For Carole Regan ’58 and Valkor, guide dog training was the beginning of a wonderful friendship.

When I became legally blind several years ago, I first asked the Braille Institute for a white cane. Although the institute gave me excellent mobility training, the cane only helps detect obstacles when you encounter them. As my vision worsened (now 20/350), I felt the need to avoid obstacles, and that’s the job of a guide dog.

Applying to guide dog school reminds me of applying to Pomona many years ago: neither is for the casually interested and all requirements must be met. Once you’ve decided which school to attend (there are three in California, all funded through charitable donations), you’ll need to line up references, including your physician (are you healthy enough to complete the strenuous training?), your opthalmologist/optometrist (how bad is your vision loss?) and your mobility instructor (can you travel independently using a cane?). Last, you may be asked either to schedule a home visit or to submit a video of your walking and immediate environment.

The first school to which I applied sent a trainer to interview me, but after a walk, he announced that the school would be unable to match me with a dog because I walked “too slowly.” I was stunned, then disappointed, then angry, as his reason smelled of blatant age discrimination.

After submitting another lengthy application to a different school, however, I was thrilled to receive a phone call from Guide Dogs of America (GDA) in Sylmar, accepting me for its November–December 2017 class.

And so, the Sunday after Thanksgiving, there I was sitting with a six-month-old Labrador puppy named June at my feet as Charlene, one of hundreds of volunteers at Guide Dogs of America and a puppy raiser, threaded her way through traffic in downtown L.A. As my apprehension grew, I peppered Charlene with questions about June, but silently, other questions arose that I dared not voice: At 81, how would I manage in a class of much younger students? Would I disgrace myself and future older applicants by “washing out”? These and other doubts would haunt me for the remainder of my stay at GDA.

When we reached GDA’s dormitory, a pleasant young woman named Kim led me into a large entry hall dominated by a very long, corner sofa, explaining that this would be our meeting area. Then she walked me down the long hallway to my room.

At 4 o’clock, our group assembled on the sofas. Five men and four women introduced themselves and shared their causes of blindness, the only characteristic we appeared to have in common. The causes varied from childhood cancer to a severe fall to my macular degeneration. Six of us were getting our first guide dogs and three were back for a refresher course.

The instructors’ were as varied as their students: Two of the credentialed instructors, including Kim, had been trained at Eastern guide dog schools. The third, plus the apprentice instructor (in her first year of a three-year program), had started as volunteers. The head instructor had aspired to be a marine animal trainer at Sea World, but failing that, she had turned instead to training tigers at the Bronx Zoo before gravitating to the safer population of guide dogs.

We learned the rules: no in-room visiting, no alcohol on site, silenced cell phones, promptness for all meetings and meals, walking on the right side of hallways and respect for the rights of others. We would meet at 8 each morning and train until nearly lunchtime. After lunch, we would train again until 4. Only after feeding, watering and relieving our dogs would we have dinner, and after dinner we would often meet again. w

There was no free time, except for a few hours on Saturday afternoon and Sunday. A climate of anxiety filled the air. I think we all feared being sent home in disgrace without a dog.

In the evening, the hazards of living in a blind community became apparent: several of the students became confused about the location of their rooms and nearly collided. Collisions, in one form or another, would be a constant concern for the entire three weeks.

I slept very little that night. After breakfast the next morning, we gathered on the sofa for a lecture, then set off for a “Juno” walk, with the instructors playing the part of guide dogs. We were, it seemed, being evaluated for walking pace.

Excitement grew on Wednesday—the day we would be given our dogs. The instructors enjoyed our excitement, offering to give the first dog to the student who guessed her dog’s name. No one managed—certainly not I. (Who could have imagined “Valkor?”)

Wednesday came, and after lunch we were instructed to return to our rooms and be ready to meet our dogs. There was a knock at the door, and Kim and Valkor appeared with his trainer. Valkor, named by his puppy raisers for a character in a children’s cartoon, is an 85-pound black Labrador-retriever cross and quite handsome. He immediately headed for a toy I had brought with me. I felt somewhat intimidated by his size—it would take me some time to appreciate better his intelligence and calm disposition. Valkor then wanted to show me that he could sit on his haunches and hold up his front paws.

Exactly how we were matched with our dogs remains a mystery, but it seemed to be primarily a matter of walking pace and energy level. Our youngest student received a high-energy dog, and Valkor was described as “a gentle giant.” In any case, the matching seemed to work. We gathered for dinner with nine tails under the table. Everyone seemed very happy.

