Yet, as the library slouched toward insolvency, Lantz was surprised by the silence. No citizens storming the council chambers. No emails or phone calls. Not even a tap on the councilwoman’s shoulder from a fellow library lover in line at the grocery store.

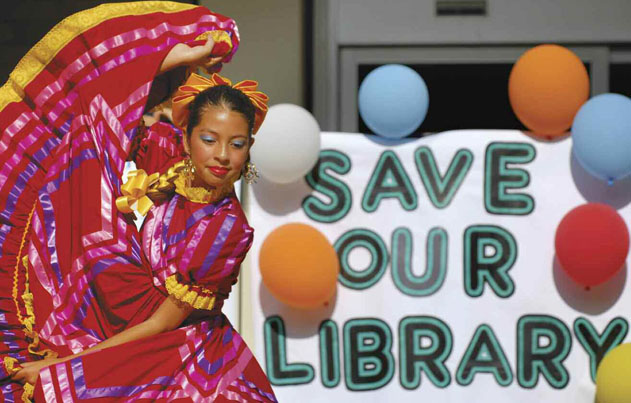

It wasn’t until earlier this year, when the city announced that it would be forced to close the library for a full year, that supporters came forward in strength. They held rallies on the library steps, protested at council meetings, organized fundraisers and revived a dormant foundation for raising private funds to help keep the library afloat. That burst of activism, says Lantz, is the only silver lining in a budget crisis that threatened to give Pomona, the College’s birthplace and namesake city, the distinction of becoming one the largest municipalities in the country without a public library.

Under public pressure, the city found funds to keep the library open another year, albeit on a skeleton staff and a miserly annual budget of $400,000, less than 15 percent of its peak funding in 2007. The city council has also approved a ballot measure calling for a library tax of $38 per year on all Pomona properties. The tax, which requires two-thirds approval in November, is considered a long shot, but it may be the library’s only shot considering the city’s dismal long-term fiscal forecast.

Next year, without a new source of funds or a miracle, the library may be broke again. For now, the protesters succeeded in delaying the doomsday decision.

“It makes it a whole lot easier to make cuts if it’s just numbers on a page, rather than looking into people’s eyes,” says Lantz, who launched a community task force to save the library. “It took the drastic measure of closing the library to get everyone’s attention. But I wish it had happened four years ago.”

POMONA HAS PLENTY OF COMPANY in its biblio-budget battles. For more than a decade, libraries across the country, including the Library of Congress, have been forced to tighten their belts and cut back on service. And, as it turns out, the public’s reaction to the Pomona library’s plight—chronic unconcern before last-minute mobilizations—is also part of the national trend.

Budget cuts have crippled libraries from New York to Newport Beach, Calif., where a plan last year called for replacing librarians with videophones for patrons to call in their reference questions. Three years ago, only state intervention averted a radical plan that would have closed all 54 branches of the Free Library of Philadelphia. The following year in Brooklyn, protestors staged a 24-hour read-in to stop the imminent closure of 40 library branches. Their slogan: “We will not be shushed.”

The library cutbacks are so widespread that the Huffington Post created a special section titled, “Libraries in Crisis.” Just perusing the headlines underscores the extent of the threat to these temples of knowledge:

–Children’s Laureate Warns ‘Society Will Pay’ For Library Closures

–Can a Protest Save a Library?

–After Branches Close, Students Set Up Outdoor Libraries

In his introduction to the series, HuffPo Books Editor Andrew Losowsky calls for a “national conversation” about the evolving nature and future of libraries. “If information is power,” he writes, “then libraries are the essence of democracy and freedom.”

NOBODY KNOWS THE budget ups and downs of the Pomona Public Library better than Greg Shapton ’71, the former director who retired last year after almost half a century as a library employee. Shapton started there as a part-time page, working with the library’s collection of 16-mm movies. It was 1967, the same year he enrolled as a freshman at Pomona College. Though he graduated with a degree in psychology, his major for a while was math. That training would come in handy as an administrator, juggling budgets and allocating ever-diminishing resources.

NOBODY KNOWS THE budget ups and downs of the Pomona Public Library better than Greg Shapton ’71, the former director who retired last year after almost half a century as a library employee. Shapton started there as a part-time page, working with the library’s collection of 16-mm movies. It was 1967, the same year he enrolled as a freshman at Pomona College. Though he graduated with a degree in psychology, his major for a while was math. That training would come in handy as an administrator, juggling budgets and allocating ever-diminishing resources.

Now 63, Shapton looks back at his first decade as a golden era for the library, a modern architectural centerpiece of the civic center on Garey Avenue. But with the passage 34 years ago of Proposition 13, the state’s sweeping anti-tax measure, “the library was really gutted,” says Shapton, who was head of the reference desk at the time. “That began the downward slide, not just for the Pomona Library but for cities in general.”

