(Photos by Mark Wood)

THE EASIEST WAY for non-Texans to get to Marfa, Texas, is to fly into El Paso. From there, it’s a three-hour drive, the kind that turns shoulder muscles to stone from the sheer effort of holding the steering wheel on a straight and steady course for so many miles at a stretch. And when you finally get there, it looks pretty much like any dusty, dying West Texas railroad town. Except for the fact that Marfa isn’t dying at all—in fact, it’s thriving.

You may have heard of Marfa. In the past few decades, it’s gained a kind of quirky fame among art lovers. As a writer with an interest in the arts, Rachel Monroe ’06 was familiar with the name back in 2012 when she set out from Baltimore on a cross-country trek in search of whatever came next. At the time, she assumed the little town was probably located just outside of Austin, but as she discovered, it’s actually more than 400 miles farther west, way out in the middle of the high desert.

After a long day’s drive, Monroe spent fewer than 24 hours in Marfa before moving on, but that brief rest-stop on her way to the Pacific would change her life.

* * *

A NATIVE OF Virginia, Monroe is no stranger to the South, but she never truly identified as a Southerner until she came to Pomona. “I grew up in Richmond, which was, and still is, very interested in its Confederate past,” she recalls. A child of liberal, transplanted Yankees in what was then a deeply red state, she remembers feeling “like a total misfit and weirdo.”

When she got to Pomona, however, she was struck by the fact that most of her fellow first-years had never had the experience of being surrounded by people with very different opinions about culture and politics. “It wasn’t so much that I missed it,” she says, “but I saw that there was an advantage, and that it had maybe, in some ways, made me more sure of myself in what I did believe.”

It was also at Pomona that Monroe started to get serious about writing. Looking back, she credits the late Disney Professor of Creative Writing, David Foster Wallace, with helping her to grow from a lazy writer into a hardworking one. “He would mark up stories in multiple different colors of pen, you know, read it three or four times, and type up these letters to us,” she explains. “You really just felt like you were giving him short shrift and yourself short shrift if you turned in something that was kind of half-assed.”

It was also at Pomona that Monroe started to get serious about writing. Looking back, she credits the late Disney Professor of Creative Writing, David Foster Wallace, with helping her to grow from a lazy writer into a hardworking one. “He would mark up stories in multiple different colors of pen, you know, read it three or four times, and type up these letters to us,” she explains. “You really just felt like you were giving him short shrift and yourself short shrift if you turned in something that was kind of half-assed.”

She didn’t decide to make a career out of writing until the year after she graduated. In fact, she remembers the exact moment it happened—while hiking with some friends in Morocco, where she was studying on a Fulbright award. “I remember having this really clear moment when I was like, ‘I think I want to try to be a writer.’ It was one of those thoughts that arrive in your head like they came from outside of you—in a complete sentence, too, which is weird.”

A year later, she was at work on her MFA in fiction at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, but she wasn’t particularly happy. Her goal was to write short stories, but even as she was churning out stories and entering contests and submitting to journals, she felt like a fraud. “I would get these subscriptions to these magazines that I was trying to get into that were rejecting me, and I didn’t even want to read them. And at a certain point, I was like, ‘There’s something wrong here.’”

So she began to write essays, and something clicked. Essay writing immediately struck her as a more appropriate form for exploring the ideas that excited her, and after years of rejected short stories, as an essayist she found quick success.

Her first published essay, which appeared on a website called The Awl, was about a group of girls with online crushes on the Columbine killers. “I sort of related to these girls in the ferocity of their crushes,” she recalls. “Female rage is something that’s not really permitted, and so instead of being like, ‘Oh my god, I’m bullied, I’m miserable, I’m so unhappy,’ instead of owning that feeling, which is not socially permissible, then you idolize this boy who acted on it.”

Being published was good. Caring about what she wrote was great. Doing research was fun. And she no longer felt like she was faking it. Suddenly, she was off and running on a new, entirely unexpected career in nonfiction.

After completing her MFA, she stayed on in Baltimore for a couple of years, writing for a website run by fellow Sagehen Susan Dunn ’84, called Baltimore Fishbowl. And then, she simply knew it was time to move on.

“I’ve made most of my decisions in life kind of intuitively,” she explains, “so they’re hard to explain after the fact. But I had a sense that, ‘OK, I’ve plateaued here. I’ve reached some sort of limit. Time to go.’”

So she packed up her car and drove west.

