I.

I Fly to Austin to Visit an Archive of the Entire Works and Life Papers of My Writing Mentor and Once Professor

The great thing about being a writer is that you send out vague emails like the one I sent asking the editor of this magazine if he had any work for me, and sometimes something wonderful, and completely beyond the value of money comes back. That was what happened when the editor of this magazine asked me if I might want to go to Austin to spend some time with the papers of David Foster Wallace who, despite my complicated feelings around his death, remains the most influential writer and perhaps more importantly, teacher, in my life.

A few weeks later, I was flying to Austin on-schedule through sheets of unbroken blue spotted with perfect clouds reminiscent of the original cover of Infinite Jest.

II.

The First Time I Encountered David Foster Wallace, the Writer

I found that blue-sky book in my father’s office in our house in 1996, opened it and didn’t leave my bed for five days. I was 15. I can’t remember whether I was actually sick or just decided to stay home “sick” from school for a week so I could do nothing but read Infinite Jest from morning until night.

I found that blue-sky book in my father’s office in our house in 1996, opened it and didn’t leave my bed for five days. I was 15. I can’t remember whether I was actually sick or just decided to stay home “sick” from school for a week so I could do nothing but read Infinite Jest from morning until night.

All I know is that absorbing those words for the first time, for me, was a kind of transport as real as the flight I took from JFK to Austin. It was more than half my life ago, but I still have a very visceral memory of the days I shared with that book in my bed in my sophomore year of high school. I remember those days reading Infinite Jest in flashes, as if they were sections of a scary and wonderful trip I took by myself away from the teenage high school place I was stuck in at that time and so longed to escape, and into a terrain far more sophisticated and complicated. It was the kind of journey that, even though it had to end, when I got back I was permanently changed, and I knew it. Another way to say this would be that in adolescence, before I stumbled upon Infinite Jest, I was sad, but I thought the sadness I felt was unique to me, and that made me sadder. After reading Infinite Jest, I realized that there was a vast, great, adult sadness in the world that I was only likely experiencing the very tip of at that particular adolescent moment, and that made me feel significantly less sad.

I know now that many people feel that sense of both change and of having their specific sadness understood and put to words for the first time when they first read the work of David Foster Wallace. I didn’t know it then. I just knew that despite being an insatiable reader since I could put letters together, I finally had a favorite author.

III.

The First Time I Encountered David Wallace, the Professor

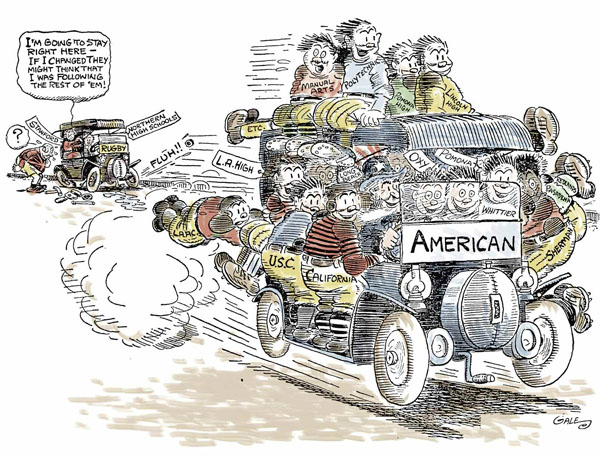

By the time I arrived at Pomona in 1999, I had read all of David Foster Wallace’s books that he had published up to that time except one and loved and was likely changed by them all. (The one book I hadn’t read was Signifying Rappers: Rap and Race in the Urban Present, because it was harder to get, and still is. I should probably still get it.)

I met David Wallace the person and professor in 2002, in the fall semester of my senior year. I had just returned from taking the previous semester off. During my semester off, I hiked the Appalachian Trail. I walked from Georgia to Maine, over 2,000 miles. I was struggling with a lot of things that now, as a professor, I understand are not uncommon for college students to struggle with. At the time, however, I thought my struggles meant I might not come back to Pomona in the fall when and if I finished my epic hike. I felt like maybe I wasn’t in the right place to be in college, or that college maybe wasn’t the right place for me to be.

