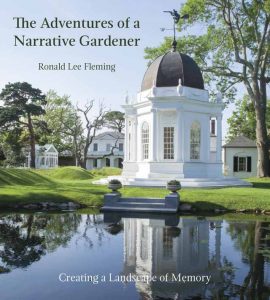

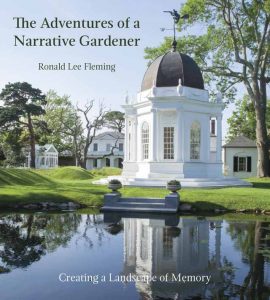

In his career, Ronald Lee Fleming ’63, P’04, author of the newly published The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener: Creating a Landscape of Memory, worked hard as an urban planner, preservationist and innovator, doing Main Street revitalization projects in small towns even before the National Trust for Historic Preservation took them on. In fact, Fleming says, he was once told, “Well, we’ve copied everything you ever did.”

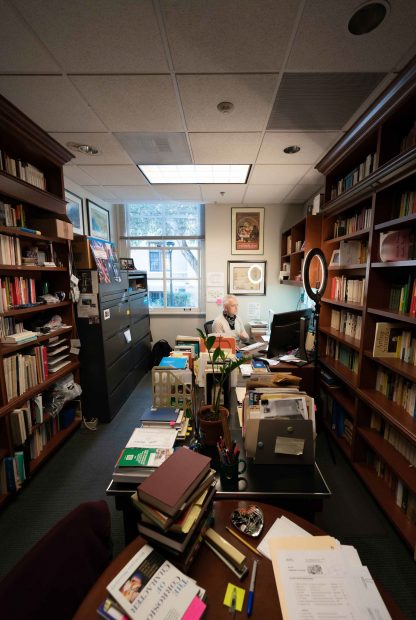

In his career, Ronald Lee Fleming ’63, P’04, author of the newly published The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener: Creating a Landscape of Memory, worked hard as an urban planner, preservationist and innovator, doing Main Street revitalization projects in small towns even before the National Trust for Historic Preservation took them on. In fact, Fleming says, he was once told, “Well, we’ve copied everything you ever did.”

His idea of place-making wasn’t just for Main Street, though; it also extended to home sweet home, in the form of gardens. In the book, Fleming tells the story of his life, his family and friends, his 12 gardens and the gardens that inspire him. In this conversation with Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham, he talks about why he wrote the book and, among other things, offers advice for horticulturalists who also want to be place-makers.

This interview has been condensed and edited for space and clarity.

PCM: How did you first get involved in urban planning?

Fleming: I didn’t know before college that there was such a field as planning. But I had built a little town in my backyard when I was growing up. I went to all the ghost towns in the West, and then I came back and built a little town. I called it the Ghost Town. And that’s what got me involved with all the local neighborhood kids. I was a sort of Tom Sawyer, and they were painting my fence.

Then one summer just after Pomona, I won a fellowship to Deerfield, Massachusetts, where I studied history and decorative arts at Historic Deerfield. You had to write a thesis, so I studied towns. I did a comparative study of Greenfield and Deerfield.

And while I was there, I went up to see Professor Philip Gray’s family who summered on Caspian Lake in Vermont. Peggy Gray motored us in her ancient Pierce Arrow to this little town nearby called Craftsbury Common, which is very beautiful. And I went to a wonderful picnic with all kinds of people of all backgrounds, but they’re all enjoying each other. It was called a Strawberry Supper.

Years later, when I came back from Vietnam, a cynical reporter said to me, “What do you think you were dying for in Vietnam?” I said, “Well, I was dying for a Strawberry Supper on Craftsbury Common.” That was a place where America came together. It was the idea of a common where people of various backgrounds and incomes all came together in harmony.

I still didn’t know there was such a thing as getting a planning degree until I met Professor Gray’s son-in-law who was teaching at MIT. He was a professor of planning, and he got me all involved in that. So when I came back to Harvard, I kind of treated that first year back as a sort of sabbatical. And then I went into planning, and that’s where I got my degree. And that’s what my whole story has been about—planning and place-making.

PCM: So what was your reason for writing this book?

Fleming: I think I had two reasons. One was to celebrate the fact that I had been able to create these 12 gardens and tell a narrative story—through a narrative garden. But I also did it for my children, to help them understand my mentality and what I was up to. And to tell the world what I valued.

Ironically, I now understand that garden-making is something of an achievement, even though I had done all these other things. I had been a fellow at the U.S. National Committee of the International Council on Monuments and Sites. I had been a fellow of the American Institute of Certified Planners. I had received a number of distinctions in my career.

But I think, really, that people may remember me as a gardener.

