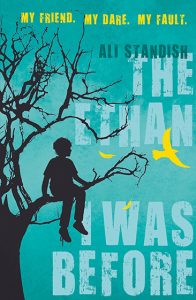

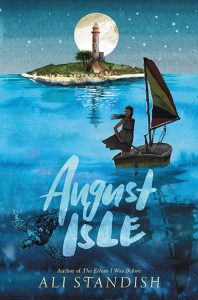

A storyteller from childhood and now an all-grown-up author, Ali Standish ’10 is writing children’s and middle-grade books that are being noticed by children and critics alike.

A storyteller from childhood and now an all-grown-up author, Ali Standish ’10 is writing children’s and middle-grade books that are being noticed by children and critics alike.

Her first book, The Ethan I Was Before, received a coveted starred review from Publishers Weekly: “Readers will be riveted.” Her debut was an award-winner, racking up accolades like the Children’s Book Review Best Book of the Year and the North Carolina Young People’s Literature Award, and landed on a slew of long-lists, including being named a Carnegie Medal Longlist Title.

August Isle, Standish’s second book published by HarperCollins, was released in April and is a work with themes of secrets and lies. A Junior Library Guild Selection, it was praised by Kirkus Reviews as “a beautifully written story. An emotional journey of family, friendship, loss, and healing.”

Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham talked to Standish about inspiration, imagination, what’s an absolute must in children’s literature and more.

Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham talked to Standish about inspiration, imagination, what’s an absolute must in children’s literature and more.

PCM: So, why writing? What led you down this path?

Standish: You know, it’s hard to say that I chose writing. This sounds very cliché, but I think writing more so chose me, or at least storytelling did. A lot of my earliest memories are of making up stories about things. And from when I was really little, my mom and I would play storytelling games. So it’s always been something that I needed to do as a creative outlet. I wrote my first manuscript when I was in the sixth grade and have been writing ever since. When I was at Pomona, I was fortunate to be able to take some creative writing classes with [poet and former Pomona College Professor of English] Claudia Rankine, and it was wonderful. I also was able to do creative writing as part of my study-abroad curriculum in Cambridge.

I’ve just been doing it for really as long as I can remember. Then one of my really good friends, an important person in my life, passed away in fall of my senior year. And a big part of coping with that for me was writing my first children’s lit manuscript. I wrote a manuscript that was a very boilerplate, poorly written fantasy novel. And I was able to submit that as my final project for Children’s Literature 101. So senior year was when I really edged over into writing children’s literature.

I’ve just been doing it for really as long as I can remember. Then one of my really good friends, an important person in my life, passed away in fall of my senior year. And a big part of coping with that for me was writing my first children’s lit manuscript. I wrote a manuscript that was a very boilerplate, poorly written fantasy novel. And I was able to submit that as my final project for Children’s Literature 101. So senior year was when I really edged over into writing children’s literature.

PCM: Talk about why you moved into children’s literature.

Standish: Astrid Lindgren, who is the author of the Pippi Longstocking series, has this great quote about how she only wants to write for children because children are the only ones who can perform miracles when they read. That quote really resonates with me because I just have such powerful memories of being a reader as a child. And what a sacred experience that was for me and a formative experience. To be a part of creating that for another generation of children, I think, is probably the most rewarding thing that I can imagine doing.

PCM: Where do you get your ideas from?

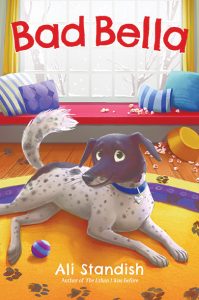

Standish: I think every book that I’ve written so far has started with a kernel from my own life experience. With The Ethan I was Before, that book really started with the grief that I felt after losing the best friend that I mentioned earlier. With August Isle, it started with a trip to Indiana for a family funeral where I was reminded of a family secret that stoked some curiosity for me, and that I thought could potentially make a good book. Then with Bad Bella, that book is actually based on my own dog, Bella. The one I have coming out in the winter, called How to Disappear Completely, is actually about a girl who gets vitiligo, which is a condition that my husband was diagnosed with a couple of years ago.

It always starts with something from my life experience. Then it becomes a process of finding enough other inspiration in the world around me to take that seed of truth and turn it into a story that is not my story, that is something new and exciting. I was just working on my launch-party speech for August Isle, and I was comparing it to being a kid hunting for Easter eggs. It’s always that hunt of keeping your eyes out wherever you go and waiting for those interesting people to cross your path, or a news article that has something in it that you are drawn to.

