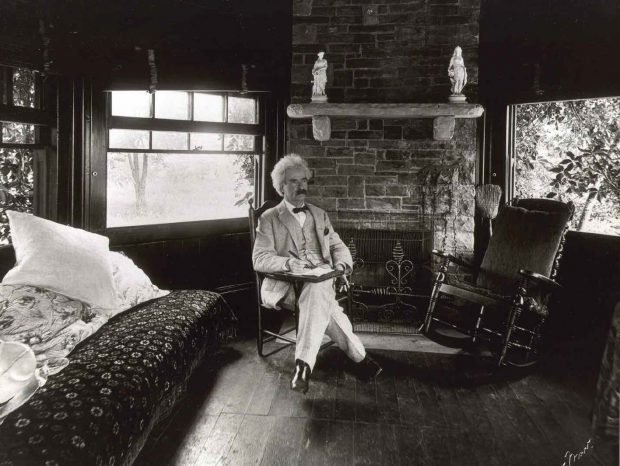

Emily Arnold-Fernández listens to a client’s story at the Asylum Access office in Bangkok, Thailand.

65.3 MILLION

Number of forcibly displaced people around the globe

21.3 MILLION

Total number of refugees worldwide

26 YEARS

Average time a refugee spends in exile, based on the average duration of the 32 protracted refugee situations

0.5%

Percentage of refugees accepted each year into resettlement programs

24

Number of people displaced from their homes every minute of every day

According to 2015 data from the United Nations Refugee Agency

BEFORE THE SYRIAN refugee crisis made headlines, Emily Arnold-Fernández ’99 would ask people, “What do you think is the average time spent in a refugee camp?”

Six months, they’d guess. A year, two years.

In reality, the average time is 17 years.

“We had to do a lot of education so people could understand why we are doing what we are doing,” said Arnold-Fernández, founder of Asylum Access, which empowers and advocates for refugees worldwide. “Now people understand that we’re talking about decades of upheaval.”

She was just back from Thailand, visiting Asylum Access offices and meeting with partners and potential donors. Art from her travels adorned her sunny office in downtown Oakland: a vibrant painting of a woman in a headscarf, painted by a Cairo refugee, and a black-and-white photo of a refugee boy joyously leaping into a river delta in Ecuador.

“Because we’re seeing the greatest number of people displaced since World War II, it feels more urgent,” she said. Refugees living in camps are all but locked up, rarely allowed to leave, while those outside the camps rarely have the right to work, rent an apartment or send their children to school and must do so in the shadows, lacking legal protections.

Assistance to refugees has often come in the form of humanitarian aid—beds and blankets, food and shelter—that address their immediate needs but not long-term goals. Asylum Access is changing that paradigm, helping refugees rebuild their lives by challenging legal barriers.

With 16 offices in the United States, Tanzania, Ecuador, Thailand, Malaysia and Mexico, she’s now expanding her reach by working with organizations in the Middle East and elsewhere to create programs modeled after Asylum Access.

“She’s one of those rare people who can talk to a refugee and sit in a UN council giving testimony,” according to one of her mentors, Kim Nyegaard Meredith, executive director of the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society. “Most people can’t navigate both ends of the continuum.”

The eldest of four children, Arnold-Fernández recalls lively dinnertime conversations with her family about the news. Her parents took her ideas seriously, discussing and debating even her most outlandish childhood proposals. During the California drought in the 1980s, she proposed filling in swimming pools, making them shallow to save water.

At Pomona, she majored in philosophy and music. Her sophomore year, she spent her spring semester in Zimbabwe. Aside from a family car trip to Tijuana and a choir tour to Italy in high school, she’d never traveled abroad. After their orientation, a few weeks spent in a rural village and a crash course in the Shona language, she was told by organizers to navigate her way to the township where she’d live next. Figuring out how left her confident she could go anywhere in the world. Yet her time in Zimbabwe was also humbling.

“I’d always understood myself as someone intelligent and capable, a leader, and all of a sudden I was in a situation where every 5-year old knew how to hand-wash socks in the river and I was the idiot who had to be taught everything from scratch,” she said. She learned firsthand the importance of not making assumptions. “If someone doesn’t speak the language, it doesn’t mean they’re not intelligent.”

After graduating, doing a stint at a domestic violence nonprofit in Los Angeles and teaching English in Spain, she enrolled in law school at Georgetown University. She had a passion for social justice issues, and on a summer internship in Cairo, she worked with refugees. Her very first client, a Liberian teenager, fled his homeland to avoid being forcibly recruited as a child soldier.

She interviewed him several times to put together his appeal. Looking down at the floor, he slouched, mumbling, hand to his mouth, and spoke in a Liberian-inflected English; Mandingo was his native language. Knowing that the United Nations officers interviewing him would be speaking English as a second language too, she advised him to request an interpreter to overcome potential communication barriers.

Six months after her internship, she learned that he’d been accorded legal status as a refugee, and he eventually resettled in the Northeast of the United States. That put him among the less than 1 percent of refugees who are resettled each year in the Global North—countries such as the U.S. and Canada. Most remain in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, often living only a border away from conflict.

