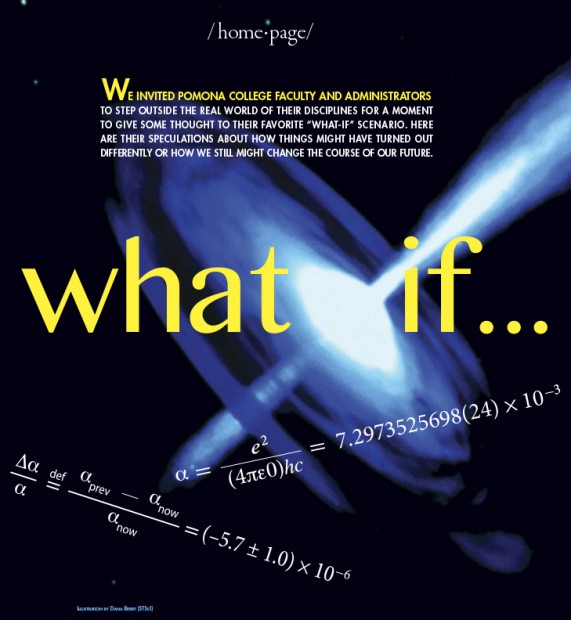

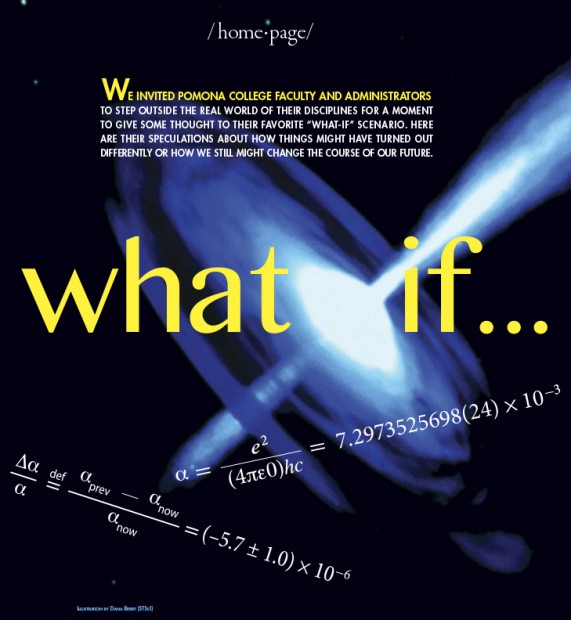

What if the fine structure constant of the universe were changing?

BY BRYAN PENPRASE

Frank P. Brackett Professor of Astronomy

This question is not idle speculation. In fact, it is at the center of a recent controversy in the field of physics and astronomy that is relevant to a topic I have done some research on—quasar absorption lines.

The controversy revolves around the idea that the fine structure constant—usually represented by the Greek letter ‘a’—might be changing with time. The fine structure constant is a dimensionless number that arises from a combination of physical constants and has a big role to play in determining how strongly atoms interact with light. Its value is very close to (but not exactly) 1/137.

The quasar absorption line community has been dealing with this controversy for a couple of decades, and it revolves around a very exacting study of ratios of line strengths in quasar light from very different cosmic times. Some preliminary data from an astronomer named John Webb (then at Cambridge, now in Australia) indicated that he had some evidence for a very microscopic change in this fundamental constant, by about one part in a million.

If found to be true, this slight shift in the fine structure constant would have little impact on our everyday lives, but it would have huge implications for science. For example, it could explain some of the mysteries of astrophysics, such as the phenomenon of “dark energy,” which has vexed astronomers for over a decade (and which won some of the astrophysicists who discovered it a Nobel Prize).

At the same time, the idea that fundamental constants can change with time would completely change how the science of astronomy and astrophysics operates. We postulate that the laws of physics—and the behavior of space and time—are the same everywhere. Known as the “Cosmological Principle,” this idea enables us to use atoms in the laboratory and atoms 10 billion light years away to study nature, since we know these atoms are all the same and obey the same physical laws.

Thankfully (from my point of view, anyway), in 2005 a new study with better and more complete data was able to demonstrate that there was not a change in this value. So the Cosmological Principle is safe after all—at least for now.

