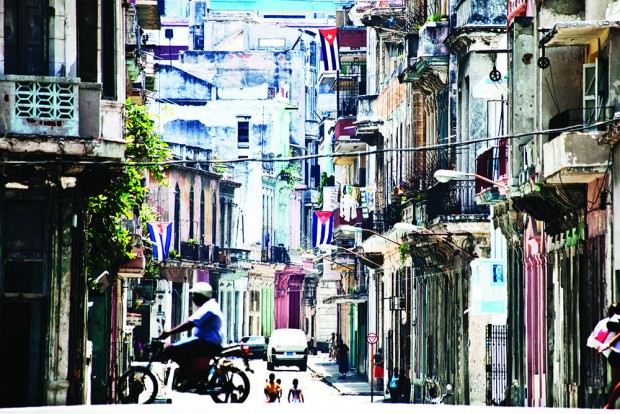

Photo by Michael Larsen ’89 and Tracy Talbert

How do you look a man in the eye and ask him for a million dollars on national television?

“You have to just go for it and not think about it,” Justin Fenchel ’06 says. “As soon as anyone in the room senses weakness, you’re doomed.”

It was June of 2014, and Fenchel was talking shop with Mark Cuban, owner of the Dallas Mavericks and one of the judges on the ABC reality show “Shark Tank.” Cuban had just bid $600,000 to buy a third of Fenchel’s company, and eight million TV viewers were waiting for an answer.

Running the numbers in his head, the Pomona economics major was hesitant to say yes. His team had agreed beforehand that they wouldn’t give up more than 20 percent of the business unless they received a particularly hefty bid.

The room was suddenly eerily quiet. The show’s dramatic background music wouldn’t be added for several more months, and the bright studio lights were making Fenchel feel like he was about to black out. (Looking at the transcript afterwards, he says, “I don’t remember half of the comments I appear to have made.”)

One thing he did recall saying, though, was his reply to Cuban: “Would you do a million?”

Cuban paused a beat.

“Sure.”

With those four letters, Fenchel’s life changed in a very big way.

BeatBox Beverages, his line of wine-based cocktails that come in blindingly bright 5-liter boxes, had just been valued at three million dollars, and was about to experience the unique joy that is “the Shark Tank effect.”

After not being stocked in a single store 18 months earlier, BeatBox soon expanded to nearly 900 locations in 13 states, all while grabbing celebrity endorsements and positioning itself to take on the biggest players in the wine world.

Reflecting on BeatBox’s rapid rise, Fenchel shakes his head and grins sheepishly.

“To think,” he says. “It all basically started with a game of ‘slap-the-bag.’”

Boxed-Wine Beginnings

Like Facebook and Napster before it, the origin story for BeatBox quite literally begins in a dorm room.

One of Fenchel’s fondest Pomona memories was living in the North Campus trailers and hosting “boxed-wine Tuesdays,” where his roommates would buy a case of Franzia wine and invite friends over to watch movies. His Pomona years coincided nicely with the rise of “slap-the-bag,” a drinking tradition that involves removing a bag of wine from its box, slapping the side of the bag, and taking a swig right from the nozzle.

Fenchel enjoyed the communal nature of “slap-the-bag,” and found Franzia convenient, affordable—and completely boring.

“The only reason I bought it was because there wasn’t a more appealing option,” he says. “It made me wonder if I could take the idea of a boxed wine, and recreate it so people my age would actually be excited to bring it to a party.”

After college he and his childhood friend Brad Schultz collaborated on a few iPhone apps, while still kicking around drink ideas.

In 2011 they dreamt up “Wine-ergy,” a caffeinated beverage coming in flavors like “Call-A-Cab” and “ZinFUNdel”; they promptly nixed the concept after the caffeine-infused Four Loko courted controversy on college campuses. A few months later they mulled over a vodka-based drink, before learning that regulations on spirits would limit their “party in a box” to a decidedly un-party-like 12 servings.

What finally kick-started BeatBox was, of all things, a glass of OJ. Specifically, Fenchel stumbled across a special wine made of oranges that drinks more like a spirit and pairs deliciously with fruit juice. By 2012 he had built a team of co-founders and developed flavors that were directly inspired by his days making Crystal Light and vodka mixers at Pomona.

On a bootstrap budget, Fenchel’s team crowd-sourced a logo and package design. To focus-group their product, they would plaster BeatBox stickers onto cardboard boxes, put test batches into empty wine-bags (“Thanks, Franzia!”), and walk around local events giving out free samples.

“We’d go to festivals and ask for brutally honest feedback on which flavors tasted best,” Fenchel recalls. “We knew we were onto something when people were literally throwing 20 dollar bills at us and asking where they could buy it.”

BeatBox’s first production run was just in time for the South by Southwest (SXSW) music festival in March of 2013. Slowly but steadily, the company grew—from 20 cases a month, to 50, to 100, with Fenchel and his three colleagues still packaging and pressing every box.

“By 2014 we had increased our distribution 800 percent, but realized that we were still spending all our time in the warehouse and none of it expanding,” he says. “We needed money.”

Getting in the Tank

Justin Fenchel ’06 and his Beatbox partners on ABC’s SharkTank

Customers had been constantly telling Fenchel that his company seemed ripe for “Shark Tank.” When producers announced an open casting call at SXSW 2014, he stood in line for two hours to give his 30-second pitch. Three months later, BeatBox was one of 108 teams to be selected for the show, out of 70,000 annual submissions. (“You’d have a better chance getting into Harvard, or even Pomona,” Fenchel says.)