“The catalyst for Asylum Access was meeting refugees with tremendous skills and potential who, while they had refugee status, still couldn’t work or go to school,” she said. She also realized that U.N. staff weren’t always equipped, motivated or sufficiently well-resourced to adequately advocate for the human rights of refugees. “Most of the world had no idea that we were condemning people who fled war or targeted violence to years, decades or generations of marginalized existence.”

Yet refugees can be a potent force for development, experts say, contributing to the economies of host countries not only by buying and selling but by creating employment. In Kampala, 40 percent of those employed by refugees are Ugandan nationals, according to a report by the University of Oxford’s Refugees Studies Center.

Arnold-Fernández discusses a family’s case at their home in Bangkok.

In 2005, she and others working in the refugee field started organizing, and by September, she had volunteered to become the executive director of Asylum Access while working as a civil rights attorney part time.

“I like being in charge, and starting things is a good way to get there,” she said with a grin.

She worked on the business plan, and over the holidays, while visiting her parents, she dug up old telephone directories for her high school, choir and cross-country teams and put out an appeal that raised a total of $5,000. (These days, funders include individual donors, grant-making foundations and government donors. Asylum Access raised $2.6 million in fiscal year 2016 and served more than 22,000 refugees in five countries.)

A year later, while traveling to Ecuador, she came down with food poisoning the night before a long day of meetings with government officials and potential donors. Amalia Greenberg Delgado, who was traveling with her, nursed her throughout the night. Neither woman slept well.

Though Arnold-Fernández was ailing and speaking in Spanish, her second language, she made a case for the Asylum Access model of empowerment, pushing the government to allow refugees to bring lawyers to interviews to advocate on their behalf.

“I was impressed by her strength and energy. She bounced back,” marveled Greenberg Delgado, the organization’s director of global programs. “The next morning, she went for a run.”

In the early years, Arnold-Fernández housed Asylum Access in her tiny apartment in San Francisco. In the summer of 2007, she had 10 interns who worked off her couch on TV trays and at the kitchen table—everywhere, she joked, but the bathroom. After she’d spent a week orienting and training them, she handed them keys and flew to Thailand, where she was conducting due diligence to open an office.

“My poor husband had to put up with interns arriving at our doorstep at 9 a.m.,” she said. She’d spend her days in meetings and doing field research, writing up her notes in the evening, and around midnight would respond to emails and chats from her interns, before she went to bed at 4 a.m., getting up three hours later. “A crazy time.”

Her husband, David Arnold-Fernández ’98, whom she met at Pomona, used to stage-manage the Asylum Access summer fundraisers, a skill he’d gained when they were both in a musical theatre group at Georgetown. “She was on stage, and I was behind the scenes,” he said. That same dynamic has reflected how he’s supported her work at Asylum Access, too. “I get out of her way and let her do her thing. She has this attitude that it’s going to work, come hell or high water. She’s always handled it. That’s the thing I’m most proud of her for.”

With that determination, Arnold-Fernández changed the international conversation around refugees. In 2013, Asylum Access won a landmark victory against a restrictive law in Ecuador, which has the largest refugee population in Latin America. The president had decreed that people had to file a petition for legal status within 15 days of arrival—even though many new refugees were in rural areas on the border, far from where they could file. Since the lawsuit, applicants now have three months to file for legal status and 15 days to appeal.

Also around 2013, Asylum Access started building a coalition to advance refugees’ right to safe and lawful employment globally, followed by a groundbreaking report examining those struggles. The deputy high commissioner of the UN’s refugee agency began citing that report, and it also inspired the World Bank to draw up an expanded report, with the assistance of Asylum Access.

Arnold-Fernández pushed for these rights at a time “when no one else was talking about refugees working, and now that’s a part of the common discourse,” said Greenberg Delgado, who has been with Asylum Access since its inception, first as a board member and now as member of the staff.

After more than a decade at the helm of Asylum Access, Arnold-Fernández has been training the next generation of leaders. Last fall, Saengduan Irving joined as Thailand’s country director. Though Irving felt nervous meeting her boss in person, Arnold-Fernández immediately set her at ease with encouraging feedback.

“We talked about what we are going to do to move forward and didn’t worry about the past,” Irving said. “She’s not 50 or 60 years old, like leaders from other organizations. But she’s very mature, very smart. She knows the situation well.”

To remain inspired for decades more, in June Arnold-Fernández began a three-month “CEO Sabbatical” sponsored by O2 Initiatives, designed to revitalize executive directors at nonprofits. It’s the latest in a slew of accolades, including the Dalai Lama’s Unsung Heroes of Compassion Award, the Waldzell Leadership Institute’s Architects of the Future Award, the Grinnell College Young Innovator for Social Justice Prize, and Pomona’s Inspirational Young Alumna Award.

During her sabbatical, she’s devoting herself to playing the violin and singing. In years past, she sang in a local a capella group and performed in the pit orchestra of musicals, but more recently, her travel schedule made it impossible for her to participate.