What if a better choice of words could have prevented the Hiroshima A-Bomb?

BY SAM YAMASHITA

Henry E. Sheffield Professor of History

At noon on August 15, 1945, the Japanese government officially surrendered to the Allies, ending a horrific conflict that caused the deaths of nearly 15 million people in Asia and the Pacific. The surrender, however, should not have been a surprise. By the spring of 1945, it already was clear that Japan was losing the war. In fact, it was so clear that I have wondered whether the war needed to end in the way that it did, with the atomic bombing of two Japanese cities—Hiroshima on August 6 and Nagasaki on August 9. Could the war have ended earlier, without the dropping of two atomic bombs?

The leaders of the three major Allied countries—the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union—met at Potsdam, Germany, in late July 1945. They were meeting for several reasons: first, to get the Soviets to agree to enter the war as a way of tying down Japanese forces in Manchuria and north China; second, to decide what to do with a defeated Germany; and third, to devise a plan to end the war with Japan.

President Harry Truman went to Potsdam with the news that an atomic bomb had been successfully tested in New Mexico. So as Truman, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin discussed the invasion of Japan—scheduled for 1946—they knew they had an ace up their sleeve: the atomic bomb. Even as they planned for the invasion, they hoped that the threat of this new bomb would lead the Japanese to surrender. This was the thinking behind the Potsdam Declaration, the communication sent to the Japanese on July 26, 1945.

The declaration included the following seven points: first, now that Germany had surrendered, the Allies would turn their full attention to Japan; second, this would mean the destruction of Japan; third, the Japanese people must free themselves from the control of their “self-willed militaristic advisers … who had deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest”; fourth, Japan would be occupied by the Allied forces; fifth, Japan’s armed forces would be disarmed and demilitarized; sixth, Japan would lose its territorial possessions; and finally, the last article of the document read: “We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

We know now that the last sentence—“the alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction”—referred to the atomic bomb.

The Japanese authorities studied the document, but in the end the Suzuki cabinet decided to ignore it, “to kill it with silence” (J. mokusatsu). One of the sticking points may have been the following reference to the emperor in a follow-up message from the Allies: “From the moment of surrender the authority of the emperor and the Japanese government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers.”

The phrase “shall be subject to” was variously translated: the Foreign Ministry translated it as seigen no shita ni okareru, “will be placed under the restrictions” of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers. The War Ministry rendered it as reizoku sareru, or “be subordinated to,” the implied subordination being like that of a vassal to his lord. The War Ministry’s translation may explain the Suzuki cabinet’s decision “to kill [the invitation to surrender] with silence” and the reluctance of so many at the highest levels of the Japanese government to accept the Potsdam Declaration.

The Allies responded by dropping an atomic bomb on Hiroshima on August 6 and then another on Nagasaki on August 9. Is it possible that the dropping of the first atomic bomb could have been averted if a key phrase in the Potsdam Declaration had been rendered differently in English?

What if the Athenians had not invented democracy in 508 B.C.?

BY BENJAMIN KEIM

Assistant Professor of Classics

Twenty-five centuries after the battlefields fell silent, echoes of the Persian Wars still resonate. Out of those heroic struggles arose an unparalleled cultural efflorescence, rooted within Athenian theatres and thinkeries, that would first blossom across the Mediterranean and then be grafted into the stock of world civilization.

Twenty-five centuries after the battlefields fell silent, echoes of the Persian Wars still resonate. Out of those heroic struggles arose an unparalleled cultural efflorescence, rooted within Athenian theatres and thinkeries, that would first blossom across the Mediterranean and then be grafted into the stock of world civilization.

Speculations about these battles and their ramifications may be traced all the way back to Herodotus’ Histories, and historians continue to ask serious questions about Athenian policies and personnel today. The most significant element underlying Athenian strength and Greek victory, however, was political: the Athenians’ revolutionary move to democratic governance.

Prior to 508 B.C., Athens had accomplished very little of note on the Greek stage, despite her great territorial and demographic advantages. That year, however, after deposing one tyrant and resisting Sparta-led efforts to install another, the Athenians embraced the equality of all citizens, and the effects of this revolutionary constitutional change were felt immediately. Carefully re-organized by Cleisthenes’ democratic institutions and strongly motivated by their newfound freedom and opportunity, the Athenians poured out their blood and treasure for the sake of freedom.