In the immediate aftermath of the 1978 tax revolt, the library lost half its budget and half its staff, recalls Shapton. Exactly 30 years later, the library would be buffeted by yet another historic force, this time the worldwide financial collapse of 2008. Since then, the city’s general fund budget—which pays for essential services such as police and fire protection, as well as the library—has plunged by $20 million, or 22 percent of its high of almost $90 million. Pomona went from budget surpluses to annual deficits.

In fiscal 2007-08, the library budget had peaked at just over $3 million with 56 hours of operation. Three years later when Shapton finally retired, it was down to a tight but survivable $1.6 million and 26 hours.

Just when it seemed things couldn’t get any worse, they did. The budget was trimmed even further in the current fiscal year, down to $1.1 million and 20 positions. Then, the real calamity struck. Suddenly, there was a gaping new hole in the city’s operating fund.

This year, the city faced an unanticipated shortfall, due in part to the loss of $1.1 million in tax revenue tied up in a messy, drawn-out legal battle. The funds vanished in May as a result of a surprise appellate court ruling in a case involving the state Board of Equalization and several Southern California cities. The city was caught flat-footed when the court shot down a deal that cities had hammered out over how to share the disputed tax revenue.

In its scramble to make up for the loss, the city almost immediately announced it would be forced to close the library for a full year and lay off the entire library staff. In their defense, city administrators argue that Pomona has been hit disproportionately by hard times, leaving them with only painful options for cutting the budget. The city’s tax base, already weak in comparison to some wealthier neighbors, was crippled in recent years by the flight of major retailers. Car dealerships shut down. Big-box stores like Toys “R” Us left town. The result: Pomona’s sales tax per capita was $87 in fiscal 2010-11, compared to $316 for the nearby city of Ontario.

The paradox in this municipal numbers game is that the deeper the economic crisis, the more people need their free library. That is especially true, supporters say, in a poor, predominantly Latino city like Pomona where people may not have Internet access at home and rely on the library for school research, job searches and even adult literacy lessons.

“It’s tragic,” says Religious Studies Professor Erin Runions, who has lived in Pomona for four years. “The cities are being cut by the state, the state is being cut by the federal government. And who ends up paying for that? It’s people who can’t afford to buy books or computers. People who rely on the library as a source of education, a source of information, as a source of transformation. Those are the people who lose out.”

POMONA’S FIRST LIBRARY was founded in 1887, the year before the city itself was incorporated, by a small group of women who were members of a garden club. By 1890, the city officially took over library operations, promising under contract to keep it in good condition and add new books every year. Soon, the library was seeking a permanent building and turned to philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who saw free public libraries as essential to the development of communities and supported their construction throughout the country.

In a letter to Carnegie dated Dec. 3, 1901, a Pomona library board member made a pitch for funds. His letter included an appeal on behalf of students attending a fledgling college that had been established in the city the very same year as the library. “Pomona College, a young but growing institution of some 300 students, relies largely on the facilities offered by the Pomona Public Library,” the trustee wrote, “and greatly needs more assistance than we can now afford with the resources at our command.”

By then, the College had already moved to its new location in Claremont, which at first was considered temporary. But the letter to Carnegie underscores how closely intertwined were these two institutions at the start.

To mark its own 125th anniversary, Pomona College has established a theme of “community,” pledging to connect the campus with its neighbors, including the city of its birth. A handful of faculty members and students are looking for ways to put that theme into action by connecting with the Pomona Library in its time of need. They have met informally to discuss the issue, explored ways for the College to get involved, posted appeals for action on their Facebook pages and privately alerted college officials of their concern.

“We’ve been talking a lot recently about our interactions with the local community,” says History Professor April J. Mayes ’94. “To me, this is a perfect opportunity to bring Pomona College back into Pomona again.”

Mayes feels so strongly about the issue because, like many supporters, her whole life has been memorably intertwined with the library. As a child she spent hours in the Laura Ingalls Wilder Children’s Room, fascinated by the collection of memorabilia from the author of Little House on the Prairie. Later, while attending Pomona Catholic Girls High School, Mayes worked as a library page. And finally, while researching her senior thesis on local history at Pomona College, Mayes returned to her hometown library to make use of its special collections, consulting newspaper microfiche and first edition books written in the late 19th century.

“The special collections is pretty amazing,” she says. “It’s a pretty extensive gathering of great materials on the history of, not just the city of Pomona, but the entire region.” Professor Runions, the biblical scholar, moved to Pomona four years ago, looking for more diversity than Claremont had to offer. This summer, Runions got involved in the library task force and joined the opposition in another messy issue, the battle over a proposed new trash transfer facility she considers an example of “environmental racism.” She also is helping to campaign for passage of the library parcel tax.

