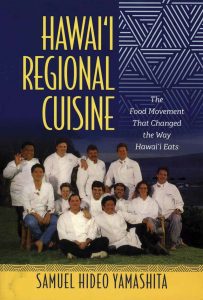

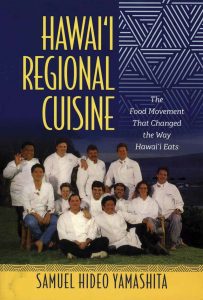

Odds are high that food is one of your favorite topics. Office conversations about where to go for lunch. Calls home on your commute asking what’s for dinner. Recounting a delicious meal in meticulous detail to a friend. Binging on the Food Network. And, of course, your Instagram feed (no pun intended). Food is a near and dear topic for Samuel Yamashita, too. The Pomona College Henry E. Sheffield Professor of History combined two great loves—food and, of course, history—and wrote Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine: The Food Movement That Changed the Way Hawai‘i Eats. In the book, Yamashita chronicles the way Hawaiians have eaten over time, and the way good, local island eats combined with French and Continental mainland fare to create a distinctive style of cuisine.

Odds are high that food is one of your favorite topics. Office conversations about where to go for lunch. Calls home on your commute asking what’s for dinner. Recounting a delicious meal in meticulous detail to a friend. Binging on the Food Network. And, of course, your Instagram feed (no pun intended). Food is a near and dear topic for Samuel Yamashita, too. The Pomona College Henry E. Sheffield Professor of History combined two great loves—food and, of course, history—and wrote Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine: The Food Movement That Changed the Way Hawai‘i Eats. In the book, Yamashita chronicles the way Hawaiians have eaten over time, and the way good, local island eats combined with French and Continental mainland fare to create a distinctive style of cuisine.

PCM’s Sneha Abraham sat down for a chat with Yamashita on all things food.

PCM: You grew up on the Hawaiian Islands?

Yamashita: I did. I grew up in a suburb of Honolulu, a place called Kailua, which has one of the most beautiful beaches in the world, top 10. And it’s where Obama would rent a house during his presidency, but, of course, he really couldn’t go on to the beach because of too many people.

PCM: Security.

Yamashita: Yeah. So, I grew up in a beach town. I didn’t really wear shoes until I was 12. And so I had huge feet with really hard, kind of leathery soles. I had a great childhood. I mean, I played, I fished. I didn’t study much.

PCM: You’ve made up for it in the years since.

Yamashita: Well, I had to.

PCM: Were you born there as well?

Yamashita: I was born in Honolulu, in the same hospital where Obama was born.

PCM: What inspired you to do food studies?

Yamashita: In about 2007 or ’08, my editor at the University of Hawai‘i Press asked me out of the blue if I’d be interested in writing the history of Japanese food. She knew I was interested in food, and she was too. We’d have great lunches, and it was at the end of one of these celebratory lunches (on the occasion of the publication of my book Leaves from an Autumn of Emergencies, that she oversaw) that she asked me, “How would you like to write a history of Japanese food?” I was old enough to know that I really needed to think about this. To think about what sources I would use, how I would organize it, what kinds of narratives I would write. And I said, “Let me think about this.”

I thought about it for half a year, and then I said, “Sure, I’d be happy to give it a try.” But I said, “You and I know that you’ll be long retired by the time I finish.” She was exactly my age, and I sensed that she was going to retire in a few years, and I was right. So she retired about four or five years ago, and I’ll finish this history of Japanese food in 2025 or so. It’ll probably be my last book. That was the beginning of my interest in food studies.

I also had collected and read many dozens of wartime Japanese diaries and had written some pieces on the food situation in Japan during World War II. My first food pieces were actually on the food situation in wartime Japan. And then in around 2009, or ’08 maybe, I was having to visit my widowed father in Hawai‘i about four times a year, and I thought, “I need to be able to write off these trips.”

So I began to interview chefs—the chefs for the Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine movement. And I ended up interviewing 36 people, including eight of the 12 founding chefs of Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine. And then I wrote a paper called “The Significance of Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine in Post-Colonial Hawai‘i” and presented it at a conference, and somebody who heard it said, “How would you like to contribute it to a volume?” And so a volume called Eating Asian America was assembled and published by NYU in 2013. That was another important piece for me. And then I began to map out a book on Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine. And in the meantime, I published in 2015 a book called Daily Life in Wartime Japan, 1940–1945 that used about 100 of the diaries I collected.

