Eclipse Memories

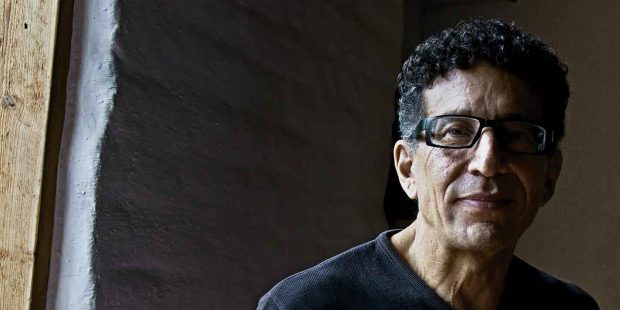

Close-up of the total eclipse. Photo by Tom and Judith Auchter, digitally enhanced by Lew Phelps ’65

Thanks to Chuck and Lew Phelps (both ’65) for the interesting article about the Pomona eclipse event in Wyoming in August. The opportunity to share the experience with Pomona friends and family was stunning, and the article captured the depth of the adventure. It is amazing that they had the foresight to plan two years in advance and to reserve one of the premier spots in the U.S. to view the spectacle. The twins worked tirelessly on every aspect of our time together, including housing, meals, a lecture series and guided stargazing, and they created a deeply memorable experience for everyone on the mountain.

Wishing to honor the Phelpses, attendees from the Class of ’65, as well as the Classes of ’64 and ’66, created a Pomona fund to celebrate our time together. At the final group lunch, we announced the Phelps Twins Eclipse Fund to support Pomona summer internships in science. The response was heartening: 86 donations came from Pomona alumni and friends who attended the event and from some who did not but who wanted to support the fund. The final figure was $52,242. The fund will support more than 10 summer internships for students in future years.

With appreciation to Chuck and Lew for making it happen.

—Ann Dunkle Thompson ’65, P’92

—Celia Williams Baron ’65

—Virginia Corlette Pollard ’65, P’93

—Jan Williams Hazlett ’65

—Peter Briggs ’64, P’93

Excelling Wisely

When I received the Fall 2017 edition of PCM, I was intrigued by the front cover’s puzzle shapes, where work and life fit together. As a creative writing and reading intervention teacher at STEM Prep High School in Nashville, TN, I wrestle with this question of how to fit life and work together without work consuming both pieces. I was absolutely delighted, upon opening to the article “Excelling Wisely,” to read these lines by the president of Pomona College: “We need to tell ourselves and each other that we can achieve and excel without taking every drop of energy from our reserves. That we all need to take some time to laugh.” And later President Starr adds, “Creativity requires freedom, space and room to grow. And achievement isn’t the only thing that adds meaning to our lives.”

This article hit home to me as I was struggling with just one more bout of sickness after a challenging but fulfilling semester of teaching. Its message needs to be heard in every corner of our world. Yes, achievement is important. But the quality of our lives as we accomplish our goals is also important. In my work environment at STEM Prep Academy, I am surrounded by motivated, hardworking, yet caring leaders who themselves are asking these questions. Students today are extremely stressed. Many of our students face particular language challenges, which further contributes to stress. How can we help to close the achievement gap and yet not become consumed by it?

STEM Prep High is intentionally trying to create balance this year by adding once-a-month Friday afternoon clubs. These clubs enable students to explore interests and to spend more relaxed time in a group of their choosing. I lead a sewing and knitting club, which has attracted a very “chill” group of students. I provide knitting needles, crochet hooks, yarn and other items, assisting as students explore these crafts. Other clubs include flag football, hiking, a Socrates club, games and yoga.

STEM Prep High has also created balance this year by offering elective classes such as Visual Arts and Imaginative Writing. My Imaginative Writing classroom is intentionally filled with creativity and fun, including a bookshelf full of children’s stories, teen books and adult novels. A stuffed Cat in the Hat and a Cheshire Cat lounge on top of the bookshelves. Plants adorn the top of the filing cabinet near the window, creating a homey, relaxed atmosphere. During the month of November my students and I participated in NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month). This provided students with an opportunity to creatively express their own life stories or stories that they had made up.

And what about teachers? How can we create a tenuous balance between work and life? Certainly, our work is important, but so are our lives. I continue to wrestle with this question. One “solution” that my husband created was buying season tickets to the Nashville Predators games. This allows my husband and me to enjoy downtown Nashville and to spend time together. We also enjoy motorcycle trips on my husband’s Harley.

Most of us will continue to face this challenge of how to “excel wisely” throughout our lives. I was most grateful for this issue of PCM and the opportunity to reflect on ways in which I am trying to make this happen and ways in which I can continue to create a healthy balance between work and life.

—Wilma (Fisher) Lefler ‘90

Wow!

Wow! The recent issue of PCM is superb. Each story is meaty and unique and engaging. I’m one who usually reads an issue from cover to cover, and this one left me wanting to start at the beginning again with the suspicion that I’d surely missed important details along the way.

Thank you for the imagination, creativity and careful editing that you give in helping us feel connected and proud.

PS: I’m one of the trio who were the first exchange students from Swarthmore in spring 1962 at the invitation of Pomona. It pleases me that both colleges are currently led by African-American women.

—Betsy Crofts ‘63

Southampton, PA

Alumni, parents and friends are invited to email letters to pcm@pomona.edu or “snail-mail” them to Pomona College Magazine, 550 North College Ave., Claremont, CA 91711. Letters may be edited for length, style and clarity.

During your first semester at Pomona, take a Linear Algebra course with Professor Stephan Garcia, whose problem-solving approach to teaching impresses you so much that you can’t wait to take another course with him second semester.

During your first semester at Pomona, take a Linear Algebra course with Professor Stephan Garcia, whose problem-solving approach to teaching impresses you so much that you can’t wait to take another course with him second semester.