Nutritional Prejudice

Is Vitamin C better for you than an orange? Are omega-3 fatty acids more important for your diet than the fish they come from? This may sound like topsy-turvy nutritional logic, but a new study from Cornell University and Pomona College found participants judged individual nutrients as healthier than the whole, natural foods that contain them.

Published in the Journal of Health Psychology, the study by professors Jonathon P. Schuldt of Cornell University and Adam Pearson of Pomona College was sparked after the research partners read Michael Pollan’s book, In Defense of Food, in which the author speculates about an effect he dubs “nutritionism.”

Schuldt and Pearson devised a study to put this idea to the test: Two groups of research participants read an identical description of a moderately-healthy young man, but one group was told he made sure to include a variety of healthy foods in his diet, like bananas, fish, oranges, milk and spinach. For the second group, those foods were replaced with nutrients associated with those foods: potassium, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin C, calcium and iron.

The group that read about the nutrients considered the man to be at significantly lower risk of developing a number of leading chronic diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, cancer and stroke—and study participants who described themselves as diet-conscious or who had higher SAT/ACT scores were even more inclined to do so. The results aren’t surprising, Pearson said, in a society where people are constantly bombarded with health claims about nutrients and supplements. People who are more diet-conscious may be especially attentive to and influenced by these claims.

“It points to the insidious ways that the marketing of nutritional information can actually be harmful,” Pearson said. “If we are biased toward privileging the low-level properties of a food, we may overlook the many other healthy aspects of eating whole, natural foods.”

City of Trees

For their capstone project, a group of graduating seniors in Pomona College Professor Char Miller’s Environmental Analysis 190 class went out on a limb last spring and sought to map all of the public trees in the city of Claremont, sometimes called “The City of Trees and Ph.D.s.” The result is a convenient online guide mapping more than 24,000 trees and serving as an educational resource for the community.

Ben Wise of the Tree Action Group of Sustainable Claremont, a local nonprofit, contacted the Environmental Analysis (EA) Program and proposed that a team build a digital inventory and guide to city street trees. Wise’s aim was for people to see a tree in Claremont and then have a way to find out more about it.

So together, Alison Marks ’15, Naomi Bosch ’15, Nadine Lafeber SC ’15 and Sydney Stephenson CMC ’15—with help from geographic information system (GIS) specialist Warren Roberts at Honnold/Mudd Library—developed a website called Claremont Urban Arboretum (claremontsurbanarboretum.wordpress.com ) complete with an interactive GIS map and information on many of the life histories and origins of the tree species lining Claremont streets.

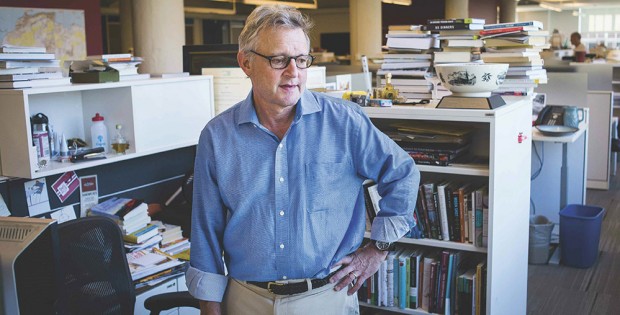

Environmental Analysis majors must complete two capstone projects: one individual and one group. “EA 190 is a group initiative defined by a real client with a real problem that must be resolved by the end of the spring semester,” says Miller, director of the EA Program. The aim is to push students to synthesize all they’ve learned over four years and translate that knowledge into action, he says.

Miller says public awareness about trees is a live issue, especially these days. “Claremont, the self-described City of Trees, has had a long love affair of the arboreal. But the current and crushing drought has made it essential that the community know more about the trees that are rooted into our stony soil,” he says.

Once Upon a Time in the Cambrian

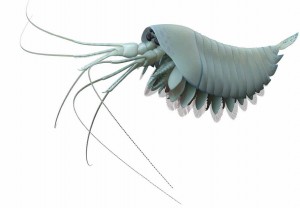

Once there was a lobster-like predator with two pairs of compound eyes and large, toothed claws that prowled the Cambrian seas. After its death, its fossil lay waiting in a place now known as Marble Canyon—a newly discovered part of the renowned Canadian Burgess Shale deposits—for more than half a billion years before a team of researchers, including Professor of Geology Robert Gaines, brought it to light once more.

In a paper published last spring in the journal Palaeontology, Gaines and his co-authors announced the discovery of this strange new creature, named Yawunik kootenayi. Gaines was also part of the team that discovered the Marble Canyon deposits last year.

Joe Palca’s cubicle in NPR’s Washington, D.C., headquarters is strewn with bicycle gear from his daily commute, assorted piles of books about science, and random objects: a can of mackerel, a leaf-shaped bottle of maple syrup. From this cluttered perch, the longtime science correspondent has the power to shape what becomes news. If Joe Palca ’74 decides a story is worth putting on the air, roughly a million listeners hear it. And if he misses a story, well, some of those listeners may never hear about it.

