It was almost dawn outside Lincoln and Edmunds halls, and the clicking of laptop keys on a Saturday morning had slowed to a persistent few. Three students slept in chairs in the Edmunds lobby, one next to a lone coder at his keyboard. In the Lincoln lobby, a quilt lay seemingly abandoned in a clump on the floor. Then it moved, and the petite student who had been slumbering beneath it climbed into a chair and disappeared under the quilt again.

Upstairs, John Verticchio ’15 looked around the windowless room where he’d spent the night working with three friends. “Is the sun up yet?” he asked.

Welcome to the 5C Hackathon, the all-nighter that lures as many as 250 students from The Claremont Colleges each semester to stay up building creative and often elaborate software projects and apps in a mere 12-hour span. It is a deadline-driven, energy-drink-fueled rush to create something that just might become a Silicon Valley startup but is more likely to be remembered as one of those crazily fun things people do in college when they are alight with intelligence and passion.

Welcome to the 5C Hackathon, the all-nighter that lures as many as 250 students from The Claremont Colleges each semester to stay up building creative and often elaborate software projects and apps in a mere 12-hour span. It is a deadline-driven, energy-drink-fueled rush to create something that just might become a Silicon Valley startup but is more likely to be remembered as one of those crazily fun things people do in college when they are alight with intelligence and passion.

The event is student-created and student-led, built from scratch by three Pomona College students in 2012 with a budget of $1,000 and 30 participants. By the fifth 5C Hackathon in April, the budget had grown to $13,000 and the semiannual event had drawn sponsors that have included Intuit, Google and Microsoft. The codefest also is supported by Claremont McKenna’s Silicon Valley Program, which helps students of The Claremont Colleges spend a sort of “semester abroad,” studying while interning at a technology company in Northern California.

The 5C Hackathon is a one-night gig. Competitors are allowed to come in with an idea in mind, but “the rules are that you have to start from scratch. You’re not allowed to have pre-written code,” said Kim Merrill ’14, one of the three co-founders. “It’s all about learning, having fun, staying up all night. It’s not a heavy competition.”

As students wandered into the Seaver North Auditorium around 7 on a Friday night, Merrill, who will go to work for Google as a software engineer in the fall, sat on a table in front wearing shorts and a green H5CKATHON t-shirt as hip music played on the audio system.

The aspiring hackers—how odd that a term that once referred to computer criminals has become a compliment—carried backpacks and laptops, sleeping bags and pillows, the occasional stuffed animal and Google swag bags holding USB chargers, blue Google knit caps and Lego-like toys in boxes emblazoned with the words “google.com/jobs.” This looked like serious fun, and contrary to the stereotypical image of computer geeks, there were women everywhere.

“Having Kim leading the whole thing, I think, has been really powerful for that,” said Jesse Pollak ’15, a former Pomona student who was visiting Claremont for the event he co-founded with Merrill and Brennen Byrne ’12 before leaving school last year to join Byrne in founding a Bay Area startup. (Clef, a mobile app, replaces user passwords on websites with a wave of your smartphone and has been featured by The New York Times.)

“I came in my first year and I knew I wanted to study computer science, and I was hoping there would be, like, a scene here for people who like building stuff, and there wasn’t then. There was nothing,” said Pollak, who didn’t start coding until his senior year in high school. “So I started trying to track down people who were interested in that sort of thing.”

He found them in Byrne and in Merrill, who had planned to be an English major but started coding after an introductory computer science class as a freshman at Pomona.

The event they founded gave the 5Cs an early start on what has now become a national phenomenon. “Hackathons were a new thing and most were on large campuses,” Merrill said.

Hackathons have exploded into prominence in the last two years. The second LA Hacks competition at UCLA in April drew more than 4,000 registrants from universities that included UCLA, USC, Stanford, UC Berkeley and Harvard for a 36-hour event it touted as a “5-star hacking experience” with VIP attendees. Civic groups and government organizations have gotten into the act, too, with the second National Day of Civic Hacking on May 31 and June 1 featuring events in 103 cities, many focused on building software that could help improve communities and government.

While some hackathons have gone grander and glitzier—MHack at the University of Michigan awarded a $5,000 first prize this year and HackMIT drew 1,000 competitors to compete for $14,000 in prizes at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology last year—the 5C Hackathon has remained doggedly itself. “We really wanted, instead of pushing for bigger things, to think about how we can get more people into this,” Pollak said. “You’ll see people present (projects) in the morning who didn’t know how to code at the beginning of the week and who actually built something. It’ll be small and ugly, but it will work.”