I met with my advisor at the time, a professor in the English Department whom I also still admire. I told him that even though I was leaving college to live in the wilderness for six months to walk until I (I hoped) became unrecognizable to myself, I needed all the information he had available so that I could apply to the workshop I’d heard rumors that David Foster Wallace was coming to teach at Pomona in the fall. My advisor then said what many writers I respect have said to me about the writing of David Foster Wallace since. He said he didn’t know what everyone was so excited about, because he thought David Foster Wallace was sophomoric. I told my advisor that I was only a junior, and that when I had fallen in love with the writing of David Foster Wallace I had actually been a sophomore in high school, so that made perfect sense.

A few months later, I mailed in my story to apply to be in Professor Wallace’s Advanced Fiction Writing Workshop from a small outpost in rural Tennessee on the Appalachian Trail. It was the first story I had ever written from beginning to end, and it was about opening my father’s stacks of forbidden journals to find that they were not full of racy life experiences but instead of lists and lists of the books he had read when he was younger. I don’t know if I got into the workshop because the story was any good or if Wallace was just impressed with how battered the envelope was from being lugged around in my pack in the woods. I just know that I wasn’t a writer when I went into his workshop, and I was when I came out.

IV.

I Find Enough Wallace Files to Build a Fort Out of File Folders, No Make That A Whole Empire of Forts, So I Make Some Ground Rules and Start Sifting

There are five “collections” of papers at the Harry Ransom Center that come up if you do a search for David Foster Wallace. Each collection has an average of one to 10 “series,” which are groups of containers. From there, the numbers get complicated. The number of containers in each series varies greatly. The number of boxes in each container also varies greatly. The number of folders in each box—you get the idea.

One way to think of the categorical branching off of the material remnants of Wallace’s life would be like being surrounded by the folds and memory files of a giant, sterile, academic brain. I’m not a neuroscientist, so forgive me for the crudeness of this metaphor when it comes to its scientific roots. But at certain moments, going through those carefully ordered compartments of paper—being in the reading room at the Ransom Center did feel like being inside a brain in the best kind of way. A brain where everything had finally been sorted and smoothed and was organized once and for all to be shared, something I guessed Wallace might have appreciated, at least based on the lamentations about how hard it was to communicate the chaos in one’s head in an orderly way on paper that I was reading over and over as I sifted through those concrete-colored cardboard boxes of correspondence.

Confronted with so much paper, I had to determine what not to write about. After significant deliberation, I decided:

1. I would not write about manuscripts, various versions of manuscripts, or Wallace’s marginalia on manuscripts. I knew this was the kind of undertaking that would require far more time than I had at the University of Texas at Austin. Also, after having Wallace as a professor, I really respect him as a reviser, so I was not that interested in mining earlier drafts.

2. I would not write about Wallace’s correspondence that had to do with pitching his books and other writing. It seemed to me to be the most business part of the files, and I was interested in the opposite.

3. I would not write about his personal correspondence. It was just too sad. Exposing it without permission would feel like a violation. I will say that there were some fun postcards. I left the archive with the resolution to send more postcards, especially when not traveling. Favorites included pulp book covers such as A Woman Must Love: She Thought She Could Live Without Men, a photo of Truman Capote luxuriating at home in a bathrobe and Stetson, and a photo of an old geezer that Wallace had drawn a voice bubble for with the words, “Kein kluger Streiter hält den Feind gering.” I put the line into Google and learned it was a quote by Goethe. Translated, it reads, “No prudent antagonist thinks light of his adversary.”

4. I would not present the reader with just lists—lists of the words Wallace looked up and wrote his own definitions of, lists of the readings he assigned his students. I couldn’t fit those amazing lists into this brief article even if I wanted to. There were too many and they were too long! One folder I scanned of words Wallace wrote the definitions of is 100 pages long. Most of the pages are filled with lists of words in small print and they are on both sides. I hope someone someday publishes a book of his lists: lists of words, lists of recommended readings … I have a feeling someone will … In the meantime, here are a few gems that Wallace looked up the definitions of: vituperations, littoral, oneiric copralalia, tenesmus, gomphosis, coruscate, felo de se, votary, sapropel, nonceword, polyandry, logorrhea, facula, stellify, comether, rimple, hypolimnion and adumbrate. I leave it to you to take to the dictionary to unearth their meanings. One thing is certain about the David Wallace I knew as a student at Pomona, he would want you to work for it.

V.