Once I finished with that, then I was able to concentrate on what became Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine. I’ve also had good support from the College, chiefly in the form of the Frederick Sontag research fellowships, which are for senior faculty. So without those and without a series of spring leaves, I wouldn’t have been able to finish.

PCM: Talk about the perceptions of Hawaiian food that you write about.

Yamashita: Well, people who traveled to Hawai‘i didn’t go for the food, and Alice Waters once said to a friend, “If you go to Hawai‘i, be sure to take some good olive oil and vinegar so you can make a dressing and buy some watercress and have a good salad at least”—right? That was the prevailing view—that you went to Hawai‘i to spend time at the beach, to do other fun things, but not to eat. And the one food phenomenon that was somewhat popular was the so-called luau, a kind of Hawaiian feast. And I certainly grew up attending luaus because our Hawaiian friends and neighbors would usually have a luau whenever there was something to celebrate. When a new child was born or a child graduated from high school or somebody got married or when there was a new baby, often there’d be a luau. And this is pretty typical of the Pacific and parts of Southeast Asia—you raise a pig especially for the luau, and the pig is ready at a certain point, and it becomes the main item in the luau. And so, our neighbors would dig an underground pit called an imu, and they cooked the pig in the pit. They’d also make all sorts of dishes that accompanied it, including poke, which is very popular now in the U.S., but poke was … I could never eat poke outside Hawai‘i. Often they misspell it, P-O-K-I; it’s really P-O-K-E.

PCM: People here pronounce it poke-EE, too, right?

Yamashita: Yeah, yeah, it’s po-KEH. So, I’d say Alice Waters’s characterization of food in Hawai‘i and then the construction of the luau as a tourist food event were probably the two prevailing views of food in the islands. And, of course, as I point out in my book, there was fine dining in the islands, usually at the top hotels that would hire Anglo chefs, usually European or American French-trained chefs. And what’s interesting is that they would cook the very same things that their counterparts on the mainland or in Europe cooked. They would make the same French dishes, and they would use imported, generally imported fish, meat, vegetables and things of that sort. They weren’t using local, locally sourced ingredients much at all. And, of course, all the chefs, all the top chefs were Anglo, and locals served in subordinate positions as cooks.

So-called “local food” is the food that the local ethnic communities brought to Hawai‘i when they immigrated. The food they ate was denigrated by these Anglo chefs. So, there was a pretty stark hierarchy that separated haute cuisine, which was French and continental, from local food.

PCM: Can you talk a little bit about colonialism and then food, that relationship?

Yamashita: In almost all colonial situations, the food of the colonial masters is valued and elevated and affirmed. Of course, it is served in the homes and in the clubs of the colonial elite, and local food is denigrated. I have cookbooks from the 19th century and the recipes are typical of New England. And they added a few Hawaiian things, but about 96 percent, 97 percent of the dishes in those cookbooks were American.

There’s a scholar whose work I admire named Zilkia Janer who has written about food in Central America and Latin America. And, of course, there it’s the Spanish cuisine that’s elevated, and local cuisine of local indigenous people was denigrated. I actually use her piece in my book, as well as a number of other works on colonialism in South Asia, which offer a framework. So I also placed Hawai‘i in that broader colonial context.

PCM: Do you think we’re seeing kind of an iteration of that today in terms of globalization—the standard American diet is being adopted across the world?

Yamashita: Globalization is spreading American fast food as well as American popular culture. So McDonald’s is in many places, even places where you don’t expect to find it. Of course, now it’s almost everywhere. And that’s very typical, but it’s a new kind of colonialism; it’s a latter-day, postmodern colonialism that’s a little different from what existed earlier.

PCM: Talk a little bit more about the historical distinctions between fine-dining food versus local food. What dishes did you find in fine dining? What dishes in local food?

Yamashita: Before Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine?

PCM: Yes.

Yamashita: So essentially, fine dining was dominated by continental and/or French cuisine. And so lots of emphasis on heavy sauces, as was the case with the French cuisine served with imported wines. Usually not served with rice, but with potatoes. I analyzed menus from some of the top restaurants in the islands before HRC, and the menus would be recognizable to anyone familiar with fine dining on the mainland as well. It’s actually what you would find at top fine-dining establishments, especially French restaurants, in New York, in San Francisco and in Chicago. And you wouldn’t find local dishes on the menu.

