Thirteen years ago, as David Oxtoby was preparing to become the ninth president of Pomona College, this magazine introduced him to the College family with an article titled “The Elements of a President.” The title arose from a reference to one of his favorite books, The Periodic Table.

Oxtoby Memories, Part 1

In my mind, he was a guy who thrived on opening new doors, and who didn’t shy away from difficult situations.

—Stewart Smith ’68

Former Chair of the Board of Trustees

He really believed in my potential, and he reminded me of that constantly.

—Shirley Ceja-Tinoco ’10

Read more Oxtoby memories.

In this autobiographical work, Italian chemist and Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi famously titled each chapter with an element that he had worked with as a chemist or that was related in some symbolic way to his life.

Asked which elements he would choose to describe his own life, Oxtoby—as a fellow chemist with a similarly figurative turn of mind—played along.

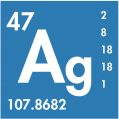

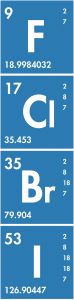

He started with hydrogen, the first and simplest element, symbolizing his formative years. Next came gallium, an element with some odd properties that interested him in his research on nucleation, as well as being named in honor of France, the country where he met his wife, Claire. Chlorine, bromine and iodine, all part of the halogen family, represented his three children. All, he said, were part of a single family and yet each was utterly distinctive in character. To symbolize his years of teaching and research in atmospheric chemistry, he chose carbon, the key element for life. Finally, for his arrival at Pomona, he selected element number 47 on the periodic table, silver.

So naturally, as Oxtoby’s tenure as Pomona president entered its final months, we went back to him to ask how he would revise or add to that list today to characterize his presidency. Once again, he played along, and the result is a metaphorical reflection on some of the key themes of his transformative tenure at Pomona.

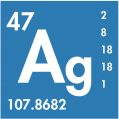

Silver / The Liberal Arts

Silver / The Liberal Arts

“This time, I would start with silver, element number 47, therefore the Pomona element. A noble metal, it is important both aesthetically in the arts and as a catalyst for new chemistry, and so, it could be a symbol not only of Pomona, but more broadly of the liberal arts.”

Oxtoby Memories, Part 2

David is not only a renowned scientist, but a powerful advocate for the arts.

—Louise Bryson

Trustee

I remember him telling us that our job was to do what was right, not what was popular.

—Lori Kido Lopez ’06

Read more Oxtoby memories.

Some aspects of a presidency are easily quantifiable—gifts raised, buildings built, programs launched. Others, though equally important, are harder to measure. David Oxtoby’s role as an international ambassador for the liberal arts falls into the latter category.

A chemist who had spent his entire career up to that point at large research universities, Oxtoby began his inaugural address with these words: “What is a liberal arts college today, in 2003?” He went on to make the case for an education that is broad, personal, and full of opportunities to follow one’s passions.

“Growing up as he did on the Bryn Mawr College campus with a father who was a prominent faculty member,” says longtime colleague Richard Fass, who served as Pomona’s vice president for planning until his retirement this year, “David developed and retained a firm belief in the values of a liberal arts education. He cares about the enterprise we’re all engaged with and believes deeply that there is no better way to develop educated and committed minds and hearts. David’s passion and commitment are infectious.”

That infectious passion was apparent as the years went by, and Oxtoby became a national spokesperson for the continuing importance of liberal arts colleges, writing and speaking about the future of the liberal arts and its response to such challenges as the growth of interdisciplinary study and globalization.

He even carried his message around the globe, traveling to India, Hong Kong and Singapore to offer support to local educators working to adapt the successful American liberal arts model to their own cultures while learning from them in exchange.

“Given the ongoing debate here at home about the value of a liberal arts education, it was good to be reminded that we’re all part of an international competition in which U.S. higher education is considered the gold standard, in large part because of its breadth and multiple pathways, including a vigorous liberal arts tradition,” he said in a letter to alumni.