And then once you have those different kinds of sources of inspiration, it’s pulling them together and trying to find the connections between them. Because I think how you make the connections between the different elements of your story is how you make your story unique. There’s no subject that hasn’t been written about; it’s how you write about it and what you connect it to that makes it interesting. So that’s the part of the process that really is my favorite part, that gets my neurons really firing—thinking about how to bring things together in a new way.

PCM: How do you feed your imagination? You’re looking for new ways of telling things. What do you do to stoke that fire?

Standish: I read—that’s the main thing. And then I have an overactive imagination. The positive manifestation of that is that I am quite easily able to take someone passing me on the street and create a story around them. The downside is that I have a lot of anxiety in things, and I think that is also a product of imagining different scenarios. Let’s see. I travel whenever I can. That is really helpful. In August Isle, there’s a character who is an old and wizened seafarer who has just come back from a long journey around the world. Being able to rely on what I’ve learned from being in different places is really helpful in that, and it’s cool to be able to introduce those places and different concepts to young readers.

PCM: What’s your favorite book or books from your childhood?

Standish: The two that I always go back to are Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis. I read both of those books in fifth grade, which was a really transformative and transitional year for me. They are interesting counterparts to one another because they’re both about children who find magic worlds. And in one they stumble into Narnia. But in Bridge to Terabithia they create that world for themselves. That idea really intrigued me. I lived in kind of a rural place that had a little forest in the backyard, and I just decided that my backyard was going to be my magical kingdom and called it “Nabithia,” because I hadn’t learned a lot about originality at that point. I just took Narnia and Terabithia and stuck them together, and I brought that into our playing make-believe. I kept a diary in the hollow of a tree, where I would write down these different episodes that I created for myself. And that was a really foundational experience for me in learning how far I could stretch my imagination and what I could do with it.

PCM: Nature plays a big role in your writing. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Standish: Yes. I wrote The Ethan I Was Before after my husband and I moved to England. I didn’t know anybody. I had no job prospects. I was very isolated. And I was really homesick and particularly homesick for the American South. So writing the setting for The Ethan I Was Before—writing that town of Pam Knot, Georgia—was a way for me to reconnect with a place that I really missed.

Nature played a huge part in my imaginative journey. And I think we continue to learn about how important nature is in terms of development, in terms of mental health. I was just reading an article in The New York Times yesterday written by Oliver Sacks about the importance of gardens in helping patients that have neurological issues. Unfortunately, because of the way that society has moved, it’s harder and harder for kids to have meaningful interactions with nature on their own. So I think it’s more important that they get that through books. If they’re not getting it anywhere else, at least they can have it on a page.

PCM: Narnia is outdoors. You’ve been inspired by that.

Standish: Yeah. You think about spaces like the Forbidden Forest in Harry Potter and how alluring that is. And even going back to fairy tales, we have a fascination with forests and the secrets that can be found there. Een in an age where children don’t play outside as much, I think that fascination is very much in our DNA.

PCM: Something primal about it.

Standish: Yes, yes. And I also think it’s important for kids to develop a healthy appreciation of our Earth and to know how important it is to safeguard it. This is kind of off-topic, but I think we’re coming to a point where we know that this generation is going to be the one who’s either going to really create change and be able to be the ones who are going to force everybody else to save the planet, or they’re not. I think having that emphasis there and that exposure early on is vitally important.

PCM: What elements do you think a children’s or middle-grade book has to have to tell a story successfully?

Standish: I think the biggest thing is honesty. Kids that age are … they’re coming into themselves. They’re already looking back on their childhood with the sense of nostalgia but also suspicion. Because for most of them, if they’ve had healthy upbringings, they have been isolated and insulated from a lot of the harsher realities of life. And they’re really curious about those things. So my books tend to have heavier subject matter in them. Adults come up to me all the time and say, “Do you really think an eight-year-old or 10-year-old wants to read about this?” And my answer is emphatically, “Yes, they do,” because books are a safe place to learn about those kinds of topics, so what better place to introduce them.

Adventure is always going to be key for middle graders because as much as they may be growing up socially, I think a lot of them are still holding on to that quest kind of structure that they have probably read in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and Harry Potter and books like that. So I always try to mix issues that can be hard to talk about with a sense of adventure and humor and sometimes a little bit of magic that helps to lighten up that heavier stuff.