What really suggested to me that something had happened was the following: My wife and I went to this really wonderful, well-regarded restaurant called CanoeHouse on the Big Island. It’s a great place for a great romantic dinner, located close enough to the ocean that you would hear the surf breaking. We got there at dusk and were led to a table and sat down, and I noticed on the table what you would find in the homes of locals and especially working-class locals—bottles of soy sauce and chili pepper water. And so when the waitress came back to the table, I said, “What’s this? What’s going on?” And she said, “Oh, we have a new chef. His name is Alan Wong.” That’s the two-word answer to the question. The bigger answer, the fuller answer is Hawaiian Regional Cuisine. Suddenly, people like Alan Wong and Roy Yamaguchi made it possible for local food to find its way into fine-dining establishments and, of course, this is what triggered my interest.

PCM: What did the chefs say triggered it for them?

Yamashita: Oh, that’s a good question that has several different answers. Let me give you the big answer first. Roy Yamaguchi graduated from the Culinary Institute of America, 1976. He was one of the first students of Asian descent to go there, you know—CIA in Hyde Park, New York. And after he graduated, he came to L.A. and cooked at a number of different places, finding his way in the restaurant world because there weren’t many Asian chefs. And he ended up finally at the best French restaurant in Los Angeles.

Then he cooked at two other French restaurants. And food critics writing for the Los Angeles Times wrote reviews of those restaurants and they said, “You know, I had the best French dinner I’ve had all year at this restaurant,” and who was the chef? It was Roy Yamaguchi. And then in 1984, he opened his own restaurant called 385 North, which was located at 385 La Cienega in West Hollywood. But what was also happening is that in 1982, Wolfgang Puck opened Spago, and then in 1983, he opened Chinois on Main, and then a bunch of Japanese chefs sent from Japan opened Franco-Japanese restaurants. And then Roy opened 385 North, and they were all cooking something that Roy called “Euro-Asian cuisine.” And he claims to have invented the concept in 1980; he may have invented it, but it quickly spread and was adopted by Puck and these other Japanese chefs.

Nobu Matsuhisa opened Matsuhisa in 1985, just about half a mile south of 385 North. But they were all doing Euro-Asian cuisine. And then in 1988, Roy came back to Hawai‘i and opened his own restaurant called Roy’s, and he used the Euro-Asian cuisine concept. And what that made possible was the adoption by chefs at fine-dining establishments of all kinds of Asian ingredients, the serving of Asian dishes. Conceptually that was what made HRC possible at a very high level. Because Roy was extremely well-trained and had experience and came to Hawai‘i, and that Euro-Asian framework was adopted by the other HRC chefs as well.

But at another level, if you asked Alan Wong that question, he would say something different—Alan Wong and Sam Choy, who were the two of the 12 chefs who are local. Alan Wong would say, “This is plantation food,” because the plantation communities were multi-ethnic.

Alan puts it this way: “You know, they would share their lunches, and so the Japanese would bring a Japanese lunch, the Chinese would bring a Chinese lunch, the Filipino would bring a Filipino lunch, and they would share food.” And so, Alan’s answer then is, “Well, this is what happened historically in Hawai‘i, beginning in plantation times.” It’s a very different kind of answer, but Alan did not go to the CIA. Alan went through a culinary arts program at a community college in Hawai‘i for two years, and then he went to a famous resort in Virginia called the Greenbrier, where he had two more years of training. And then he worked in New York at Lutèce, which was one of the best French restaurants in New York City. And after several years there, he then came back to Hawai‘i.

So he had the technical skill to make the best possible French cuisine imaginable, but he began to incorporate things from the local diet. That’s how he would explain that. So two very different kinds of answers. I think Alan’s answer is somewhat mythicized; it’s a kind of romantic view of Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine. I think the story of Roy is one that, historically, I’m more comfortable with. You know, I don’t like myth.

PCM: Yeah, you deal in history.

Yamashita: Yeah, that’s right, exactly right.