While some hackathons have gone grander and glitzier—MHack at the University of Michigan awarded a $5,000 first prize this year and HackMIT drew 1,000 competitors to compete for $14,000 in prizes at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology last year—the 5C Hackathon has remained doggedly itself. “We really wanted, instead of pushing for bigger things, to think about how we can get more people into this,” Pollak said. “You’ll see people present (projects) in the morning who didn’t know how to code at the beginning of the week and who actually built something. It’ll be small and ugly, but it will work.”

A centerpiece of the 5C Hackathon is “Hack Week,” a free beginners’ course of four two-hour evening tutorials leading up to the event, with students teaching other students such basics as HTML and CSS, JavaScript, jQuery and MongoDB, all of it an alphabet soup to the uninitiated.

Christina Tong ’17 tried her first hackathon the fall of her freshman year, picking up ideas during Hack Week that helped inspire her team to fashion a restaurant-ordering app for the Coop Fountain. This spring, continuing to teach themselves more programming languages with online tutorials, her team built a financial tracking system called Money Buddy.

It’s the “forced deadline” of a hackathon, Tong said, that helps coders power through the inevitable snags and bugs of building a program. Pressing on is a huge part of the task. “When you’re fresh, you could probably figure out those bugs decently quickly, but around 3 o’clock, it’s past your normal bedtime and you’re staring for hours at things you probably could fix when you’re fresh,” she said.

Tong’s strategy is catnaps and sustenance. The spring 5C Hackers got an 11 p.m. food truck visit and a snack spread featuring clementines, jelly beans, Oreos, Krispy Kreme doughnuts, bananas and a veggie tray. And at 3 a.m., just because it’s tradition, Merrill—who typically spends much of the night mentoring beginning teams—rallied the students for a two-minute, middle of the night campus run. “It can be hard to motivate people to run at 3 a.m.,” she said.

By 4 a.m., someone had scrawled a message on a whiteboard dotted with listings for tutors: “Countdown 4 hours!”

Some didn’t make it—“I think we lost a lot more teams than we usually do,” Merrill said—but by mid-morning Saturday, 30 teams of two to four people had made one-minute slam demonstrations of their completed projects, roughly half beginners and half advanced.

Judged by America Chambers, a Pomona visiting assistant professor of computer science, and representatives of some of the sponsoring tech companies—this could be the new model of campus recruiting—the entries included efforts such as 5Cribs and the Cyborg Dorm Chooser, designed to help students pick the best dormitory rooms or suites for them.

There was a Craigslist-type site exclusively for The Claremont Colleges and an app to help recreational athletes find a pickup game on campus. One called Expression uses a webcam and face recognition to automatically select music that seems to fit the user’s mood. Another named Echo was a message-in-a-bottle app that allows people to leave audio messages for strangers that can only be heard when the person is standing near the same spot.

The Drinx app suggests cocktail combinations based on what ingredients are in the fridge. But the winning advanced project—sense a theme here?—was the Shotbot, a boxlike robot controlled by a Siri hack that makes mixed drinks automatically. Nonalcoholic, for demonstration purposes.

“Siri loves to serve drinks,” the familiar voice said after taking an order.

“We definitely used it at parties the next few weeks,” said Sean Adler, Claremont McKenna ’14, who built the project, using Arduino, Python, iOS and Node.js, along with three other Claremont McKenna computer science students—brothers Joe and Chad Newbry, both ’14, and Remy Guercio ’16. Their prize? Each team member received an iPad2.

The winners in the beginners’ division, Matt Dahl, Patrick Shao, Ziqi Xiong and John Kim—all Pomona ’17—won Kindle Fires for their project, a “confessions” site similar to other popular sites that allow people to post anonymous secrets or desires. The Pomona students added several features—systems for sorting posts, marking favorites and for hiding offensive content, often a concern on confessions sites.

The next 5C Hackathon will be in the fall, but with Merrill’s graduation in May—she was working for the nonprofit Girls Who Code in San Francisco during the summer before starting at Google in Seattle in late September—the three founders have left Pomona. Andy Russell ’15, Aloke Desai ’16 and Ryan Luo ’16, all of whom helped organize and competed in the spring hackathon, will return to stage more all-night programming binges, the tradition now entrenched.

Russell, his night of coding done, walked out into the quiet of an early Saturday morning, unable to make it to the presentations. He had a Frisbee tournament at 8.

