In its first year, Pomona’s Humanities Studio will take as its inaugural theme a line from Samuel Beckett, “Fail Better,” according to its founding director, Kevin Dettmar, the W.M. Keck Professor of English.

Each year the program will bring together a select group of faculty, postdoctoral and student fellows in the humanities for a year of engaged intellectual discussion and research on interdisciplinary topics of scholarly and public interest. Programming will also include visiting speakers, professional development workshops and other community events.

Dettmar said the theme honors the late Arden Reed, professor of English, who spoke on the topic last year. Reed’s career, Dettmar notes, “was anything but a failure. But we will honor his memory by applying ourselves to the twin concepts of failure and its kissing cousin, error—seeking better to understand the uses of failure and the importance of error in the ecosystem of scholarly discovery. Together with the studio director, faculty and postdoctoral fellows, and a group of visiting speakers, writers and thinkers, Humanities Studio undergraduate fellows will take a deep dive into failure, to bring back the treasures only it has to offer.”

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era.

Pomona professors Jerome D. Laudermilk and Philip A. Munz made headlines after traveling to the Grand Canyon to study a rare find: 20,000-year-old giant-sloth dung. According to an article in the Sept. 20, 1937, issue of Life magazine, the dung covered the floor of a cave believed to be home to giant ground sloths, which waddled on two legs and could grow as large as elephants. Laudermilk and Munz hoped to uncover the sloths’ diet and what it might reveal about plant and climate conditions of the era. As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant.

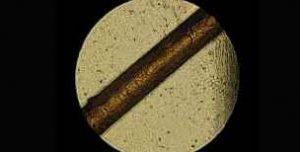

As a Pomona student, the late Lee Potter ’38 had a simple plan to pay his way through college: sell his skills embalming animals. Potter, a pre-med student, had more than four years of embalming experience by the time the LA Times profiled him on June 1, 1937. He embalmed fish, frogs, rats, earthworms, crayfish and sharks and sold them to schools for anatomical study in their labs. His best seller: sharks—once, he sent an order of 200 embalmed sharks to a nearby college. His ultimate goal was to embalm an elephant. In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.

In August 1936, a Riverside woman named Ruth Muir was found brutally murdered in the San Diego woods, and the case ignited a media frenzy. A suspect claiming he “knows plenty” about Muir’s murder was found with 20 hairs that appeared to belong to a woman. In their rush to test whether the hairs were Muir’s, police turned to an unlikely source to conduct the analysis—Pomona College. Though the hairs do not seem to have matched Muir’s in the end, at least we can say: For a brief moment, Pomona operated a crime lab.

Camille Molas ’21 begins her first year at Pomona College in uniquely Southern California fashion, with surfing lessons at Mondo’s Beach in Ventura. Again this year, as part of New Student Orientation, the Orientation Adventure program, usually known simply as “OA,” offered a list of 11 outdoor opportunities across California, ranging from hiking to surfing, rock climbing to volunteerism. “What I’m really excited about,” Molas says, “is continuing to build the relationships we made at OA. You know, it’s really different having your first moments together out here on the beach or out here camping. If we can be there for each other out in the outdoors, we can be there for each other when school comes around.”

Camille Molas ’21 begins her first year at Pomona College in uniquely Southern California fashion, with surfing lessons at Mondo’s Beach in Ventura. Again this year, as part of New Student Orientation, the Orientation Adventure program, usually known simply as “OA,” offered a list of 11 outdoor opportunities across California, ranging from hiking to surfing, rock climbing to volunteerism. “What I’m really excited about,” Molas says, “is continuing to build the relationships we made at OA. You know, it’s really different having your first moments together out here on the beach or out here camping. If we can be there for each other out in the outdoors, we can be there for each other when school comes around.” Pomona College is expanding the Claremont Hills Wilderness Park with a gift of 463 acres to the city of Claremont. The land, including Evey Canyon and three Padua Hills parcels, is to be preserved in its undeveloped state and remain available to the members of the public for hiking, biking, horseback riding and other passive recreational uses. With the new addition, the size of the park will increase to nearly 2,500 acres.

Pomona College is expanding the Claremont Hills Wilderness Park with a gift of 463 acres to the city of Claremont. The land, including Evey Canyon and three Padua Hills parcels, is to be preserved in its undeveloped state and remain available to the members of the public for hiking, biking, horseback riding and other passive recreational uses. With the new addition, the size of the park will increase to nearly 2,500 acres. Starting at about 1 a.m. on June 5, Renwick House took a quick trip to its new home on the opposite side of College Avenue, making room for the construction of the new Pomona College Museum of Art. Renwick, which was built in 1900, is now the third stately home on College to have been moved from its original location, joining Sumner House and Seaver House, both of which were moved to Claremont from Pomona. The three-hour Renwick move, however, pales in comparison to the difficulty of the other two. The Sumner move took six weeks in 1901, using rollers drawn by horses. The 10-mile Seaver move, in 1979, took 20 hours.

Starting at about 1 a.m. on June 5, Renwick House took a quick trip to its new home on the opposite side of College Avenue, making room for the construction of the new Pomona College Museum of Art. Renwick, which was built in 1900, is now the third stately home on College to have been moved from its original location, joining Sumner House and Seaver House, both of which were moved to Claremont from Pomona. The three-hour Renwick move, however, pales in comparison to the difficulty of the other two. The Sumner move took six weeks in 1901, using rollers drawn by horses. The 10-mile Seaver move, in 1979, took 20 hours.

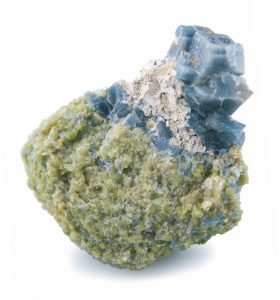

Deep in the bowels of the Geology Department in Edmunds Hall is a room full of storage cabinets with wide, shallow drawers filled with mineral specimens collected by Pomona geologists over the years. Many of them, according to Associate Professor of Geology Jade Star Lackey, go all the way back to the department’s founder, Alfred O. “Woody” Woodford 1913, who joined the chemistry faculty in 1915, launched the geology program in 1922 and served as its head for many years before retiring some 40 years later. Many of Woodford’s carefully labeled specimens came from the Crestmore cement quarries near Riverside, Calif. “Woody even had a mineral named after him for a while,” Lackey says, but the mineral was later found to have already been discovered and named. “More than 100 different minerals were discovered at Crestmore, including some striking blue-colored calcites—echoes of Pomona.” Ultimately, Lackey adds, Crestmore was quarried to make the cement to construct the roads and buildings of Los Angeles, but in the meantime, “Woodford trained many a student there, and the mineral legacy of Crestmore is widely known.”

Deep in the bowels of the Geology Department in Edmunds Hall is a room full of storage cabinets with wide, shallow drawers filled with mineral specimens collected by Pomona geologists over the years. Many of them, according to Associate Professor of Geology Jade Star Lackey, go all the way back to the department’s founder, Alfred O. “Woody” Woodford 1913, who joined the chemistry faculty in 1915, launched the geology program in 1922 and served as its head for many years before retiring some 40 years later. Many of Woodford’s carefully labeled specimens came from the Crestmore cement quarries near Riverside, Calif. “Woody even had a mineral named after him for a while,” Lackey says, but the mineral was later found to have already been discovered and named. “More than 100 different minerals were discovered at Crestmore, including some striking blue-colored calcites—echoes of Pomona.” Ultimately, Lackey adds, Crestmore was quarried to make the cement to construct the roads and buildings of Los Angeles, but in the meantime, “Woodford trained many a student there, and the mineral legacy of Crestmore is widely known.”