The Single Most Joyful Thing I Found While Sifting Through the Papers of My Dead Professor

As I returned various boxes to the reference librarian, I slowly realized that what I was most interested in, and what fellow Sagehens were likely to be most interested in, was David Wallace the professor and David Wallace the person. That was how we knew him best after all. I decided to leave David Foster Wallace, fascinating and heartbreaking as he was in the pages I sifted through, to the people who knew him as a writer, in that way while he was still alive—to leave it up to them to decide when and what to

share from that aspect of the archive.

My favorite folder was the folder of the photocopies of the American Heritage Dictionary ballots. Wallace was a member of the company’s board that governed decisions on usage, spelling and pronunciation. The ballots show the feedback he gave to the American Heritage Dictionary over the years on items they sent him to review.

I think I was especially delighted to find Wallace’s dictionary ballots after reading his personal letters to the writer Don DeLillo, many of which seemed tortured or fraught with insecurity and self-doubt, because when Wallace is commenting on the dictionary ballots there is not a shred of that self-consciousness in his obvious joy in interacting so directly with pure language in its most naked state. Whether he is appalled at the way most people don’t understand the meaning of “to beg the question,” or enthusiastically approving the many acceptable different ethnic pronunciations of the words “bayou” or “calzone,” it is clear that there is no terror or stress for him on these pages, only an incredibly exuberant love of the words, stripped down to their barest selves.

Though Wallace may have wrestled with his role as a writer, his role as a grammarian and expert on words was clearly pleasing to him, and carried with it none of the burden of assemblage that creating novels and other texts did. I like looking at these dictionary ballots because, even in this quiet room that I can’t help feeling is a tomb of some kind, his joy and the thrill he got from his expert manipulation of the English language shines through.

When I reach the end of the folder of dictionary usage ballots dated 11-04-05, I get a pang seeing that he has listed a permanent change of address to Claremont, California, after he had already lived there three years. The address snaps me out of the paper and back to thinking about how difficult it is to reflect, on the one hand, about your friend whom you admired, who died, and on the other, about the intersection of your somewhat normal life with the life of someone whose papers end up in an archive … it’s difficult and disorienting to try to reconcile the two.

I only knew one very specific and cordoned-off part of David Wallace. Being confronted so closely with the other parts, having access to so many of them, felt reckless and unnatural, almost as if I was traveling through time. At points, I had to remind myself that Don DeLillo is still alive—that the dictionary ballots I was looking through were filled out by Wallace two years after I graduated from Pomona, only eight years ago. Retrieving them from those files in the archive where the papers of other great thinkers, long dead, were kept changed them somehow. It made him feel less like a person or friend, and more like a dead great writer.

VI.

There are More Than 40 Bronze Busts of (Predominantly White Male) Authors in the Harry Ransom Center, and a Bust of David Foster Wallace is Not Yet Among Them

There is an epigraph printed on the wall as you enter the reading room where you go to request the files. It is cited only as coming from the Hebrew Union Prayer Book. It reads, “So long as we live, they too shall live, for they are now a part of us, as we remember them.”

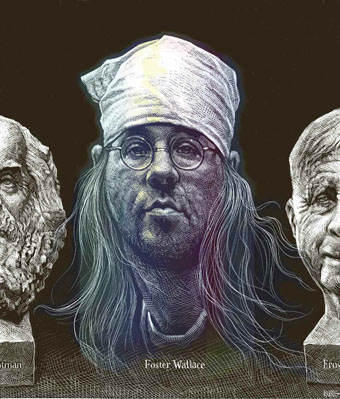

There are also the busts of great dead authors everywhere, immortalized in bronze inside the reading room, on the halls leading up to it and on the floor below where you enter the building that is designed to protect the delicate remembrances of great men from excesses of heat or light. Unfortunately, the busts are mostly old white men, which makes me start to wonder about the obvious question.

Who decides who gets a bust?

I walk around photographing all the bronze busts, metal, immortal monuments to other “great” authors (photographing is a way of looking when you are in an archive trying to absorb as much as possible). It is only when I get to the last one that I realize I had been hoping to find a bust of Wallace. There isn’t one. At least not yet.

