Emily Post’s Etiquette By Peggy Post, Anna Post, Lizzie Post and Daniel Post Senning ’99 William Morrow, 2011 736 pages • $39.99

As the great-great-grandson of the world’s most famous expert in etiquette and a fifth-generation steward of “the family business,” Daniel Post Senning ’99 is a co-author of the 18th edition of Emily Post’s Etiquette. He and his cousins Anna and Lizzie Post are part of a new generation working to keep that classic work relevant in the 21st century.

PCM: Today the word ‘etiquette’ has an old-fashioned ring. Is that justified?

Daniel Post Senning: It’s certainly a perception that I’m used to. The Emily Post Institute is a five-generation family business. The original Emily Post was my great-great-grandmother, and she wrote the first edition of Etiquette in 1922.

If you were to pick up that book today, it would read like a historical document. It’s actually quite remarkable as that. There are people who love looking at etiquette books that have been produced throughout history. One of my favorites, Castiglione’s The Courtier, predated The Prince. Oftentimes, a good book of etiquette will tell you a lot about a culture or a time.

We are very fortunate to be part of a tradition that has continued to update that original book. It was incredibly popular in its time. They couldn’t print it fast enough. But as times changed, they found that it was absolutely necessary to revise it. It’s that process of revision that I think has really become the substance of what we do at The Emily Post Institute.

PCM: Define ‘etiquette’ for me.

DPS: We say that etiquette is a combination of manners and principles. For us, the manners are time-, location- and culture-specific. They’re the particular expectations we have of others and ourselves in a particular social situation. The principles are what we use to guide us as manners change and evolve, or to help us make choices when we’re in a new situation. For us at the Emily Post Institute, the fundamental principles for all good etiquette are consideration, respect and honesty.

Here’s an Emily Post quote for you, “Any time two people come together and their lives affect one another, you have etiquette.” Etiquette is not some rigid code of manners. It’s simply how persons’ lives touch one another. Any time you have people interacting, you’ve got social expectations.

PCM: So how do you become an expert on etiquette? Is it something you just absorb?

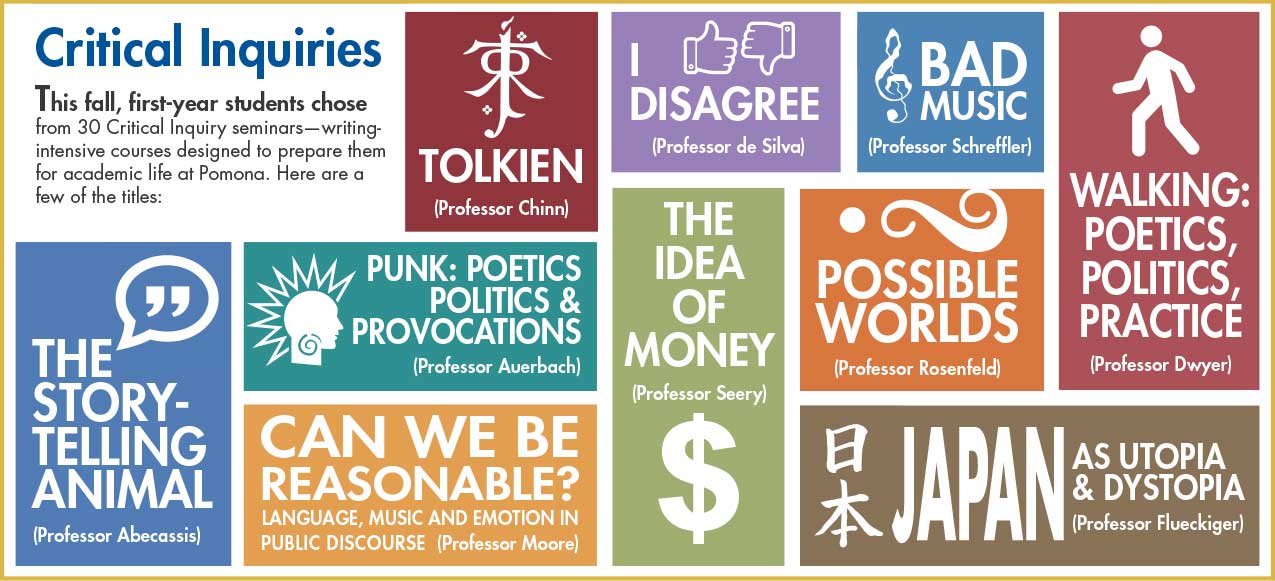

DPS: I never thought a liberal arts education would prepare me so well for the work that I do. Being someone who writes about etiquette, researches about etiquette, teaches about etiquette, I find myself drawing from so many disciplines and so many skill sets. When I’m teaching and I’m presenting, my background in dance and the performing arts comes out. When I’m doing research, my background in critical inquiry comes out. When I’m assessing a new study that we’re getting, and I’m looking at data that’s come in from our survey partners, my background in microbiology and having the ability to look at data sets come into play.