On papyrus, the Persian forces were overwhelmingly superior. The Achaemenid Dynasty ruled a cosmopolitan empire of unrivaled wealth, its 70 million subjects spread from the shores of the Mediterranean to the Himalayan heights. When Darius first gazed westwards in 493 B.C., scores of Greek city-states immediately pledged their fealty. But not all Greeks would “Medize’ so easily. The Spartans and the Athenians, asked for the earth and water that symbolized submission, foreshadowed their unwavering resistance by throwing the unlucky heralds into nearby wells.

At Marathon in 490 B.C., nearly half the Athenian citizenry mobilized, 10,000 hoplites fighting with barely any allied support against 30,000 Persians. Advancing rapidly into the fray, the Athenians drove their enemies out of Greece. However, Xerxes redoubled his efforts, and his vengeance seemed assured. Under the Great King’s watchful eye the Persians marched into Greece in 480 B.C., annihilated the Spartans at Thermopylae, then occupied Athens and razed the Acropolis. Bent but unbroken, the Athenians responded vigorously: Themistocles drew the Persian navy into the straits off Salamis, then led the Greek fleet, featuring 200 crack Athenian triremes, to victory. After their defeat at Plataea the following summer, the Persians retreated and never again campaigned in mainland Greece.

Athens’ starring role within these victories enhanced her prestige and led her to challenge Sparta for hegemony over Greece. Without their earlier embrace of democracy, however, the Athenians would neither have withstood the Persians nor flourished so brilliantly. As a result, both the political landscape and the cultural heritage of the ancient Mediterranean would have been dramatically altered. Historically, there would have been no Greek victory at Marathon, much less Salamis or Plataea. Although the Spartans might well have resisted to the death, neither their numbers nor their tactics could delay Persian capture of the Peloponnese. Greece would have become yet another Persian satrapy in 490 B.C.

No matter how benevolent Achaemenid rule really was, the Athenians would not have enjoyed the power and profits that accrued from their own fifth-century naval empire and that underwrote the ‘Golden Age’ of Pericles. Shorn of their freedom, the Athenians would not have had the opportunity to refine those political and economic institutions that, taken up by Philip and Alexander, allowed the Macedonians to conquer first Greece and then the Persian Empire. Without Marathon, then, there would be neither Alexander the Great nor the Romans as we know them.

Culturally, democratic Athens encouraged the free speech and debate that enabled the philosophic enquiries of Socrates and Plato, the critical historiography of Herodotus and Thucydides, the artistic perfection of Pheidias and the Parthenon, and the tragedies that continue—as with this autumn’s staging of Luis Alfaro’s Mojada: A Medea in Los Angeles—to provoke and inspire. It was the military and intellectual strength of democracy that enabled Athens to become first the ‘School of Hellas,’ then of the Mediterranean, and thereafter the entire world.

What if math were not required in K-12 education?

BY GIZEM KARAALI

Associate Professor of Mathematics

Let me turn this around and ask what if all kids were forced to take regimented and stifling music classes through their K–12 years? What if they were tested yearly, through multiple-choice high-stakes tests, in their music skills? What if students of music were not allowed to listen to a real musical composition until they could “appreciate it”—which would, of course, be in college, only if they made it that far, of course… What if students were not even allowed to touch a real musical instrument until they learned all the basics—you know, the notes, the chords, the names of famous composers and all that stuff? What if government bodies and corporate entities alike kept pushing for more and higher standards to ensure that our nation’s competitive advantage, musical potential, would not disappear?

If you’re up for it, also try the artist’s nightmare for size. Imagine a world where young children are not allowed to touch crayons, water colors, even a colored pencil, before they learn all their primary and secondary colors, their hues and tones, their shades and perspectives, and all that which could conveniently be tested in a high-stakes test, to be systematically administered yearly of course… This would be justified by policy statements urgently calling for improvements in the nation’s art education, for of course, our students could not fall behind students of all those other nations, or else our competitive edge, our creative potential, would be compromised!

