There was a time when editorial cartooning was a job a young artist could aspire to. In 1900, there were an estimated 2,000 editorial cartoonists at work in the United States. They still numbered in the hundreds by the late ’70s, when—at the start of my career—I briefly became one of them.

There was a time when editorial cartooning was a job a young artist could aspire to. In 1900, there were an estimated 2,000 editorial cartoonists at work in the United States. They still numbered in the hundreds by the late ’70s, when—at the start of my career—I briefly became one of them.

It’s probably just as well that I moved on to other things. Since then, the American editorial cartoonist has become an endangered species, right up there with the pygmy elephant. The total in the U.S. is reportedly below 25 now, and falling. Just in the last two years, two Pulitzer Prize-winners—Nick Anderson at the Houston Chronicle and Steve Benson at the Arizona Republic—were dumped. In June, following an uproar about a cartoon full of anti-Semitic tropes, the international edition of The New York Times followed the example of its national counterpart and fired its last two cartoonists—neither of whom, by the way, had drawn the offending cartoon.

Here’s how bad it’s gotten: Iran now boasts more editorial cartoonists than the U.S.

I thought for a while that editorial cartooning would be my life’s work. Old-timers like Herblock and Conrad were giving way to subtle, innovative artists like Pat Oliphant and Jeff MacNelly. Strip cartoonists like Doonesbury creator Gary Trudeau were blurring the line between the Sunday comics and the editorial page. These young guns were transforming the medium—putting irony and satire, artistic style and sly visual humor ahead of blunt-force commentary. It was an exciting time to be an editorial cartoonist.

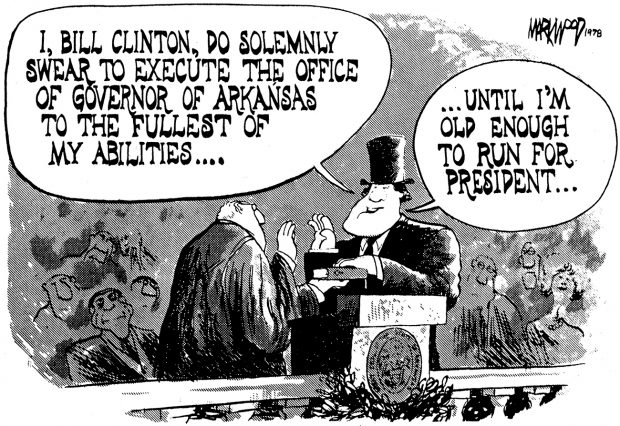

And I loved the actual process of creating a cartoon—the immersion in the news, the joyous flash of inspiration, the inner howls of laughter as I did my preliminary sketches, the knowledge of famous faces that allowed me to draw Ronald Reagan or Bill Clinton without conscious thought and the feeling of working without a net each time I wielded my ink brush to create the final product.

Over the years, I must have done hundreds of drawings of Clinton, then governor of the state where I lived, including one, shown here, that was completed shortly after he was first elected governor at the tender age of 32. It’s without a doubt the most prescient thing I’ve ever produced.

Part of the fun of it was the pure joy of poking fun at powerful people. I used to joke that we editorial cartoonists were the last of the yellow journalists—the only purveyors of the news who still had license to use caricature and exaggeration to distill complicated situations down to a single, simplistic metaphor. Our work was full of open mockery —an artform that intentionally stretched the limits of polite discourse.

And that was probably a big part of its undoing. In a time of heightened sensitivities and social media mobs, caricature has become a dangerous sport. As Australian cartoonist Mark Knight (whose caricatures are uniformly brutal) learned when tennis player Serena Williams’s husband accused him of a racist depiction of her, there’s a fine line between the kind of harsh visual exaggeration that caricatures depend upon and the perpetuation of cruel stereotypes. Add in the decline of newspapers as a profitable industry, and it’s not surprising, I suppose, that cartoonists have become, at best, expendable and, at worst, potential liabilities.

Given all of that, the number of young American artists who now aspire to become the next great editorial cartoonist is probably on a par with the number who plan to repair steam engines. But while the bell is clearly tolling for American editorial cartooning, I have to admit that I was wrong when I said we were the last of the yellow journalists. Yellow journalism, I’m afraid, is viciously alive and well on social media and talk radio—minus, of course, the redeeming humor.

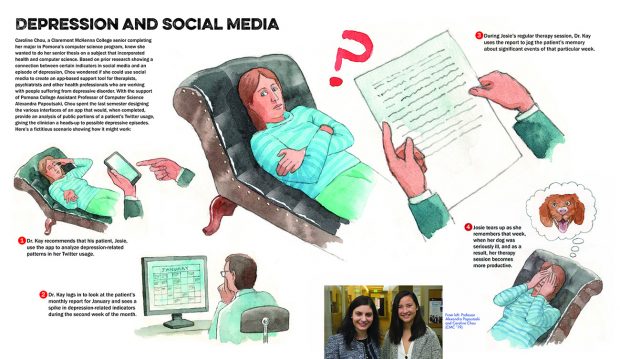

Social Media: Not the Answer

Social Media: Not the Answer The spring/summer issue is a splendid piece of work in all ways, but unfortunately, it contains an error on page 52, line 7 of the Class of ’49 notes. I am a member of the Nature PRINTING Society, not the Nature PAINTING Society. If you will access the

The spring/summer issue is a splendid piece of work in all ways, but unfortunately, it contains an error on page 52, line 7 of the Class of ’49 notes. I am a member of the Nature PRINTING Society, not the Nature PAINTING Society. If you will access the  A Rural Voice

A Rural Voice My favorite anecdote about growing up in the rural South is a childhood memory of sitting with my aunt and uncle at their red Formica kitchen table, which was strategically positioned in front of a double window looking out on the dirt road in front of their house. Each time a car or—more likely—a pickup would go by, leaving its plume of dust hanging in the air, both of them would stop whatever they were doing and crane their necks. Then one of them would offer an offhand comment like: “Looks like Ed and Georgia finally traded in that old Ford of theirs. It’s about time.” Or: “There’s that Johnson fellow who’s logging the Benton place. Wonder if he’s any kin to Dave Johnson.”

My favorite anecdote about growing up in the rural South is a childhood memory of sitting with my aunt and uncle at their red Formica kitchen table, which was strategically positioned in front of a double window looking out on the dirt road in front of their house. Each time a car or—more likely—a pickup would go by, leaving its plume of dust hanging in the air, both of them would stop whatever they were doing and crane their necks. Then one of them would offer an offhand comment like: “Looks like Ed and Georgia finally traded in that old Ford of theirs. It’s about time.” Or: “There’s that Johnson fellow who’s logging the Benton place. Wonder if he’s any kin to Dave Johnson.”

POMONA IS EXTRAORDINARY. We remind ourselves of this proudly when we marvel at the brilliance of our students and faculty, the accomplishments of our alumni, the talent of our staff, the amazing marks Sagehens leave on the world. How many high-achieving people, people who never give up, do we see every day?

POMONA IS EXTRAORDINARY. We remind ourselves of this proudly when we marvel at the brilliance of our students and faculty, the accomplishments of our alumni, the talent of our staff, the amazing marks Sagehens leave on the world. How many high-achieving people, people who never give up, do we see every day?