When packing for my three weeks at GDA I had thrown in a lightweight rain jacket, but instead of rain, that first weekend brought severe dry winds, the dreaded Santa Anas. Monday brought an acrid odor to go along with the strong winds. As we trained that morning, the winds became so strong that at times I had trouble remaining upright. Our eyes burned. All signs warned of fire, but we continued training.

Tuesday morning the odor worsened, and I was glad I had also packed several masks. After our usual morning lecture, we were sent to our rooms to relieve our dogs and wait for an announcement. We all assembled on the sofa to hear the GDA president tell us that those who lived in the area should make plans to return home; those farther away would be sent elsewhere. We were to take our dogs.

Three left; six were accommodated in the homes of staff members and volunteers. Instructions were to pack for an evacuation of several days. Fires had broken out in multiple locations, including Sylmar.

I stuffed a makeshift duffle bag with essentials, including several gallon bags of dog food. Valkor and I met Sue, the GDA bookkeeper, who drove us to her home in East L.A. on the border of Pasadena. Freeway closures forced her to drive alternate routes.

Sue and her husband live in a Craftsman bungalow with two dogs and a grown daughter. Another daughter drops her dog off for day care, so that small house now sheltered four dogs. Luckily, their home also included a small yard accessible via a doggie door. Valkor needed no instructions on its use.

Valkor and I occupied an empty room used for storage. At periodic intervals, Sue’s son—also an employee of GDA— called home to report that the fires were still distant. Fortunately, they would remain so. Valkor amazed me by deferring to the two resident dogs and seemed to understand he was a guest. We were getting to know each other and quickly became fast friends.

Thursday afternoon, Valkor and I piled into Sue’s car for the return trip, stopping to retrieve one of my classmates and her dog on the way. That evening the returning students seemed sober as we recounted our experiences. We all speculated on whether graduation would be postponed. But instead, we were to expand our days and week to make up lessons missed. We would walk several miles in the mornings, afternoons and some evenings, including Saturday.

But what we had missed in techniques we had gained in the vital process of bonding with our dogs, difficult under tight schedules.

In our remaining time, we focused on essentials and tried to ignore the unhealthy air quality and ashes covering the ground. Happily our lessons were mostly out of the area as we learned to negotiate malls, suburban neighborhoods lacking sidewalks, the Pasadena light rail, a city bus, and comfortable parks surrounding lakes. We practiced fending off persistent strangers insisting on petting our dogs. We learned about “intelligent disobedience,” leading guide dogs to disobey the command of “forward” if the situation is unsafe. Valkor, who looks both ways before crossing a street, will not proceed if a car is approaching.

As we entered the third week, our lectures became more intense, covering such complicated topics as negotiating the TSA and airline personnel. We were all exhausted from the stress and began to drowse on the sofas. My blistered, swollen feet hurt from constant walking.

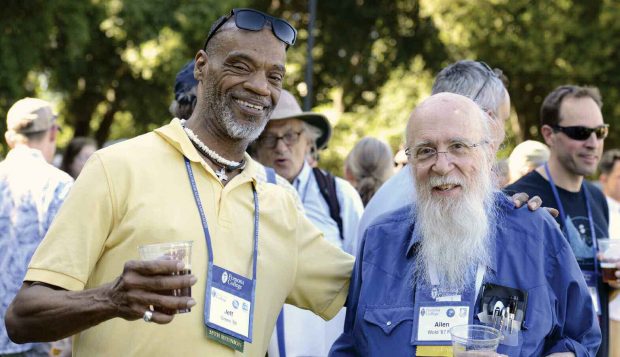

When graduation came, we sat with our dogs in the front row of the large auditorium packed with families, friends and hundreds of volunteers with their dogs, and then took our turns at the podium. When it was my turn, after thanking Valkor’s puppy raisers and the instructors, I cited Joseph Jones, the welder who was rejected by several schools back in 1948, at age 57, because he was “too old” to profit from a guide dog. His machinists’ union then hired a trainer and found a suitable dog. Next, the union established what became Guide Dogs of America, with Jones as its first graduate.

I said that “many organizations espouse nondiscrimination, but GDA practices it.” Then I broke down in tears: At 81 I had survived strenuous training and would certainly profit from having Valkor as my guide.

Now it was time to celebrate.