“When I was about five years old, my mom got this new laptop computer,” said Coyiuto. “To me, it looked like the shiniest, best toy ever, but my mom told me I wasn’t allowed to play with it. In the morning, though, I would sneak in the living room and play around with the computer. I discovered this magical thing called Microsoft Powerpoint and I wrote my first story on a slideshow presentation. One day my mom caught me on the computer and instead of scolding me for disobeying her, she read my story. From that day on, I never really stopped writing.”

“When I was about five years old, my mom got this new laptop computer,” said Coyiuto. “To me, it looked like the shiniest, best toy ever, but my mom told me I wasn’t allowed to play with it. In the morning, though, I would sneak in the living room and play around with the computer. I discovered this magical thing called Microsoft Powerpoint and I wrote my first story on a slideshow presentation. One day my mom caught me on the computer and instead of scolding me for disobeying her, she read my story. From that day on, I never really stopped writing.”

Comba never set out to work for a museum. As an undergraduate, he attended the UC Santa Barbara College of Creative Studies, later relocating to Claremont, where he received his MFA in Studio Art from the Claremont Graduate University in 1986. All he wanted was a teaching job that would enable him to pay the rent for his own studio. Until he could find a position, he took a part-time job photographing, mapping and framing prints at the Galleries of The Claremont Colleges, the former museum jointly run by Pomona and Scripps colleges. When two positions at the gallery opened up, Comba inquired about being gallery manager. “I thought it would be more appropriate for a studio artist to be the person who hangs the work, but the curator of collections thought I should look at the position of registrar instead,” he recalls. “My response was, ‘Okay…what is that?’”

Comba never set out to work for a museum. As an undergraduate, he attended the UC Santa Barbara College of Creative Studies, later relocating to Claremont, where he received his MFA in Studio Art from the Claremont Graduate University in 1986. All he wanted was a teaching job that would enable him to pay the rent for his own studio. Until he could find a position, he took a part-time job photographing, mapping and framing prints at the Galleries of The Claremont Colleges, the former museum jointly run by Pomona and Scripps colleges. When two positions at the gallery opened up, Comba inquired about being gallery manager. “I thought it would be more appropriate for a studio artist to be the person who hangs the work, but the curator of collections thought I should look at the position of registrar instead,” he recalls. “My response was, ‘Okay…what is that?’” In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on

In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on  Hong Deng Gao ’15

Hong Deng Gao ’15

After graduating from Pomona with a degree in English, and playing for four years on the Sagehens football team, Kessler jumped right into his current field working at IMG Sports with Tom Condon, ranked by Sports Illustrated as the most influential sports agent in the country last year. Kessler, whose father has been a long-time legal representative for the NFL Players Association, had already served an internship with NBA agent Marc Fleisher while attending Pomona, traveling with 18-year old client Tony Parker to various NBA workouts (Parker has since gone on to win four NBA titles with the San Antonio Spurs and former Sagehen coach Gregg Popovich).

After graduating from Pomona with a degree in English, and playing for four years on the Sagehens football team, Kessler jumped right into his current field working at IMG Sports with Tom Condon, ranked by Sports Illustrated as the most influential sports agent in the country last year. Kessler, whose father has been a long-time legal representative for the NFL Players Association, had already served an internship with NBA agent Marc Fleisher while attending Pomona, traveling with 18-year old client Tony Parker to various NBA workouts (Parker has since gone on to win four NBA titles with the San Antonio Spurs and former Sagehen coach Gregg Popovich).

Take grammar and syntax, the rules that determine how words can be combined into phrases and sentences. Most linguists still insist that animal calls lack these fundamental elements of language. But primatologists studying the vocalizations of male Campbell’s monkeys in the forests of the Ivory Coast have found that they have rules (a “proto-syntax,” the scientists say) for adding extra sounds to their basic calls. We do this, too. For instance, we make a new word “henhouse,” when we add the word “house” to “hen.” The monkeys have three alarm calls: Hok for eagles, krak for leopards, and boom for disturbances such as a branch falling from a tree. By combining these three sounds the monkeys can form new messages. So, if a monkey wants another monkey to join him in a tree, he calls out “Boom boom!” They can also alter the meaning of their basic calls simply by adding the sound “oo” at the end, very much like we change the meanings of words by adding a suffix. Hok-oo alerts other monkeys to threats, such as an eagle perched in a tree, while krak-oo serves as a general warning.

