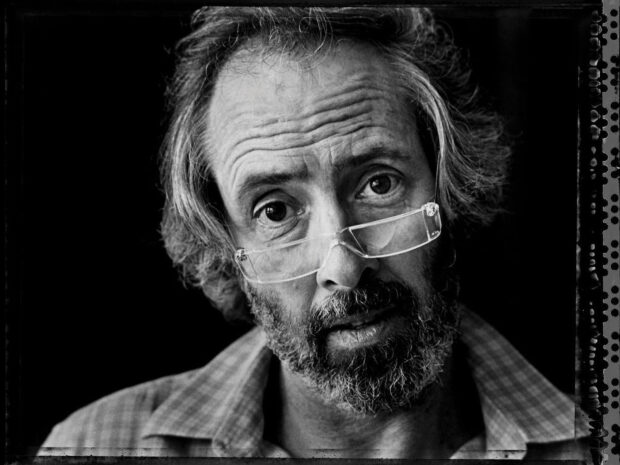

Academy Award-winning screenwriter, Robert Towne, poses during a 1981 Los Angeles, California, photo portrait session. Towne won the Academy Award for his “Chinatown” original screenplay.

Screenwriter Robert Towne ’56, who won an Academy Award for best original screenplay for the classic film Chinatown, died July 1, 2024. He was 89.

The 1974 movie starring Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway was nominated for 11 Oscars but won only one, for Towne’s script about corruption and murder set in 1930s Los Angeles amid the city’s longstanding water wars.

Towne earned three other Academy Award nominations during his career, for The Last Detail (1973), again starring Nicholson; Shampoo (1975), starring Warren Beatty; and Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984), though he disliked the Tarzan movie so much he asked to be listed in the credits by the name of his dog. The official listing of nominees still bears the pup’s name: P.H. Vazak.

Fifty years after it was made, Chinatown remains a standard on lists of greatest films and screenplays and often is studied in film schools. The script was influenced by black-and-white photographs meant to depict novelist Raymond Chandler’s 1930s L.A. and also by the chapter on water in Southern California Country: An Island on the Land by Carey McWilliams—coincidentally the grandfather of current Pomona College Professor of Politics Susan McWilliams Barndt.

Though Towne also went on to direct four movies, Personal Best (1982), Tequila Sunrise (1988), Without Limits (1998) and Ask the Dust (2006), he was better known in Hollywood for his work as “a script doctor,” with uncredited work on The Godfather, among many other films. Mario Puzo, who shared the Oscar for adapted screenplay for The Godfather with Francis Ford Coppola, thanked Towne in his acceptance speech for writing the garden scene between Marlon Brando and Al Pacino. Notably, Towne also is said to have received uncredited assistance on Chinatown from a Pomona College roommate, Edward M. Taylor ’56. Taylor, Pomona’s seventh Rhodes Scholar, died in 2013.

Born in Los Angeles and raised in nearby San Pedro and the Palos Verdes area, Towne was an English major at Pomona who also studied philosophy under Professor Fred Sontag. Sontag, whom he recalled in a 2010 Pomona Commencement speech as an important mentor, accepted a late paper that allowed him to graduate on time, Towne said.

His Pomona education, Towne said in accepting an honorary doctor of letters degree, “was the best possible training I could have had for my future profession,” though there were no screenwriting classes in the 1950s at Pomona, and possibly not anywhere else. “I don’t think it occurred to anyone it was something to teach,” he said.

“Pomona never taught me the so-called nuts and bolts of my profession, of how to write a screenplay—it gave me a way to view the world so I could write a screenplay,” Towne said.

He concluded his speech with advice that still may resonate with young graduates as they begin their careers.

“Don’t let an uncertain future blind you to the importance of your past. Trust your past,” he said. “Trust your education, even if what you want to do hasn’t been taught yet, or even invented.”

Survivors include his wife Luisa, daughters Kathleen and Chiara, and brother Roger, who co-wrote the adapted screenplay for the 1984 film The Natural.