PCM: Kids can deal with more than we give them credit for.

Standish: Exactly. And, you know, they do with the internet and social media, the way they are; they’re always dealing with more than we know that they are.

PCM: How do you think your Pomona education contributed to your taking this literary path?

Standish: Pomona gave me everything that I needed to be able to take this path. Part of it was just being around so many people who were passionate about whatever it was they were doing. Even if it was something that didn’t seem like it could translate easily into a lucrative career path. And people who were unashamed about what they were passionate about. That made me feel like it was a safe place to explore my passions and to not put myself down for having an idea that I might one day be able to write professionally. I got a lot of encouragement from the faculty there in terms of my writing. I also got an occasional kick in the pants that I really needed.

My advisor was [Professor] Toni Clark, who passed away a couple of years ago. I will never forget the first class I took with her; I wrote an essay on Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, where I looked at bird imagery. I typed it up and sent it off to her, and she gave me a C-minus. I was devastated and horrified. That was early on in my career at Pomona. I had a sense that it was confirming everything that my impostor syndrome had told me about—not being worthy of a Pomona education.

When I went in to see her to ask her what I could do better and to plead the case for extra credit, she told me that she had given me that grade because she knew from my contributions in class that I could do much better. And if I were another student, she might have given me a different grade, but she knew that I had it in me to do more and she wanted to pull that out of me. I am so thankful that she did that, because even though it was just a little paper and a small moment, it really made the difference in how I—I’m about to cry about it—it really made a difference in how I saw myself and my potential. That was a message that I didn’t get a lot in high school. Pomona gave me a lot of emotional and intellectual tools to be able to pursue this career path.

PCM: It’s touching to have someone see more in you than you see in yourself.

Standish: Exactly. And for a girl who came from Greensboro, North Carolina, to Pomona—my guidance counselor cried when I told her I got into Pomona. She said, “I don’t believe it.” So, when I came, I really was not sure if it was something that I could handle or a place that I belong. So especially for me to have that reassurance was really powerful.

PCM: What are you reading right now?

Standish: I am reading … nothing that’s going to look good, in fact. I would love to say I’m reading Tall Story. But no, I am reading an audio book by an Australian author I love called Liane Moriarty. She did Big Little Lies, which got turned into that HBO series. And then I’m reading a British mystery.

But I will say that’s not my usual fare. Usually my bedside table is stacked high with 10, 12-odd children’s books that I’m reading.

PCM: Do you alternate between children’s books and adult books? Or do you have a method of how you choose your books?

Standish: I try to. It’s important for me to see what’s out there in children’s books. Every time I open a book, I treat it as a learning experience. I always feel like I come away having learned something new about the craft of writing, whether it’s what to do or what not to do. Then when I need a break from children’s books, generally I tend toward hedonistic pleasures in the adult books. I go straight for the mysteries and The New York Times bestsellers.

PCM: Great. No shame in that.

Standish: Yeah, thank you.

PCM: No, no.

Standish: The English major in me does die a little inside.

While Avis Hinkson was growing up in a Barbadian immigrant household in Brooklyn, she imagined a career in health care. Instead, her life’s work has been guiding college students, first as an admission officer, later as a director of advising and now as Pomona College’s dean of students. “I didn’t go to college thinking I would stay in college,” she says with a laugh. She tells students that “as a college student, you want to chart a career path, and I encourage you to do that. But I also encourage you to be open to the right and left turns that sometimes take place, because they can lead you to wonderful career spots that you couldn’t have possibly imagined.”

While Avis Hinkson was growing up in a Barbadian immigrant household in Brooklyn, she imagined a career in health care. Instead, her life’s work has been guiding college students, first as an admission officer, later as a director of advising and now as Pomona College’s dean of students. “I didn’t go to college thinking I would stay in college,” she says with a laugh. She tells students that “as a college student, you want to chart a career path, and I encourage you to do that. But I also encourage you to be open to the right and left turns that sometimes take place, because they can lead you to wonderful career spots that you couldn’t have possibly imagined.”

Absorb the lesson while growing up in a culturally rich neighborhood that education is the path to a better life. Watch your mother, a seamstress, graduate from college in her 50s after going to work as a teacher assistant.