Joe Palca’s cubicle in NPR’s Washington, D.C., headquarters is strewn with bicycle gear from his daily commute, assorted piles of books about science, and random objects: a can of mackerel, a leaf-shaped bottle of maple syrup. From this cluttered perch, the longtime science correspondent has the power to shape what becomes news. If Joe Palca ’74 decides a story is worth putting on the air, roughly a million listeners hear it. And if he misses a story, well, some of those listeners may never hear about it. Of course, not all subjects have such inherent drama. Still, Palca says, scientists are not the cold-blooded, calculating creatures they are often presumed to be. “I’m sick of the caricature, of the white lab coat. The lab coat says ‘I’m an expert, not a person.’”

Of course, not all subjects have such inherent drama. Still, Palca says, scientists are not the cold-blooded, calculating creatures they are often presumed to be. “I’m sick of the caricature, of the white lab coat. The lab coat says ‘I’m an expert, not a person.’” On August 14, 2015, Burt Johnson’s 1916 sculpture “Spanish Music,” was reinstalled on the fountain in Lebus Court. The sculpture, which was a gift to the College from the Class of 1915, had remained in place in the courtyard until earlier this year, when a section of the fountain collapsed. Based on photographs of the original fountain, the fountain was rebuilt, and the College took the opportunity to have the statue restored and its broken flute repaired.

On August 14, 2015, Burt Johnson’s 1916 sculpture “Spanish Music,” was reinstalled on the fountain in Lebus Court. The sculpture, which was a gift to the College from the Class of 1915, had remained in place in the courtyard until earlier this year, when a section of the fountain collapsed. Based on photographs of the original fountain, the fountain was rebuilt, and the College took the opportunity to have the statue restored and its broken flute repaired.

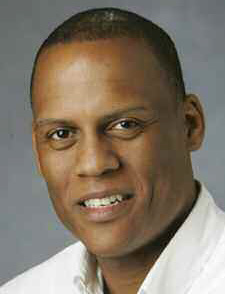

Suzanne Thompson, professor emerita of psychology at Pomona, conducts research on how people react to personal threats, particularly those with delayed consequences. She and her undergraduate research group are investigating a variety of ways in which different perceptions of threat influence the processing of threatening information and guide health and safety behaviors.

Suzanne Thompson, professor emerita of psychology at Pomona, conducts research on how people react to personal threats, particularly those with delayed consequences. She and her undergraduate research group are investigating a variety of ways in which different perceptions of threat influence the processing of threatening information and guide health and safety behaviors. If you are ever offered a tour of the new Millikan Laboratory and Andrew Science Hall with David Haley as your guide, take it. A 21-year veteran of physics departments, he has an enthusiasm for his subject that is nonstop and infectious. Completely at ease in the corridors of Millikan’s new underground laboratory, he misses no opportunity to point out the fascinating creations of Pomona students and faculty.

If you are ever offered a tour of the new Millikan Laboratory and Andrew Science Hall with David Haley as your guide, take it. A 21-year veteran of physics departments, he has an enthusiasm for his subject that is nonstop and infectious. Completely at ease in the corridors of Millikan’s new underground laboratory, he misses no opportunity to point out the fascinating creations of Pomona students and faculty. Board Chair Samuel D. Glick ’04

Board Chair Samuel D. Glick ’04

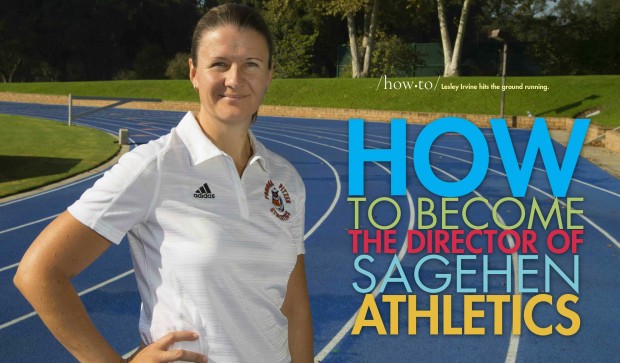

There’s nothing particularly surprising in the fact that Pomona-Pitzer’s new athletic director has hit the ground running. Lesley Irvine has been moving fast ever since she was a child—first as a multi-sport athlete, then as a high-profile coach and finally as an athletic administrator. At Pomona, she has assumed a newly created full-time position as chair of Pomona’s Physical Education Department and director of the joint athletic program of Pomona and Pitzer colleges.

There’s nothing particularly surprising in the fact that Pomona-Pitzer’s new athletic director has hit the ground running. Lesley Irvine has been moving fast ever since she was a child—first as a multi-sport athlete, then as a high-profile coach and finally as an athletic administrator. At Pomona, she has assumed a newly created full-time position as chair of Pomona’s Physical Education Department and director of the joint athletic program of Pomona and Pitzer colleges. Grow up in Corby, a steel town in central England where most people are of Scottish descent and speak with a Scottish brogue. Develop into an active child, always sporting a scraped knee. Get involved in athletics with the encouragement of your dad, an avid soccer player, coach and fan.

