GATHERED ON THE pitcher’s mound during class, Pomona College students feed balls into a pitching machine, then quickly glance down at an iPad.

GATHERED ON THE pitcher’s mound during class, Pomona College students feed balls into a pitching machine, then quickly glance down at an iPad.

On the ground between them and home plate is a boxlike device called a Rapsodo, a $4,000 radar-based system that provides data not only on pitch velocity, but also spin rate, spin axis, horizontal and vertical break, 3D trajectory and a strike zone analysis.

The Rapsodo device provides pitching data that includes velocity, spin rate and vertical and horizontal break.

Welcome to PE 086: Baseball Analytics, a new course taught by Frank Pericolosi, a professor of physical education and coach of the Pomona-Pitzer baseball team.

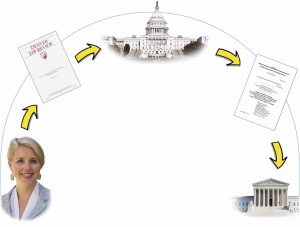

The class formalizes what has emerged as a notable career path for Pomona alumni: More than a dozen graduates or current students have put backgrounds in mathematics and computer science to work for Major League Baseball teams analyzing the game-changing explosion of data in baseball.

They’re following a trail blazed by Guy Stevens ’13, a former Sagehens pitcher and math major who has risen to senior director of research and development/strategy for the Kansas City Royals. He was on staff for a World Series championship in 2015, less than three years after working with Math Professor Gabe Chandler to publish a statistical analysis of minor league data.

“Talking to Guy [Stevens] over the years, I ask, ‘What do we need to be doing on campus to make these kids better candidates for these internships and for these jobs?’” Pericolosi says. “He gave some suggestions in terms of, ‘They need to be doing creative, innovative projects on their own.’ The driving force for getting this technology on campus was initially to help our kids who want to go into analytics. Also, we’re in a heavy-data era of baseball even more so than before, and it’s going to give us good data to evaluate our players as well.”

Five of the 15 students in the class play baseball for the Sagehens. One of them, catcher and math major Jack Hanley ’20, worked for the Oakland Athletics two summers ago and spent last summer as an associate in quantitative analysis with the New York Yankees. This October, he watched his former colleagues advance to the American League Championship Series.

“It’s definitely very rewarding to know that whatever small role I played this summer in making the team better, it paid dividends,” says Hanley, whose description of his research for the Yankees is vague. That’s because he had to sign a non-disclosure agreement to protect what amount to industry secrets.

Not all the alumni putting data analysis to work for major league teams are former baseball players. Jake Coleman ’13 played Ultimate Frisbee at Pomona but completed a Ph.D. in statistics at Duke University in May and joined the Los Angeles Dodgers in August as a senior quantitative analyst. Nor are they all men: Christina Williamson ’17, a former water polo player and swimmer who majored in math, was featured by The Athletic as one of 35 people under 35 shaping the game of baseball for her work with the Yankees using biomechanical data to aid player development and reduce injuries.

Pomona, Stevens is confident, is gaining a reputation in the game.

“If you think about how small the sport is, with only 30 teams, and how well-connected it is, there’s a pretty good chance if you’re in baseball, you know someone who knows someone who went to Pomona,” he says. “A lot of these jobs in baseball, it’s the same set of skills that translate anywhere: If you’re working with data, it’s curiosity and creativity and thinking outside the box. And Pomona trains you for that 100%, whether it’s baseball or finance or whatever else.”

Baseball analytics once was based on information available in a box score, but has evolved rapidly in the era since it was popularized by the 2003 book Moneyball and the movie that followed. It is now decidedly high-tech, requiring expensive equipment that Pericolosi was able to purchase for the course through Pomona’s Hahn Teaching with Technology Grants. He’s in the process of acquiring a second Rapsodo that gathers hitting data, measuring such things such as exit velocity—the speed of the ball off the bat—launch angle, 3D ball flight and expected landing location. Blast Motion swing sensors that attach to the knob of a bat are yet another tool in an array of devices that are used in training to aid the development of players and to help shape strategies.

Though some of the students in the class chose the course as an intriguing elective—Noah Sasaki ’20 thinks it could help him in a planned sports media career—those who play baseball are earnestly using the data to improve their skills and approaches. Analyzing spin data has helped catcher Jake Lialios ’20 and pitchers Luka Green ’20 and Simon Heck ’22 determine a particular pitcher on the staff should throw higher in the strike zone because the spin rate makes his fastball appear higher than it is. Green suggests data also could be used to recognize injuries.

“If your slider spin rate gets cut in half, your elbow probably hurts—and sometimes people don’t tell anyone,” he says.

Hanley plans to use bat sensor data to study swing paths in a senior thesis supervised by Chandler, the math professor and former assistant baseball coach whose mentorship helped launch Stevens’ career. After Stevens showed Chandler a trove of minor league data he was struggling to shape into a project, the pair joined forces and published an article in the Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports in 2012. That, plus an introduction from Chandler to an East Coast statistics professor who also worked with the New York Mets, helped Stevens break into Major League Baseball.

“At that point, people at Pomona realized this is something that one can do,” Chandler says. “I don’t know if people were thinking this before they decided to enroll here, but all of a sudden we went from having almost no math major baseball players to having two or three a year.”

