photo by Jewel Samad / AFP / Getty Images

The widow of.

The phrase travels with her through life, as if it were part of her name.

“Widow of Medgar Evers to Deliver Inaugural Invocation,” said a recent headline in The New York Times.

“Widow of Medgar Evers to Deliver Invocation at Obama Inauguration,” said the Washington Post.

“Medgar Evers Widow Gives Inaugural Invocation,” says the YouTube video.

Fifty years have passed since the hot June night in Jackson, Miss., that she heard the crack of a gun then bolted out of her bedroom, followed by her three children, and fell to her knees next to her husband, who lay near the doorstep in a pool of blood.

Within an hour, she was the widow of.

Myrlie Evers-Williams ’68 has tried to be the very best widow Medgar Evers could have hoped for. She has devoted herself to bringing his killer to justice, to keeping the cause of civil rights alive. But in the past half century, she also has maintained another struggle—to become fully realized and recognized as herself. Just Myrlie.

“I made a decision,” she said one balmy winter day when I went to visit her at her apartment in a senior community just outside of Claremont.

The decision she was announcing wasn’t on par with others she had made recently, like selling her big house in Bend, Ore., or squeezing into a tight red dress to play piano at Carnegie Hall with Pink Martini, or agreeing to stand next to the black president of the United States and deliver the inauguration prayer.

This was a smaller act of liberation.

“I’m going to keep my hair natural,” she said, with a deep laugh. “I don’t have time for blow drying and curling and styling. I prefer to let the personality of yours truly emerge.”

On that day in early January, Evers-Williams, a tall woman with a rich voice whose friendliness carries a dash of tartness, felt under siege. She was recovering from the flu. Her sunny one-bedroom apartment was stuffed with boxes and her days were packed with chores.

The inaugural staff kept calling, and she had preparations to make for a 50th anniversary commemoration of Medgar Evers’ assassination.

“I am juggling a life that is not mine,” she said. “You know, as I approach 80, I ask myself why, why are you doing this?”

OK, why?

She plunged her hands into the pockets of her jeans.

“It’s just me,” she said. “It’s the nature of Myrlie.”

A few days earlier, trying to get organized for her upcoming appearances, she had fished some old documents out of the boxes in her living room. She sat down, in one of her orange wing chairs, and began to read about the funeral of the man she had married at 18 and lost at 30.

She was freshly struck by what he meant, to American history and to her. It had been a long time since she wept over Medgar, but sitting there, alone in the clutter of the past, she cried.

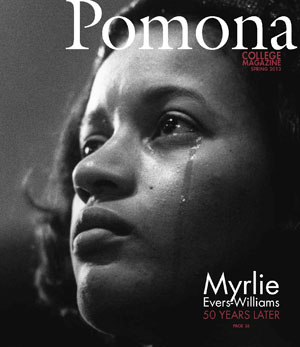

This powerful photo of Myrlie Evers-Williams ’68 (by Flip Schulke/Corbis) taken at a memorial service after her husbands assassination in June 1963 appears on the cover of our spring issue.

TO GRASP the improbable sweep of Myrlie Evers-Williams’ life, you have to understand the place she came from.

Mississippi in 1933 was poor, even by the standards of the Great Depression. In its small towns and out on the sharecroppers’ fields where blacks and whites alike struggled to eke a living from the land, the myth of white supremacy flourished as hardily as Delta cotton.

Like the rest of the Deep South, Mississippi abided by Jim Crow, a set of laws and customs that segregated blacks and whites in public places. Black people were shunted into separate schools and corralled in the backs of buses.They drank from water fountains marked “colored.” When they were allowed in “white” movie theaters, it was through a side door, then on up to “the buzzard’s roost” in the balcony far from the white patrons and the screen.

In that era, in the Mississippi River town of Vicksburg, lived a schoolteacher named Annie Beasley.

Beasley was one of the lucky few, a black woman who had gone to college for a while, and she believed that education was salvation. Shortly after her son and a 16-year-old girl gave birth to a child, she knew what she had to do.

She brought the baby, Myrlie, home.

Beasley owned her own house, a whitewashed place up the hill from the shacks where the poorest blacks lived. In her clean rooms, with the vegetable garden and fruit trees out back, she kept books. She listened to classical music and on Sundays wore white gloves to church.

Myrlie, named after an aunt who also helped raise her, called her grandmother “Mama.”

“Open your mouth and speak distinctly,” Mama instructed Myrlie.

“Baby,” Mama told her, “you may not have the money to travel, but as long as you can read, and books are accessible to you, you can travel anywhere in the world.”

“Baby, baby, get back here,” Mama would call if Myrlie left her nightly prayers too early. “You didn’t ask God to make you a blessing.”

Myrlie Beasley didn’t grow up feeling inferior or poor, and not until she was ready for college did she register how high and hard the wall of segregation was. When she applied for a state scholarship, hoping to study music at a college outside Mississippi, she was told that she could find everything she needed at a black school right there at home.

