Severine von Tscharner Fleming ’04 is in the middle of another one of her jam-packed days, and this time it’s literal: stooped over the kitchen sink in Essex, N.Y., she grins and holds out two big buckets of rose hips that she’s about to clean, cube and slow-cook into a marmalade-like jam.

“I love the little pricklies,” she gushes, as she cradles the harsh fuzz of the fruit with her fingertips. She recalls how as a kid she spent summers at her grandmother’s farm in Switzerland, where she climbed trees, milked cows and first fell in love with farm life. Now planted in the rural northern reaches of New York State, she still seems to be in the honeymoon phase when it comes to agriculture, although she has farmed for eight seasons now.

Fleming is drawn to farming’s “alluring mix of sensuality and politics,” which is partly why she’s so concerned about its future. In the last century, the proportion of farmers in the U.S. workforce shrunk from nearly half to less than 2 percent, and the rise of Big Agriculture has come at a cost. “Industrialization, specialization and concentration,” says Fleming, “have created a system which is brittle, highly energy-addicted and whose practices erode the future carrying capacity of the soil.”

Discomforting trends like these have inspired Fleming and others to try to spark a revolution in a farming industry that’s fraying and graying. Through her leadership in groups such as Farm Hack, Agrarian Trust and the National Young Farmers’ Coalition, she has become in many ways the face of a movement of young people who are ready to get their hands dirty. The idea, simply put, is to create a national patchwork of upstart farmers who will grow food to be sold close to market and serve as stewards of the dwindling supply of irrigable farmland.

“We have to catalyze, crystallize and publicize to get folks involved,” Fleming says. “The odds are stacked against us, but at the same time, there’s progress,” says Fleming. “People are stepping up and showing up.”

It’s not just a smattering of urban gardeners and hippies who are concerned. U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack set a goal of creating 100,000 new farmers in the next few years. Congress launched the National Institute of Food and Agriculture to speed up the pace of scientific discovery in the field. And authors like Michael Pollan have advocated expanding training programs for U.S. farmers—“not as a matter of nostalgia for the agrarian past,” as he wrote in a 2008 New York Times op-ed, “but as a matter of national security.”

Hope may lie with Fleming’s fellow Millennials—though your typical farmer these days skews more AARP than Generation Y. According to the USDA’s 2007 agricultural census, since 1978 the average age in the profession has increased seven years, from 50 to 57. Farmers who are 65 and older outnumber those 35 and younger by a factor of six to one.

The aging in agriculture wasn’t entirely unexpected. A whole generation essentially opted out of the industry as a result of the ’80s farm crisis, when the U.S. lost approximately 300,000 farms due to high interest rates and an unfavorable economic climate. “Those kids [growing up then] looked at their parents’ lives and the stress of expensive land and mountains of debt,” Fleming says, “and they simply weren’t inspired to jump in … for good reason.”

She is cautiously optimistic that the tide may be turning, expecting that the number of young farmers will be on the rise when new figures are released next year. Fleming says that her generation is unlike any before them—an army of entrepreneurial-minded, educated, first-time farmers with a passion for local food and an eagerness to employ sustainable methods.

Rather than cultivating large acreage of a single crop in a monoculture and selling it to middlemen in the commodity market, this niche of farmers sells a wide variety of goods, often directly to the public through markets and community-supported agriculture programs. Capturing the retail price is a critical element for their success, Fleming says. In the last 15 years, revenue from this farm-to-table model has more than doubled in the U.S., and it’s what helps folks like Fleming stand out and survive in a David-and-Goliath marketplace.

“Out of both preference and necessity, we aren’t doing things like they’ve been done,” Fleming says. “We don’t buy into the idea that we have to be part of this larger machine.”

EVEN AS SHE LEADS the movement, Fleming is not really a “farmer” in the traditional sense. She is actively engaged in the production of food, running a pickle company in the Grange Hall of her town, and making a small line of dried herbs, jellies and wildcrafted teas. But mostly she sits at the computer and talks on the phone, coordinating her grassroots media network.

