Veteran arts teacher Sal Perez ’75 roams around his high school ceramics studio like the benign boss of a buzzing Santa’s Workshop. He looks the part, with his stocky build, silvery hair pulled back in a ponytail, that cheerful round face and full-throated laugh. And Perez clearly loves guiding his artists in training, the students of Monrovia High School where for 23 years he has taught them to turn shapeless clay into objects of function and beauty.

Soon, a student calls him over to the electric wheel where she is struggling to give shape to her creation, which so far is a simple cylinder with straight sides.

“Let’s see,” says Perez, his strong hands permanently crusted with the white powdery coating of his trade. “What shape were you looking for?”

“I wanted it to go that way,” says the student, indicating a rounded vase with a small opening, “but it just kept going up.”

Perez dips his hands in water and leans over the clay, almost like an offensive guard at the scrimmage line, a position he played in his own high school days. He stands feet apart, leaning forward, his shoulders directly on top of the malleable material. As the wheel spins, he applies pressure and the clay suddenly turns wobbly and warped.

“He’ll fix it,” assures another student. “Calm down.”

By now, a group has gathered to watch Perez work. Their faces are a mixture of respect and astonishment. They smile and whisper to each other as their teacher turns the cylinder into a beautifully shaped vase with a rounded body and lipped opening, all within seconds.

Senior Tobi Scrugham can’t disguise her disbelief: “Wow, it took two periods to get as tall as it did, and he just takes one pass.”

Sal Perez is a rarity these days—a public school arts teacher with a flourishing classroom. In an era of severe funding cuts for the arts, Perez reigns over a roomy, well-equipped new studio on the high school campus in the San Gabriel Valley, halfway between Claremont and downtown L.A. With its rows of wheels, array of kilns and thriving enrollment, Monrovia High’s award-winning ceramics program would be the envy of any community college, and even some four-year institutions.

“For me, you can’t really have a good education unless you’re doing art,” he says. “Art is a way for students to be creative, and use the right side of the brain which also helps develop the left side.”

The son of Mexican-American field workers, Perez, 60, is an unlikely hero of arts education. Studies show that students from the socio-economic status of his youth are the least likely to be exposed to arts classes. As a child, his art instruction was grass roots. Perez’s father did sketches which he admired. And his cousin Ernie had a flair for painting cool flames on the sides of orange crates converted into go-karts. Perez didn’t discover his love of ceramics until he came to Pomona as the first in his family to go to college.

But his talent was evident from the start.

“Sal is by far the best student that I ever had, in terms of being a pure potter,” says Professor Emeritus Norm Hines ’61, his former arts teacher and mentor at Pomona. “Nobody came near him in terms of his ability as a ceramicist. To watch him on the wheel is like watching magic. But it’s not magic, it’s skill, acquired as a result of hard work and observation. And that’s what he transmits to his students. They don’t come out of his class thinking it’s magic. They come out thinking that they can do it, if they work hard and if they apply themselves. And I think that’s a really important thing to learn, especially for the kids he’s working with.”

AT MONROVIA HIGH, more than half the students are Latino, one of the groups hurt the most by cuts to arts classes. A 2011 report published by the National Endowment for the Arts showed that participation in childhood arts education has been on the decline since the early 1980s. Latinos have the lowest levels of arts training, 26 percent compared to 59 percent for their white peers, according to NEA’s 2008 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts.

AT MONROVIA HIGH, more than half the students are Latino, one of the groups hurt the most by cuts to arts classes. A 2011 report published by the National Endowment for the Arts showed that participation in childhood arts education has been on the decline since the early 1980s. Latinos have the lowest levels of arts training, 26 percent compared to 59 percent for their white peers, according to NEA’s 2008 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts.

“When a school takes away art, it’s really doing an injustice to the students because they’re not getting a complete education,” says Perez, who built his program by hook and by crook through grants, donations and plenty of his own resources. “It’s actually hurting the students, but somehow that’s what they believe they should take away.”

When it comes to providing long-term educational benefits, the arts do not discriminate. Longitudinal surveys have found an overall correlation between arts instruction and academic success. Low-income students with high arts participation have much lower drop-out rates and are twice as likely to graduate from college, compared to those with less arts involvement, according to another NEA report, “The Arts and Achievement in At-Risk Youth,” published last year.