In 1950, she enrolled at Alcorn A&M College out in the woods of tiny Lorman, Miss.

“Stay away from the servicemen,” Mama and Aunt Myrlie warned.

On her first day at Alcorn, as she leaned against a lamppost, a football player approached. He was a few years older, one of the black Army veterans who had come home to Mississippi after World War II, having tasted the possibilities of the wider world. He was from the little Delta town of Decatur. His name was Medgar Evers.

They married the next year. She was 18.

Medgar Evers got a job selling insurance, and as he drove the Delta peddling his policies, he witnessed daily, in growing dismay, the black sharecroppers who lived barely better than slaves. He loved Mississippi, but in the nascent civil rights movement, he saw a chance to change it.

In 1954, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People hired Evers as its first Mississippi field secretary. He roamed the state, documenting lynchings and other brutalities against black people, helping blacks register to vote, organizing boycotts and sit-ins. At one point, he handed out bumper stickers that read, “Don’t buy gas where you can’t use the restroom.”

Myrlie Evers worked as his secretary while she raised the children. They both grew tired, and scared. They argued, about money and safety. Civil rights was risky business.

In 1957, the Evers family moved up in the world, and into a small new house, with a mortgage, in a stable black neighborhood in Jackson. Some of their neighbors didn’t want them. Medgar Evers was stirring up trouble. Trouble was bound to follow him home.

On June 12, 1963, just past midnight, a few hours after President John F. Kennedy gave a televised speech in support of civil rights, Evers pulled into his driveway. He stepped out of the car, carrying T-shirts that said “Jim Crow Must Go.” From a honeysuckle thicket across the street came a bullet. It pierced him in the back.

“His murder was eerie and providential, so flushed with history as to seem perversely proper—shot in the back on the very night President Kennedy embraced racial democracy as a moral cause,” the historian Taylor Branch wrote in his Pulitzer-Prize-winning book Parting the Waters.

“. . .White people who had never heard of Medgar Evers spoke his name over and over, as though the words themselves had the ring of legend.”

Not all white people.

A proudly racist and cockily unrepentant fertilizer salesman named Byron De La Beckwith was soon arrested, tried twice in 1964, and both times let go after the juries, composed entirely of white men, deadlocked.

THAT SUMMER Myrlie Evers packed up her life and headed for Claremont, Calif., about as far from Mississippi as a car and her imagination could take her.

“The kindness of people in Claremont was beyond belief,” Evers-Williams said, sitting in her apartment all these years later. “That was not what I wanted. I wanted the nastiness, the hatred. I wanted a fight. God, I wanted a fight so bad.”

Medgar had always told her that if they ever left Mississippi, he’d like to go to California, and in Kiplinger’s Magazine, she read a story on the country’s best small colleges. A name caught her eye: Pomona.

Then there she was, the famous widow of the newly famous Medgar Evers, living a continent away from friends and family, in a pruned and placid college town where blacks were almost as rare as snow.

She hadn’t comprehended how white her new hometown was. She had imagined it was more like the neighboring city of Pomona, and some of the black people there were miffed that she’d chosen insular, collegiate Claremont. Did she think she was too good for them?

Not only was she black in a land of whites, but as a 32-year-old student, she was old in the kingdom of youth.

She remembers her first day on campus, some professor addressing the freshmen about what an important time in life this was.

“Why am I sitting here?” she fumed to herself, “when I have three kids at home and I have no idea what they’re doing?”

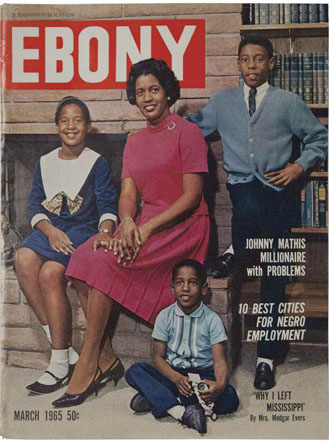

Her arrival in Claremont made news. Look Magazine photographed her poring over her books. Ebony Magazine put her and the three kids on its cover, posed next to their big stone fireplace, all smiles, dressed like the era’s perfect white sitcom families, only without the dad. Inside is a story: “Why I Left Mississippi,” by Mrs. Medgar Evers.

Her arrival in Claremont made news. Look Magazine photographed her poring over her books. Ebony Magazine put her and the three kids on its cover, posed next to their big stone fireplace, all smiles, dressed like the era’s perfect white sitcom families, only without the dad. Inside is a story: “Why I Left Mississippi,” by Mrs. Medgar Evers.

Little by little, she softened to the kindness around her. Masago Armstrong, the Pomona College registrar, was among those who took a special interest.

“She and others were so powerful,” Evers-Williams said. “So powerful in their excellence, making me think about what I wanted to do.”

But the work was hard. Her grades weren’t good. She walked into a professor’s office one day—“Alvin?

Was that his name?”—and announced, “I quit.”

Go home, he said. Put your books away. Come back in a week. She came back in a week, ready to keep going.

