Professor Kyla Wazana Tompkins, a 2023 James Beard Media Award winner, holding a Strawberry Fluffy Matcha at Tea Maru in Arcadia, California. Photo by Jeff Hing

On Boba

Gelatinousness in the Bones

Originally published by the Los Angeles Review of Books in the April 2022 issue of LARB Quarterly and reproduced below with permission.

My first encounter with boba was not my first encounter with the gelatinous food objects that have come to occupy my imagination for so many years since. But because it took place my very first week in the United States in 1998, boba drinks, which are actually Taiwanese, have come to be associated for me almost entirely with California.

Gelatinousness was in my bones long before I moved from Toronto to California, a state in which crispness is a sanctified culinary value. By contrast, I grew up with collagen-rich food that often included ingredients like cow feet and tongue and other usually discarded bones and body parts. I met boba that first week in the U.S.—still reeling from the shock of moving from East Coast to West Coast; of encountering a culture so car-centered you couldn’t even walk across a road to get groceries; of suddenly walking through the TV screen called the 49th parallel and finding myself in a Truman Show–esque landscape of U.S. flags on every corner—when my assigned grad housing roommate, a fellow international student from Taiwan named Wen-pei (“call me Wendy”), got a friend of hers to drive us to a local boba shop so that I could try something she associated with home.

I remember the drive to get there through the suburban eternal of small-town California; I remember the white and blue and pink of the store; I remember feeling relief at finding myself in a store full of not-white people. I distinctly recall the tannic pucker of black tea syrup on the tongue, how concentrated black tea makes your taste buds feel concave and how the sweetness and milk bring them back. And I remember the chewy spheres and how I took to them immediately.

I guess there are people who don’t like boba or tapioca or any food that resists the tooth. I guess there are people who don’t want to eat cow’s foot. I am not one of those people. Boba for me, then and now, tastes like a kind welcome from a new friend to a strange country, even when that new friend is a stranger, too.

If I were to name my country now, almost a quarter-century of emigration later, it would still not be the United States; but it would definitely be Los Angeles. I have come to love L.A. with the fullest of hearts. My Los Angeles is, like everyone else’s, severely circumscribed by My Commute, the topic of constant conversation here. This is another way of saying that my L.A. is circumscribed by how the limits of time have shaped how far I can drive on a given day and still attend to the basics of getting things done: working; being with my son; writing; domestic labor. And thus, my L.A. is not the cinematic L.A. of the West Side and Beverly Hills. It is not even the consciously unglamorous new money of Downtown L.A. with its lofts and weekend scene, nor is it the studiously louche energy of the Silver Lake creative class with their elaborate artisanal take on everything that should only cost $3.