Some of the authors get more than one bust inside the Ransom Center. There are three James Joyces, two Hemingways, two George Bernard Shaws. Steinbeck’s mustache is sculpted in a way that makes him look like a bullfighter, Tom Stoppard’s bust looks an awful lot like Mick Jagger, the two women who have been chosen above all the rest seem to be somewhat randomly Edith Sitwell and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Sitwell’s bust is also the only one that isn’t at least somewhat realistic. The rendering of her head as a giant, balloon-ish, moonlike white marble sphere with enlarged, alien eyes is eerily out of place, as if, in the afterlife, only her soul out of them all is not shaped like a person.

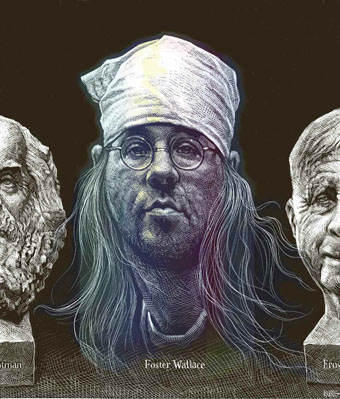

Perhaps someday there will be many busts to represent the many David Wallaces. The wacky young Wallace, eternally bandana-ed. The junior tennis pro. The fat, sweaty Wallace I saw read as a sort of audition for the post he came to fill the following year, significantly more svelte. The drug-addicted atheist and the sober Christian. It’s possible bronze is too ancient a material to capture a personality with so many genuine permutations. The future is long. Maybe someone will commission a hologram. Then, perhaps, the next time I come to visit these papers (I suspect there will be a next time), between the busts of Whitman and Frost, there will be a simulacrum of my old professor, made of light, chewing tobacco and spitting it into an old, dirty peanut butter jar, just as he used to do in class.

On a 70-degree, late-November day, Ian Gallogly ’13 and Rob Ventura ’14 are sitting in the courtyard of the Smith Campus Center and talking hockey.

On a 70-degree, late-November day, Ian Gallogly ’13 and Rob Ventura ’14 are sitting in the courtyard of the Smith Campus Center and talking hockey. The women’s soccer team reached the finals of the SCIAC Tournament for the first time in school history with one of the biggest upsets of the fall season, knocking off top-seeded Cal Lutheran 2-1 in overtime in the semifinals, before losing to Chapman 4-1 in the finals. Julia Dohner ’16 had both goals for the Sagehens in the semifinals, after the team needed to rally late in the regular season to qualify. A 1-0 home win over Redlands on the first career goal from Natalie Barbaresi ’16 put the Sagehens in position to qualify, and a goal from Claire Mueller ’13 in a 1-0 win over La Verne in the season finale put Pomona-Pitzer in the postseason for the second year in a row. Jordan Bryant ’13 and Allie Tao ’14 were named first-team All-SCIAC and earned a spot on the NSCAA All-West Region team as well.

The women’s soccer team reached the finals of the SCIAC Tournament for the first time in school history with one of the biggest upsets of the fall season, knocking off top-seeded Cal Lutheran 2-1 in overtime in the semifinals, before losing to Chapman 4-1 in the finals. Julia Dohner ’16 had both goals for the Sagehens in the semifinals, after the team needed to rally late in the regular season to qualify. A 1-0 home win over Redlands on the first career goal from Natalie Barbaresi ’16 put the Sagehens in position to qualify, and a goal from Claire Mueller ’13 in a 1-0 win over La Verne in the season finale put Pomona-Pitzer in the postseason for the second year in a row. Jordan Bryant ’13 and Allie Tao ’14 were named first-team All-SCIAC and earned a spot on the NSCAA All-West Region team as well.