Math teacher Paul Lockhart writes in A Mathematician’s Lament that the current state of mathematics education is analogous to the above two scenarios. Math in K-12 is taught out of context, without regard to intellectual need and curiosity, and in a uniformly linear fashion. School math often leaves out the cool stuff, the fun stuff, the naturally interesting and absolutely fascinating parts, and focuses almost exclusively on what can be tested. Students are “assessed” regularly and classified into those who can and those who cannot do math. Various entities whose existential purposes have nothing to do with the education of the nation’s future generations pontificate recklessly about how best math teachers should perform their craft.

And so we get students who arrive at college with no idea what math really is about. Some like it that way, but many have been totally turned off. All have concluded, through extensive experience that does not yield to any alternative readings, that math is about rules to be memorized and regurgitated when requested. That there is only one answer to each question and that there is only one best way to get at it. That some are naturally born with the math gene and others remain hopeless no matter what they do.

At Pomona, it is our pleasure to disabuse those unlucky to have gone through a standard K–12 education of these beliefs. We love to help students discover for the first time what math is really about (hint: it has more to do with playful curiosity and stubborn stick-to-itiveness than memory). How math is really expansive and accessible to anyone who wishes to learn more. How math does not really have to be linear (there are multiple entry points to our curriculum and not much that is linear in our major at Pomona). Why math can actually be fun (Tetris, Sudoku, and that 2048 game are addictive; what math is hidden in your favorite pastime?). But wouldn’t it be lovely if we didn’t have to do that? Erasing false beliefs is hard. And it is unpleasant to have to go uphill all the time. Wouldn’t it be lovely if students came in with no pre-conceived opinions of what math is about?

What if all landscaping were done with local-native plants?

BY WALLACE MEYER

Assistant Professor of Biology and Director of the Bernard Field Station

Welcome to the Anthropocene, the current epoch characterized by the significant influence of human activities on Earth’s systems. While this term typically conjures negative aspects of human influence on the world’s ecosystems and the daunting environmental challenges our society is facing (e.g., global climate change, habitat destruction, biodiversity loss, and increased toxin and nutrients inputs), it also highlights that humans have the power to make transformative change.

The task for scientists and policy makers is to develop easy-to-articulate policies that effectively utilize limited resources and transform our understanding of and relationships with our local ecosystems. Unfortunately, too often policies are myopically focused on one resource, undermining transformative change and long-term sustainability.

For example, policies, largely successful from the perspective of water conservation, have asked residents to limit water use to appropriate times and activities and transform landscapes from water extractive lawns to more water-wise gardens. While I applaud the successful efforts of individual residents, these policies have not instituted transformative change.

More impactful would be a policy that required all urban/suburban areas be landscaped with only local native plants. I use the term “local-native” to distinguish from the commonly used term “native.” Local-native plants are plants that are native to a particular area. In Southern California’s low-elevation areas, local plants would include white sage and elderberry, not a redwood tree, which would be considered a California native.

Such a policy would differ from the one that only requires water reductions because local-natives have evolved to cope with the abiotic conditions (temperature, water availability, etc.), and do not require any water inputs once established. Second, local-native plants support local animals and fungi. Since the native ecosystem type (California sage scrub) in SoCal’s low-elevation areas is endangered and many species require it for their survival, significant conservation progress may be achieved. Third, policy focused only on water resources ignores other complex interactions that occur when people modify the landscape. For example, increased use of mulch to reduce water loss facilitates establishment of non-native arthropod species (isopods and Argentine ants) by providing a moist habitat, and potentially represents a significant source of CO2 through UV photo-degradation.

This “local-native” regulation would also transform our eco-literacy. Many residents have never heard the term California sage scrub but need to understand this habitat and become familiar with the species that inhabit it, if we genuinely intend to build a sustainable future with diverse biotic/regional communities that can provide us valuable services (e.g., carbon storage). Long-term sustainability requires a holistic approach incorporating climate change mitigation, biodiversity preservation, wise use of vital resources and an educated public. In the Anthropocene, human actions will decide the future. If you intend to be part of the solution, some good initial steps in its construction would be to: (1) learn about your amazing local-native plants (my favorite is royal penstemon), (2) re-envision/plant your landscape and have it teach you and others about adaptation to and survival in the local conditions, and (3) make it beautiful to inspire others to follow your lead.

