Photos by Sean McCoy ’16

RAY FLICKED HIS razor and bent over the lifeless heifer and cut a long backwards L across her torso. He sank his fingers into the seam and peeled away the hide, scoring and pulling until we could see the white outlines of rib. He stood and scanned the arroyo: tumbleweed, pigweed, bare earth, the remains of a nearby bone pile. He chose a weathered femur and brought it down on her ribs, hard, four times, stopping when we heard a crack. I shoved my boot behind her shoulder and pushed it forward to give him room to work. He severed the connecting ligaments, slipped and released a spew of guts, readjusted, yanked free the rib. I watched him place it carefully beside the femur, both bones propped perpendicular against the animal’s jaw. More cuts, more blood, and a large slab of lung appeared in his hands, dark and splotched, scattered with pustules, smelling of rotten hamburger. He squeezed it gently. Hear the crinkle? It’s not supposed to sound like that.

The heifer had been alive that morning. She lay with her head in the grass as we approached, forelegs splayed out, choking on the cool air. We returned 30 minutes later with syringes of Banamine, Baytril and penicillin but never got the chance to use them. At the end of the day, after doctoring 50 more calves, snotty and hacking from the recent cold snap, we took the four-wheeler down to the ranch graveyard to perform an autopsy. I rode home with her left lung in a plastic grocery bag.

***

A YEAR AGO, I never expected to be herding cattle in the deserts of the Southwest. I believed, as I had told Josie, walking the streets of Silver Lake one evening before I left, that movement was a strange way to understand settlement; that running off to work on a ranch would yield more of the road than the hearth; that departure was the wrong way to escape departure, but that it might also be the only way, or at least, the way for me.

A YEAR AGO, I never expected to be herding cattle in the deserts of the Southwest. I believed, as I had told Josie, walking the streets of Silver Lake one evening before I left, that movement was a strange way to understand settlement; that running off to work on a ranch would yield more of the road than the hearth; that departure was the wrong way to escape departure, but that it might also be the only way, or at least, the way for me.

We walked another circle around her block. Josie knew I had bounced around growing up. She knew what it was like because she had been through it too. I admitted apathy for the cycles of goodbye and hello, the expanding and fraying of social circles, the learning and forgetting of street names. She shared my feelings, but she didn’t believe movement had rendered us homeless. She told me she felt at home wherever, whenever she was with her family, and that location was merely a means to that end.

Home requires time, I argued. It often has more do to with one’s place in the past than one’s place in the present. I don’t have enough history to be at home here, I told her. I also tried to tell her that she wasn’t at home either, as if we were having an empirical disagreement about the location of the restaurant we just came from, and as if that dispute could be resolved by retracing our steps: a left turn, down the hill, over the bridge, another left turn.

She pressed me on the unavoidable connections that even a short stay in a new place can generate; how people, impressions, experiences pull us into unfamiliar orbits that soon become our own. She said I hadn’t considered the depth of history within families. Those relationships exert more gravity than longitude and latitude.

We said goodbye and I drove away, wending between the glass and concrete hoodoos of downtown, the slush of automobiles, billboards of automobiles, billboards of movies, of movie stars. I wondered if it would be easier to navigate Los Angeles through a screen, and if people who have never lived here might, in some crucial way, know the city better than I do. I passed another billboard. We Buy Ugly Houses. At least they have seen what produced this place, what this place produced.

***

SO I DEPARTED, traveling east, or West, into something I believed was my past. I stopped in Long Beach, where I was born, to say goodbye to my grandparents. I zipped through Phoenix, where I was raised, without veering from the interstate. I called my parents in New Jersey and explained that cell service would be spotty, and that they’d hear from me, sometimes. I drove until I arrived in the mountains of the Mescalero Apache reservation, surrounded by pinyon and juniper, branding irons and barbed wire, the thrill of a blank beginning.

The work refreshed me and exhausted me, provided a welcome change from sedentary life as an editor in Los Angeles. I was outside and using my body, joined by a team of dogs and horses, caring for cattle, mending fence, keeping up with the waters. I lived in a small trailer an hour from town by dirt roads; the distance grounded me, seemed to override the experience of sleeping each night in a bed anchored by wheels.

I befriended an elderly Apache man—Bloody, he insisted I call him—who approached me near the entrance to a tipi at the Fourth of July feast. I soon learned that he, in his youth, had trained horses and herded cattle in the pastures I’d come from that morning. We stood and ate from paper plates, watching the descendants of Geronimo stomp to the same drumbeats that ushered their ancestor to war more than a century ago.