PCM: There is a sort of farm-to-table element, right, in Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Yamashita: Well, that emerges somewhat late. Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine—its founding is formally announced in August 1991. It’s really not until the second decade, in the 21st century, that Peter Merriman and others developed the farm-to-table dimension of Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine. Of course, farm-to-table also emerges on the mainland, the continental U.S., around the same time—I think in the 21st century. And, you know, it’s important, but the impact of Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine on farming is actually much larger than that because farm-to-table is a kind of tourist phenomenon, right? It’s so that tourists can visit the farms with the chef and meet the farmers and so forth. What Peter Merriman and others began to do in the 1990s was to develop relationships with farmers. What it does is to encourage local farmers, and it makes possible a kind of locavorism that was beginning to be really big on the mainland as well.

PCM: What is the legacy of HRC?

Yamashita: Good, good—that’s an important question. In the first place, Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine has made haute cuisine in Hawai‘i part of what I call “the restaurant world” on the mainland, and this was very important. That is, they were noticed by mainland food writers and won national awards. Secondly, it affirmed locavorism and encouraged local farmers such as Tane Datta. His daughter’s name was Amber. I think she was a 2013 Pomona graduate. Third, Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine affirmed “local food,” in quotation marks—that is, the food that local people, non-Anglo people, ate. Fourth, it led to the formation of farmers’ markets throughout the islands. Fifth, it made culinary arts an acceptable path of study, and even graduates of Punahou [a prestigious private K–12 school in Honolulu] became chefs—Ed Kenney and Michelle Karr-Ueoka, they’re both Punahou graduates. In the sixth place, HRC helped de-racialize fine dining in the islands. And that’s, to me, a really important point. Roy Yamaguchi says, “In an earlier generation, I would’ve been a cook, not a chef.” So he’s aware of that demographic change.

It also helped shatter the domination of French cuisine. And I was able to track this in recipes of HRC chefs. And that connection made it easier for chefs in the islands to cook locally, to cook things inspired by what they grew up with in their respective ethnic communities. One of the post-HRC chefs, the Filipino chef Sheldon Simeon, says, “I’m cooking my community.” Which I thought was a wonderful way to put it: “I’m cooking my community.” And then finally, the HRC movement and chefs brought important food issues to the attention of the broader public. So, sustainability, obviously, is one important issue.

There’s a kind of bottom fish called pink snapper; it and other types of bottom fish were being overfished. And so HRC chef Peter Merriman brought that to the attention of the broader public in some editorials that he wrote. And this resulted in careful regulation of bottom fish catches. When a certain limit is reached, then they close it down. And some of the chefs even began to use farm-raised tilapia instead of pink snapper.

Tilapia can be farmed. And apparently, the farmed tilapia tastes good. Whereas the tilapia that some of us caught when we were kids, you know, it tasted muddy, it tasted like catfish. So, it’s had a huge impact. And, of course, the HRC chefs became celebrities, got TV shows and contracts. And so, they became part of this global celebrity-chef phenomenon. Yeah, big deal.

PCM: Yeah, it is. What was the most fun part about writing this book?

Yamashita:: Well, of course, eating the food.

PCM: I knew the answer, but I had to ask. Do you have a favorite Hawaiian dish?

Yamashita: A favorite dish? Well, you know, Alan Wong’s loco moco was my all-time favorite dish.

Alan Wong’s interpretation of loco moco

PCM: Can you describe for the readers what loco moco is?

Yamashita: Well, it’s an interesting story because the loco moco was invented in Hilo, after World War II. And it was a dish created for a bunch of local teenage boys who were about to play a football game. A particular cook said, “I’ll make a dish for you guys.” It’s a plate with a mound of cooked short grain rice, topped with a hamburger patty with brown gravy poured over it and a fried egg on top. So they got starch, they got protein, you know, and lots of carbohydrates, and that carried them through the game. And so if you go to L&L Drive-In, they serve loco moco.

What Alan Wong did was to deconstruct the loco moco. For the rice, he used mochi rice, which is a highly glutinous rice. He cooked it and then created a kind of patty, rice patty, and deep fried it briefly. And then, instead of the ground beef patty, he used ground wagyu beef and unagi, which is Japanese eel. Mixed that together, created a patty, and cooked that and slathered it with an unagi sauce, which is sauce made with soy sauce and sake, and probably sugar. It’s a thick, dark sauce. He poured that over it, and then he topped it with a fried quail egg. There’s a picture of it in my book, and it’s a magnificent, brilliant, brilliant take on a humble local dish. I had eaten several different loco mocos of Alan Wong’s over the years before I encountered the version I just described. This was, to me, the pinnacle.

