For Ramona Bridges ’77 the descent into homelessness was like falling off a cliff.

FOR RAMONA BRIDGES ’77, the plunge into homelessness was like falling off a cliff. One day, she was a grounded single woman with a solid career, working a stable job. The next, she was an aimless, disoriented street person, pushing her sad belongings in a shopping cart, repeatedly arrested as a trespasser, in and out of jails and mental wards, and even banished from her own church, her only solace in her life’s most desperate moment.

Suddenly, Bridges had lost her job, her home, her car. And she had lost her way in life.

Once the bright star of her Catholic high school in South Los Angeles, one of the few African American students attending Pomona College in the mid-’70s, Bridges had met a dead end in mid-life.

How could it have come to this? How did a young woman with so much promise wind up with nothing to her name except a misdemeanor criminal record, multiple restraining orders and a tarnished résumé?

“I guess I haven’t thought about it because my faith helped me so much when I was homeless,” says Bridges. “If I hadn’t had the religious background that I had, something bad probably would have happened to me out on the streets. I felt like it was a spiritual experience. So no, it didn’t scare me.”

Ramona Armenia Bridges was born in Austin and still has a taste of a Texas drawl. Her father was an accountant, her mother a teacher. She had three siblings, but she always thought of herself as “a mommy’s girl, her favorite child, probably.” She was a tomboy when it came to sports, but she treasured the dresses her mother would sew for her at Easter.

Her parents divorced when Bridges was 13, and the teenager moved with her mother to Los Angeles. She remembers it as “a happy move,” hitching a U-Haul and heading west with her uncle and cousin. The year was 1969, the start of a new life.

The newcomers moved into an apartment in the Fairfax district. They were one of the few African-American families in the neighborhood, she recalls. But Bridges didn’t attend Fairfax High, the public school across the street. Instead, she enrolled in an all-girls Catholic school, the now-defunct Regina Caeli, 25 miles away in the heart of Compton. Her mother made the daily drive to drop her off and pick her up.

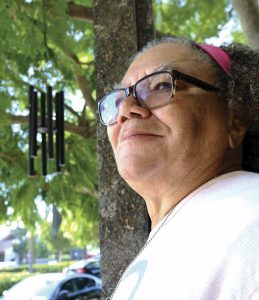

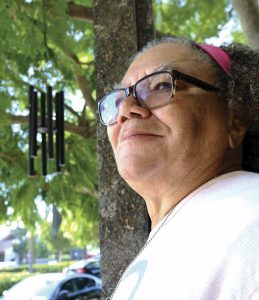

Ramona Bridges ’77 revisits a bench beneath which she sometimes slept during the time that she was homeless.

The extra effort paid off. The school’s 1973 yearbook documents the graduate’s stellar record: student body president, National Honor Society, glee club, French club, and varsity basketball. Her fellow students also voted her “Most Typical,” an ambiguous title that, as she explains it now, may as well have been “Miss Goody Two-Shoes.”

“I was always doing what I was told to do,” said Bridges, who speaks with a slight lisp that she attributes to sucking her thumb as a child. “A lot of times I got criticized for not doing the popular things, because you know how girls are. They want you to chase the boys and all that. And I just wasn’t going to necessarily do all that. You know, I was going to do the right thing. So I didn’t win any popularity contests. But the nuns loved me.”

Back then, Bridges didn’t dwell on what the future might hold.

“You know, you’re young and you don’t really have anything in mind,” she says. “I knew I was going to college. That was a given, because my mother made a house rule that everybody was going to college. No exceptions.”

Pomona College recruiters came on campus and “made a good pitch,” she recalls. They were looking for “somebody from the inner city that had scholarship credentials,” and she fit the bill. Bridges enrolled with vague ambitions to be a doctor, though she quickly decided “that I couldn’t cut the mustard” in premed. So she switched majors to psychology, “which was more my forté.”

Bridges also came out in college as a lesbian, though it wasn’t a crisis for her. “No, it might have been a crisis for my mom,” she says, with a smile. “It blew her mind. But it wasn’t for me, no.”