“I’m not trying to have a product, an output, because I’m so results-focused in my professional life,” she said. “I want to tap into my creativity again, and doing something that’s creative in a different way will make me more creative as a leader.”

—Photos by Thomas De Cian

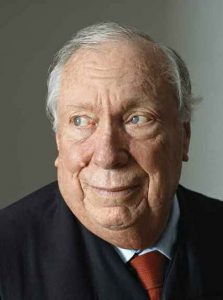

Judge Stephen Reinhardt ’51, a stalwart of the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco who wrote the ruling that ultimately legalized same-sex marriage in California, died March 29, 2018, two days after his 87th birthday.

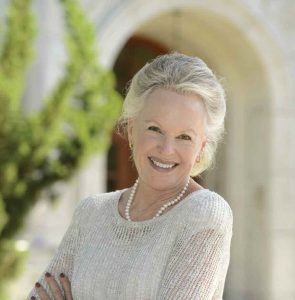

Judge Stephen Reinhardt ’51, a stalwart of the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco who wrote the ruling that ultimately legalized same-sex marriage in California, died March 29, 2018, two days after his 87th birthday. It’s safe to say that no Pomona faculty member has ever been more beloved among students and alumni than Emerita Professor of English Martha Andresen Wilder, who died on March 24 from multiple myeloma at the age of 74. Over the 34 years of her Pomona career, she was honored by the students themselves seven times with the coveted Wig Award for Excellence in Teaching, setting a record in the 60-plus-year history of the award that is unlikely ever to be surpassed. If she hadn’t been ineligible for four years following each win, she probably would have garnered many more.

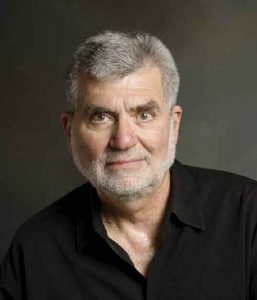

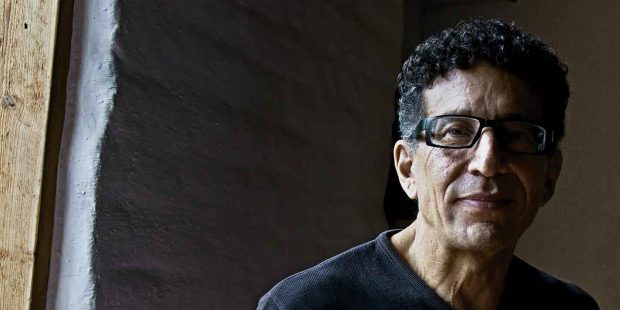

It’s safe to say that no Pomona faculty member has ever been more beloved among students and alumni than Emerita Professor of English Martha Andresen Wilder, who died on March 24 from multiple myeloma at the age of 74. Over the 34 years of her Pomona career, she was honored by the students themselves seven times with the coveted Wig Award for Excellence in Teaching, setting a record in the 60-plus-year history of the award that is unlikely ever to be surpassed. If she hadn’t been ineligible for four years following each win, she probably would have garnered many more. Professor of Theatre Arthur Horowitz, who retired last spring after 14 years on Pomona College’s theatre faculty, passed away suddenly in New Orleans on June 16, at the age of 73.

Professor of Theatre Arthur Horowitz, who retired last spring after 14 years on Pomona College’s theatre faculty, passed away suddenly in New Orleans on June 16, at the age of 73.

During your first semester at Pomona, take a Linear Algebra course with Professor Stephan Garcia, whose problem-solving approach to teaching impresses you so much that you can’t wait to take another course with him second semester.

During your first semester at Pomona, take a Linear Algebra course with Professor Stephan Garcia, whose problem-solving approach to teaching impresses you so much that you can’t wait to take another course with him second semester.

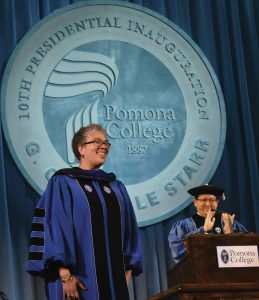

AS HE RETIRES from the Board of Trustees this spring after a tenure of almost 30 years, including nine years as chair, Stewart Smith ’68 has found himself doing a few calculations. Between his father, the late H. Russell Smith ’36, and himself, he estimates that the Smiths have been active members of the College family—as students, engaged alumni and trustees—for roughly two-thirds of the College’s 130-year existence, including more than half a century with at least one Smith on the Board of Trustees and a grand total of 27 years as chair. And that family history remains open-ended since he’s also the father of two Pomona graduates—Graham ’00 and MacKenzie ’09.

AS HE RETIRES from the Board of Trustees this spring after a tenure of almost 30 years, including nine years as chair, Stewart Smith ’68 has found himself doing a few calculations. Between his father, the late H. Russell Smith ’36, and himself, he estimates that the Smiths have been active members of the College family—as students, engaged alumni and trustees—for roughly two-thirds of the College’s 130-year existence, including more than half a century with at least one Smith on the Board of Trustees and a grand total of 27 years as chair. And that family history remains open-ended since he’s also the father of two Pomona graduates—Graham ’00 and MacKenzie ’09.