Absorb the lesson while growing up in a culturally rich neighborhood that education is the path to a better life. Watch your mother, a seamstress, graduate from college in her 50s after going to work as a teacher assistant.

Go along with a high school friend to meet a recruiter from Barnard College. Be impressed that the recruiter is African American, and with the help of financial aid (Barnard costs more than your father makes in a year’s work as a mason), become one of about 25 Black students in a class of 500.

Go along with a high school friend to meet a recruiter from Barnard College. Be impressed that the recruiter is African American, and with the help of financial aid (Barnard costs more than your father makes in a year’s work as a mason), become one of about 25 Black students in a class of 500.

Bump into Barnard student Vernā Myers on your way to the career center to pick a work-study job as a first-year student. Heed the advice of the future Netflix vice president when she suggests a job in the admissions office. Create Barnard’s first overnight-visit program for prospective students of color.

Bump into Barnard student Vernā Myers on your way to the career center to pick a work-study job as a first-year student. Heed the advice of the future Netflix vice president when she suggests a job in the admissions office. Create Barnard’s first overnight-visit program for prospective students of color.

Listen to Barnard senior Marcia Sells (a future dean of students at Harvard Law School) when she encourages you to run for the student seat on the Board of Trustees. Take part in the decision that Barnard will remain a women’s college instead of merging with Columbia.

Listen to Barnard senior Marcia Sells (a future dean of students at Harvard Law School) when she encourages you to run for the student seat on the Board of Trustees. Take part in the decision that Barnard will remain a women’s college instead of merging with Columbia.

After graduation, become an admissions counselor at Bowdoin, establishing minority recruitment programs there. Decide on a career in higher ed instead of health care, later earning an M.A. in student personnel administration from Columbia University’s Teachers College and an Ed.D. from Penn.

After graduation, become an admissions counselor at Bowdoin, establishing minority recruitment programs there. Decide on a career in higher ed instead of health care, later earning an M.A. in student personnel administration from Columbia University’s Teachers College and an Ed.D. from Penn.

Establish minority recruitment programs at Cornell before coming to Pomona in 1990 as associate dean of admissions. Contribute to Pomona’s minority recruitment plan before moving on to become director of minority recruitment at the University of Southern California.

Establish minority recruitment programs at Cornell before coming to Pomona in 1990 as associate dean of admissions. Contribute to Pomona’s minority recruitment plan before moving on to become director of minority recruitment at the University of Southern California.

As director of advising for more than 18,000 undergraduates in the College of Letters and Sciences of the University of California, Berkeley, get an eye-opening look at the bureaucracy of a large public university. While furloughed amid a California budget crisis, remember the allure of small liberal arts colleges.

As director of advising for more than 18,000 undergraduates in the College of Letters and Sciences of the University of California, Berkeley, get an eye-opening look at the bureaucracy of a large public university. While furloughed amid a California budget crisis, remember the allure of small liberal arts colleges.

Go home again and call your 96-year-old father to tell him you’ve been named as Barnard’s first African American dean of the college. Feel grateful that a man who felt most comfortable talking with the public safety officers and janitors when visiting campus lived to see it.

Go home again and call your 96-year-old father to tell him you’ve been named as Barnard’s first African American dean of the college. Feel grateful that a man who felt most comfortable talking with the public safety officers and janitors when visiting campus lived to see it.

Go home again (again). Leave behind your newly renovated childhood home in Brooklyn and return to Pomona as you are drawn back to the campus where G. Gabrielle Starr has recently become Pomona’s 10th president, the first woman and first African American to lead the campus.

Go home again (again). Leave behind your newly renovated childhood home in Brooklyn and return to Pomona as you are drawn back to the campus where G. Gabrielle Starr has recently become Pomona’s 10th president, the first woman and first African American to lead the campus.

Discover that April Mayes ’94 is now a professor of history at Pomona, and Nate Kirtman III ’92 is on the Board of Trustees. (Both were student workers in admissions when you worked at the College before.) Know that the seeds you planted have helped make Pomona one of the most diverse private residential liberal arts colleges in the country.

Discover that April Mayes ’94 is now a professor of history at Pomona, and Nate Kirtman III ’92 is on the Board of Trustees. (Both were student workers in admissions when you worked at the College before.) Know that the seeds you planted have helped make Pomona one of the most diverse private residential liberal arts colleges in the country.