* * *

ACCORDING TO THE Texas State Historical Association, the town of Marfa was founded in 1883 as a water stop and freight depot for the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway. The rail line slices straight through the heart of town, and a couple of times a day, seemingly endless freight trains come barreling through. The landscape here is flat and barren, covered with sparse grasses and low vegetation like creosote and yuccas, so you can literally see the train coming for miles. But the trains don’t stop here anymore, and their only apparent contribution to the local economy is a negative one—the cost of earplugs provided to guests in a nearby hotel.

Back in the 1940s, the town’s population topped out at about 5,000, bolstered by a prisoner-of-war camp and a military base. When those vanished after war’s end, Marfa seemed destined to slowly fade away, like so much of small-town America. But in recent years, the town’s population has stabilized at around 2,000, thanks to the two rather discordant pillars of its modern economy—arts tourism and the Border Patrol.

* * *

MONROE DOESN’T REMEMBER much about her first impression of Marfa, but she remembers the high desert landscape surrounding it. Somewhere around the town of Alpine, the scene began to shift. “All of a sudden, it just looked kind of rugged and open and empty,” she says, “and I got really excited about the way it looked. I was like, ‘Oh, I’m in the West.’”

In Marfa, exhausted from her eight-hour drive from Austin, she crashed at El Cosmico, a quirky hotel-slash-campground where visitors sleep in trailers, teepees and tents. The next day she took a tour with the Chinati Foundation, one of two nonprofits—the other being the Judd Foundation—that promote the arts in and around Marfa.

Then she drove on. But she couldn’t quite leave Marfa behind.

“When I got to L.A., I was like, ‘You know, if I moved here, I would have to get a job because it’s just expensive. And I don’t want a real job.’ Then I had this plan to drive back through Montana and Wyoming, but for some reason I kept thinking, ‘That Marfa place was real interesting.’”

Since she hadn’t been able to write much on the road (“It’s hard when you’re sleeping on friends’ couches”), she decided to return to Marfa and find a place to settle in for a week or so and write.

What drew her back to Marfa? It’s another of those intuitive decisions that she has trouble explaining. “I’m not sure I could have said at the time. I can make something up now, but I was just like, ‘Oh, that’s a cool place. It’s real pretty. It seems easy to find your way.’ It just seemed like the kind of place where you could go and be for a week and get some writing done.”

That week stretched into six. “And at the end of that, I was like, ‘I think I’m just going to move here.”

* * *

THE BORDER PATROL has been an integral part of life in Marfa since 1924, when it was created by an act of Congress—not to control immigration, but to deter the smuggling of liquor across the Rio Grande during Prohibition. That mission soon changed, however, and today, the Patrol’s Big Bend Sector—known until 2011 as the Marfa Sector—is responsible for immigration enforcement for 77 counties in Texas and 18 in Oklahoma.

Headquarters for the whole sector is just south of town, near El Cosmico, and uniformed Border Patrol agents are a conspicuous presence in Marfa’s coffee shops and on its streets. According to the sector’s website, it now employs about 700 agents and 50 support staff. Among them, Monroe says, are quite a few young men and women who grew up right here in town.

Headquarters for the whole sector is just south of town, near El Cosmico, and uniformed Border Patrol agents are a conspicuous presence in Marfa’s coffee shops and on its streets. According to the sector’s website, it now employs about 700 agents and 50 support staff. Among them, Monroe says, are quite a few young men and women who grew up right here in town.

The other pillar of Marfa’s economy doesn’t jump out at you until you walk up Highland Street toward the big pink palace that houses the Presidio County Courthouse. Glance inside the aging storefronts, and where you might expect to find a Western Auto or a feed store, you’ll find, instead, art gallery after art gallery.

The story of Marfa as a destination for art lovers begins in the early 1970s with the arrival of minimalist artist Donald Judd. Drawn to Marfa by its arid landscapes, he soon began buying up land, first the 60,000-acre Ayala de Chinati Ranch, then an entire abandoned military base. In what must have seemed a grandly quixotic gesture at the time, he opened Marfa’s first art gallery.

Then something strange and wonderful happened. Artists began to gravitate to this dry little West Texas town to be part of a growing arts scene, and behind them, in seasonal droves, came the arts tourists.

* * *

MONROE’S WRITING CAREER really took off after she moved to Marfa—a fact that she believes is no coincidence. “It wasn’t my intention in moving out here, but I think living here has been an advantage in that I come across a lot of stories,” she says. “Things kind of bubble up here—not just regional stories either.”