Take grammar and syntax, the rules that determine how words can be combined into phrases and sentences. Most linguists still insist that animal calls lack these fundamental elements of language. But primatologists studying the vocalizations of male Campbell’s monkeys in the forests of the Ivory Coast have found that they have rules (a “proto-syntax,” the scientists say) for adding extra sounds to their basic calls. We do this, too. For instance, we make a new word “henhouse,” when we add the word “house” to “hen.” The monkeys have three alarm calls: Hok for eagles, krak for leopards, and boom for disturbances such as a branch falling from a tree. By combining these three sounds the monkeys can form new messages. So, if a monkey wants another monkey to join him in a tree, he calls out “Boom boom!” They can also alter the meaning of their basic calls simply by adding the sound “oo” at the end, very much like we change the meanings of words by adding a suffix. Hok-oo alerts other monkeys to threats, such as an eagle perched in a tree, while krak-oo serves as a general warning. Berg discovered that parrotlets have names by collecting thousands of the birds’ peeps, then converting them to spectrograms, which he subsequently analyzed for subtle similarities and differences via a specialized computer program. And how does a young parrotlet get his or her name? “We think their parents name them,” Berg said—which would make parrots the first animals, aside from humans, known to assign names to their offspring.

Berg discovered that parrotlets have names by collecting thousands of the birds’ peeps, then converting them to spectrograms, which he subsequently analyzed for subtle similarities and differences via a specialized computer program. And how does a young parrotlet get his or her name? “We think their parents name them,” Berg said—which would make parrots the first animals, aside from humans, known to assign names to their offspring.

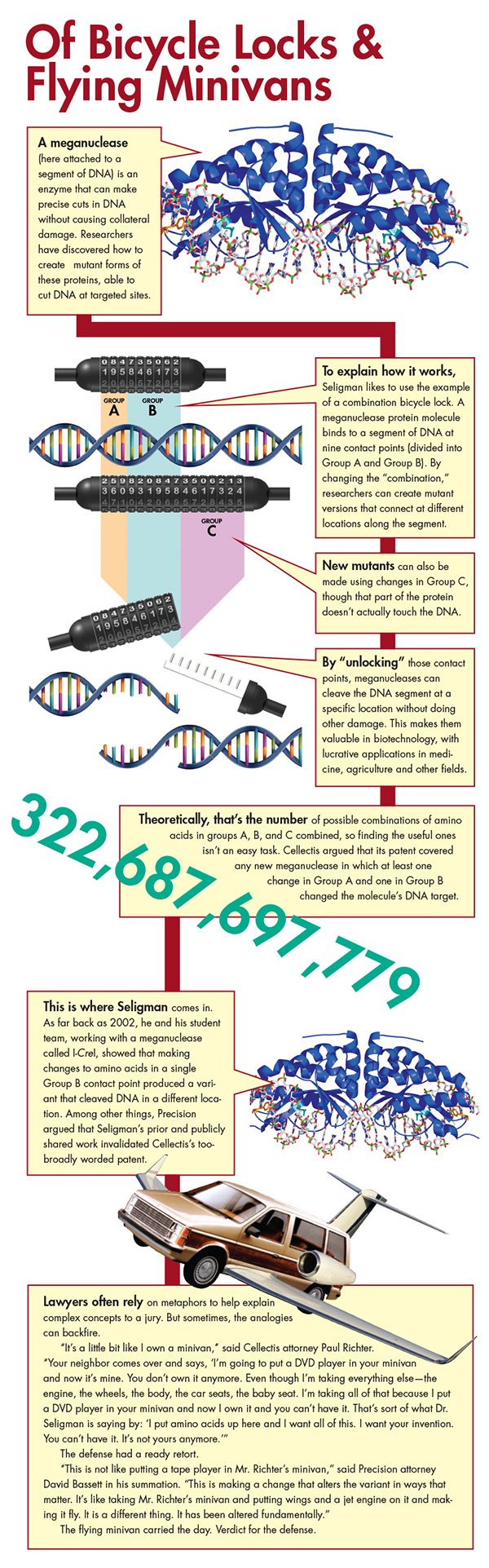

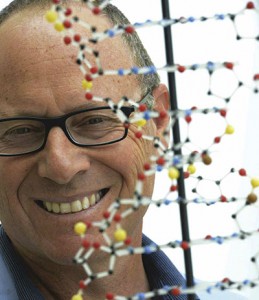

Expert witnesses at contentious trials can expect to be challenged, even discredited. But when he took the stand last year in a complex biotech patent case, Pomona Biology Professor Lenny Seligman never anticipated that his groundbreaking work at Pomona would be relegated to the “ash heap of failure.”

Expert witnesses at contentious trials can expect to be challenged, even discredited. But when he took the stand last year in a complex biotech patent case, Pomona Biology Professor Lenny Seligman never anticipated that his groundbreaking work at Pomona would be relegated to the “ash heap of failure.”