Grow up in Corby, a steel town in central England where most people are of Scottish descent and speak with a Scottish brogue. Develop into an active child, always sporting a scraped knee. Get involved in athletics with the encouragement of your dad, an avid soccer player, coach and fan. Join a track and field club at the age of 9 and, since you excel in a range of athletic events, specialize in the heptathlon. In high school, find yourself playing almost every sport, from basketball to volleyball to soccer. Discover the game of field hockey and fall in love with it.

Join a track and field club at the age of 9 and, since you excel in a range of athletic events, specialize in the heptathlon. In high school, find yourself playing almost every sport, from basketball to volleyball to soccer. Discover the game of field hockey and fall in love with it. Accept an invitation to play on the English junior national field hockey team at the age of 16, while also competing internationally in the heptathlon. Play for England in a victory over Scotland in the Six Nations field hockey tournament and have to explain to your teammates why your dad, a proud Scot, is rooting against you.

Accept an invitation to play on the English junior national field hockey team at the age of 16, while also competing internationally in the heptathlon. Play for England in a victory over Scotland in the Six Nations field hockey tournament and have to explain to your teammates why your dad, a proud Scot, is rooting against you. Become the first member of your family to go to college, playing field hockey at prestigious Loughborough University. While there, win five national championships. During your second year, teach tennis at a summer camp in Maine (though you’ve never touched a tennis racquet before) and find yourself at home in American sports culture.

Become the first member of your family to go to college, playing field hockey at prestigious Loughborough University. While there, win five national championships. During your second year, teach tennis at a summer camp in Maine (though you’ve never touched a tennis racquet before) and find yourself at home in American sports culture. After graduating, come back to the U.S. for graduate school, attending the University of Iowa and playing competitive field hockey for one more year, scoring the only goal in a 1–0 victory over Stanford University in your first trip out West and leading your team to a Final Four appearance. Earn your master’s degree in health, leisure and sports studies.

After graduating, come back to the U.S. for graduate school, attending the University of Iowa and playing competitive field hockey for one more year, scoring the only goal in a 1–0 victory over Stanford University in your first trip out West and leading your team to a Final Four appearance. Earn your master’s degree in health, leisure and sports studies. Return to Stanford as assistant women’s field hockey coach. Discover that you love working with committed student athletes who love sports as much as you do. After two years, succeed the retiring head coach and spend eight years at the helm of Stanford’s elite program, guiding them to three straight NorPac championships.

Return to Stanford as assistant women’s field hockey coach. Discover that you love working with committed student athletes who love sports as much as you do. After two years, succeed the retiring head coach and spend eight years at the helm of Stanford’s elite program, guiding them to three straight NorPac championships. Leave Stanford to enter sports administration, spending five years at Bowling Green State University and rising to the rank of senior associate athletic director. Decide the job at Pomona-Pitzer is a perfect match for your abilities and your desire to help build something special for talented and motivated student-athletes while promoting wellness for a whole community

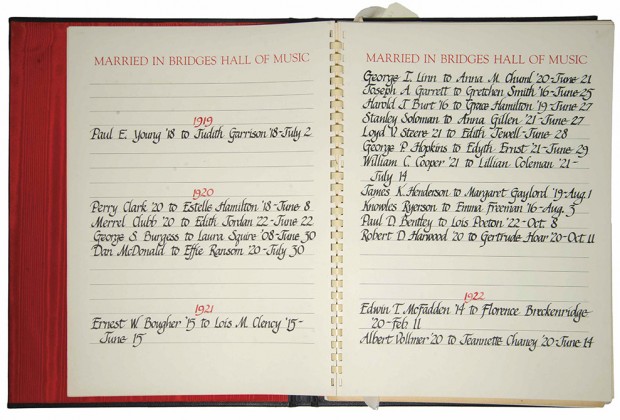

Leave Stanford to enter sports administration, spending five years at Bowling Green State University and rising to the rank of senior associate athletic director. Decide the job at Pomona-Pitzer is a perfect match for your abilities and your desire to help build something special for talented and motivated student-athletes while promoting wellness for a whole community As Bridges Hall of Music celebrates its centennial, many Pomona alumni look back fondly at the place where they said “I do.” The Little Bridges Wedding Register is a historical record of marriages that took place in the building, starting with Howry Warner 1912 and Mary Roof 1912, married June 1, 1916. Compiled in the early 1970s, the register was maintained and updated through 1992 and includes the names of 453 couples.

As Bridges Hall of Music celebrates its centennial, many Pomona alumni look back fondly at the place where they said “I do.” The Little Bridges Wedding Register is a historical record of marriages that took place in the building, starting with Howry Warner 1912 and Mary Roof 1912, married June 1, 1916. Compiled in the early 1970s, the register was maintained and updated through 1992 and includes the names of 453 couples.