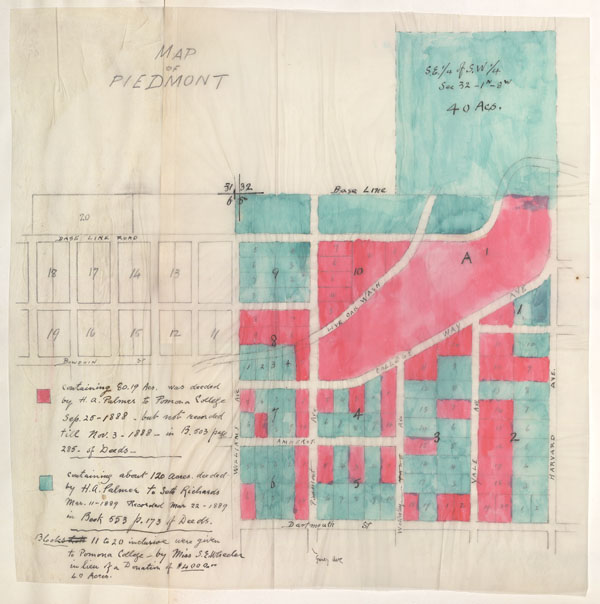

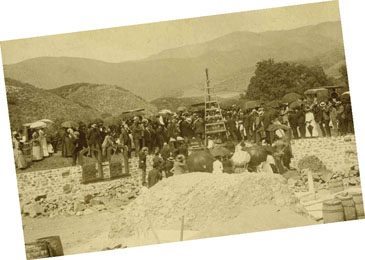

There remained, however, a photo from the September day in 1888 when hundreds of people gathered at the base of the foothills north of Pomona for the cornerstone ceremony. That old black and white helped lead me back to the spot known as Piedmont Mesa and its faint traces of the College’s beginnings.

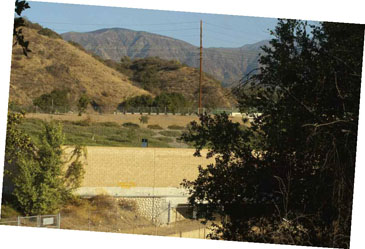

There remained, however, a photo from the September day in 1888 when hundreds of people gathered at the base of the foothills north of Pomona for the cornerstone ceremony. That old black and white helped lead me back to the spot known as Piedmont Mesa and its faint traces of the College’s beginnings. Even on the little screen, it was easy to line up the old view with the present one, since the hills had changed so little in 125 years. Comparing the two views, it looked to us like the site of the original cornerstone—later relocated—might just lie beneath the 210 Freeway, which today slices through the site.

Even on the little screen, it was easy to line up the old view with the present one, since the hills had changed so little in 125 years. Comparing the two views, it looked to us like the site of the original cornerstone—later relocated—might just lie beneath the 210 Freeway, which today slices through the site.

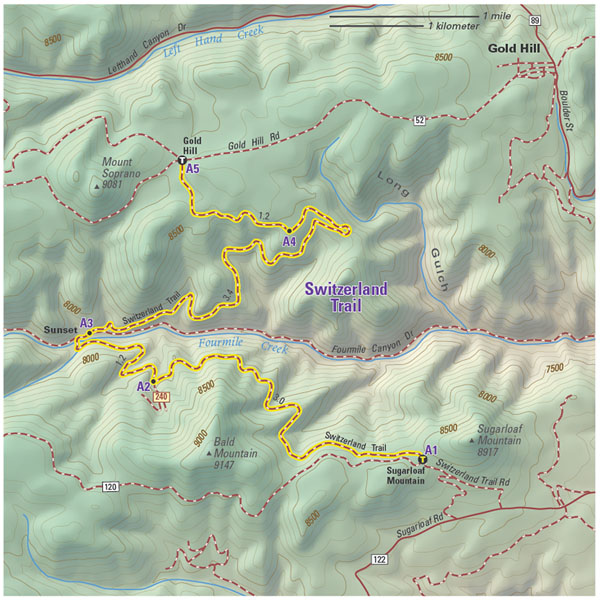

Fortunately, he was able to include some of the historical tidbits—along with 118 maps—in his recently published book, The Mountain Biker’s Guide to Colorado (Fixed Pin Publishing). Hickstein is now a fourth-year grad student at University of Colorado, where he studies how ultrafast lasers can be used to make super-slow-motion movies of chemical reactions. But after a long day in the lab, Hickstein still finds time to ride the trails, sometimes even bringing along his own tome and its trusty maps.

Fortunately, he was able to include some of the historical tidbits—along with 118 maps—in his recently published book, The Mountain Biker’s Guide to Colorado (Fixed Pin Publishing). Hickstein is now a fourth-year grad student at University of Colorado, where he studies how ultrafast lasers can be used to make super-slow-motion movies of chemical reactions. But after a long day in the lab, Hickstein still finds time to ride the trails, sometimes even bringing along his own tome and its trusty maps.