EVEN AS SHE LEADS the movement, Fleming is not really a “farmer” in the traditional sense. She is actively engaged in the production of food, running a pickle company in the Grange Hall of her town, and making a small line of dried herbs, jellies and wildcrafted teas. But mostly she sits at the computer and talks on the phone, coordinating her grassroots media network.

She hosts a weekly podcast, manages several blogs, and lives in a house bordering Lake Champlain with a vegetable garden and lightning-fast Wi-Fi.

In the last six years, the self-described “punky grassroots farming ninja” has visited 44 states, organizing film screenings, moderating panels and speaking at conferences.

“My mix of farming and activism has been an ever-shifting vinaigrette, and right now I think the best use of my time is being an advocate for the larger cause,” she says. “I don’t mean to shoot holes in your American Gothic storyline, but I don’t live on a farm with pigs and a pitchfork.”

Although, she adds, “last year’s pigs are here, on the porch in the freezer.”

A lanky, frizzy-haired ball of energy who laughs easily, smiles widely and favors flannel, Fleming is constantly in motion and talking effusively about her latest projects, whether that’s a Kickstarter-funded sail freight project that ships pickled goods to yuppies in New York City or an agrarian-themed singles’ mixer dubbed “Weed Dating.”

These days, most of her attention is devoted to the Greenhorns, a 13,000-strong organization she founded that’s aimed at recruiting, promoting and supporting young farmers. The mixers, bonfires and festivals Fleming helps coordinate bring together what she calls the “young farmer tribe.” Add to that almost 30 events for Farm Hack, an initiative that connects engineers and farmers to design open-source farm technologies.

Among her latest Greenhorns activities, she recently finished editing The New Farmers’ Almanac, a sprawling compendium of essays, illustrations and advice from more than 120 contributors. And in January she launched Agrarian Trust, an advocacy project hosted by the Schumacher Center for New Economics, focused on the issue of land access, providing farmers with legal templates and case models.

“She has an infectious enthusiasm and an uncompromising vision where she’ll just move forward on all these projects and expect you to keep up,” says Dorn Cox, board president of Farm Hack. “As long as I’ve known her, she’s always juggled many things at once and done whatever it takes—delegates, cajoles, prods —to make them happen.”

FLEMING AND I ARE standing in a field in Keeseville, N.Y, surrounded by more than 600 revelers that span farmgirls in overalls, hippies with tie-dyed shirts and hipsters without any shirts at all. We are at the fourth-annual Crowfest, a celebration of local agriculture that this year also marks the unofficial debut of her other other venture, Grange Copackers Co-Op, which produces non-perishables ranging from hot sauce to sauerkraut.

Stationed at her stand with a blue sign hand-painted by her brother, Reynolds “Charlie” Fleming PI ’13, Severine is passing out samples of pickled veggies, making small talk and refusing payment: thanks to the tightly-regulated bureaucracy of New York agricultural law, her new business is currently prohibited from accepting money for goods. “Today’s just about meeting strangers and getting our name out,” she says.

Nearby Lucas Christenson, owner of the Fledging Crow Farm that hosts this festival, soaks in the scene and marvels at the fact that only five years ago he was living here in a tent without power or running water.

“There’s definitely a tight-knit community of us,” he says, before motioning over to a group of young farmers congregated around a fire-pit cooking a portly grass-fed pig. “We’re all friends, and we want to do more to cooperate and collaborate.”

Given their busy schedules, that’s not always an easy task, but Fleming views these events as essential for establishing a support system for young farmers.

“The first few years can be so challenging. Many of us feel socially isolated and are struggling to make ends meet,” she says. “It’s important to provide a space where people can go and see that there are others ‘like me’ and support one another.”

FLEMING EMBARKED on one of her earliest community-building initiatives her first year at Pomona, when she led a team of guerrilla gardeners to start the Organic Farm—a project initially marked by wrangling with college officials, but which is now formally included in Pomona’s curriculum. A third-generation Sagehen, Severine is the daughter of noted urban planner and preservation advocate Ronald Lee Fleming ’63.

After two years in Claremont, she took a leave of absence and bought a round-the-world plane ticket to apprentice on farms across the globe, from Australia to South Africa to Scotland. Those experiences made her increasingly aware of—and outraged by—the practices of Big Agriculture, inspiring her to transfer to UC Berkeley, where she graduated with a B.S. in conservation and agro-ecology.