This spring, the Pomona College Book Club will discuss The Lost City of the Monkey God: A True Story by Douglas Preston ’78. Named a New York Times Notable Book of 2017, the story follows Preston’s rugged expedition in search of pre-Columbian ruins in the Honduran rain forest. Join the

This spring, the Pomona College Book Club will discuss The Lost City of the Monkey God: A True Story by Douglas Preston ’78. Named a New York Times Notable Book of 2017, the story follows Preston’s rugged expedition in search of pre-Columbian ruins in the Honduran rain forest. Join the

Alumni Weekend 2018

Alumni Weekend 2018 Pomona in the City: Seattle

Pomona in the City: Seattle

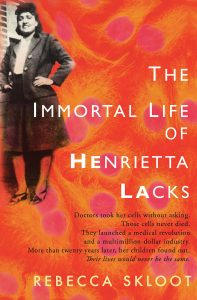

GRAB A BLANKET (or, if you’re in Claremont, maybe a fan) and cozy up with The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, the Pomona College Book Club selection for fall. This New York Times bestseller was adapted earlier in the year into an Emmy-nominated HBO television film, directed by Tony Award–winning playwright and director George C. Wolfe ’76. In a September 2017 interview for the website

GRAB A BLANKET (or, if you’re in Claremont, maybe a fan) and cozy up with The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, the Pomona College Book Club selection for fall. This New York Times bestseller was adapted earlier in the year into an Emmy-nominated HBO television film, directed by Tony Award–winning playwright and director George C. Wolfe ’76. In a September 2017 interview for the website  DO YOU REMEMBER feeling unsure about your path after Pomona? Are you interested in ways that you can give back to the student community? Sagepost 47 is Pomona’s alumni-student mentorship program, founded by a team of students and alumni in 2014. The program connects alumni mentors with students, provides support for career and graduate school exploration and allows students to participate in mock interviews in a variety of fields. Visit

DO YOU REMEMBER feeling unsure about your path after Pomona? Are you interested in ways that you can give back to the student community? Sagepost 47 is Pomona’s alumni-student mentorship program, founded by a team of students and alumni in 2014. The program connects alumni mentors with students, provides support for career and graduate school exploration and allows students to participate in mock interviews in a variety of fields. Visit  LORN FOSTER, Pomona’s Charles and Henrietta Johnson Detoy Professor of American Government and Professor of Politics, has announced his retirement at the end of this academic year—his 40th at the College. A special fund supporting student internships and Pomona’s golf program has been established in his honor. Foster fans who wish to honor his legacy with a gift should visit pomona.edu/give and select the “Lorn S. and Gloria F. Foster Fund” from the gift designation menu. To hear about events celebrating Professor Foster, make sure

LORN FOSTER, Pomona’s Charles and Henrietta Johnson Detoy Professor of American Government and Professor of Politics, has announced his retirement at the end of this academic year—his 40th at the College. A special fund supporting student internships and Pomona’s golf program has been established in his honor. Foster fans who wish to honor his legacy with a gift should visit pomona.edu/give and select the “Lorn S. and Gloria F. Foster Fund” from the gift designation menu. To hear about events celebrating Professor Foster, make sure

Thank You, Jordan!

Thank You, Jordan! Introducing Regional Book Club Discussions

Introducing Regional Book Club Discussions

The Handmaid’s Tale

The Handmaid’s Tale

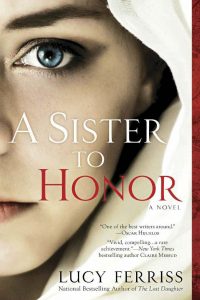

Lucy Ferriss ’75 is the author of 10 books, most recently A Sister to Honor, a novel about Afia Satar, the daughter of a landholding family in northern Pakistan who attends an American college. Over and against Pashtun tradition and family dictates, Afia loves an American boy. Photos of the two of them together surface online, and her brother, entrusted by the family to be her guardian, is commanded to scrub the stain she left. In the book, Ferriss explores two contrasting worlds and entangled questions of love, power, tradition, family, honor and betrayal.

Lucy Ferriss ’75 is the author of 10 books, most recently A Sister to Honor, a novel about Afia Satar, the daughter of a landholding family in northern Pakistan who attends an American college. Over and against Pashtun tradition and family dictates, Afia loves an American boy. Photos of the two of them together surface online, and her brother, entrusted by the family to be her guardian, is commanded to scrub the stain she left. In the book, Ferriss explores two contrasting worlds and entangled questions of love, power, tradition, family, honor and betrayal.