At the time, she thought her psychology degree would lead to “some kind of job” in counseling or social services. But after graduation, the only job she could find was in the insurance business.

For the next 15 years, Bridges toiled anonymously in unglamorous insurance work, first as a claims adjustor with State Farm in Oregon, then back in L.A. with the California Department of Insurance, this time handling consumer complaints.

It was steady work for more than a decade, but not exactly fulfilling. So Bridges started working for nonprofits, sometimes as second jobs. She was a youth advocate, children’s social worker and caregiver. Then in 2001, she was hired by the California State Employment Development Department (EDD), helping people file unemployment claims.

She held that job for almost 12 years, until a crisis within the agency led to a personal crisis for Bridges. Stress at work, she says, triggered the mental illness that had haunted her since her 30s. Suddenly, she found herself on the downward spiral into homelessness.

Bridges remembers finding comfort on a bench outside her church, the Agape International Spiritual Center, where she could listen to the wind chimes.

Bridges was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in the 1990s. She had gone through a bitter breakup with her long-term partner and the loss of their Lancaster home through foreclosure. At the same time, she discovered that her younger brother, now deceased, was HIV-positive.

“So that all made me snap,” says Bridges, who was prescribed medication to control her mood swings.

Fast-forward a decade. In 2007, Bridges was working two jobs—by day at the EDD and by night as a live-in caretaker for a disabled adult. But by 2011, she felt burned out. She wanted privacy and a place of her own. So she quit the night job and moved into a one-bedroom apartment in Inglewood, where the rent chewed up half her pay. “It wasn’t the smartest thing to do because I couldn’t support myself on one income,” she says.

The breaking point came in 2013. The EDD was under pressure to clear a backlog of old cases, forcing employees to work faster. Bridges resisted the rush and argued that clients needed better service, which takes time. “Well, they started making my life miserable,” she says. “And I got thrown under the bus as a result of speaking out the way I did.”

Once again, stress triggered her bipolar symptoms.

“What happens is—when I start getting manic, I don’t sleep enough, and that’s what brings on the sickness. So I started staying up all hours of the night.”

Bridges says she went out on disability, under doctor’s orders. What she did next—or failed to do—would prove catastrophic.

Bridges missed the deadline to file for disability benefits, a lapse that would delay her checks. Now, with no income, she stopped paying her rent. Then she stopped taking her meds and started acting out. Neighbors called police. An eviction notice was tacked to her front door.

Before she knew it, she was out on the street.

Bridges is very good at giving directions. She navigated for her mother with maps as they drove around an unfamiliar L.A. Today, she knows these streets like a cabbie. In fact, she worked for a time as an Uber driver in 2012, and also as a chauffeur for celebrities, once even attending the Oscars.

Recently, she led a reporter on a tour of her favorite homeless haunts, mainly in West L.A., near the Howard Hughes Center. There was the bench at a bus stop and, when she could afford it, the hotel across the street, until they kicked her out. Nearby, she staked out a special spot outside her church, the Agape International Spiritual Center, sleeping on a bench, wind chimes ringing softly in the cool ocean breeze. She found peace and comfort here. But that wouldn’t last either.

Court records show Bridges faced multiple criminal charges for trespassing. But when asked about her specific behavior, she answered only vaguely. “I’m trying to remember what would I do,” she says. “I would behave in a strange way where people would think something was wrong.”

Indeed, at times she was so disruptive during church services that police were called. Once, she got into a physical altercation with a church security guard who, according to police reports, held her on the ground with a knee in her back. She was taken to a psych ward and banned from the church.

Looking back, Bridges says police and prison guards treated her “like a second-class citizen.” She doesn’t remember ever being aggressive, but police and church officials tell a different story. They say a barefoot Bridges was often angry and delusional, lashing out at strangers. In one report, officers describe her as “yelling incoherently and (being) verbally aggressive.”

At one point, Bridges sought counseling from a church minister, the Rev. Greta Sesheta. Bridges brought an expensive bottle of wine and asked the minister to give it to Oprah Winfrey, who she said was her friend and an inspiration. The pastor could see that Bridges was in a lot of pain. What she needed was just someone to talk to her, to listen and to offer encouragement.