Among the benefits, researchers note that “the arts reach students who might otherwise slip through the cracks.” That could well apply to 17-year-old senior Jonathan Bailey, who joined Monrovia High’s ceramics class last year. He was having family problems, with three separate moves to different homes. The imposing teenager was cutting class and getting into fights, his teacher recalled.

Ceramics turned out to be his therapy. The physical work shaping clay at the pottery wheel, a process known as throwing, relieved his stress. The creativity increased his confidence.

“Whenever I’m angry I seem to throw better because I take it out on the clay,” says Jonathan, who now wants to get his own wheel for his backyard. “I love hands-on work where I can build something and be proud. Ah, it’s the greatest feeling on the planet!”

Perez says he can relate to students because he’s seen his share of troubles too. Like trying to fit in at Pomona among more privileged white kids back in the early ’70s. Of the 35 Latinos accepted in his freshman class, he recalls, only 15 graduated. For Perez, the oldest of three brothers, the social pressure was heightened by being the family role model. He couldn’t fail because he had to set the example for those who would come after: “Hey, if Sal can do it, we can do it.”

“As a student at Pomona I was very alienated, because here I was living with people who were better economically off than I was, who had gone to private schools,” he recalls. “But I overcame that isolation through my work in ceramics. I would spend two or three days at a time in the studio, which was opened 24 hours a day. I had found a niche where I was comfortable. And as I got better in making the ceramic work, I found people started respecting that.”

SALVADOR RODRIGUEZ PÉREZ, as he is named on his college diplomas, was raised in one of the concrete homes built for Mexican workers by the San Dimas Packing House, a citrus farm company. There was no hiding the hostility of the time: As recounted in The Lie of the Land: Migrant Workers and the California Landscape, some believed the housing was too good for Mexicans. The farm’s manager argued it helped stabilize a workforce that arrived here “in a certain state of savagery or barbarism.” The goal of good housing was to encourage strong families, with the benefit of adding women and children to the labor pool. So it is not by chance that his mother, Clara, and father, Antonio, met at the packing house where they both worked.

As kids, Sal and his two younger brothers were always with their parents in the fields, which is where he learned the ethic of hard work. “I ate more oranges than I picked,” he jokes, “but we were never without any food. And I saw the sacrifices they made.”

Though his parents only had elementary schooling, they both stressed the importance of education. But being studious didn’t win him many friends in La Colonia, the barrio south of the tracks in San Dimas. “I was like the Latino nerd,” says Perez. “Everybody else was going to parties except me. My brothers would get invited, but they’d say, ‘Don’t invite Sal because he’s not one of us.’”

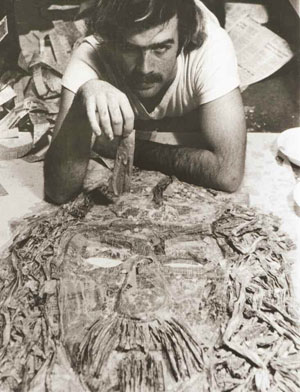

After graduating from Bonita High School, where he was co-captain of his football team, Perez attended Pomona, partly on scholarships, and ceramics quickly became his passion. His hours in the studio paid off, and before he turned 20, his ceramic work was already being featured in national exhibitions. He went on to get his MFA in 1977 from what was then The Claremont Graduate School. His goal was to teach at the college level, but when he failed to land a permanent appointment, he worked multiple jobs and saved money to open his own studio.

By the late ’70s, when rapid development devoured the old workers’ housing in La Colonia, Perez used his savings to buy his parents a new home in San Dimas, this time on the north side of the tracks. Tragically, his mother passed away just four months later and his father was left alone. So Perez, then 26, moved in with his father, and they lived together for the next three decades. When Perez got married, his wife Leticia also moved in, and they soon added a son, Seth, and daughter, Alana, to the extended family.

Perez was drafted into teaching, recruited in 1986 by middle school principal Linda Harding in Monrovia to teach ESL and bilingual classes. She offered an art class to sweeten the deal, and Perez accepted because he needed the money. His first year in the classroom was trial by fire, but four years later he was hired at the high school.