Her real education, however, came from organizing outside the classroom: lectures, workshops and film festivals, which left her struck by “all the dismal horror movies about hunger and soil erosion.” That’s when she decided to focus on solutions.

After graduation, she spent nearly three years traveling the States interviewing young farmers for a more “glass half-full” documentary that became Greenhorns, which has been screened at more than 1,300 schools, conferences and colleges worldwide.

The film was the catalyst that spurred Fleming’s earliest forays in activism, including stints working with the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition to lobby for young farmerfriendly legislation in Washington, D.C. She soon realized through Greenhorns —and the organization of the same name that it spawned—that she could create change by telling stories and connecting people, rather than by having to “put on nice clothes and fly down to the Capitol all the time.”

FAR FROM D.C., as we speed through the winding country roads of rural New York on the way to Crowfest, Fleming points out several abandoned properties along the route, including a dramatically dilapidated barn with a roof that’s completely caved in. “This is what happens when people give up on farming,” she says.

She got her first reality check of this sort right after Berkeley, when she would cruise around Hudson Valley searching for affordable farmland and see unused spaces like these in every town.

“There are very few policy structures to support these places being properly farmed,” she says, “and that needs to change.”A report Fleming co-led through the National Young Farmers Coalition found that the biggest obstacles for aspiring farmers are a lack of access to land, capital and credit. One reason for this is corporate consolidation, spurred by 20th-century technology that has allowed farm operators to harvest more crops on larger amounts of land using fewer people. The growth of these “McFarms” has made it harder than ever for younger farmers to purchase land.

At the same time, farm values have doubled since 2000—good news for existing landowners who need to cash out their land in order to retire, but not for those just starting out. It’s telling that Fleming, a major land access advocate who has farmed for nearly a decade, doesn’t even own her own property in Essex.

“Farmland is becoming an investment asset, where it’s more expensive than is justified by what it can produce,” she says, her voice rising. “It’s no longer about managing a diverse set of crops to support your family.”

Fleming’s anger is understandable, and she notes that her critique is shared by many. Partisan bickering in Congress has repeatedly resulted in watered-down farm bills, and it can be easy to lose hope when so many other issues seem to be capturing the country’s attention (and tax dollars).

But ultimately, she’s hopeful. Initiatives like the USDA’s Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program have established government loans to help new farmers buy land. And, in a larger sense, these organizations’ success with community-building has affirmed Fleming’s belief in the importance of cultivating the “culture” part of “agriculture.”

“In the next 20 years, the amount of land predicted to change hands is 400 million acres, which is roughly the size of the Louisiana Purchase,” she says. “We have an exciting opportunity to change how that land will be managed, but we don’t have much time to do it. We’ve got to get people on board.”

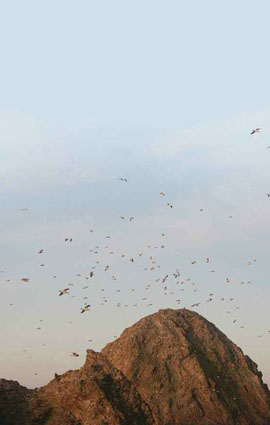

Home to the largest seabird colony in the continental U.S., the Farallones are a magnet for ocean wildlife. In summer, seemingly every inch of the place is claimed by thousands of nesting birds fiercely guarding their chicks. During the winter, noisy elephant seals crowd the beaches to give birth to their pups. Meanwhile, great white sharks hunt in the waters offshore. In other months, blue and humpback whales can be spotted making their annual migrations along the coast. Karnovsky made her first trip to the islands when she was just out of college, to work on a project to record shark sightings.

Home to the largest seabird colony in the continental U.S., the Farallones are a magnet for ocean wildlife. In summer, seemingly every inch of the place is claimed by thousands of nesting birds fiercely guarding their chicks. During the winter, noisy elephant seals crowd the beaches to give birth to their pups. Meanwhile, great white sharks hunt in the waters offshore. In other months, blue and humpback whales can be spotted making their annual migrations along the coast. Karnovsky made her first trip to the islands when she was just out of college, to work on a project to record shark sightings.