PCM: Loco moco 2.0.

Yamashita: Loco moco 4.0.

PCM: Do you cook?

Yamashita: You know, I do, or I used to. My wife’s such a good cook that I leave it up to her. No, I like to cook the things that are my favorites.

PCM: What’s your signature dish?

Yamashita: I used to have my students over, and what I used to make was a beef carbonnade described in a French cookbook. It’s essentially a stew made with beef and onions and a lot of red wine. It’s just a really hearty, rich dish, but a lot of our students are vegetarians, so they didn’t always like that, but that was what I used to make.

At that point I started making instead a Chinese dish called white-cooked chicken, where you parboil chicken and serve it at room temperature, and you slice cucumbers into thin strips and put the chicken on top of that and serve it with a peanut sauce.

PCM: That sounds delicious.

Yamashita: That’s one of my favorites. So, when I’m a bachelor, I often make that for myself.

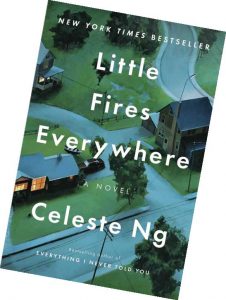

The fall selection of the Pomona College Book Club has been getting rave reviews, like this one:

The fall selection of the Pomona College Book Club has been getting rave reviews, like this one:

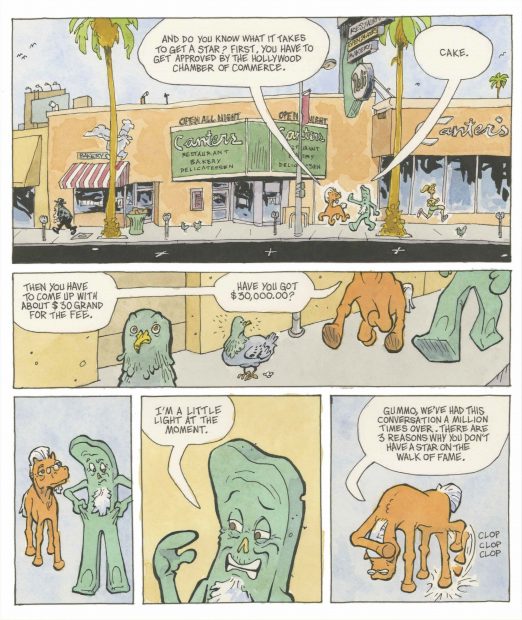

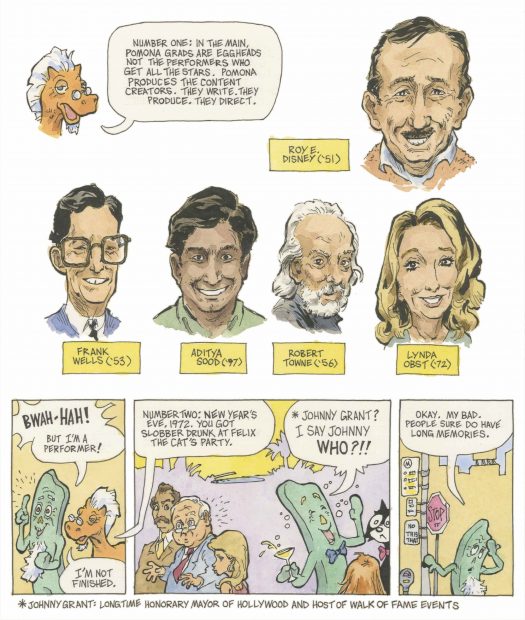

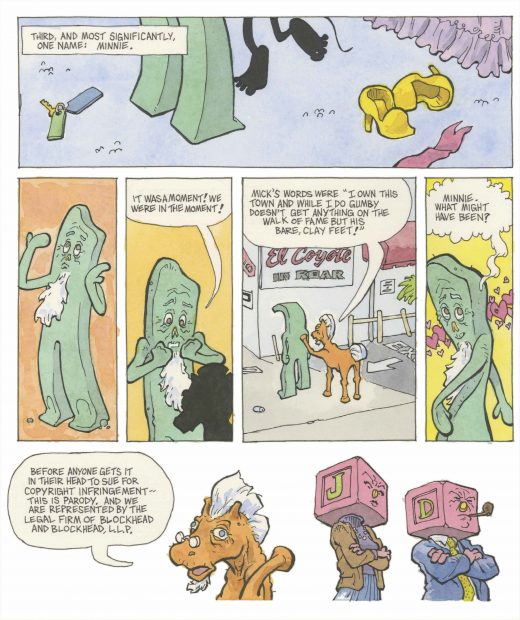

ON A RANDOM weeknight at a comedy club in Burbank, Pomona College Professor Ori Amir bounds onto the stage.

ON A RANDOM weeknight at a comedy club in Burbank, Pomona College Professor Ori Amir bounds onto the stage. Amir’s research has been featured by Forbes, and the journal Nature reported on his work last fall in an article about how neuroscience is breaking out of the lab, citing his doctoral research at the University of Southern California with Irving Biederman on the neural correlates of humor creativity. The Guardian, Reader’s Digest and the website Live Science also have featured Amir’s work.

Amir’s research has been featured by Forbes, and the journal Nature reported on his work last fall in an article about how neuroscience is breaking out of the lab, citing his doctoral research at the University of Southern California with Irving Biederman on the neural correlates of humor creativity. The Guardian, Reader’s Digest and the website Live Science also have featured Amir’s work.

The results were then compared to something called a saliency map of the cartoon image.

The results were then compared to something called a saliency map of the cartoon image. “You don’t know the path,” he says. “The path is—you’re going to end up performing for a long time in front of three apathetic strangers at an open mic, and you’re going to wait two hours to do that and have to buy something from the place. Especially in Los Angeles, it’s an extremely competitive sort of thing. But obviously if it wasn’t so rewarding, people would not be working with so much effort.”

“You don’t know the path,” he says. “The path is—you’re going to end up performing for a long time in front of three apathetic strangers at an open mic, and you’re going to wait two hours to do that and have to buy something from the place. Especially in Los Angeles, it’s an extremely competitive sort of thing. But obviously if it wasn’t so rewarding, people would not be working with so much effort.”

Odds are high that food is one of your favorite topics. Office conversations about where to go for lunch. Calls home on your commute asking what’s for dinner. Recounting a delicious meal in meticulous detail to a friend. Binging on the Food Network. And, of course, your Instagram feed (no pun intended). Food is a near and dear topic for Samuel Yamashita, too. The Pomona College Henry E. Sheffield Professor of History combined two great loves—food and, of course, history—and wrote Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine: The Food Movement That Changed the Way Hawai‘i Eats. In the book, Yamashita chronicles the way Hawaiians have eaten over time, and the way good, local island eats combined with French and Continental mainland fare to create a distinctive style of cuisine.

Odds are high that food is one of your favorite topics. Office conversations about where to go for lunch. Calls home on your commute asking what’s for dinner. Recounting a delicious meal in meticulous detail to a friend. Binging on the Food Network. And, of course, your Instagram feed (no pun intended). Food is a near and dear topic for Samuel Yamashita, too. The Pomona College Henry E. Sheffield Professor of History combined two great loves—food and, of course, history—and wrote Hawai‘i Regional Cuisine: The Food Movement That Changed the Way Hawai‘i Eats. In the book, Yamashita chronicles the way Hawaiians have eaten over time, and the way good, local island eats combined with French and Continental mainland fare to create a distinctive style of cuisine.

Gwendolyn Lytle, who led a distinguished career as a vocal soloist and college professor at the University of California Riverside and Pomona College, passed away on August 22 in Claremont, Calif., after a courageous battle with liver cancer. She was 74. Beloved sister, aunt, colleague, teacher, and friend, her life was dedicated to family and education. Her musical performances included operatic roles, art songs and, her specialty, Negro spirituals.

Gwendolyn Lytle, who led a distinguished career as a vocal soloist and college professor at the University of California Riverside and Pomona College, passed away on August 22 in Claremont, Calif., after a courageous battle with liver cancer. She was 74. Beloved sister, aunt, colleague, teacher, and friend, her life was dedicated to family and education. Her musical performances included operatic roles, art songs and, her specialty, Negro spirituals.