Some of those stories, which increasingly have appeared in prominent national venues like The New Yorker, New York Magazine, Slate, The New Republic, and The Guardian, have grown directly out of her engagement in the Marfa community. In fact, the article that really put her on the map for national editors happened, in large part, because of her decision to join the local fire department.

“I read Norman Maclean’s book Young Men and Fire,” she says. “I just loved that book, and then I was like, ‘Oh wait, I’m moving to a place where they have wildfires.’” Fighting fires, she thought, would be a good way to connect with the land, and as a writer, she was drawn by the sheer drama of firefighting. “And then, you learn so much about the town,” she adds. “You know—not just the tourist surface, but the rural realities of living in a place.”

A year later, when a fertilizer plant exploded in West, Texas (“That’s West—comma—Texas, which is actually hours east of here”), Monroe found that her status as a first responder was her “in” for an important story. In the course of the investigation, a firefighter named Bryce Reed had gone from local hero to jailed suspect. Monroe wanted to tell his story, and her credentials as a fellow firefighter were key to earning his trust.

The resulting article, which she considers her first real work of in-depth reporting, became a study of Reed’s firefighter psyche and the role it played in his ordeal and his eventual vindication. “In my experience, it’s not universal, but a lot of people who are willing to run toward the disaster, there’s some ego there,” she says. “And it seemed to me that in some ways he was being punished for letting that ego show.”

The 8,000-word piece, which appeared in Oxford American in 2014, helped shift her career into high gear. Despite her usual writer’s insecurities about making such a claim herself (“As soon as you say that, a thunderbolt comes and zaps you”), she hasn’t looked back.

Recently, she put her freelance career on hold in order to finish a book, the subject of which harkens back to her very first published essay—women and crime. “It centers on the stories of four different women over the course of 100 years, each of whom became obsessed with a true crime story,” she says. “And each of those four women imagined themselves into a different role in the story. One becomes the detective, one imagines herself in the role of the victim, one is the lawyer, and one is the killer.”

She already has a publisher, along with a deadline of September to finish the draft. What comes after that, she doesn’t even want to think about. “For now, I’m just working on this book,” she says, “and the book feels like a wall I can’t see over.”

* * *

THAT DESCRIPTION—a wall I can’t see over—might also apply to how I feel about Marfa as I walk up its dusty main street. From a distance, today’s Marfa seems to be a strange composite—a place where down-home, red-state America and elitist, blue-state America meet cute and coexist in a kind of harmonious interdependence.

As I walk, I see things that seem to feed that theory—like two men walking into the post office, one dressed all in black, with a shaved head and a small earring, the other in a huge cowboy hat and blue jeans, with a big bushy mustache and a pistol on his hip.

But at the same time, I’m struck by the sense that there are two Marfas here, one layered imperfectly over the top of the other, like that old sky-blue Ford F250 pickup I see parked in the shade of a live oak, with a surreal, airbrushed depiction of giant bees stuck in pink globs of bubblegum flowing down its side.

Monroe quickly pulls me back to earth—where the real Marfa resides.

* * *

“THIS IS NOT a typical small town,” she says, “There’s not a ton of meth. There are jobs. It’s easy to romanticize this place, but it’s an economy that is running on art money and Border Patrol money, and I don’t know if that’s a sustainable model. You can’t scale that model.”

Monroe is quick to point out that the advantages conferred by Marfa’s unique niche in the art world are part of what makes the little town so livable. That’s why she’s able to shop at a gourmet grocery store, attend a film festival and listen to a cool public radio station. “You know, I don’t think I could live in just, like, a random tiny Texas town,” she admits.

But those things are only part of what has kept her here. The rest has to do with the very real attractions of small-town life—or rather, of life in that dying civic breed, the thriving small town. “This is the only small town I’ve ever lived in,” she says, “and it’s such a unique case. It does have, in its own way, a booming economy, right? And I think that’s not the case for a lot of small towns, where you get a lot of despair and disinvestment and detachment, because there’s not a lot of hope that anything can change or get better. People like coming here, people like living here, because it largely feels good, because it has found this economic niche, so that it’s not a dying small town. And that’s rare, and I think there’s a hunger for that.”