Hanley, who communicated with Stevens even before arriving at Pomona, would love to follow the same sort of path. For his thesis, he is building on research he began with the A’s to study swing mechanics through functional data analysis, a statistical method Chandler calls “cutting-edge stuff.”

“What I’m really interested in is the function of position or acceleration over time—not just to reduce the entire function down to one point, but to use the entire function in data analysis,” Hanley says. “Generally, the project is to look at these swings and see how much information we can really glean. Let’s not limit ourselves in terms of format or data structure. Let’s see what we can really do with this stuff.”

After graduation, Hanley hopes to land a position with a baseball team, but he notes that more and more baseball analytics researchers have graduate school training and he might also go that route after a couple of years. Peter Xenopoulos ’18, who has worked for the Philadelphia Phillies as a quantitative analyst associate, is now a Ph.D. student in computer science at NYU, and Mike Dairyko ’13 earned a Ph.D. in applied math at Iowa State and works as a data scientist for the Milwaukee Brewers, though he is on the business side. “I do think this is something where Pomona is getting a reputation,” Hanley says. “It’s really a great breeding ground, a great incubator for baseball analytics in college.”

Pomona’s Baseball Analysts

The following is a list of recent Pomona alumni who have worked for MLB teams in roles related to data and analytics:

Drew Hedman ’09

Run Production Coordinator

Arizona Diamondbacks

Guy Stevens ’13

Senior Director, Research & Development/Strategy

Kansas City Royals

Jake Coleman ’13

Senior Quantitative Analyst

Los Angeles Dodgers

Mike Dairyko ’13

Senior Manager, Data Science, Business Analytics

Milwaukee Brewers

Jake Bruml ’15

Pro Scouting Intern

Boston Red Sox

Kevin Brice ’16

Quantitative Analysis Assistant

Los Angeles Angels

Simon Rosenbaum ’16

Assistant, Baseball Development

Tampa Bay Rays

Dylan Quantz ’16

Player Development Assistant

Atlanta Braves

Christina Williamson ’17

Research Analyst, Performance Science

New York Yankees

Peter Xenopolous ’18

Former Quantitative Analyst Associate

Philadelphia Phillies

Bryce Rogan ’18

Quantitative Analysis Assistant

Los Angeles Angels

Andrew Brown ’19

Apprentice, Baseball Analytics

Texas Rangers

Jack Hanley ’20

Former Summer Associate

New York Yankees

Nolan McCafferty ’20

Former Quantitative Analyst Intern

Baltimore Orioles

Sometime this fall, the Pomona College Museum of Art will cease to exist, and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College will be born in its beautiful new quarters on the opposite corner of the intersection of College and Second. To prepare for that change, for the past few months, the museum’s associate director and registrar, Steve Comba, has been overseeing the effort to inventory, pack and safely move approximately 15,000 valuable and often fragile art objects from the museum’s old storage into the new. Already in their new home are the artifacts of the museum’s Native American collection, previously stored in the basement of Bridges Auditorium and brought out mainly for visiting schoolchildren.

Sometime this fall, the Pomona College Museum of Art will cease to exist, and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College will be born in its beautiful new quarters on the opposite corner of the intersection of College and Second. To prepare for that change, for the past few months, the museum’s associate director and registrar, Steve Comba, has been overseeing the effort to inventory, pack and safely move approximately 15,000 valuable and often fragile art objects from the museum’s old storage into the new. Already in their new home are the artifacts of the museum’s Native American collection, previously stored in the basement of Bridges Auditorium and brought out mainly for visiting schoolchildren. It’s time to mark your calendars for a return to campus on Alumni Weekend 2020, which will take place April 30 to May 3. For more information, go to the

It’s time to mark your calendars for a return to campus on Alumni Weekend 2020, which will take place April 30 to May 3. For more information, go to the

CASH. BABY. BOOM. Stocks with clever ticker symbols such as these continue to outperform the market as a whole, a new study has confirmed.

CASH. BABY. BOOM. Stocks with clever ticker symbols such as these continue to outperform the market as a whole, a new study has confirmed. GATHERED ON THE pitcher’s mound during class, Pomona College students feed balls into a pitching machine, then quickly glance down at an iPad.

GATHERED ON THE pitcher’s mound during class, Pomona College students feed balls into a pitching machine, then quickly glance down at an iPad.

THE POMONA-PITZER men’s cross country team claimed its first national championship last fall, winning the NCAA Division III title in Louisville, Kentucky.

THE POMONA-PITZER men’s cross country team claimed its first national championship last fall, winning the NCAA Division III title in Louisville, Kentucky. WIN NO. 500 ARRIVED in January for Coach Kat—or, more formally, Professor of Physical Education and Men’s Basketball Coach Charles C. Katsiaficas.

WIN NO. 500 ARRIVED in January for Coach Kat—or, more formally, Professor of Physical Education and Men’s Basketball Coach Charles C. Katsiaficas. EVERY SENIOR ON the Pomona-Pitzer women’s soccer team that has reached the Final Four of the NCAA Division III Championship for the first time knows exactly how slender the margin between winning and losing could be

EVERY SENIOR ON the Pomona-Pitzer women’s soccer team that has reached the Final Four of the NCAA Division III Championship for the first time knows exactly how slender the margin between winning and losing could be