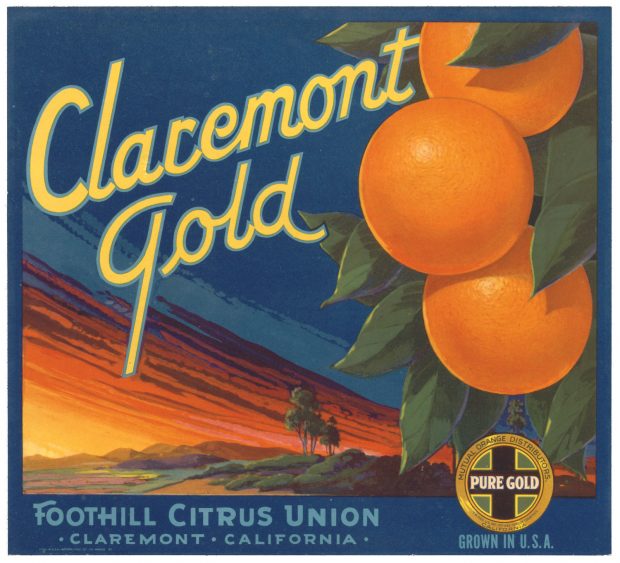

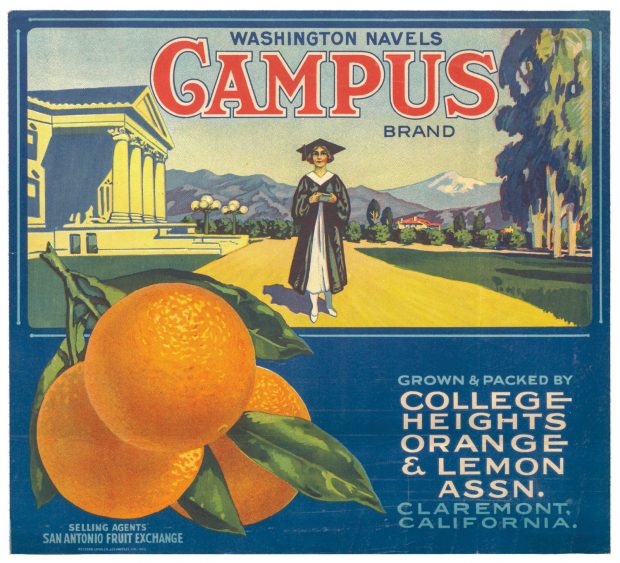

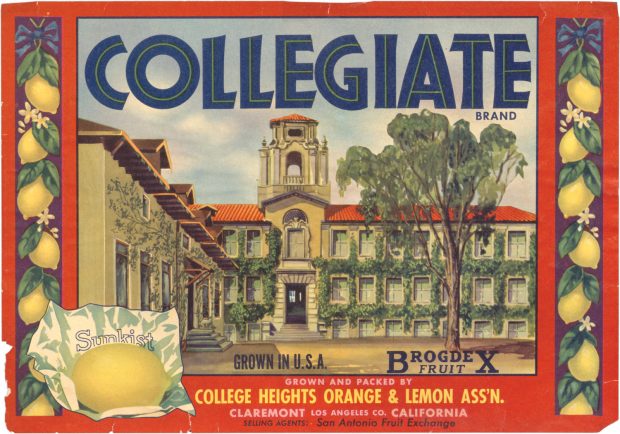

Largely, my L.A. is everything to the north and south of the 210 artery that runs between the Inland Empire, where I work, and Altadena, where I live. All along my commute, lying to the south of me in the huge space of land between the east-west rush of the unlovely 10 freeway and the brown and frowning imposition of the San Gabriel Mountains that lie on the north side of the 210, is the great gift that is the multiethnic and transnational checkerboard of neighborhoods called the San Gabriel Valley. Much has been spoken and written by people who think about eating a lot, including David Chang and the late Jonathan Gold, both of whom recognized the SGV (“the Ess-Gee-Vee”) as the center of the widest range of and the very best multiethnic Asian restaurants in the United States. Part of what defines the SGV is that you take freeways to get there but the freeways don’t really take you there; instead, you take an off-ramp and then drive actual streets to get to actually anywhere, a long romp through a lot of space to get to a singular place. This, I think, keeps the SGV less shiny than other parts of L.A. but more human and more complex: You have to either work to get there or you have to be from there to enjoy finding yourself there.

Another way to say this is that the best parts of L.A. are those areas where other immigrants do their living: the arid and dried-out streets with not enough trees on them; the parched stucco of the ordinary bungalow; nearly identical strip malls that seem to repeat themselves block after block after block until you’ve lived here for at least half a decade and your vision sharpens to the differences between them. Also the not-choice real estate that you find along highway frontage lanes in which the greatest enemy of your sleep isn’t the aquatic swoosh of freeway sounds but the hideous roar of police helicopters chasing down cars for reasons you never can find out.

Boba drinks were born in Taipei, either at the Chun Shui Tang Teahouse in Taichung or at the Hanlin Tea Room, both of them in Taiwan. Since the 1990s, boba, a tiny bubble of refined and boiled cassava paste that sits at the bottom of a sweet and fairly complex drink, has become one of the most globally recognized food and drink commodities of Asian origin. Its stores are gathering places for youth of all demographics, but particularly, the studies tell us, of Asian teens from multiple transnational diasporas.

Cassava has a long and interesting history as a global commodity that, like most modern commodities, found its first foothold in the circulations of modern capital that emerged out of the Western colonial project. Cassava, food historians tell us, is indigenous to Brazil but was exported around the world, first to feed enslaved Africans as they were transported to the ships that stole their lives to the Americas.

Food anthropologist Kaori O’Connor tells us that what we know as tapioca (originally a Tupi food), boba, or cassava was originally known as manioc. Poisonous in its root form, in order to be eaten manioc requires days of soaking and fermentation to extract the possibly lethal amounts of hydrocyanic acid from its fibers. After a long soak, manioc is then vigorously pounded or grated to produce the meal and then flour now known in Portuguese as farinha. In precolonial times, what the West would now recognize as tapioca was then made from the liquid left behind when farinha was extracted. Between the cultivation and consumption of manioc, including drinking fermented tapioca drinks and hunting animals, the preinvasion Tupi diet was well organized to supply enough carbohydrates and meat for survival.

Boba drinks, sometimes called bubble teas, are creative concoctions that might include tea, milk, fruit juice, sugar and other flavors—and of course, the smooth pearls of tapioca known as boba.