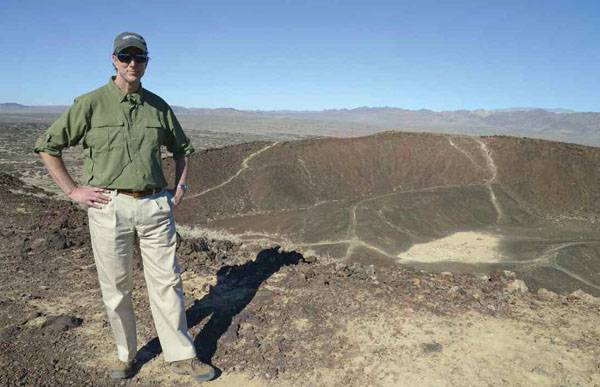

They head down Fish Creek Wash, a dry riverbed winding its way through dramatically deep stone canyons.

They head down Fish Creek Wash, a dry riverbed winding its way through dramatically deep stone canyons. She also is drawn by the juxtaposition. Egrets, ducks and other birds wing above as unseen creatures rustle in the dry grass, a bucolic backdrop to the homeless people sleeping in tents deep in the brush, and the distant rush of commuters barreling down unseen roadways. The air carries a tinge of burning garbage as well, from breakfast campfires near the covered-over Tequesquite Landfill that Williams walked past to get here.

She also is drawn by the juxtaposition. Egrets, ducks and other birds wing above as unseen creatures rustle in the dry grass, a bucolic backdrop to the homeless people sleeping in tents deep in the brush, and the distant rush of commuters barreling down unseen roadways. The air carries a tinge of burning garbage as well, from breakfast campfires near the covered-over Tequesquite Landfill that Williams walked past to get here.

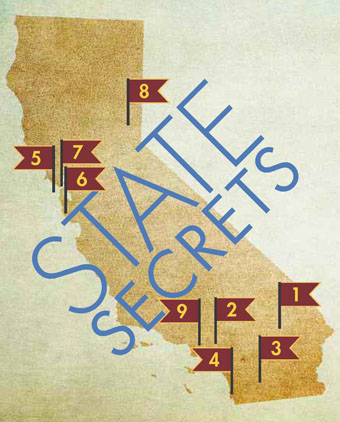

1)

1)

GARFIELD IS AN ACCIDENTAL ENTREPRENEUR. Growing up in suburban Philadelphia, he trained as a classical violinist and was a huge fan of traditional professional sports. Garfield’s slight build limited him to racquet sports, but a video game called Counter-Strike became his competitive outlet. He fell into the role of impresario as a student at Pomona College, when a team of five Canadian friends wanted to go to Dallas for a tournament in 2005 but didn’t have the money. Garfield borrowed $1,000 from his mother to front them, the team finished second and he was on his way. Soon, he was courting sponsors and traveling to tournaments in Italy and Singapore.

GARFIELD IS AN ACCIDENTAL ENTREPRENEUR. Growing up in suburban Philadelphia, he trained as a classical violinist and was a huge fan of traditional professional sports. Garfield’s slight build limited him to racquet sports, but a video game called Counter-Strike became his competitive outlet. He fell into the role of impresario as a student at Pomona College, when a team of five Canadian friends wanted to go to Dallas for a tournament in 2005 but didn’t have the money. Garfield borrowed $1,000 from his mother to front them, the team finished second and he was on his way. Soon, he was courting sponsors and traveling to tournaments in Italy and Singapore.

EVEN AS SHE LEADS the movement, Fleming is not really a “farmer” in the traditional sense. She is actively engaged in the production of food, running a pickle company in the Grange Hall of her town, and making a small line of dried herbs, jellies and wildcrafted teas. But mostly she sits at the computer and talks on the phone, coordinating her grassroots media network.

EVEN AS SHE LEADS the movement, Fleming is not really a “farmer” in the traditional sense. She is actively engaged in the production of food, running a pickle company in the Grange Hall of her town, and making a small line of dried herbs, jellies and wildcrafted teas. But mostly she sits at the computer and talks on the phone, coordinating her grassroots media network.