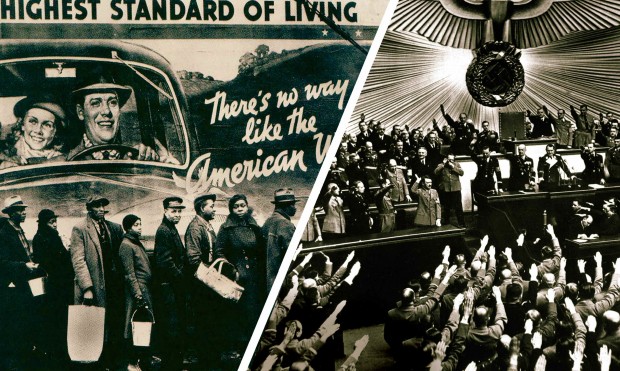

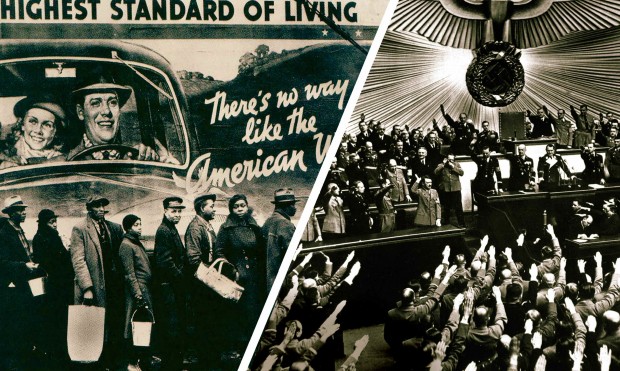

What if Keynesian ideas had shaped policy during the Great Depression

BY JAMES LIKENS

Professor Emeritus of Economics

Before the publication of John Maynard Keynes’ great treatise, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, in 1936, conventional economics held that discretionary economic policy could not affect the real economy. Intervention would not help overcome unemployment, and naïve attempts to do so would actually undermine the effective workings of markets. Keynes, in contrast, showed the way to contain economic recessions through stimulating aggregate demand. His insights revolutionized economics.

The Great Depression began in the United States in 1929 with the collapse of the stock market, which set off a wave of bankruptcies and defaults that spread rapidly around the world. Germany and to some extent Great Britain, which were the most indebted to the U.S., were hit the hardest.

What if the Keynesian insights of The General Theory had been understood by policy makers as early as 1928? There doubtless would have been a serious recession in the U.S. and abroad, but not the disaster of the 1930s that actually occurred. Policy makers in the 1930s would have followed Keynesian practices and stimulated aggregate demand through discretionary fiscal policy. This would have reduced both the length and severity of that depression.

After World War I, Germany suffered from heavy reparation payments and hyperinflation, so it had lots of problems. But wise Keynesian countercyclical policy probably could have helped its economy to recover. Also important, the economic contagion from the United States would also have been less severe in Germany had the U.S. itself been following Keynesian practices. Unemployment in Germany consequently would not have reached 30%, as it did in 1932, to usher Hitler and the Nazis into power.

There still might have been wars. Italy and Japan would probably still have set out as colonial powers to conquer new territory. But had the insights of Keynes been available 10 years earlier and embraced by the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations and the Fed, Hitler and the Nazis might well have never come to power, and there would have been no World War II in Europe.

As Keynes said, “…the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else.”

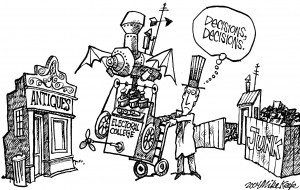

What if the Electoral College didn’t exist?

BY SUSAN McWILLIAMS

Associate Professor of Politics

In one very real sense, the Electoral College doesn’t exist: It has no location. Its members—the 538 electors, who are chosen by and bound to a hodgepodge of state-level rules—never gather as a single body.

Instead, during presidential election years, on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December, the electors meet in their respective states and cast votes, on separate ballots, for president and vice president. Shortly thereafter, on January 6, a joint session of Congress oversees the counting of electoral votes by state. The sitting vice president, acting in his (or someday, God willing, her) capacity as president of the Senate, then announces the results of the ballots and who, if anyone, has received the necessary 270 electoral votes to be named the next president and vice president of the United States, respectively.