As a volunteer in the schools, the radio station and—of course—the fire department, Monroe is engaged in the community in ways that seem to come naturally here. “Yeah, you can’t be like, ‘That’s not my area. That’s not my role.’ Everybody here is required to step up and help out, and that feels like the norm.”

She has also come to appreciate Marfa’s small-town emphasis on simply getting along. “I wouldn’t say my lesson here has been assuming good faith on the other side or something like that. It’s more diffuse than that—just the sense that when you live in this small place, there is a strong sense of mutual reliance, just one school, one post office, one bank that you share with people who are different from you. And you realize that other people’s opinions are more nuanced.”

Anyway, she says, residents are far more likely to be vociferous about local decisions than national ones—for example, a move to put in parking meters on Marfa’s streets. “People can get way more fired up about that than about stuff that feels somewhat removed from here.”

All in all, Marfa just feels like home in a way Monroe has never experienced before. “It’s a quiet, beautiful life, but not too quiet. I think there’s an element of small-town, mutual care. We’re in it together. That is really nice. I like that my friends include everybody from teenagers to people in their 70s—a much more diverse group, in every sense of the word, than when I was living in Baltimore.”

Ask whether she’s here to stay, however, and her reaction is an involuntary shudder. “Who are you—my dad?” she laughs. “I don’t know. I can’t—no comment. I really have no idea.”

After all, a person who follows her intuition has to keep her options open.

* * *

LEAVING MARFA, I stop for a few moments to take in one of its most iconic images—a famous art installation known as Prada Marfa. If you search for Marfa on Google, it’s the first image that comes up. And a strange scene it is—what appears to be a tiny boutique, with plate-glass windows opening onto a showroom of expensive and stylish shoes and purses, surrounded by nothing but miles and miles of empty scrub desert. Looking at it before I made the trip, I thought it was a wonderfully eccentric encapsulation of what Marfa seemed to stand for.

LEAVING MARFA, I stop for a few moments to take in one of its most iconic images—a famous art installation known as Prada Marfa. If you search for Marfa on Google, it’s the first image that comes up. And a strange scene it is—what appears to be a tiny boutique, with plate-glass windows opening onto a showroom of expensive and stylish shoes and purses, surrounded by nothing but miles and miles of empty scrub desert. Looking at it before I made the trip, I thought it was a wonderfully eccentric encapsulation of what Marfa seemed to stand for.

Here’s the irony—it’s not really located in Marfa at all. It’s about 40 miles away, outside a little town called Valentine. But I suppose “Prada Valentine” just wouldn’t have the same ring.

What makes a poem appealing? People prefer poetry that paints a vivid picture, according to a new study from a trio of researchers, including Pomona College President G. Gabrielle Starr, a scholar of English literature and neuroscience.

What makes a poem appealing? People prefer poetry that paints a vivid picture, according to a new study from a trio of researchers, including Pomona College President G. Gabrielle Starr, a scholar of English literature and neuroscience.

It was also at Pomona that Monroe started to get serious about writing. Looking back, she credits the late Disney Professor of Creative Writing, David Foster Wallace, with helping her to grow from a lazy writer into a hardworking one. “He would mark up stories in multiple different colors of pen, you know, read it three or four times, and type up these letters to us,” she explains. “You really just felt like you were giving him short shrift and yourself short shrift if you turned in something that was kind of half-assed.”

It was also at Pomona that Monroe started to get serious about writing. Looking back, she credits the late Disney Professor of Creative Writing, David Foster Wallace, with helping her to grow from a lazy writer into a hardworking one. “He would mark up stories in multiple different colors of pen, you know, read it three or four times, and type up these letters to us,” she explains. “You really just felt like you were giving him short shrift and yourself short shrift if you turned in something that was kind of half-assed.” Headquarters for the whole sector is just south of town, near El Cosmico, and uniformed Border Patrol agents are a conspicuous presence in Marfa’s coffee shops and on its streets. According to the sector’s website, it now employs about 700 agents and 50 support staff. Among them, Monroe says, are quite a few young men and women who grew up right here in town.

Headquarters for the whole sector is just south of town, near El Cosmico, and uniformed Border Patrol agents are a conspicuous presence in Marfa’s coffee shops and on its streets. According to the sector’s website, it now employs about 700 agents and 50 support staff. Among them, Monroe says, are quite a few young men and women who grew up right here in town. LEAVING MARFA, I stop for a few moments to take in one of its most iconic images—a famous art installation known as Prada Marfa. If you search for Marfa on Google, it’s the first image that comes up. And a strange scene it is—what appears to be a tiny boutique, with plate-glass windows opening onto a showroom of expensive and stylish shoes and purses, surrounded by nothing but miles and miles of empty scrub desert. Looking at it before I made the trip, I thought it was a wonderfully eccentric encapsulation of what Marfa seemed to stand for.