Deracinated from Tupi culture and exported abroad as the European invasion and markets expanded, cassava became a central provision provided by enslavers to enslaved peoples: Though labor intensive to produce, it also provided carbohydrate calories to fuel cruel amounts of labor and energy extraction and was flavorless enough to adapt to multiple cuisines and locations. Cassava was transported to inland Africa to feed enslaved peoples as they were stolen and put on forced march to the vessels that would sever them from their worlds. It was taken to the sugar colonies to provide plantation and plot provisions. Cassava was, in other words, one of the most important sources of caloric fuel for the colonial world.

Processed cassava is smooth, chewy and soothing. Its neutral flavor allows it to live peacefully alongside almost any flavor continuum from spicy to herbaceous; its gelatinous quality makes it a splendid preservative. Mixed with milk, it was used to create English puddings that kept dairy from spoiling; in Jamaica enslaved people reappropriated cassava to invent the divine and irreproachable coconut-milk-soaked fry-bread called bammie.

Cassava finally arrived in Taipei directly from Brazil in the hands of the Portuguese, either in the 17th or 18th centuries, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that boba left Taiwan to become a global drink phenomenon. But is boba necessarily a drink? If you read boba cookbooks or watch videos about how to make boba, you come to understand that it is really just another kind of noodle, albeit one with a particularly resistant visco-elastic bounce in the mouth.

Much has been written about “Q,” the elusive mouthfeel so favored in Taiwanese cuisine, and a lot of that writing circles in wonderment around the idea that a particular mouthfeel could belong to a particular place. We are used to thinking about flavor profiles geographically: It is taken for granted for instance that butter, white wine and lemon are French, that turmeric, cumin and curry leaf might signify a cuisine touched by the Indian Ocean; that ginger, garlic, scallion and soy generally accompany a number of East Asian cuisines across borders.

But those are flavors: Mouthfeel is something else altogether. How does a desire for a particular experience along and against and between the roof of your mouth and the length of your tongue emerge as a cultural phenomenon? I once spent a year in Boston and came away with the sense that, except for steamers and lobster and the impeccable genius that is chowder, basically everything I was eating was unnecessarily fried or topped with mayonnaise; two different kinds of too oily. Growing up Moroccan, I came to believe that we, as a culture, like our food wet and even sticky. Someone who had only eaten couscous in a restaurant wouldn’t know that at home, couscous comes with a small pitcher or bowl of broth to keep it from getting dry. Even our salads are cooked.

What is taste? Over 25 years ago, I attended a food history conference in Fez where I heard the chef, restaurant owner and food scholar Fatéma Hal talk about how Moroccans in general do not eat chocolate, and that it simply isn’t a commodity with a great deal of pull in the country. That insight stunned me: It had never occurred to me that one might belong to a food desire, as one belongs to a nationality.

There is such a thing, then, of a geography of the palate, if we define a palate as a set of flavors, aromas, textures, sounds and memories agreed to be desirable or disgusting. A shared palate develops out of necessity, by force, because of ecologies, as a result of invasion and theft or because communities have been colonized or invaded. It’s not always a bucolic or pretty history, and a short trip through the muck and mess of the past delivers you directly away from your wishes for anything like an “authentic experience.” But palates are always particular. And they feel particular: They feel like they belong to the us-ness of us, the me-ness of me, the here-ness of wherever you came from.

Palates live in the mouth, but they can also travel. Palates change.

If cassava is a global commodity that illuminates Asian and hemispheric American commodity chains and leisure cultures in the form of the boba tea joint, linking dispersed colonial history and late-modern national projects to each other, so too do the coffee, tea and sugar ingredients that make up the drinks. These energy sources shape the sensory everyday into which our bodies are plugged and fuel the jagged experience of working under capital.

Boba drinks, especially when made with tea or coffee, feed the body’s particular caffeine/sugar/carbohydrate addictions that plug us into work and study schedules, but its pleasures are leisurely, too. Boba can roll out in phases, and in the more artisanal of boba drinks there is no mouthful that has not been designed with mouthfeel in mind, every layer an event: the chewiness of the balls at the bottom of the drink; the crystalline coolness of an ube slush, the meringue density of cream cheese topping. Are there any boba drinkers that mix the layers together? I’ve never seen that and it seems almost taboo: Boba drinks seem to assume a palate that wants to be entertained, every layer a different texture game. Boba, in short, is fun: a ball pit at the bottom of a cup that is eminently photographable, improved by any Instagram filter, an invitation to restage childhood games in your mouth.

The resistant gelatinousness of boba, the elusive “Q” texture, has variously been described as “springy and chewy” or, as one writer translated from the words tan ya—“rebound teeth.” Gelatins are solid liquids, substances that are able to bind water, thickening and holding their shape, and, interestingly, often suspending aroma and taste for a slow release such that the experience of flavor unrolls slowly in the mouth and nose. The best gelatins—which is to say the smoothest and the clearest gels—promise an evanescent physics of recoil and release: scientific food at its best, where it meets the quotidian productions of street and small shop food production, transcribed into a multisensory event.