But it’s not just a pretty book, as one of the writers who reviewed it has said. It’s also a harrowing memoir of Vietnam. Because I was in Vietnam as an intelligence officer assigned to the Special Forces—the Green Berets. And then I was working in the embassy for a while. And then I worked for what we call “the Company.” You know, you can figure that out. All of that is in the book, in Chapter 4, which is the one that is about Vietnam. It’s also about my friends who died. So many of my friends died. So why did I write it? I wrote it to make more precious the memory of these people. And then I also had to talk about the commons, where we could all meet in the back of the garden.

PCM: What is a narrative garden?

Fleming: A narrative garden tells a story. It tells a story about a place. So what I wanted to do was to use the 12 different gardens here at Bellevue House, in Newport, Rhode Island. It’s three and a half acres with a wall around it, so it’s very private, but it’s right next to the downtown. That’s the marvelous thing about it—it’s so urban. I can walk to the club, I can walk to the art museum, I can walk to the Redwood Library, America’s first athenaeum. They’re all within a half-mile. That’s wonderful. Because I’m at the cusp of the residencial part of Bellevue Avenue where the great mansions are located. Have you ever been to Newport?

PCM: No, I haven’t.

Fleming: Newport was this great playground for America’s wealthy people in the Gilded Age. We’re living in a new Gilded Age right now, but that was a time of enormous wealth in America, after the Civil War. Before that time, it was a place of artists, and it was a place of Southerners. Southerners came up in the summertime, and they had houses here. Some of the leading families of Charleston and Savannah had houses right here, including the George Noble Jones family of Savannah who lived across Bellevue Avenue and the Middletons of Charleston who owned my land.

So first, it was a place where Southerners and Northerners got together. After that, it became an artistic retreat, and it became very wealthy. And it became, intellectually, a very powerful place. You had a whole amount of energy here, intellectual and artistic energy. Which created this district of great houses, which I’m still fighting to save on the local level. Trying to save the houses and the character of the place.

PCM: A narrative garden also tells the story of a person. In this case, you. What is it in your life that inspired you to build these gardens?

Fleming: I’ve had an extraordinary life experience. As you know, I worked hard as a planner and innovator. I did all these Main Street projects in small cities and towns. I’ve seen lots of gardens. I survived all kinds of misadventures depicted in the cascade of the years of living dangerously, all the different adventures I’ve had where I was almost killed. I almost skidded off a cliff in a Volkswagen on the edge of the Adriatic Sea 300 feet below. I survived Vietnam, where a sniper missed me by three inches. And you know, and I was almost killed by a village mob near Casablanca, when I was driving my XKE at night and they thought I had clipped a bicyclist, a Third World death sentence. I had a minute to show what happened. Later in life, I had three strokes and a kidney transplant, so with immune deficiencies, I’ve used up my nine lives and am living on borrowed time.

And so even though I’ve had years of some tranquility, all these things inspired the idea of a narrative garden that would tell the story and would relate to all these different gardens that I had seen.

PCM: You write that programming a garden can invoke a spirit. Can you give an example?

Fleming: There’s a muscle memory that comes out of animating a garden space and doing activities in the garden. So the idea of constantly using the garden imprints on the mind the nature of the spirit of the place. I had 35 artists and artisans involved in this thing. So, I was very interested in how you involve the arts and how you make it special. And I didn’t want just the arts to be the single use zoning that we have now in cultural districts in America, where you have an art park and all the artists plopped around on the park. I’m interested in place-making, not plop art. I wanted to have the art relate to the spirit of the place.

PCM: You’ve written—I’m quoting—“Before attempting to transform the built environment, we need training in how to make visual choices and how to understand the visual language.” How do we get that kind of training?

Fleming: I think it’s hard. For instance, I think the visual environment at Pomona has not evolved so well because Pomona has made a lot of mistakes in terms of building choices. Some of the earlier architecture, site plans and buildings by Myron Hunt and Sumner Spalding were beautiful, but they haven’t respected that architecture in terms of a lot of the changes that were made. Until Robert Stern came around, that is—the new student union is quite successful in terms of relating to that vocabulary, so that was a really good choice. I think some of the other choices were not as good, and I’ve told the president about that from time to time.

PCM: You also said you’ve made some mistakes along the way.

Fleming: Yeah, I’ve made mistakes. My biggest mistake is this one garden, which is at the back of the property. What I liked about it was the plane of water and then the diagonal edge—a crisp line—and then beveled grass going up to a tempietto. So my failure was working with landscape architects with no cultural memory. Most people who are living in our age do not have the historical context —they haven’t seen it. I was away when they installed the rocks. And they put in little stones—kind of rough stones, rusticated stones—rather than understanding that what they should have done is a crisp wall edge. I’ve been to Studley Royal in Yorkshire, which is the model for my own garden folly.