As his domestic responsibilities expanded, his dream of opening a studio faded. But he never stopped working, setting up a ceramics shop behind his house in a chicken coop with dirt floors, churning out pots for sale at festivals. Though it had been years since his student days, he still did his kiln work at Pomona, where Professor Hines kept the doors open for his former student, now his friend.

It’s a kindness Perez today passes on to his own graduates, who regularly return to Monrovia High, where he moved into a roomy new studio two years ago. That open-door policy is only one of the classroom practices he inherited from his former professor. Hines, for example, always kept a full supply of what he called “the people’s clay,” for anyone who wanted to use it. Perez emulates the communal approach, assuring his students they don’t have to pay for materials if they can’t afford it.

“You can’t be selfish if you’re a teacher,” he says. “You make personal sacrifices and your own work has to take a back seat. What I find satisfying is when my students get recognition for what they’re doing here. There’s a different type of satisfaction that you get from that. In a sense, you live on through their work.”

Though it is set in Queens, Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s latest novel,

Though it is set in Queens, Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s latest novel,  A trustee since 1999, Buckley could have reasonably expected to be winding down, pulling back a bit, as she completes the final few years of her term. Instead, the Santa Rosa, Calif., resident agreed to step up to the role of board chair.

A trustee since 1999, Buckley could have reasonably expected to be winding down, pulling back a bit, as she completes the final few years of her term. Instead, the Santa Rosa, Calif., resident agreed to step up to the role of board chair.

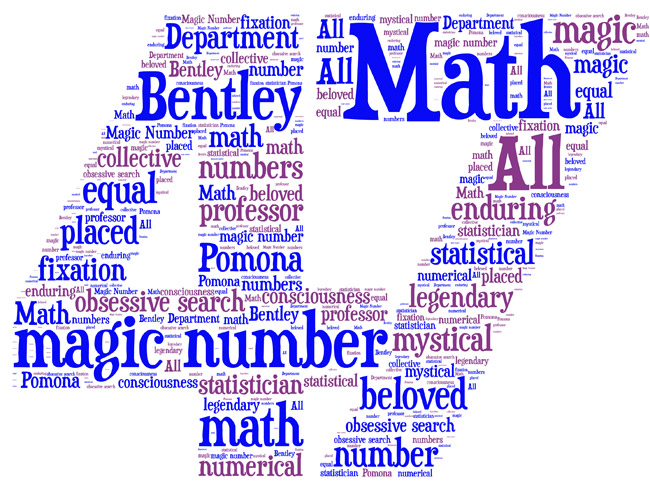

Don Bentley doesn’t want to talk about 47, the enduring numerical fixation the legendary math professor long ago placed in Pomona’s collective consciousness. It all started with a paradoxical proof Bentley put up on the chalk- board back in 1964, showing that all numbers are equal, which then morphed into all numbers equal 47—and spawned our endless, obsessive search for the magic number. But remember, Bentley doesn’t want to talk about that.

Don Bentley doesn’t want to talk about 47, the enduring numerical fixation the legendary math professor long ago placed in Pomona’s collective consciousness. It all started with a paradoxical proof Bentley put up on the chalk- board back in 1964, showing that all numbers are equal, which then morphed into all numbers equal 47—and spawned our endless, obsessive search for the magic number. But remember, Bentley doesn’t want to talk about that.

And we haven’t even covered the best part. Hawley returned to his alma mater in 1938, and his contributions over the next 24 years played a key role in the College’s rise. Launching what would later come to be known as the Pomona Plan, Hawley pioneered a game-changing vehicle in the world of educational fundraising. At the heart of what he hatched was this: a new kind of charitable-giving program in which the College, in essence, manages a donor’s money in return for a financial gift released to Pomona after the donor dies; the contributor earns a tax break and regular payments for the rest of his or her life.

And we haven’t even covered the best part. Hawley returned to his alma mater in 1938, and his contributions over the next 24 years played a key role in the College’s rise. Launching what would later come to be known as the Pomona Plan, Hawley pioneered a game-changing vehicle in the world of educational fundraising. At the heart of what he hatched was this: a new kind of charitable-giving program in which the College, in essence, manages a donor’s money in return for a financial gift released to Pomona after the donor dies; the contributor earns a tax break and regular payments for the rest of his or her life.