Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsessions

Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsessions

Rachel Monroe ’06, hailed as one of the “queens of nonfiction,” by New York Magazine, pens the stories of four women’s obsession with true crime and explores our collective morbid fascination.

Frost Fair Dance

Frost Fair Dance

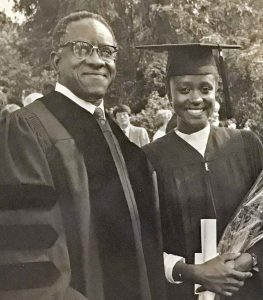

Dancer and poet Celestine Woo ’89 offers a book of poems that, as one editor praised, “glide across the page” —an apt description as Woo uses modern dance and movement as themes throughout her work.

Best Practices in Educational Therapy

Best Practices in Educational Therapy

Ann Parkinson Kaganoff ’58, a board-certified educational therapist and educator for six decades, offers strategies and solutions for novice and veteran educational therapists alike.

Doing Supportive Psychotherapy

Doing Supportive Psychotherapy

John Battaglia ’80, professor of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin, has written a guide for learners and professionals alike on how to forge meaningful, impactful therapeutic relationships with patients.

One Small Sun

One Small Sun

The poetry of Paulann Petersen ’64 takes readers from Oregon to India, taps into memory and tells the tales of an aging woman’s life.

The Road Through San Judas

The Road Through San Judas

The inspiration for this novel by Robert Fraga ’61 came from his time as a volunteer in Northern Mexico, where he learned of the conflict between landless Mexican farmers and a wealthy Juárez family who wanted their land.

Can’t Stop Falling: A Caregiver’s Love Story

Can’t Stop Falling: A Caregiver’s Love Story

In a memoir written to inspire people helping loved ones who are suffering, W C Stephenson ’61 tells the story of his wife’s rare neurological disease and his role as her caregiver.

Forty Years a Forester

Forty Years a Forester

Professor of Environmental Analysis Char Miller edited an annotated edition of the memoir of Elers Koch, a key figure in the early days of the U.S. Forest Service with a major role in building relationships and policies that made the bureau the most respected in the federal government.

Try not to drool when you read the menu that won Pomona College chefs Amanda Castillo, John Hames, Marvin Love and Angel Villa a silver medal in a recent national cooking competition.

Try not to drool when you read the menu that won Pomona College chefs Amanda Castillo, John Hames, Marvin Love and Angel Villa a silver medal in a recent national cooking competition.

Professor of Physics and Astronomy David Tanenbaum keeps this broken pink bowling ball in his office as a reminder of a project that he considers to be one of the most important responsibilities of his career—playing the lead role in providing faculty oversight for the design, planning and construction of the new Millikan Laboratory for Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy. The last step in that long and arduous process was the grand opening of the new facility on Founders’ Day 2015. In planning for that special event, the question arose: How should they christen the new building? The answer to that question involved some showmanship, some real physics and, incidentally, the destruction of a bowling ball.

Professor of Physics and Astronomy David Tanenbaum keeps this broken pink bowling ball in his office as a reminder of a project that he considers to be one of the most important responsibilities of his career—playing the lead role in providing faculty oversight for the design, planning and construction of the new Millikan Laboratory for Physics, Mathematics and Astronomy. The last step in that long and arduous process was the grand opening of the new facility on Founders’ Day 2015. In planning for that special event, the question arose: How should they christen the new building? The answer to that question involved some showmanship, some real physics and, incidentally, the destruction of a bowling ball.