If I could write this essay as a letter to other lovers of the gelatinous, I would extol the pleasures of these drinks as they happen in slow motion time. Some boba drinks contain multiple jellies: boba followed by basil seeds followed by lychee or grass jelly, followed by a fruit drink or a tea. Some bobas at the slushy end of the drink menu are layered with flavors like ube and coconut milk. Driving around the SGV with my son during the pandemic, trying to get away from the hygienic pandemic containment field defined by masks and car windows and windows and doors and fences, we drove to Rosemead to Neighbors Tea House to try the smashed avocado and durian drinks as well as the mung bean drinks, none of which we had with boba but which seemed boba-aligned in their indifference to any cultural line between drink and food.

We tried The Alley’s Snow Strawberry Lulu and Brown Sugar Deerioca as well as the exquisite snow velvet muscat black tea, each of them a meditation on the kind of symphonic experience that sweetness can make musical. At the Boba Guys, we tried the perfect candy drink banana milk, the smoky black sugar hojicha, and their highly photogenic strawberry matcha latte and strawberry rice milk drinks. We tried the peach tea and the strawberry fruit teas at Dragon Boba in La Cañada, and ogled but did not try the boba doughnuts. By far some of the best boba we had was the housemade boba at Tea Maru in Arcadia, where we tried the Strawberry Fluffy Matcha, layered atop a berry jam bottom, and the brilliant Okinawa Slush that flips the whole paradigm and puts their homemade brown sugar boba on the top of the drink.

Boba’s pleasing categorical and sensory promiscuity is summed up in the boba shop’s ubiquitous wide straw, so completely opposite to the anemic straws of Western fast food. The former are made to not just let a liquid through but actually to let in food-like drink. This confusion of eating categories is perhaps what some people can’t take about boba drink culture: If Claude Lévi-Strauss long ago proposed a culinary triangle that elevated the West from the Rest via a differentiation between the primitive Raw and the cultured Cooked, Western food cultures tend to assume the difference between food and beverages, with the exception of the historically virtuous smoothie. Boba drinks are food and drink, or along another line, drinks that are more complex than a quick sip that slides down the throat. Boba tea from a really quality boba shop insists on a complex and interesting sensory experience that is visual as well as flavorful, that choreographs layers of texture that are as casually beautiful as they are sensually complex.

How does one find a resting place in a culture that is not one’s own? Is there a way to approach a world of difference without stealing from it? There are many bad racial subjects in food culture, just as there are in the world: the appropriators, the people who lift ingredients and transport them to other foods without understanding or appreciation for local food technologies; the cosmopolitans, so eager to recite facts and knowledge about food cultures not their own; the thieves who take recipes from their original knowledge holders and reproduce them deracinated and unrecognizable. And in turn there are the “good” racial subjects, who write only about their own lineages and cultures. The immigrants nostalgic for a taste and feel of home, banking on recreating their memories as closely as they can approximate.

One shorthand way to talk about the politics of difference in food has been through bell hooks’s cannily marketable phrase “Eating the Other,” in which usually white consumers devour exotic difference metaphorically and figuratively, while not paying attention to the people whose lives and complexity they commodify. These are the slings and arrows thrown so easily around social media debates on race and difference and eating, and some of them land where they should, and it is all so very tiring. We are in a tiring time.

A more generous and gentle take might be that there are places and histories where people and their desires cross each other—where touch happens, where the sensory congruences that shape each of our innermost senses of having private desires and tastes in fact overlaps and resonates, as history or as a shared present. It is harder work to get there: History is dense and chewy that way.

Have a meeting to run? When Zoom gets tiresome or you’re trying to build a team online, finding a way to connect the people in the boxes is important.

Have a meeting to run? When Zoom gets tiresome or you’re trying to build a team online, finding a way to connect the people in the boxes is important. Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsessions

Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsessions Frost Fair Dance

Frost Fair Dance Best Practices in Educational Therapy

Best Practices in Educational Therapy Doing Supportive Psychotherapy

Doing Supportive Psychotherapy One Small Sun

One Small Sun The Road Through San Judas

The Road Through San Judas Can’t Stop Falling: A Caregiver’s Love Story

Can’t Stop Falling: A Caregiver’s Love Story Forty Years a Forester

Forty Years a Forester

Try not to drool when you read the menu that won Pomona College chefs Amanda Castillo, John Hames, Marvin Love and Angel Villa a silver medal in a recent national cooking competition.

Try not to drool when you read the menu that won Pomona College chefs Amanda Castillo, John Hames, Marvin Love and Angel Villa a silver medal in a recent national cooking competition.