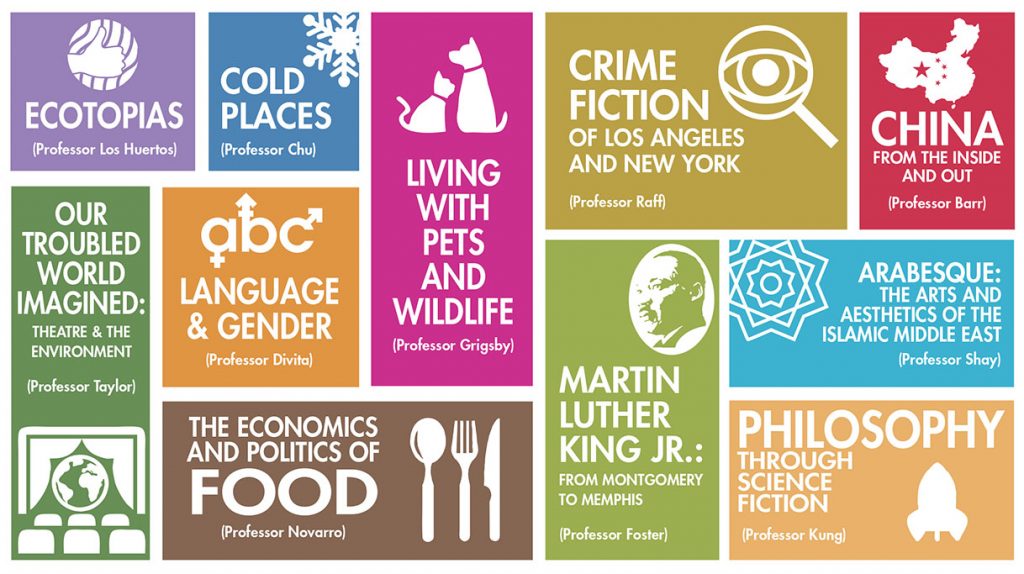

While promoting the liberal arts tradition nationally and abroad, Oxtoby also focused throughout his presidency on reinforcing it here on our own campus. He worked with the faculty to restructure Pomona’s overly restrictive general education program to give students more freedom of choice. He led a campus-wide renewal of Pomona’s commitment to the arts, including the construction of a new Studio Art Hall that is now inspiring more students to explore the arts. In the final year of his presidency, he is continuing this work by spearheading the College’s ongoing initiative to provide the Pomona College Museum of Art with a new home suitable for a state-of-the-art teaching museum for the 21st century.

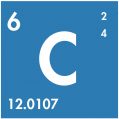

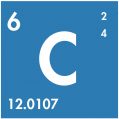

Carbon / Sustainability

Carbon / Sustainability

“Carbon now makes me think of sustainability, about CO2 and carbon taxes. We think a lot these days about bad carbon, carbon that’s implicated in global warming and climate change, but it’s also the central element of life.”

Oxtoby Memories, Part 3

I think President Oxtoby is probably one of the most outspoken leaders on college campuses when it comes to sustainability.

—Tom Erb ’18

I’ve always been inspired by his deep commitment to fighting climate change.

—Sen. Brian Schatz ’94

U.S. Senator from Hawaii

Read more Oxtoby memories.

As a noted atmospheric chemist who taught classes in environmental chemistry throughout his presidency, Oxtoby brought an expert perspective and a degree of credibility to the topic of sustainability that few of the nation’s college leaders could match. His record in promoting sustainability as a shared, campus-wide commitment began early in his presidency with his involvement in strengthening the still relatively new Environmental Analysis Program and preserving of the Organic Farm as an officially sanctioned part of the campus.

Completed the year after his arrival, the Richard C. Seaver Biology Laboratory became Pomona’s first building to earn a LEED certification (silver) from the U.S. Green Building Council. That, however, was only the start. Over the following 12 years, with a commitment by the Board of Trustees to sustainable construction of all new facilities, the College would complete four new academic buildings, two new residence halls, and a three-building staff complex, all LEED-certified at the gold or platinum level. Even the College’s new parking structure, in a category of buildings that doesn’t qualify for certification, was built to LEED gold standards.