When the Pomona College class of 1968 paraded across a stage to collect their diplomas, Myrlie Evers, sociology major, was there. The audience rose and cheered.

“Why did they stand up to applaud you?” her older son, Darrell, asked afterward. “You didn’t do anything different from the other graduates.”

“IS THAT the pool?” she said.

We were standing in front of Sumner Hall, out for a tour of the Pomona campus, where Evers-Williams rarely comes these days. She peered toward the blue shimmer in the distance. Pendleton Pool. She remembers that. Shivering in the water, clinging to the side, afraid, listening to the swimming instructor, Anne Bages, who finally, one day, said, “Myrlie, you must do this. Come on. If your child were on the other side drowning, what would you do? Envision it.”

She envisioned it and swam across the pool. “Her patience, her strength and determination to see I did what I had to do,” Evers-Williams said, “that speaks to my entire experience here.”

It was a sunny, warm day, and as we walked past Little Bridges, she remembered that old, elegant, mission-style building, too. She and her second husband, a longshoreman and union organizer named Walter Williams, were married there in 1975, before they set off for a life in Oregon.

“He was my dearest best friend,” she said. Williams died in 1995. “He was so good to me and my children.”

She walked on, slowly, wishing she’d brought her cane.

“God,” she said, “I’ve lived through so many changes. It’s amazing to walk on this campus and think of it. Mind if we sit?”

We sat on a bench on Marston Quad, looking toward Mount Baldy, past the trees that never seem to change. She thought back. Her eight years as an executive at Atlantic Richfield Company. Her run for Congress, unsuccessful but a decent showing. Her three years in the mid-1990s as head of the NAACP; she has some untold stories she’d love to tell about that. The writing, the speaking. The three children brought successfully to adulthood. “When I look at my bio,” she said. “I say, ‘wow.’”

Through it all, she never forgot that she was the widow of. She kept her eye on that cocky fertilizer salesman, Byron De La Beckwith. Her pressure helped persuade the state of Mississippi to retry him, and in 1994, a racially mixed jury of Mississippians declared him guilty of Medgar Evers’ murder.

There were many times after Medgar Evers died that his widow cursed and cried and wanted to dwell in hatred. She built a different life instead.

“And now?” she said. “Back in Mississippi after 50 years.”

Last February, while keeping her apartment near Claremont, she returned to Alcorn State University as a visiting scholar. “Come home,” she says the president of the college told her. “Come home and let us take care of you.”

So she went, and flew into Jackson-Medgar Wylie Evers International Airport.

In this half century, Evers-Williams has never ceased to be surprised.

Another surprise arrived after she gave a TEDx talk in Oregon a while back. She told the audience about how as a girl in Vicksburg, she sang and played the piano, and how her grandmother and aunt dreamed she would make it to Carnegie Hall. Out in the crowd that day sat Thomas Lauderdale, the founder of the pop orchestra Pink Martini. Afterward, he made her a proposition: Come perform with us. At Carnegie Hall. Crazy, she thought. Not with her arthritic fingers, and besides, she didn’t play much anymore. And, really, she was shy.

Then she thought of how Medgar used to say, “Trust yourself.”

She said “yes.”

One night last December, at the age of 79, she swept onto the New York stage in a form-fitting red dress— “long trumpet sleeves, just a little bit of cleavage and this gorgeous train”—tailored for her by the designer Ikram.

She sat down at the baby grand, so unlike the cold, out-of-tune piano at Alcorn that she’d been practicing on.

She played “Claire de Lune,” her grandmother’s favorite, followed by “The Man I Love.”

The audience gave her a standing ovation.

“As ‘the widow of,’” she said later, “I kept Medgar’s memory alive, and that’s what I was determined to do. But there is the Myrlie who at times finds herself saying, ‘Hey, wait a minute, I’ve done these things too, on my own.’ That’s one reason I got such a kick out of Carnegie Hall.”

Soon after her Carnegie debut, she would be at the inauguration, standing next to the first black president of the United States, praying aloud for the nation, the personification of its past, its progress, its hope.

“People choose, I think, what they want to be,” she said that day in Claremont, closing her eyes for a moment, soaking up the sun. “I don’t believe in self pity forever.”

Her mind flitted back to her old friends, Coretta Scott King, widow of Martin, and Betty Shabazz, widow of Malcolm X. She recalled a newspaper story a young woman once wrote about the three of them.

“The article was: these are just widows living off their husbands’ reputations,” she said. “Betty, Coretta and I talked, furious. Coretta said, in her calm, understanding way, ‘Oh, she’ll learn, she’ll learn.’”

Evers-Williams sighed.

“I miss those two ladies so much.”

At 80, there are many people for her to miss. Mama, Medgar, Walter, Aunt Myrlie, her mother and father, her son Darrell, who died nine years ago of cancer. She feels their absence but looks for the blessings.

Every morning when she gets up, she walks into the bathroom and before brushing her teeth or washing her face, she performs a ritual that shapes the day.

“Hi, beautiful,” she says to the mirror, and she smiles.