The team feverishly prepared in the ensuing weeks, painstakingly researching the show’s five judges and enlisting business faculty from the University of Texas to serve as “mock sharks.” They learned about the sharks’ every move—what they invested in, what they looked for in companies, and even what they ate for breakfast each morning.

“We acted like it was the biggest job interview of our life,” Fenchel says. “Which it was.”

The work paid off: in the months after BeatBox’s episode aired in October 2014, sales doubled and the team expanded from 150 stores to nearly 900. In 2015 they hit a million dollars in sales and rung up endorsements from the likes of electronic musician Skrillex and rapper Waka Flocka Flame, who enthusiastically describes the Blue Razzberry flavor as his “Turnt Up Juice.”

“Shark Tank” also impacted BeatBox in more intangible ways. “It certainly helps when your email to Walmart’s Texas distribution team includes a CC to the most powerful businessman in the state,” says Fenchel, who connects with Cuban at least once a week via email or text. “People who wouldn’t return our calls before were taking meetings with us now.”

As Fenchel zips around the country hobnobbing with potential distributors and investors, one of the most common questions he gets is a simple one: why boxed wine?

As any casual oenophile knows, boxed wine has what Fenchel generously describes as a “perception problem.” The practice of putting wine in boxes first emerged in Australia in the mid-60s, and the cheapness of the approach made it attractive to low-end jug-wine sellers in America.

While companies targeting upscale customers may view the box as a barrier, BeatBox treats it as a key differentiator and marketing tool for millennials who are more interested in having fun than seeming sophisticated.

The box also helps the bottom line, since boxed wine is cheaper to produce, longer-lasting, more convenient and more environmentally-friendly than traditional methods. BeatBox’s sales last year translated to a savings of 530,000 wine bottles that weren’t being produced or trashed.

Justin Fenchel ’06 and his

partners meet with investor

Mark Cuban.

Moving forward, Fenchel’s five-year plan is simple: “More stores, lower costs.” He’s hoping to get big-chain authorizations from the likes of Publix and Kroger, and hopes to soon stock single-serving sizes so that they can sell it at bars and convenience stores.

He also has built a network of more than 250 “brand ambassadors” who organize promotional events and happy hours around the country. It’s all part of his loftier goal to grow BeatBox into a global company on par with Red Bull, with sponsored concerts and sports competitions.

“If anyone can turn BeatBox into a lifestyle brand, it’s the guy who’s embodying that lifestyle,” says Schultz. “The fun-loving, outgoing, celebratory spirit of BeatBox—that’s more or less a direct reflection of Justin and who he is as a person.”

When I was in my early 20s, I briefly dated a young woman who, as I soon discovered, had already planned out her entire funeral. She had it all down on paper—from music to flowers to who would speak when—with corrections and notes in the margins. I suppose that funeral fetish might have had something to do with the fact that we only dated briefly. After all, in our society, thinking too much about death is considered morbid and strange.

When I was in my early 20s, I briefly dated a young woman who, as I soon discovered, had already planned out her entire funeral. She had it all down on paper—from music to flowers to who would speak when—with corrections and notes in the margins. I suppose that funeral fetish might have had something to do with the fact that we only dated briefly. After all, in our society, thinking too much about death is considered morbid and strange.

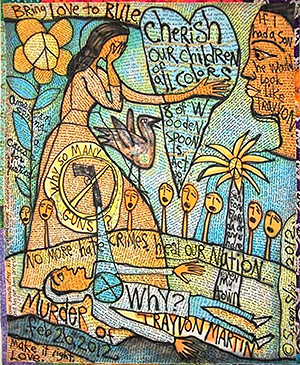

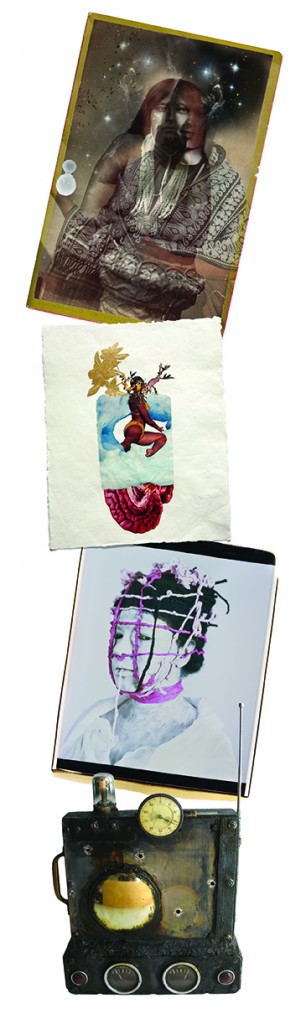

March 6, at Pomona College and Scripps College, invites viewers to contemplate the visceral, spiritual, emotional and political dimensions of diaspora.

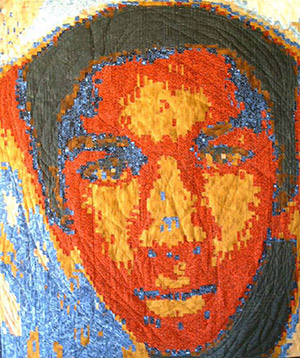

March 6, at Pomona College and Scripps College, invites viewers to contemplate the visceral, spiritual, emotional and political dimensions of diaspora. Florida, will be on display at Pomona College, beginning Feb. 23. The quilts come from the Fiber Artists of Hope Network and reveal reactions to Martin’s death in 2012 and hopes for a better America.

Florida, will be on display at Pomona College, beginning Feb. 23. The quilts come from the Fiber Artists of Hope Network and reveal reactions to Martin’s death in 2012 and hopes for a better America.