In early 2014, when Oxtoby set an ambitious goal for the campus to reach net climate neutrality by 2030, he looked back at some of the progress that has been made: “We are working across campus in new and exciting ways to integrate sustainability into our culture. Some highlights of increased engagement include the establishment of the President’s Advisory Committee on Sustainability (PACS) to oversee campus sustainability effort and the launch of Sustainability Action Fellowships to fund student involvement in campus sustainability planning. New staff members are managing sustainability efforts and the Organic Farm, and our recent addition of an energy manager will help the College heat, cool and light buildings in more sustainable and efficient ways. Together, we are creating a greater level of consciousness about sustainability across the campus and showing how small and large choices add up to real results.”

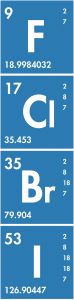

The Halogens / Diversity

The Halogens / Diversity

“Fluorine, chlorine, bromine and iodine are all members of the halogen family but they look different and have different properties. Now that strikes me as a wonderful symbol of diversity. We’re all a single family, the Pomona family; we have lots of things in common, but we’re all distinctive as well, and we value and celebrate both our commonalities and our differences.”

Numbers never tell the whole story, but sometimes they make for a good starting point. In 2003, the percentage of students of color in the Pomona student body stood at 27%. Today, 48% of Pomona students are students of color, making Pomona one of the most diverse liberal arts colleges in the nation. Over the same period, the College’s international student population has grown from 2% to 12.5%.

Oxtoby Memories, Part 4

I believe our students will reap the benefits of his leadership for decades to come.

—Ric Townes

Associate Dean of Students

What struck me about David when I first met him was his deep personal humility.

—Karen Sisson ’79

Vice President and Treasurer

Read more Oxtoby memories.

Behind those numbers were determined and sustained efforts to expand the College’s outreach. “It is not enough for us simply to wait for students from different backgrounds to apply,” Oxtoby said in 2006. “We must be proactive in identifying and encouraging them.”

Among other things, that meant building strong partnerships with such organizations as the Posse Foundation and Questbridge, which now serve as conduits for highly talented students from underprivileged backgrounds across the country. The College has also built its own program to help promising high school students from the College’s own backyard prepare themselves for success at top colleges. Today, the Pomona College Academy for Youth Success (PAYS) still holds a perfect record in gaining its graduates admission to four-year colleges and universities, including Pomona.

Internationally, the college not only stepped up recruiting in Asia; it also expanded its range into South America and Africa. By extending more financial aid to international students, the College also succeeded in broadening the demographics of international students to align with the College’s goal to make the college accessible to the most talented students from all backgrounds.

In 2008, under Oxtoby’s leadership, the College also made the commitment to treat all applicants who graduate from U.S. schools the same, whether or not they are documented, thereby enabling undocumented students to compete for admission and aid on a level playing field.

However, Oxtoby has also made clear that there is still a great deal of work to be done here on campus in building a more inclusive climate in which every member of this diverse community can feel equally welcome and invested. “I have several priorities I am focusing on in my last year as Pomona College president,” he wrote earlier this year. “Chief among these are advancing a culture of respect and building a more inclusive environment in the classroom and on campus. These goals are essential to the bold and scholarly work we do.”

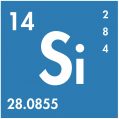

Silicon / Innovation

Silicon / Innovation

“Silicon is the namesake of Silicon Valley, but in truth, every valley is a kind of silicon valley, since silicon is the basic building block of every kind of rock. But when you separate it out, it becomes solar cells and semiconductors. It’s not a metal or a non-metal, but a bridging element—that’s the crucial aspect that allows it to expand our ability to do things and to innovate. So in a way, it symbolizes the future.”

Oxtoby Memories, Part 5

You could see in his eyes that he cared a lot about the Sontag Center.

—Fred Leichter

Founding Director of the Sontag Center for Collaborative Creativity

That’s David’s gift, to engage with things differently and to expand ideas.

—Kathleen Howe

Director of the Pomona College Museum of Art

Read more Oxtoby memories.

The central theme of the Daring Minds Campaign that was launched in 2010 and completed in 2015 was condensed into one five-word sentence at the start of Oxtoby’s address at the campaign launch: “The world needs daring minds.” Pomona, he said, must be a source for global citizens who possess not only the knowledge and understanding to give them mastery of their field, but also the creativity and intellectual daring necessary to use those resources to make a difference in the world.