It’s a weird enough seeming system that there are always proposals to dismantle it, usually in the name of democracy or transparency. Currently, the National Popular Vote movement tries to do an end run around the Electoral College by asking state legislatures to pledge their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote.

So: what if the Electoral College really didn’t exist?

The obvious thing to say is that if the Electoral College didn’t exist, the presidency and vice presidency would be chosen by a simple majority of American voters.

That change would in turn spur changes in presidential campaigns. Today, under the Electoral College system, candidates try to maximize their chances of winning by focusing their campaigns, especially their late-stage campaigns, in a series of “swing states” which have significant numbers of electoral votes and a mixed electorate—the states that thus might be the determining factor in an election (like, recently, North Carolina, Ohio and Indiana).

Were there no Electoral College, campaigners would calculate differently. Most likely, we’d see presidential candidates focus on high-density urban areas and power centers. After all, in cities you can access the most voters, most efficiently—not to mention the most wealth. So campaigns would likely home in on places like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Houston. We’d see little late-stage campaigning in Ohio. And we’d hear ever more about issues that concern residents (and especially elite residents) of large cities. There would be a lot less discussion of agriculture policy; that’s for sure.

It’s also imaginable that absent an Electoral College, a candidate might choose to focus on just one section of the country. It’s impossible to win with that approach in the current system, but under simple majority rules, a candidate can win by dominating the vote in a limited region. Consider 1888, when my distant cousin Grover Cleveland won the popular vote but lost in the Electoral College. That happened because cousin Grover had disproportionate support in the South but pretty much nowhere else. (This is the kind of thing that defenders of the Electoral College imagine when they say that in a simple majority system, it’s much easier to win by catering to ideological extremes.)

Those shifts in campaigning would, in turn, change other aspects of how we think about American politics. We’d hear less red-state/blue-state talk, since votes would no longer be organized at the state level. We’d have more neglect of, and alienation in, rural America (which already has a poverty rate higher than that of urban America). We’d see the further weakening of our already weakened political parties, with a corresponding growth in the already grown influence of corporate and personal wealth in politics; that’s because candidates would depend less on state-level party organizations in particular, while they’d depend more on raising money to mount their own, individual campaign strategies. (Note that although a majority-vote system would be a formally more democratic system of governance, a majority-vote system also leads to consequences that create effectively less democratic governance.)

One thing, though, above all is sure: If there were no Electoral College, we’d spend a lot less time listening to political scientists talk about the Electoral College. That, at the very least, might be a thing worth imagining.

What if Pomona had not built a strong endowment?

BY KAREN SISSON ’79

Vice President and Treasurer

Where would we be if Pomona had never changed the way it managed its endowment? In the late 1970s, then Treasurer Fred Moon approached President David Alexander about a “new” approach to investing the College’s endowment. The traditional investment formula at that time was to invest a college endowment in a combination of stocks and bonds. Typically, a higher percentage would be invested in stocks. Treasurer Moon suggested that a different approach might result in better returns on the College’s investments. Moon was acquainted with an investment advisor at Harvard who had formed his own firm and was recommending an “asset allocation” approach to investments. A more quantitative approach, the idea was to create a portfolio of diversified investments over a wide variety of asset classes—real estate, commodities, private equity, venture capital, stocks and bonds—that would be less volatile than a typical stock and bond mix but also yield better returns.

President Alexander and the Board of Trustees agreed and a long and productive relationship with Cambridge Associates and the implementation of the asset allocation strategy began. Since that time the endowment has grown from approximately $117 million in 1985 to over $2 billion today, fueled not only by outstanding investment performance but also by new gifts from donors and the reinvestment of earnings. Today, income from the endowment funds over 40 percent of the College’s operating budget, including 35 percent of faculty salaries through donor-endowed chairs and 40 percent of the College’s financial aid to students. Needless to say, the endowment is what has made it possible for Pomona to stay need-blind in admissions, package financial aid without loans and meet each student’s full financial need.