As a transplant from British Columbia in 2005, Runions felt “somewhat like an outsider trying to make a home here.” She settled on Pomona and has not regretted it.

“We love it here,” says Runions, who lives in the city’s historic Lincoln Park area. “There’s a real sense of community in Pomona, and I think that’s what the library task force really shows, that there are citizens who are concerned about the well-being of this city. Deeply concerned. They’ve been here many years and they’re really willing to put in the time and the work. But they need some leadership.”

POLITICAL LEADERSHIP is precisely what’s lacking in Pomona, says Gwen Robinson ’60, head of Friends of Pomona Public Library, a volunteer group founded in 1955. Robinson, a retired school teacher, assails city leaders for consistently short-changing the library in favor of other city services. She fears if the tax plan doesn’t pass, the library will shut down for sure next year, and she blames the city council for letting it happen. “They don’t have a plan and they don’t want to look for any other cuts,” said Robinson, who attended Pomona College for two years as an undergraduate. “They just don’t want to deal with it any more.”

Robinson and other library supporters bristle at the suggestion that civic apathy permitted the library to become an easy target for the budget axe. Yet, a study by Public Agenda, a public opinion firm in New York, found a pattern of what it calls “benign neglect” has undermined libraries nationwide. Libraries enjoy broad public support, the 2006 study found, but even the most ardent library lovers are not aware of budget problems until there is a full-blown crisis. And cities don’t act until the public mobilizes.

Civic leaders surveyed echoed Councilwoman Lantz’ concerns about the public’s “impassive advocacy” in the face of repeated library cutbacks. But she adds that what appears to be apathy may be a matter of generational values instead.

Lantz, who majored in sociology and earned a master’s in education from Claremont Graduate School, uses her own four adult children as examples. They all have moved away, settling in cities from Nashville, Tenn., to Oakland, Calif. But they have one thing in common. Their 30-something generation has grown detached from civic life at a local level, even as they engage on a global level with communities on the web. They can’t name their mayor, don’t read a local paper, don’t know about redevelopment and, she adds, “they don’t care.”

Things were different in her day, says Lantz, now 66. She was born in Pomona, like her dad before her. His was a generation that put down roots in one place for a lifetime. Her mother, who’s 97, still lives in the home the family built when Lantz was attending Pomona High School. Her folks didn’t have money to buy books, so they took her as a child to the library, then in the old Carnegie building. That turn-of-the-century structure was torn down for a bank parking lot and replaced in 1965 by the current building. But no matter where the books are housed, Lantz’ mother still visits the library to this day.

Lantz is encouraged to see young people join the library task force. And she concedes the city shares the blame for failing to find a way to reach them, until it was almost too late.

“We don’t communicate with them in the way they communicate,” Lantz says.

LIKE LANTZ, Carla Maria Guerrero ’06 was also born and raised in Pomona. She hasn’t volunteered on the task force, but she’s following the library issue on Facebook. She says the threatened closure has “galvanized” library supporters on the Internet.

“It’s a little unfair to say the newer generations don’t care,” asserts Guerrero, 28. “In activist circles online, I would dare say people are upset. Many people might not be able to come out (for meetings), but we’re all still avidly following it.”

Guerrero is the daughter of immigrants who came from Mexico with limited schooling. But they always stressed education. Her father, Homero Guerrero, was a factory worker who, on his time off, was “always on the hunt for good Spanish books.” He built a respectable collection by scooping up the tomes discarded by libraries from Los Angeles to Riverside.

Even after earning her bachelors degree in Latin American studies and her masters in print journalism from USC, Carla still lived in Pomona, sharing the family home with her parents and her two younger sisters. She also still used her hometown library, but now to check out audio books for her three-hour daily commute to Los Angeles where she works. That’s how she discovered the library hours had been cut back. Then, after moving to L.A. last year, she found out about the planned shutdown from her sister, who saw it posted on Facebook.

“If the closure ever happens, it would be really sad,” she says. “The library is one of the few public institutions that stands for knowledge, not for profit. It’s something so pure, it’s actually there for the good of the people. It’s something that a city like Pomona, that is already pretty impoverished, cannot afford to lose.”

Update: The library parcel tax, Measure X, failed in the Nov. 6 election, receiving just over 60 percent approval, short of the two-thirds required.

