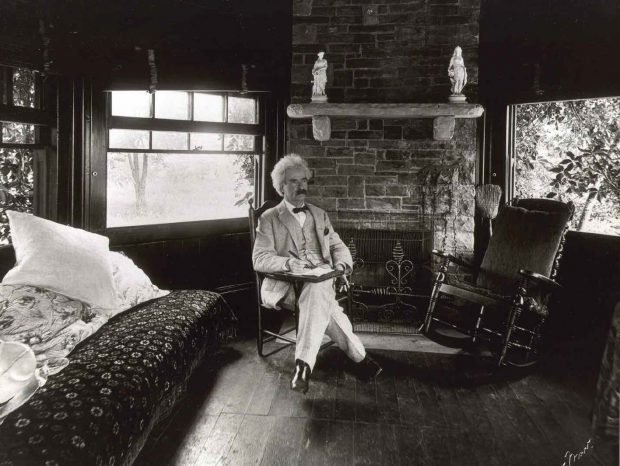

Mark Twain at Quarry Farm

I HAVE A PICTURE of myself as a child, sitting on the very porch where, 30 years later, I am writing these words. Quarry Farm hasn’t changed much since my last visit, although most of my life has.

As a kid, I spent a couple of summers at Mark Twain’s Quarry Farm—the house in Elmira, New York, where Twain lived and wrote books like Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Life on the Mississippi, and Tom Sawyer—because my father, Wilson Carey McWilliams, was a great teacher of Twain’s work and a scholar-in-residence here. During the days, my sister and I romped around the grounds while Dad held seminars.

At night, just as Twain had done for his own daughters, Dad made up stories for us based on the pictures on the fireplace tiles in the parlor. And he read us Twain, of course: the stories and the novels and the bull’s-eye critique of James Fenimore Cooper that always made me laugh, even though I’d never read anything by James Fenimore Cooper.

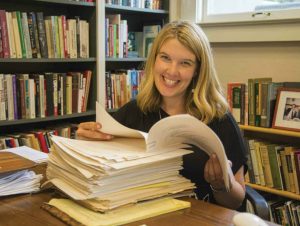

Susan McWilliams in her office with her father’s manuscript and files

My father dropped dead 12 years ago, on a sunny Tuesday morning, leaving behind notes on the manuscript about Mark Twain that he’d been working on for decades. His friends and colleagues mourned the lost book, but of course the manuscript was not the main thing. The more pressing concern was just getting through the day; Dad, a big-hearted, big-hugging, big-thinking man, left an absence that felt even bigger than his presence. Grief had me by the throat.

I got my dream job, teaching at Pomona College, a few months later.

I tell my students, sometimes, that grown-ups are not lying to you when they talk about how fast life goes. You wake up and really do wonder where it all went—which is why one of the great luxuries afforded Pomona students is the freedom to sit down on Marston Quad or in a dorm room and to talk with friends, or to think for yourself, about where you want to be and, more importantly, with whom you want to be there. Your job isn’t just to learn a subject. It’s to learn to live a good life.

And so it is years later, and I have my own children now, and they are almost the age that I was when we spent that first summer at Quarry Farm. And they love stories that are the stuff of Twain: kids getting in trouble, kids being sneaky, kids in danger, knights, tricks, grownups who do stupid things, those rare acts of true bravery and courage that make you believe human beings might be worth something, after all.

Perhaps all that storytelling has something to do with why I finally picked up those old manuscript notes—and why this summer, I’m the professor working at Mark Twain’s house, as a fellow of the Elmira College Center for Mark Twain Studies, trying to finish a book that my father was writing before I was born.

One of Twain’s great themes was that the American myth of individual autonomy and self-creation is a lie—a lie that enabled the great moral evil of slavery, for one thing, but that also impoverishes our lives in subtler ways. Huck Finn has a lot of adventures, but other Americans are always trying to get one over on him, and Huck feels “awful lonesome” most of the time.

The truth about us humans, Twain taught, was that we are social and political creatures who are inextricably bound to other people. Love calls us and can ennoble us, and Twain was “confident,” my father wrote, “that the comradeship of honorable love is the clearest human instance of what is divinely right.”

Twain knew that we have to admit our connection and indebtedness to others if we are ever to know ourselves. And we have to be willing to dedicate ourselves to others, and to do so out of love, if we are ever to be truly free, to smile in the face of our certain deaths.

My father wrote this: “Love, particularly when it is linked to the rearing of children, can nurture and sustain the spirit, even in a gilded age, just as a great storyteller can help us to hear the music in our souls.”

And so it is that here I am, on this front porch looking out at the hills of upstate New York, at home again with my father, and at home again with Mark Twain, with the abiding refrain in my ears.

Susan McWilliams is associate professor of politics and chair of the Politics Program at Pomona College. The author of Traveling Back: Toward a Global Political Theory, she has two books in the publishing pipeline ahead of the Twain book.