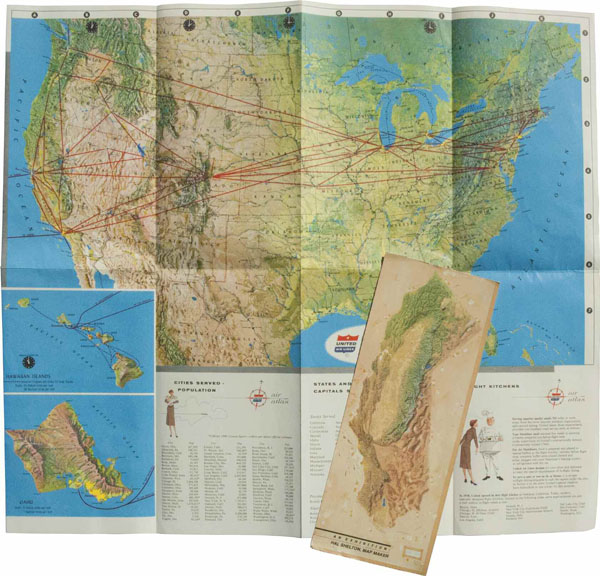

If the natural color concept seems straightforward—forests are green, deserts are brown— the execution required patience, skill and considerable expense. Decades before satellite imagery was widely available, Jeppesen hired academic geographers to gather the data, which was etched into zinc plates about two to three feet in diameter. Working on an inch at a time, Shelton then painstakingly painted on the landscape features along with shaded relief to show elevation. His artistry yielded “realistic picture maps that astound the cartographic world,” as The New York Times gushed in 1954.

If the natural color concept seems straightforward—forests are green, deserts are brown— the execution required patience, skill and considerable expense. Decades before satellite imagery was widely available, Jeppesen hired academic geographers to gather the data, which was etched into zinc plates about two to three feet in diameter. Working on an inch at a time, Shelton then painstakingly painted on the landscape features along with shaded relief to show elevation. His artistry yielded “realistic picture maps that astound the cartographic world,” as The New York Times gushed in 1954.

I found that blue-sky book in my father’s office in our house in 1996, opened it and didn’t leave my bed for five days. I was 15. I can’t remember whether I was actually sick or just decided to stay home “sick” from school for a week so I could do nothing but read Infinite Jest from morning until night.

I found that blue-sky book in my father’s office in our house in 1996, opened it and didn’t leave my bed for five days. I was 15. I can’t remember whether I was actually sick or just decided to stay home “sick” from school for a week so I could do nothing but read Infinite Jest from morning until night.

The weight of it finally hit him, Brian Schatz ’94 says, when he woke up from a rest on Air Force One, bound for the nation’s capital, in the early morning of Dec. 27. A day before, Schatz had basked in the warm breezes of Honolulu, where he served as Hawaii’s lieutenant governor, a role with few expectations compared to the one he was about to begin.

The weight of it finally hit him, Brian Schatz ’94 says, when he woke up from a rest on Air Force One, bound for the nation’s capital, in the early morning of Dec. 27. A day before, Schatz had basked in the warm breezes of Honolulu, where he served as Hawaii’s lieutenant governor, a role with few expectations compared to the one he was about to begin.

And yet, during much of the 20th century, with the ascendancy of behaviorism in both human and animal psychology, it was strictly taboo in most scientific circles to speak of animals having minds or feelings. The very idea was mocked as anthropomorphic thinking—that sentimental human tendency to project our own motivations onto things around us, from the balky station wagon that won’t start to those vicious weeds that invade our garden each summer. Even Darwin, who, in his time, speculated freely about the cognitive abilities of all sorts of animals, from lizards to apes, was considered naive in this regard. And so, for much of the century, science moved forward in the unshakable conviction that not only was animal thought and emotion unknowable; it was out of the question. Animals did not love.They did not suffer. They did not think or plan or communicate in meaningful ways.

And yet, during much of the 20th century, with the ascendancy of behaviorism in both human and animal psychology, it was strictly taboo in most scientific circles to speak of animals having minds or feelings. The very idea was mocked as anthropomorphic thinking—that sentimental human tendency to project our own motivations onto things around us, from the balky station wagon that won’t start to those vicious weeds that invade our garden each summer. Even Darwin, who, in his time, speculated freely about the cognitive abilities of all sorts of animals, from lizards to apes, was considered naive in this regard. And so, for much of the century, science moved forward in the unshakable conviction that not only was animal thought and emotion unknowable; it was out of the question. Animals did not love.They did not suffer. They did not think or plan or communicate in meaningful ways.