Susanne wanted those things, too. At Pomona, she embraced the life of the mind, engaging in those deep late-night conversations, and finding “just the right mix of serious study and social life.” She was an English major—Phi Beta Kappa and Mortar Board—who had many friends in the sciences. She served as arts and culture editor for The Student Life, and also took modern dance classes from Professor Jeannette Hypes, performing several times in her dance troupe. She soaked up everything she could from the small liberal arts college atmosphere.

Susanne wanted those things, too. At Pomona, she embraced the life of the mind, engaging in those deep late-night conversations, and finding “just the right mix of serious study and social life.” She was an English major—Phi Beta Kappa and Mortar Board—who had many friends in the sciences. She served as arts and culture editor for The Student Life, and also took modern dance classes from Professor Jeannette Hypes, performing several times in her dance troupe. She soaked up everything she could from the small liberal arts college atmosphere. Maintenance Shop Supervisor Orlando Gonzalez is a hands-on kind of guy, working alongside his five-person crew on everything from unclogging shower drains to replacing shingles. But it’s his mind and his memory that are key to keeping the campus in tip-top shape.

Maintenance Shop Supervisor Orlando Gonzalez is a hands-on kind of guy, working alongside his five-person crew on everything from unclogging shower drains to replacing shingles. But it’s his mind and his memory that are key to keeping the campus in tip-top shape.

Williams: I want to talk about Berg’s policy arguments, which are controversial. He says we should consolidate all federal food programs into one efficient entity, have a universal school breakfast, reward states to reduce hunger; allow nonprofits to compete for federal funds; give recipients more choice, provide additional services such as job training. What do you think?

Williams: I want to talk about Berg’s policy arguments, which are controversial. He says we should consolidate all federal food programs into one efficient entity, have a universal school breakfast, reward states to reduce hunger; allow nonprofits to compete for federal funds; give recipients more choice, provide additional services such as job training. What do you think? FROM HOBBY TO COLLEGE MAJOR

FROM HOBBY TO COLLEGE MAJOR Under the night sky, local Native American tribes led an evening of drumming, singing, chanting and ritual dances in early September to mark the beginning of Pomona’s 125th anniversary. Held the same day students gathered in the morning for Convocation, the Native American ceremony brought to campus individuals whose ancestors inhabited this site long before the College was founded.

Under the night sky, local Native American tribes led an evening of drumming, singing, chanting and ritual dances in early September to mark the beginning of Pomona’s 125th anniversary. Held the same day students gathered in the morning for Convocation, the Native American ceremony brought to campus individuals whose ancestors inhabited this site long before the College was founded. Gifts of $500,000 from the Ahmanson Foundation, $500,000 from Trustee Bernard Chan ’88 and $100,000 from the Hearst Foundations will be used toward construction of the center, which is scheduled to be completed in spring 2014 at an estimated cost of $29 million. The planning and design of the building was made possible by an earlier gift from the estate of Pamela Creighton ’79. The College is seeking a naming gift for the center, as well as funding for additional spaces and other support.

Gifts of $500,000 from the Ahmanson Foundation, $500,000 from Trustee Bernard Chan ’88 and $100,000 from the Hearst Foundations will be used toward construction of the center, which is scheduled to be completed in spring 2014 at an estimated cost of $29 million. The planning and design of the building was made possible by an earlier gift from the estate of Pamela Creighton ’79. The College is seeking a naming gift for the center, as well as funding for additional spaces and other support.

For the past several years, veteran Pomona City Councilwoman Paula Lantz ’67 has found herself acquiescing to constant cutbacks to her hometown library, where she had spent so much of her youth. As city coffers shrank, library budgets were sliced, hours were slashed, staffing and special programs were squeezed.

For the past several years, veteran Pomona City Councilwoman Paula Lantz ’67 has found herself acquiescing to constant cutbacks to her hometown library, where she had spent so much of her youth. As city coffers shrank, library budgets were sliced, hours were slashed, staffing and special programs were squeezed. NOBODY KNOWS THE budget ups and downs of the Pomona Public Library better than Greg Shapton ’71, the former director who retired last year after almost half a century as a library employee. Shapton started there as a part-time page, working with the library’s collection of 16-mm movies. It was 1967, the same year he enrolled as a freshman at Pomona College. Though he graduated with a degree in psychology, his major for a while was math. That training would come in handy as an administrator, juggling budgets and allocating ever-diminishing resources.

NOBODY KNOWS THE budget ups and downs of the Pomona Public Library better than Greg Shapton ’71, the former director who retired last year after almost half a century as a library employee. Shapton started there as a part-time page, working with the library’s collection of 16-mm movies. It was 1967, the same year he enrolled as a freshman at Pomona College. Though he graduated with a degree in psychology, his major for a while was math. That training would come in handy as an administrator, juggling budgets and allocating ever-diminishing resources.