Bloody’s nose was crooked, his teeth both there and not, his left eye missing a fleck of pupil. He lost the teeth because he started dipping at 17, he explained, but he was in better health than a lot of his friends; they had drunk too much trough water. He winked and told me to stay away from that stuff. Just stick to bourbon and Coke. I laughed. I said I just came from the rodeo; did you see it too? Ah, no, he had to miss it. He had been taking his daughter to the dentist, but how was it? Did any of the bull riders last eight seconds? Yes, there were a few, I said.

We continued to watch the ceremony. A new song began in honor of a member of the tribe—healer, father, friend —who had recently passed away. Bloody turned to me and put his hand on my shoulder. You’re part of this now, he said. Being here, this is for you too. These dances, these songs, they are for everybody, all the Earth.

***

THE NEXT DAY, on a different ranch west of Tucumcari, New Mexico, I loaded the four-wheeler with buckets of toxic pellets and drove out to kill trees. Juniper, mainly, as well as mesquite. Our dog Sophie joined me, riding shotgun to the top of the mesa, where we parked our supplies and set to work. I pulled on gloves and grabbed the first bucket. I walked to the far corner of the pasture and dropped five pellets at the base of the nearest tree. I walked three more feet to another tree and did the same. My gloves turned white.

Tree by tree, pellet by pellet, beginning to perspire beneath an early August sun, I paced an imaginary grid. Certain trees I left alone, the largest ones, to provide shade for cattle on days like today. Sophie trotted and wagged alongside me. I was pleased too. Pleased to walk where I hadn’t walked before, to be outdoors on a clear day with a sky that stretched from the Mesa Rica to the Canadian Escarpment, and pleased to be greeting every single tree.

I had never walked like that. I had walked between trees, through trees, among trees, but never to trees. I began to know them personally—their bark, branches, shape of overhang. I knew their knots and facial features, the emotion in each contortion. And with this knowledge, I bowed to them, depositing pellets at their feet. I remained estranged from those whose lives I spared. But my trees would not die yet; first they needed rain, a good storm to soak the earth and dissolve the pellets, allow poison to seep into soil and root.

I continued to walk and scatter pellets. I occasionally looked over my shoulder to ensure Sophie didn’t taste any. Then, after another few hours, my pleasure dissipated. The work became boring, monotonous, and so, with more buckets and trees left to go, I searched for escape. I began flinging pellets. I sang tuneless, made-up songs in blank verse. I skipped and spun, engaging the torque of my body, hurling handfuls farther and wider and hoping blithely they fell within soaking range. My grid disappeared. I emptied the bucket, retrieved a new bucket, started again at the other side of the pasture. I stopped, at last, when I began scattering atop earlier pellets.

Killing trees grows grass, my boss had explained. He said a variety of factors—fire prevention, overgrazing, a change in climate—had allowed saplings to spread without restraint, yielding denser, more resilient stands that suck precious water from the soil. Juniper, like eucalyptus, is an allelopathic species; the tree excretes chemicals which impede the growth of other plants—especially grasses. He showed me pictures of a savanna-like landscape. This was near here, he said, before we knew better.

He framed the killing as restorative: I was returning the land to its previous condition. I was also improving water retention in our soil, sequestering greater amounts of carbon, strengthening the habitat for rodents and insects, and diminishing the likelihood that a future fire would grow to outsized proportions. More grass means fatter cattle, my boss admitted, but fatter cattle can also mean a healthier ecosystem.

Sophie and I took the long way home. We dropped off the backside of the mesa into a valley where Spaniards and their descendants have been grazing livestock for centuries. We passed the rock-house ruins of early Texas homesteaders, bones of their deceased pear trees, a crested boulder with graffiti scratched alongside petroglyphs. I steered us to the old cemetery, where we read the tombstones with names belonging to our neighbors. Sophie jumped out in chase of wild turkey. I returned to my little blue single-wide.

***

I NEXT SAW Josie the weekend after Thanksgiving, when I was back in Long Beach to visit family. We chose a sandwich shop by the pier. The day was warm, though overcast, and we took our food down to the water and sat in the sand. I told her I came here often growing up. Nana would take me to play in the waves. We always parked in the same lot that dispensed gold dollars as change from the meters, and she would give me one to bring home. I would put it in a small cloth bag with the others, hidden at the back of my closet, where they would sit, unspent, waiting. I still have that bag, though I haven’t seen it for years.

Josie told me the story reminded her of our conversation before I left. She said memory seems to survive through people and stories as much as place. If home requires time, as I had argued earlier, and if memory is how we preserve time, then the best we can do is gather and speak.

Fog had thickened over the ocean. We balled our wrappers together to thwart the pull of wind. Don’t you think, she asked, that this is your home, here with family? I said I had forgotten about the bag and the coins until just now, returning to the beach. Movement reshuffles memory, divides us from place and history.