LEAVING MARFA, I stop for a few moments to take in one of its most iconic images—a famous art installation known as Prada Marfa. If you search for Marfa on Google, it’s the first image that comes up. And a strange scene it is—what appears to be a tiny boutique, with plate-glass windows opening onto a showroom of expensive and stylish shoes and purses, surrounded by nothing but miles and miles of empty scrub desert. Looking at it before I made the trip, I thought it was a wonderfully eccentric encapsulation of what Marfa seemed to stand for.

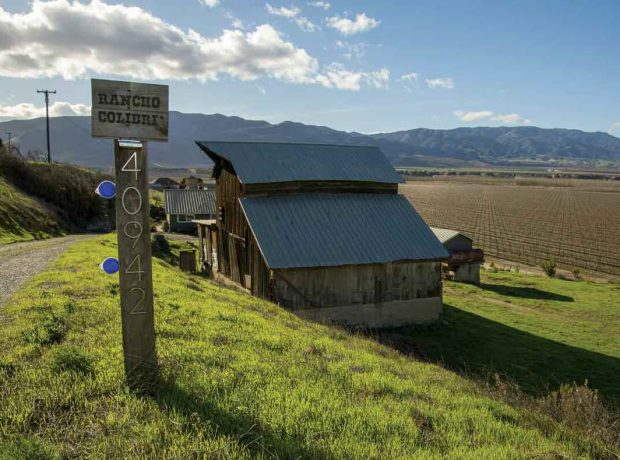

“She used to have this little hand pump and walk around the farm, so I got this big pump that hooks up to the battery of this Kawasaki Mule,” says Chris, who explains he drives the small vehicle with Jazmin hunched next to him spraying the weeds. “The neighbors think we’re crazy because I’ll be driving as slow as possible and she’ll be hitting these little things at the base. The neighbors ask why we don’t just boom spray and kill it all and then bring back only what we want, but Jazmin is very passionate about the local flora and fauna.”

“She used to have this little hand pump and walk around the farm, so I got this big pump that hooks up to the battery of this Kawasaki Mule,” says Chris, who explains he drives the small vehicle with Jazmin hunched next to him spraying the weeds. “The neighbors think we’re crazy because I’ll be driving as slow as possible and she’ll be hitting these little things at the base. The neighbors ask why we don’t just boom spray and kill it all and then bring back only what we want, but Jazmin is very passionate about the local flora and fauna.”

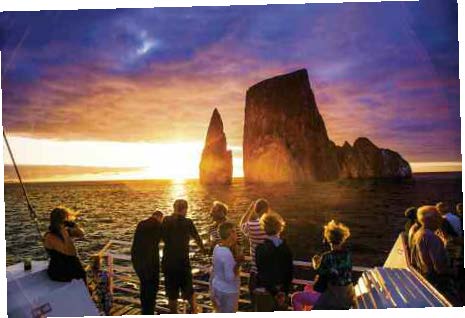

This spring, the Pomona College Book Club will discuss The Lost City of the Monkey God: A True Story by Douglas Preston ’78. Named a New York Times Notable Book of 2017, the story follows Preston’s rugged expedition in search of pre-Columbian ruins in the Honduran rain forest. Join the

This spring, the Pomona College Book Club will discuss The Lost City of the Monkey God: A True Story by Douglas Preston ’78. Named a New York Times Notable Book of 2017, the story follows Preston’s rugged expedition in search of pre-Columbian ruins in the Honduran rain forest. Join the

Alumni Weekend 2018

Alumni Weekend 2018 Pomona in the City: Seattle

Pomona in the City: Seattle

Permission to Die

Permission to Die Spiritual Citizenship

Spiritual Citizenship My Pomona College

My Pomona College Indecorous Thinking

Indecorous Thinking Bones Around My Neck

Bones Around My Neck A Second Course in Linear Algebra

A Second Course in Linear Algebra Where There’s Smoke

Where There’s Smoke The Party’s Primary

The Party’s Primary The Ballad of Huck & Miguel

The Ballad of Huck & Miguel