You can also see the endowment at work in Pomona’s campus—new sustainable buildings like the LEED Gold Studio Art Hall, the new LEED Platinum Millikan Laboratory and Andrew Science Hall, LEED Gold Pomona and Sontag halls all were paid for with contributions from endowment income in addition to generous donor contributions. Due in large part to the endowment, sustainable building practices and landscaping are the norm on the Pomona campus. The renovation of buildings bordering the Peter Stanley Academic Quadrangle and the repurposing of parking lots to create new open spaces like those between Mudd-Blaisdell Hall and Harwood Court and the Big Bridges North Portico patio also benefitted from endowment income. That income also provides generous support to the Claremont Colleges library materials budget as well as research and materials for numerous College departments through donor-restricted gifts.

It is hard to find a part of the Pomona community that has not benefitted from the endowment. When we celebrate our outstanding faculty and small class sizes, the beauty of our sustainable campus and the richness of our student body, we should keep in mind the contribution of donors over time and that first conversation between Fred Moon and President David Alexander.

Board Chair Samuel D. Glick ’04

Board Chair Samuel D. Glick ’04

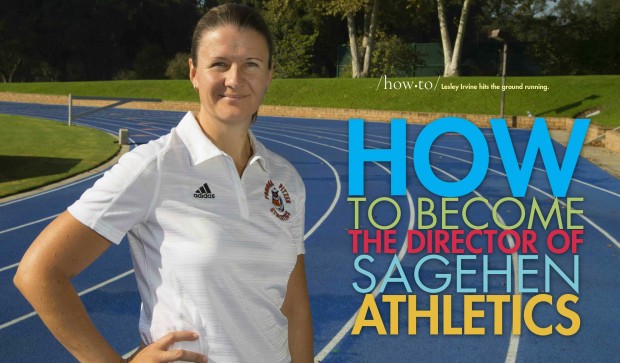

There’s nothing particularly surprising in the fact that Pomona-Pitzer’s new athletic director has hit the ground running. Lesley Irvine has been moving fast ever since she was a child—first as a multi-sport athlete, then as a high-profile coach and finally as an athletic administrator. At Pomona, she has assumed a newly created full-time position as chair of Pomona’s Physical Education Department and director of the joint athletic program of Pomona and Pitzer colleges.

There’s nothing particularly surprising in the fact that Pomona-Pitzer’s new athletic director has hit the ground running. Lesley Irvine has been moving fast ever since she was a child—first as a multi-sport athlete, then as a high-profile coach and finally as an athletic administrator. At Pomona, she has assumed a newly created full-time position as chair of Pomona’s Physical Education Department and director of the joint athletic program of Pomona and Pitzer colleges. Grow up in Corby, a steel town in central England where most people are of Scottish descent and speak with a Scottish brogue. Develop into an active child, always sporting a scraped knee. Get involved in athletics with the encouragement of your dad, an avid soccer player, coach and fan.

Grow up in Corby, a steel town in central England where most people are of Scottish descent and speak with a Scottish brogue. Develop into an active child, always sporting a scraped knee. Get involved in athletics with the encouragement of your dad, an avid soccer player, coach and fan. Join a track and field club at the age of 9 and, since you excel in a range of athletic events, specialize in the heptathlon. In high school, find yourself playing almost every sport, from basketball to volleyball to soccer. Discover the game of field hockey and fall in love with it.

Join a track and field club at the age of 9 and, since you excel in a range of athletic events, specialize in the heptathlon. In high school, find yourself playing almost every sport, from basketball to volleyball to soccer. Discover the game of field hockey and fall in love with it. Accept an invitation to play on the English junior national field hockey team at the age of 16, while also competing internationally in the heptathlon. Play for England in a victory over Scotland in the Six Nations field hockey tournament and have to explain to your teammates why your dad, a proud Scot, is rooting against you.

Accept an invitation to play on the English junior national field hockey team at the age of 16, while also competing internationally in the heptathlon. Play for England in a victory over Scotland in the Six Nations field hockey tournament and have to explain to your teammates why your dad, a proud Scot, is rooting against you. Become the first member of your family to go to college, playing field hockey at prestigious Loughborough University. While there, win five national championships. During your second year, teach tennis at a summer camp in Maine (though you’ve never touched a tennis racquet before) and find yourself at home in American sports culture.