PCM: What would be your advice for people building their own gardens?

Fleming: A garden should empower a person. In other words, what I’m trying to do with a narrative garden is to show that other people can tell stories in their gardens. And everybody has a story to tell. And I think our lives are richer if we can tell a story. I want to go beyond the abstraction of just doing drifts of flowers and things like that. I want to empower people to put more meaning into their places. It’s about place-making; it’s about layers of meaning in your life and for your family. And so that’s what I hope we have achieved.

PCM: When you were a student at Pomona, was there a space that you particularly loved?

Fleming: Yes, there was. In fact, that’s where I kissed my first girl. I was a late bloomer. And there was a little courtyard, Lyon Court, next to Little Bridges. That little area there. That bench in the back, that’s where I kissed my first girlfriend.

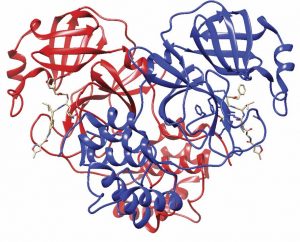

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX.

Understanding how to stop the novel coronavirus from attacking cells and the immune system is a challenge that scientists around the world are facing as they race against the clock to create treatments and vaccines to fight the pandemic. According to new research from Pomona College, Caltech and DePaul University, one key to unlocking that puzzle may have been found in the effect of metal ions on a pair of the novel coronavirus’s proteins—the virus’s main protease, known as 6LU7, and the protein in the virus’s spikes, known as 6VXX. Timing truly is everything, and the children’s book Outside In, by Deborah Underwood ’83, is arguably prescient. Released in April during a pandemic she never anticipated when she wrote the book, it is a vivid meditation on how nature affects us even when we’re stuck indoors. In these strange times of sheltering in place, this book, illustrated by Cindy Derby, gives readers pause to ponder our connectedness to creation.

Timing truly is everything, and the children’s book Outside In, by Deborah Underwood ’83, is arguably prescient. Released in April during a pandemic she never anticipated when she wrote the book, it is a vivid meditation on how nature affects us even when we’re stuck indoors. In these strange times of sheltering in place, this book, illustrated by Cindy Derby, gives readers pause to ponder our connectedness to creation.

1. Grow up in Paradise. Before it was largely destroyed by the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in state history, Paradise, California, was a town steeped in the yo-yo culture of nearby Chico, home of the National Yo-Yo Museum.

1. Grow up in Paradise. Before it was largely destroyed by the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in state history, Paradise, California, was a town steeped in the yo-yo culture of nearby Chico, home of the National Yo-Yo Museum. Still, they run.

Still, they run. In his career, Ronald Lee Fleming ’63, P’04, author of the newly published The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener: Creating a Landscape of Memory, worked hard as an urban planner, preservationist and innovator, doing Main Street revitalization projects in small towns even before the National Trust for Historic Preservation took them on. In fact, Fleming says, he was once told, “Well, we’ve copied everything you ever did.”

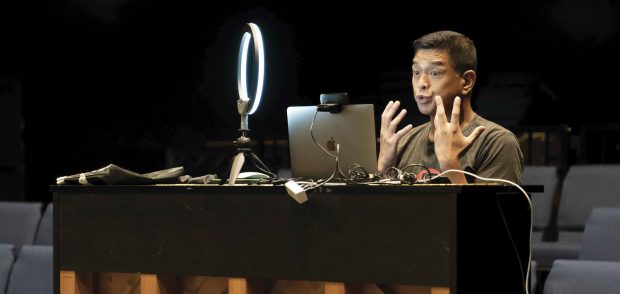

In his career, Ronald Lee Fleming ’63, P’04, author of the newly published The Adventures of a Narrative Gardener: Creating a Landscape of Memory, worked hard as an urban planner, preservationist and innovator, doing Main Street revitalization projects in small towns even before the National Trust for Historic Preservation took them on. In fact, Fleming says, he was once told, “Well, we’ve copied everything you ever did.” In July Pomona College welcomed Nathan Dean ’10 as the new National Chair of Annual Giving. Nathan will serve a two-year term as the College’s primary proponent for annual giving and as an ex-officio member of the Board of Trustees.

In July Pomona College welcomed Nathan Dean ’10 as the new National Chair of Annual Giving. Nathan will serve a two-year term as the College’s primary proponent for annual giving and as an ex-officio member of the Board of Trustees. our new Director of Alumni and Parent Engagement

our new Director of Alumni and Parent Engagement