“I admired her in a way,” says Sesheta, “because she was having such difficulties, yet she always had a higher vision for her life. She always had these great ideas for businesses that she could start. The spirit within her was strong.”

Bridges was soon allowed back in the church, and the minister has been impressed with her recovery.

“Now she seems completely self-sufficient,” Sesheta says. “It’s almost like talking to a completely different person.”

Back among familiy and friends, Bridges is joined by her cousin and fellow church member Jason Mitchel (right) and Thelma Chichester, chief administrative officer at Agape.

Eventually, Bridges had a life-saving payday. Her disability came through, and so did a settlement for a separate workers’ compensation claim, which she says she had to sue to win. The money helped her get off the streets, and her restored health insurance helped her gain stability, because she was able to start taking her meds regularly again.

Bridges also credits the help of loyal friends like Audrey James, who visited her in jail and bought her clothes. Then there were her best friends—books. They were like medicine without a prescription. The “healing messages” contained in them, she says, helped “me find my way back to myself.”

Still, it wasn’t easy getting an apartment with an eviction on her credit record. So in 2014 Bridges rented a room that she found advertised on a bulletin board at a Starbucks on La Brea in Inglewood. She lived there for the next two years, until a family crisis called her back to Texas.

When Bridges was homeless she had had a falling-out with her mother, who at one point refused to bail her out of jail. “My mother was very disappointed that I had gotten arrested and was homeless,” she says, “so she lost a lot of respect for me.” Now, the elderly woman was ailing. She had moved back to Texas and was calling for her once-favored daughter. “She was lonely and didn’t want to live by herself,” recalls Bridges. So just before Christmas in 2016, she returned to the Lone Star State to be with her mother.

Three months later, her mother was dead at 87.

Today, Bridges is back in Los Angeles, living with her aunt and looking for work again. Finding a job is still a struggle. In December, she had passed on one job offer from a homeless agency because of her move. “Trust me, I was disappointed, because it had taken me forever to get that job,” she says, over her favorite chicken wrap sandwich at that same Starbucks. “I always wanted to be at work. But because I’m 62 and I haven’t worked in three or four years, those are overall barriers to my employment.”

Asked for a copy of her current résumé, Bridges makes a dash to retrieve one from her car, a Toyota Rav 4 purchased when her disability came through. She always keeps her phone close, anxiously anticipating word of any new job offer.

The tough time on the streets had taken its toll physically; she has missing teeth, “really bad knees,” chronically aching feet and diabetic nerve damage. Luckily, she was able to get her Kaiser health insurance coverage back as part of her pension benefits. These days, she’s careful to take her meds every night before bedtime, for her cholesterol, blood pressure and bipolar disorder.

Bridges is trying to rebuild her life and her image. She has written a book about her homeless experience, slyly titled Forgive Me My Trespasses. And she has a website (ramonabuildsbridges.com) putting herself forward as an educator, mental health advocate and speaker on homelessness and women’s empowerment. She also makes a pitch for donations to complete a documentary and to join her campaign to end homelessness, Ramona’s Bridge, granting donors such benefits as “VIP seating” at her book signings.

“When I got out, I wanted to start an advocacy group,” she says, “because I didn’t want to see this happen to anybody else.”

And she vows it will never happen to her again.

In late September of this year, Bridges still had irons in the fire. She had gone through a background check to work for FEMA at a Pasadena call center for hurricane relief. But she worried she wouldn’t pass the credit check required for federal employees because her credit was “in the toilet.” She also applied to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority to work on the county agency’s emergency response team.

Yes, the search has been frustrating. But through it all, there’s one thing she hasn’t lost—her faith. And that gives her hope that she’ll finally find work again.

“I pray on it,” she says softly. “I pray on it.”

Susan McWilliams doesn’t mince words when it comes to predicting the future of the American Experiment.