Become the first member of your family to go to college, playing field hockey at prestigious Loughborough University. While there, win five national championships. During your second year, teach tennis at a summer camp in Maine (though you’ve never touched a tennis racquet before) and find yourself at home in American sports culture. After graduating, come back to the U.S. for graduate school, attending the University of Iowa and playing competitive field hockey for one more year, scoring the only goal in a 1–0 victory over Stanford University in your first trip out West and leading your team to a Final Four appearance. Earn your master’s degree in health, leisure and sports studies.

After graduating, come back to the U.S. for graduate school, attending the University of Iowa and playing competitive field hockey for one more year, scoring the only goal in a 1–0 victory over Stanford University in your first trip out West and leading your team to a Final Four appearance. Earn your master’s degree in health, leisure and sports studies. Return to Stanford as assistant women’s field hockey coach. Discover that you love working with committed student athletes who love sports as much as you do. After two years, succeed the retiring head coach and spend eight years at the helm of Stanford’s elite program, guiding them to three straight NorPac championships.

Return to Stanford as assistant women’s field hockey coach. Discover that you love working with committed student athletes who love sports as much as you do. After two years, succeed the retiring head coach and spend eight years at the helm of Stanford’s elite program, guiding them to three straight NorPac championships. Leave Stanford to enter sports administration, spending five years at Bowling Green State University and rising to the rank of senior associate athletic director. Decide the job at Pomona-Pitzer is a perfect match for your abilities and your desire to help build something special for talented and motivated student-athletes while promoting wellness for a whole community

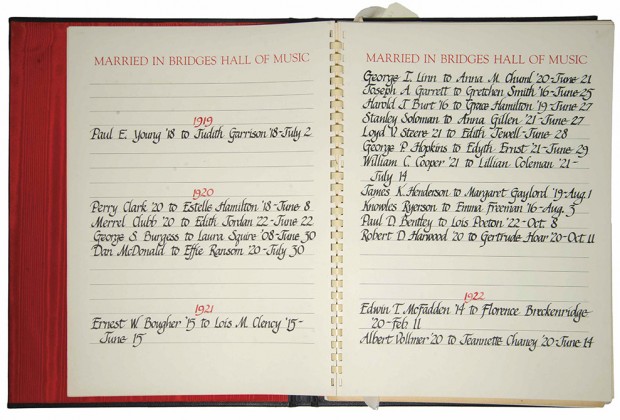

Leave Stanford to enter sports administration, spending five years at Bowling Green State University and rising to the rank of senior associate athletic director. Decide the job at Pomona-Pitzer is a perfect match for your abilities and your desire to help build something special for talented and motivated student-athletes while promoting wellness for a whole community As Bridges Hall of Music celebrates its centennial, many Pomona alumni look back fondly at the place where they said “I do.” The Little Bridges Wedding Register is a historical record of marriages that took place in the building, starting with Howry Warner 1912 and Mary Roof 1912, married June 1, 1916. Compiled in the early 1970s, the register was maintained and updated through 1992 and includes the names of 453 couples.

As Bridges Hall of Music celebrates its centennial, many Pomona alumni look back fondly at the place where they said “I do.” The Little Bridges Wedding Register is a historical record of marriages that took place in the building, starting with Howry Warner 1912 and Mary Roof 1912, married June 1, 1916. Compiled in the early 1970s, the register was maintained and updated through 1992 and includes the names of 453 couples.

Twenty-five centuries after the battlefields fell silent, echoes of the Persian Wars still resonate. Out of those heroic struggles arose an unparalleled cultural efflorescence, rooted within Athenian theatres and thinkeries, that would first blossom across the Mediterranean and then be grafted into the stock of world civilization.

Twenty-five centuries after the battlefields fell silent, echoes of the Persian Wars still resonate. Out of those heroic struggles arose an unparalleled cultural efflorescence, rooted within Athenian theatres and thinkeries, that would first blossom across the Mediterranean and then be grafted into the stock of world civilization.

Comedian Joel McHale entertained a packed house of Claremont Colleges students at Little Bridges on Saturday night.

Comedian Joel McHale entertained a packed house of Claremont Colleges students at Little Bridges on Saturday night.