Then it follows, she said, that the best thing a placeless person can do is stay put.

You might be right, I said, but for many of us it could be too late, or too inconvenient. I described the autopsy on the calf on the ranch I now worked in southern Arizona. I recounted my morning killing trees—grass, soil, Spaniards, petroglyphs, tombstones, rock-house ruins. I said I wondered what Bloody had thought, chatting with me, a foreigner, while commemorating his deceased kin, engulfed by the song and dance of his ancestors, feet planted on tribal earth.

Let me ask you something, she said. What killed the heifer? Pneumonia, I said. And those trees—did you get the rain you needed? I said we got the rain, but I had departed for a new ranch before the trees had died.

***

RAY AND I loaded our horses and trailered to the old family homestead at the base of the mountains. Established by Ray’s great-grandfather, the building served as ranch headquarters at its founding in 1895. Today we live in the flats below, but the homestead, a melting, bat-infested adobe, endures as the best work base during the winter, when our herd grazes the slopes and canyons of the mountain range. Ray and I planned to ride in search of newborn calves. It was our job to find them and move them, along with their mothers, to lower country, away from mountain lions, where we can keep better watch.

RAY AND I loaded our horses and trailered to the old family homestead at the base of the mountains. Established by Ray’s great-grandfather, the building served as ranch headquarters at its founding in 1895. Today we live in the flats below, but the homestead, a melting, bat-infested adobe, endures as the best work base during the winter, when our herd grazes the slopes and canyons of the mountain range. Ray and I planned to ride in search of newborn calves. It was our job to find them and move them, along with their mothers, to lower country, away from mountain lions, where we can keep better watch.

We were easing along the washboard road, through muted groves of palo verde and mesquite, when we noticed a fresh set of tracks. Large, heavy, probably a rogue bull. We continued another half mile, then stopped at the camp of a hunter. Have you seen any cattle around here? Ray asked. No, the hunter said, he hadn’t seen anything. But his friend had shot a white-tail that morning. He showed us the picture on his phone, a handsome eight-point buck cradled in camouflage arms. Wow, Ray said. Oh that ain’t nothing, the hunter said. His friend who killed the buck was visiting from Pennsylvania; he owned a deer farm where they raised 18-, 24-pointers. It’s all AI, stem cells, that crazy shit, said the hunter. For those Texas millionaires who pay to shoot a trophy to hang on their walls. He swiped on his phone and a photo appeared of a taxidermied buck. It looked as if four separate racks had been grafted to its head. They raise deer for venison too, he said. For the rich folks in New York, they’re paying $95 for a venison dinner.

Well, it was nice chatting with you, said Ray; glad you guys got something. Yeah, the hunter said, I’ve had good luck here. Always seem to find those white-tail two-thirds up the mountains.

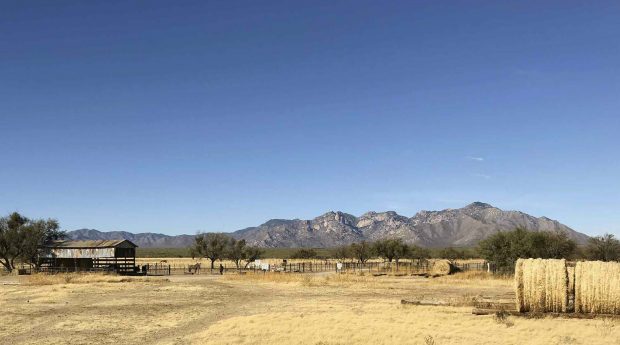

Ray and I drove on to the homestead. We parked beside the old mesquite corrals—corroded, in need of repair—and unloaded our horses. He chose the north canyon. I rode south to the top of the nearest ridge and paused to search for movement or the auburn smudge of Red Angus. Nothing. The slopes were dense with brush, mottled by rock, perfect cover for hiding cattle. I could make out the white cross in the family cemetery below, and see the reflection of water in the original pila, which was now pumped by an array of solar panels. I raised my binoculars and surveyed the distant flats: tanned hide of earth, taut and dry, home for someone, or home enough.

I crossed the ridge and dropped into the far canyon. I threaded between cholla and ocotillo, the stomped pads of prickly pear discarded by munching cattle, and emerged in the wash at the canyon’s center. A few cows, but no calves.

Ray met up with me deeper in the mountains, just beyond the site of a crumbled concrete foundation where a house once stood. Are there any Indian ruins out here? I asked. Those are Indian ruins, he said. I bumped my reins and twisted in my saddle, peered back through the brush for a better view. You know what I mean, I said.