Let me tell you a personal story. I was living in Claremont, working with the Laurie Cameron Company out of the Pomona College Dance Department, when I first started working for Emily Post. At the time, I was answering questions via email. My cousins and I cut our teeth on those emails. We would get batches of questions. We’d go through the books. When there was a particular question that had a historical precedent—questions about how you use formal titles or orders of introduction or protocol and courtesy around weddings—oftentimes we would refer to the book and find an answer that was pretty concrete.

Other times, there are relationship situations that people are trying to resolve, and that framework of consideration, respect and honesty comes into play. You ask yourself: Is the advice that I’m giving considerate? Is it taking into account all the people who are involved? Is it respectful? Is it recognizing their worth and their value? Is it honest? Is it something I can do with a sense of integrity and sincerity? It’s really a pretty powerful framework to give advice from.

PCM: How much of etiquette is timeless and how much do you believe is bound to the times?

DPS: Our whole approach is that etiquette is a moving, living, breathing thing. It changes and evolves all the time. That’s why the book is currently in its 18th edition. It’s never been out of print, and we think that’s really important. That’s why it’s important to continue to update it, because it is a moving target. If it were to ossify, it would lose its meaning very quickly.

When you look at the 1922 edition of Etiquette and the 18th edition of Etiquette, there’s some material that looks remarkably similar. You can probably guess that the way my great-great-grandmother described using a knife and fork is very similar to the way I would describe that today. Manners around how we share food and how we eat change relatively slowly. Those are cultural expectations that are very firm. The ones that we see changing the most rapidly are manners around communication.

PCM: So, do you have etiquette suggestions for Twitter?

DPS: We absolutely do. The framework that we use is relationships. When you’re assessing behaviors around new communication technology, you use the relationship as your guide. My cousin Anna’s really good at this. When she’s presenting, she’ll take her phone, hold it up and say, “This is my phone. It’s the newest, the latest, the greatest. It’s amazing. I can do incredible things with it. It’s not rude. It’s not polite. It’s how I use it that matters.” If you think about the relationships that are being impacted and affected, it helps you make good choices in those environments.

PCM: Still, there’s a lot of rudeness out there in cyberspace. Do you think this is a particularly bad-mannered period in history?

DPS: Sometimes we hear from people, “Oh, there are no manners today; manners are in a state of decline.” One of the nice things about having a generational perspective on this work is that every generation perceives that to be true, witnesses the changes that occur over time and thinks that the state of manners are in decline.

Like so many things in life, I really think of it as a pendulum. I think that people challenge and push the boundaries, and then there’s a response. New structures come into being. I think the generation that had the most difficult time with this was my parents’ generation, and even my grandmother, who was writing in the late ’60s and early ’70s. You had a generation that was intentionally trying to deconstruct the social order at that time.

I don’t think that happens in the same way right now. Quite the contrary, I think we might be in a time where, because there is so much choice, because we do live in an increasingly casual and informal world, people are looking for information to help them make choices in that environment.

PCM: You said it’s mostly about relationships. But a lot of modern communication is more like broadcasting. Emily Post didn’t have to worry about the etiquette of announcing one’s foibles to seven billion people around the world.

DPS: Absolutely, but here, too, there are lessons to be learned from the past. When I teach conversation skills, I’ll teach three tiers to a conversation. Tier one is safe territory—sports, the weather, pop culture, local celebrities, what you had for breakfast that morning. Tier two is potentially controversial. People have different and valid opinions about these topics. They were not table talk. They were reserved for private conversation—religion, politics, dating, your love life. The third tier, the most intimate, is family and finance. You don’t ask probing questions or offer too much information unless someone has already opened the door to that in some way.