Out of that campaign, which raised a total of more than $316 million and changed the face of the College in significant ways, came a series of initiatives designed to challenge students to create something new or to pit their knowledge and problem-solving skills against problems in the real world. For instance, Pomona’s new Studio Art Building provides a state-of-the-art facility for the creation of art in an inspiring and rigorous setting, while the new Intensive Summer Experience program expands opportunities for students to spend a summer in research or an internship and provides funding to ensure that all students, including those whose families depend upon their summer earnings, can afford to take part.

But perhaps the most inventive expression of Oxtoby’s focus on nurturing daring minds came at the close of the Daring Minds Campaign, with the creation of The Rick and Susan Sontag Center for Collaborative Creativity. Though housed at Pomona, this innovative new program—designed to give students a setting in which they can hone their creative ability by combining their knowledge, energy and creativity with those of other students and faculty to take on complex, real-world problems that require collaboration across disciplines and innovative thinking—also reflected Oxtoby’s longtime commitment to collaborating more closely with the other institutions of the Claremont consortium. Conceived from the beginning as a 5-college endeavor, today the Sontag Center brings together students from across the five undergraduate colleges of The Claremont Colleges to stretch their creative muscles in productive and instructive ways.

As Oxtoby wrote last year at the campaign’s close: “Our goal is much greater than the accumulation of knowledge—it is the creative use of knowledge and the discovery of new knowledge. We foster wide-vista thinking and doing. Pomona is a place where daring minds thrive both in and out of the classroom as they strive to make the world safer, healthier, more understandable, more beautiful, and more just.”

MORE:

36 Hours in the Life of a President

The Oxtoby Years

Oxtoby Scrapbook

2. California sycamore (Platanus racemosa)*

2. California sycamore (Platanus racemosa)*

4. Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)*

4. Coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens)*

6. Mesa oak (Quercus englemannii)*

6. Mesa oak (Quercus englemannii)*

8. Canary Island palm (Phoenix canariensis)

8. Canary Island palm (Phoenix canariensis)

10. Sweetshade Hymenosporum flavum)

10. Sweetshade Hymenosporum flavum)

Moab, Utah by Day & Night

Moab, Utah by Day & Night Walking with Alzheimer’s:

Walking with Alzheimer’s: The Fog Seller

The Fog Seller Rosa’s Very Big Job

Rosa’s Very Big Job The Legacy of the Moral Tale:

The Legacy of the Moral Tale: Alphabet Fun:

Alphabet Fun: Preparing to Teach Social Studies for Social Justice:

Preparing to Teach Social Studies for Social Justice: Peak Performance:

Peak Performance:

Silver / The Liberal Arts

Silver / The Liberal Arts Carbon / Sustainability

Carbon / Sustainability The Halogens / Diversity

The Halogens / Diversity Nearly 14 years ago I wrote a column about the imminent departure of Pomona’s eighth president. It began with these words: “A college president is remembered for a word, a deed, a gesture—something personal to each one of us. A presidency, however, is remembered for more enduring things.”

Nearly 14 years ago I wrote a column about the imminent departure of Pomona’s eighth president. It began with these words: “A college president is remembered for a word, a deed, a gesture—something personal to each one of us. A presidency, however, is remembered for more enduring things.” When Amy Watt ’20 got the call that she would be traveling to Rio de Janeiro in early September, her joy in making the U.S. Paralympic track and field team was tempered by worry about missing the first two weeks or so of her first semester at Pomona. She remembers calling Pomona-Pitzer Women’s Cross-Country and Track & Field Coach Kirk Reynolds with trepidation.

When Amy Watt ’20 got the call that she would be traveling to Rio de Janeiro in early September, her joy in making the U.S. Paralympic track and field team was tempered by worry about missing the first two weeks or so of her first semester at Pomona. She remembers calling Pomona-Pitzer Women’s Cross-Country and Track & Field Coach Kirk Reynolds with trepidation. This is not how most of us think of Pomona’s third and perhaps best known president, James A. Blaisdell, but like the rest of us, he was once a child, and unlike most of us, he had his likeness recorded at the age of about six in the form of a plaster bust.

This is not how most of us think of Pomona’s third and perhaps best known president, James A. Blaisdell, but like the rest of us, he was once a child, and unlike most of us, he had his likeness recorded at the age of about six in the form of a plaster bust.