Susan McWilliams doesn’t mince words when it comes to predicting the future of the American Experiment. Japan may be the economic canary in the coal mine, Matt Sanders ’00 believes. And at the same time, it may already be transforming itself into the economy of tomorrow.

Japan may be the economic canary in the coal mine, Matt Sanders ’00 believes. And at the same time, it may already be transforming itself into the economy of tomorrow. With the July 1 election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (widely known by his initials, AMLO) as president, Mexico stands at a historic turning point, one that leaves Professor of Latin American Studies Miguel Tinker Salas cautiously optimistic about the prospect for real change.

With the July 1 election of Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (widely known by his initials, AMLO) as president, Mexico stands at a historic turning point, one that leaves Professor of Latin American Studies Miguel Tinker Salas cautiously optimistic about the prospect for real change. Predicting the future in a conflict as multi-faceted as the Syrian Civil War is daunting, and Politics Professor Mietek Boduszynski says his thoughts on the matter have shifted several times, including last May, when the United States pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal.

Predicting the future in a conflict as multi-faceted as the Syrian Civil War is daunting, and Politics Professor Mietek Boduszynski says his thoughts on the matter have shifted several times, including last May, when the United States pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal. Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold.

Where in the world will the next revolution happen? And what will it look like? These are questions Associate Professor of Sociology Colin Beck thinks about a lot. The author of Radicals, Revolutionaries and Terrorists is now at work with five other scholars on a new book titled Rethinking Revolutions, and last fall, three of his coauthors joined him at Pomona for a panel session called “The Future of Revolutions.” As part of that event, Beck asked each of them to make a prediction as to where the next revolution will unfold. The Wolf, the Duck, and the Mouse

The Wolf, the Duck, and the Mouse Return

Return Displaying Time: The Many Temporalities of the Festival of India

Displaying Time: The Many Temporalities of the Festival of India Come As You Are

Come As You Are Roadside Geology of Southern California

Roadside Geology of Southern California The Silly Parade and Other Topsy-Turvy Poems

The Silly Parade and Other Topsy-Turvy Poems Real Deceptions: The Contemporary Reinvention of Realism

Real Deceptions: The Contemporary Reinvention of Realism Money Machine: The Surprisingly Simple Power of Value Investing

Money Machine: The Surprisingly Simple Power of Value Investing Camille Molas ’21 begins her first year at Pomona College in uniquely Southern California fashion, with surfing lessons at Mondo’s Beach in Ventura. Again this year, as part of New Student Orientation, the Orientation Adventure program, usually known simply as “OA,” offered a list of 11 outdoor opportunities across California, ranging from hiking to surfing, rock climbing to volunteerism. “What I’m really excited about,” Molas says, “is continuing to build the relationships we made at OA. You know, it’s really different having your first moments together out here on the beach or out here camping. If we can be there for each other out in the outdoors, we can be there for each other when school comes around.”

Camille Molas ’21 begins her first year at Pomona College in uniquely Southern California fashion, with surfing lessons at Mondo’s Beach in Ventura. Again this year, as part of New Student Orientation, the Orientation Adventure program, usually known simply as “OA,” offered a list of 11 outdoor opportunities across California, ranging from hiking to surfing, rock climbing to volunteerism. “What I’m really excited about,” Molas says, “is continuing to build the relationships we made at OA. You know, it’s really different having your first moments together out here on the beach or out here camping. If we can be there for each other out in the outdoors, we can be there for each other when school comes around.” Pomona College is expanding the Claremont Hills Wilderness Park with a gift of 463 acres to the city of Claremont. The land, including Evey Canyon and three Padua Hills parcels, is to be preserved in its undeveloped state and remain available to the members of the public for hiking, biking, horseback riding and other passive recreational uses. With the new addition, the size of the park will increase to nearly 2,500 acres.

Pomona College is expanding the Claremont Hills Wilderness Park with a gift of 463 acres to the city of Claremont. The land, including Evey Canyon and three Padua Hills parcels, is to be preserved in its undeveloped state and remain available to the members of the public for hiking, biking, horseback riding and other passive recreational uses. With the new addition, the size of the park will increase to nearly 2,500 acres.