Those rules for conversation around a dinner table or in the workplace function very well for the online space, where you’re talking about a much bigger conversation, but one where a sense of discretion and propriety are really important.

One of the immediate associations people often have with etiquette is that it’s common sense or that it’s the Golden Rule. It’s treating other people the way you’d want to be treated. You hear that a lot. I like to emphasize the Platinum Rule these days, the evolution of the Golden Rule. In an increasingly diverse and complex world, it’s really important to treat other people the way they would want to be treated. It’s no longer enough to go around applying your own standard to everybody that you meet. You need to make an effort also to take into account the different standards that different people have. That’s a challenge for all of us to continue to push ourselves to be aware of not just our own perspective, but that of others as well.

PCM: So what’s the future of etiquette?

DPS: Sometimes people ask me, “What would success look like in this business?” and I say, “If I can be a steward for this tradition, if I can hand it off to the sixth generation, I’ll absolutely consider that a success.”

We’re approaching the hundredth anniversary of the original publishing of Etiquette. The 20th edition will be out in 2022. They stopped, as you know, publishing Encyclopedia Britannica a couple of years ago. Being in the publishing industry, particularly publishing reference books, is a really challenging thing.

One of the challenges for our generation has been figuring out how to not just continue to evolve our content, but also to continue to find new mediums for it. The vehicle that I most like to promote these days is a podcast that I’m doing with my cousin Lizzie called Awesome Etiquette. It’s produced by American Public Media, the folks that do Marketplace, and Prairie Home Companion, and Splendid Table. It’s a Q and A show, kind of a Car Talk of etiquette.

To me, Emily was also a radio star. She was a lifestyle personality who was recognizable across America. The return of Emily Post to radio, I think, is a really big deal for us.

PCM: But is the printed book still the core of the business, or is it becoming less important?

DPS: It’s the backbone of what we do. There have been other etiquette experts who have done amazing work. A contemporary of Emily’s, Amy Vanderbilt, produced an amazing book. Letitia Baldrige in the 1960s, the Kennedy White House social secretary—her book is also very good.

Emily Post’s Etiquette is unique in the fact that we are a reference book that has continued to change and evolve, and has been in print for over 90 years now. There is no replacing that. We sometimes call ourselves a social barometer. In figuring out which manners have lost their utility and have gone out of fashion and which are emerging and coming into being, the process of editing and rewriting that book every five to seven years is substantively the most important work that we do.

GOLD

GOLD

If you’re comparing yourself to others, you’re often going to find yourself short on something, especially if they have a background that’s different from your own. … Don’t measure yourself against others. Measure yourself against you. How much have you done to get where you are? And take pride in that, because that adds to the richness of your university and the place that you’re in.

If you’re comparing yourself to others, you’re often going to find yourself short on something, especially if they have a background that’s different from your own. … Don’t measure yourself against others. Measure yourself against you. How much have you done to get where you are? And take pride in that, because that adds to the richness of your university and the place that you’re in. For nearly 20 years, the Pomona College Museum of Art has been home to a series of exhibitions designed to turn a spotlight on emerging and underrepresented artists from Southern California. After 49 exhibits in what became known as the Project Series, senior curator Rebecca McGrew ’85 decided to take it up a notch for Project #50 by showcasing seven artists in concurrent solo exhibitions in “R.S.V.P Los Angeles,” which will be open through Dec. 19. “I envisioned collaborating directly with the artists who themselves were engaging with the contemporary cultural moment through a rich, boundary-blurring dialogue of art, culture, history, social issues, politics, music, science and more,” says McGrew on how the Project Series was conceived in 1999. Many of the artists who have been featured in the series have gone on to major national recognition.

For nearly 20 years, the Pomona College Museum of Art has been home to a series of exhibitions designed to turn a spotlight on emerging and underrepresented artists from Southern California. After 49 exhibits in what became known as the Project Series, senior curator Rebecca McGrew ’85 decided to take it up a notch for Project #50 by showcasing seven artists in concurrent solo exhibitions in “R.S.V.P Los Angeles,” which will be open through Dec. 19. “I envisioned collaborating directly with the artists who themselves were engaging with the contemporary cultural moment through a rich, boundary-blurring dialogue of art, culture, history, social issues, politics, music, science and more,” says McGrew on how the Project Series was conceived in 1999. Many of the artists who have been featured in the series have gone on to major national recognition.

Working Through the Past

Working Through the Past